Personal space

Personal space is the region surrounding a person which they regard as psychologically theirs. Most people value their personal space and feel discomfort, anger, or anxiety when their personal space is encroached.[1] Permitting a person to enter personal space and entering somebody else's personal space are indicators of perception of the relationship between the people. There is an intimate zone reserved for lovers, children and close family members. There is another zone used for conversations with friends, to chat with associates, and in group discussions; a further zone is reserved for strangers, newly formed groups, and new acquaintances; and a fourth zone is used for speeches, lectures, and theater; essentially, public distance is that range reserved for larger audiences.[2]

Entering somebody's personal space is normally an indication of familiarity and at times of intimacy. However, in modern society, especially in crowded urban communities, it is at times difficult to maintain personal space, for example, in a crowded train, elevator or street. Many people find such physical proximity to be psychologically disturbing and uncomfortable,[1] though it is accepted as a fact of modern life. In an impersonal crowded situation, eye contact tends to be avoided. Even in a crowded place, preserving personal space is important, and intimate and sexual contact, such as frotteurism and groping, are normally unacceptable physical contact.

The amygdala is suspected of processing people's strong reactions to personal space violations since these are absent in those in which it is damaged and it is activated when people are physically close.[3]

Size

The notion of personal space was introduced in 1966 by anthropologist Edward T. Hall, who created the concept of proxemics. In his book, The Hidden Dimension, he describes the subjective dimensions that surround each person and the physical distances they try to keep from other people, according to subtle cultural rules. A person's personal space (and the corresponding physical comfort zone) is highly variable and difficult to measure. Estimates for an average Westerner, for example, place it at about 60 centimeters (24 in) on either side, 70 centimeters (28 in) in front and 40 centimeters (16 in) behind.[1]

Personal space is highly variable, and can be due to cultural differences and personal experiences. For example, those living in a densely populated places tend to have a lower expectation of personal space. Residents of India or Japan tend to have a smaller personal space than those in the Mongolian steppe, both in regard to home and individual spaces. Difficulties can be created by failures of intercultural communication due to different expectations of personal space.[1] For a more detailed example, see Body contact and personal space in the United States.

In European culture, personal space has changed historically since Roman times, together with the boundaries of public and private space. This topic has been explored in A History of Private Life (2001), under the general editorship of Philippe Ariès and Georges Duby.[4]

Personal space is also affected by a person's position in society with more affluent individuals expecting a larger personal space.[citation needed]

People make exceptions to, and modify their space requirements. A number of relationships may allow for personal space to be modified and these include familial ties, romantic partners, friendships and close acquaintances where a greater degree of trust and knowledge of a person allows personal space to be modified. In addition, under certain circumstances, when normal space requirements simply cannot be met, such as in public transit or elevators, personal space requirements are modified accordingly.

Adaptation

According to the psychologist Robert Sommer a method of dealing with violated personal space is dehumanization. He argues that (for example) on the subway, crowded people often imagine those intruding on their personal space as inanimate. Behavior is another method: a person attempting to talk to someone can often cause situations where one person steps forward to enter what they perceive as a conversational distance, and the person they are talking to can step back to restore their personal space.[citation needed]

Interpersonal space

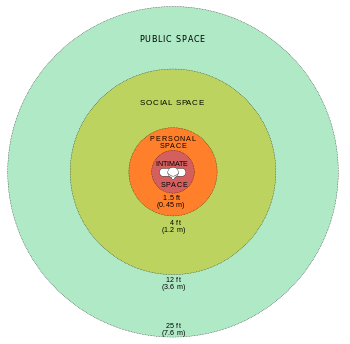

Interpersonal space is the psychological "bubble" that exists when one person stands too close to another. Research has revealed that there are four different zones of interpersonal space:

- Intimate distance ranges from touching to about 18 inches (46 cm) apart, and is reserved for lovers, children, close family members, friends, and pet animals.

- Personal distance begins about an arm's length away; starting around 18 inches (46 cm) from the person and ending about 4 feet (122 cm) away. This space is used in conversations with friends, to chat with associates, and in group discussions.

- Social distance ranges from 4 to 8 feet (1.2 m - 2.4 m) away from the person and is reserved for strangers, newly formed groups, and new acquaintances.

- Public distance includes anything more than 8 feet (2.4 m) away, and is used for speeches, lectures, and theater. Public distance is essentially that range reserved for larger audiences.[5]

Neuropsychological space

Neuropsychology describes personal space in terms of the kinds of 'near-ness' to the body.

- Extrapersonal Space: The space that occurs outside the reach of an individual.

- Peripersonal Space: The space within reach of any limb of an individual. Thus to be 'within-arm's length' is to be within one's peripersonal space.

- Pericutaneous Space: The space just outside our bodies but which might be near to touching it. Visual-tactile perceptive fields overlap in processing this space so that, for example, an individual might see a feather as not touching their skin but still feel the inklings of being tickled when it hovers just above their hand.[6]

Previc[7] further subdivides extrapersonal space into focal-extrapersonal space, action-extrapersonal space, and ambient-extrapersonal space. Focal-extrapersonal space is located in the lateral temporo-frontal pathways at the center of our vision, is retinotopically centered and tied to the position of our eyes, and is involved in object search and recognition. Action-extrapersonal-space is located in the medial temporo-frontal pathways, spans the entire space, and is head-centered and involved in orientation and locomotion in topographical space. Action-extrapersonal space provides the "presence" of our world. Ambient-extrapersonal space initially courses through the peripheral parieto-occipital visual pathways before joining up with vestibular and other body senses to control posture and orientation in earth-fixed/gravitational space. Numerous studies involving peripersonal and extrapersonal neglect have shown that peripersonal space is located dorsally in the parietal lobe whereas extrapersonal space is housed ventrally in the temporal lobe.

Amygdala

Research links the amygdala with emotional reactions to proximity to other people. First, it is activated by such proximity, and second, in those with complete bilateral damage to their amygdala lack a sense of personal space boundary.[3] As the researchers have noted: "Our findings suggest that the amygdala may mediate the repulsive force that helps to maintain a minimum distance between people. Further, our findings are consistent with those in monkeys with bilateral amygdala lesions, who stay within closer proximity to other monkeys or people, an effect we suggest arises from the absence of strong emotional responses to personal space violation."[3]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hall, Edward T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-08476-5.

- ↑ Engleberg, Isa N. Working in Groups: Communication Principles and Strategies. My Communication Kit Series, 2006. page 140-141

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kennedy DP, Gläscher J, Tyszka JM, Adolphs R. (2009). Personal space regulation by the human amygdala. Nat Neurosci. 12:1226-1227. PMID 19718035 doi:10.1038/nn.2381

- ↑ Histoire de la vie privée (2001), editors Philippe Ariès and Georges Duby; le Grand livre du mois. ISBN 978-2020364171. Published in English as A History of Private Life by the Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674399747.

- ↑ Engleberg,Isa N. Working in Groups: Communication Principles and Strategies. My Communication Kit Series, 2006. page 140-141

- ↑ Elias, L.J., M.S., Saucier, (2006) Neuropsychology: Clinical and Experimental Foundations. Boston; MA. Pearson Education Inc. ISBN 0-205-34361-9

- ↑ Previc, F.H. (1998). The neuropsychology of 3D space. Psychol. Bull. 124:123-164.