Perkerra River

| Perkerra River | |

|---|---|

| |

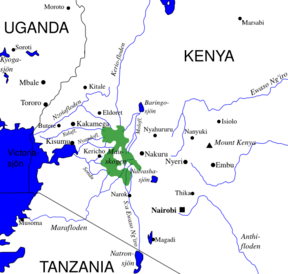

Mau Forest (center, green). Perkerra is the western river flowing from the forest to Lake Baringo to the northeast. Molo River is the eastern river. | |

| Mouth | 0°32′05″N 36°05′33″E / 0.534632°N 36.092491°ECoordinates: 0°32′05″N 36°05′33″E / 0.534632°N 36.092491°E |

| Basin countries | Kenya |

| Source elevation | 2,400 metres (7,900 ft) |

| Mouth elevation | 980 metres (3,220 ft) |

| Basin area | 1,207 square kilometres (466 sq mi)[1] |

The Perkerra River is a river in the Great Rift Valley in Kenya that feeds the freshwater Lake Baringo. It is the only perennial river in the arid and semi-arid lands of the Baringo District.[2] The Perkerra river supplies water to the Perkerra Irrigation Scheme in the Jemps flats near Marigat Township, just south of the lake.[3]

Catchment

The river has a catchment area of 1,207 square kilometres (466 sq mi).[1] It rises in the Mau Forest on the western wall of the Rift valley at 8,000 feet (2,400 m), dropping down to 3,200 feet (980 m) at its mouth on the lake.[4] The catchment area has steep slopes on the hillsides, flattening out lower down.[1] Most of the water comes from the hill slopes, where annual rainfall is from 1,100 millimetres (43 in) to 2,700 millimetres (110 in). The region around the lake is semi-arid, with annual rainfall of 450 millimetres (18 in) and annual evaporation rates of 1,650 millimetres (65 in) to 2,300 millimetres (91 in).[5]

Land use changes

In the late 1800s the alluvial plains near the lake were occupied by the Njemps people, an ethnic group related to the Maasai. They used a brushwood barrier to raise the level of the river and let the water flow over the flat ground. The barrier would be destroyed by the seasonal floods, needing to be replaced, but the system was stable.[6] The British explorer Joseph Thomson visited the Perkerra in the nineteenth century with his caravan and bought grain from the local people, grown using their proven system of irrigation using basins and canals.[7]

With the advent of Europeans in the area, both human and livestick populations increased. The high grass of the catchment was grazed down, erosion increased and run-off rates also increased, causing periodic floods. The brushwood barrier system could not deal with the floods and the Njemps turned to pastoralism. Severe overgrazing, drought and locust invasions led to a food crisis in the late 1920s. In the 1930s the colonial administration began considering the possibility of irrigation, and a formal study was made in 1936, although nothing was done for some years.[8]

Perkerra irrigation scheme

The Perkerra irrigation scheme was launched in 1952 during the Emergency.[3] Construction began in 1954.[9]> Detainees made the roads and prepared the land for irrigation. The project was rushed, expensive to implement and maintain, with little in return. There were difficulties raising crops and difficulty selling them. Many of the tenant farmers who were settled on the project later left. By 1959 it was decided to close the scheme, which had only 100 families, but this was changed to continuing minimal operations. In 1962 the scheme was expanded, and by 1967 there were 500 farming houses, although subsidies were still needed.[3]

The Perkerra irrigation scheme now supports about 670 farm households. Total potential irrigation area is 2,340 hectares (5,800 acres) but only 810 hectares (2,000 acres) has been developed for gravity furrow irrigation and of that 607 hectares (1,500 acres) is being cropped due to a shortage of water. In the past the main crops were onions, chilies, watermelons, pawpaws and cotton. Maize was introduced in 1996 and has proved easier to market.[2] The Kenya Agricultural Research Institute has a research center in Marigat Township that complements the irrigation scheme.[10]

Issues and actions

There is now scarcely any vegetation in the lowlands for eight or nine months of the year apart from swamps in the lower reaches of the Molo and Perkerra rivers and along the lakeshore around their mouths. The swamps, mostly covered by perennial grasses and flooded for only two months of the year, provide grazing for herders.[11] The herders originally had more land, but some has been lost to farmers who immigrated to the area, and some to the irrigation scheme. The herders claim that the irrigation dams have reduced the level of annual floods and thus cut down the amount of pasture.[12]

With little plant cover on most of the lower levels, the soil erodes easily and much sediment is deposited in Lake Baringo. Between 1972 and 2003 the depth of the lake has fallen from 8 metres (26 ft) to 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in).[1] The lake has contracted from 160 square kilometres (62 sq mi) in 1960 to 108 square kilometres (42 sq mi) in 2001. It is becoming saline, and fish stocks are declining. A 2010 study indicated that the river was becoming seasonal. The study recommended implementing a mandatory reserve, or environmental flow. It was thought that the Chemususu dam project on one of the main tributaries of the Perkerra, due to be commissioned in 2011, would mitigate the effect of the reserve on water users while ensuring that the river did not dry up altogether.[13] The dam would hold 11,000,000 cubic metres (390,000,000 cu ft) and will provide 35,000,000 liters (7,700,000 imp gal; 9,200,000 US gal) daily, enough for 200,000 people.[14]

River Water User Associations in the upper regions of the Perkerra and Molo rivers have been planting tree seedlings, protecting the river banks and rehabilitating areas that have become degraded through sand harvesting and quarrying. The Perkerra RWUA has also been protecting springs, a particular concern since 30 out of 72 springs in the area have ceased to flow.[14]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Onyando, Kisoyan & Chemelil 2005, p. 133.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 National Irrigation Board.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Chambers 2005, p. 6.

- ↑ Chambers 1973, p. 345.

- ↑ Akivag et al. 2010, p. 2441-2442.

- ↑ Chambers 1973, p. 345-346.

- ↑ de Laet 1994, p. 113.

- ↑ Chambers 1973, p. 346.

- ↑ SoftKenya.

- ↑ Kenya Agricultural Research.

- ↑ Little 1992, p. 22.

- ↑ Little 1992, p. 136.

- ↑ Akivag et al. 2010, p. 2441.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Mau - ICS.

- Sources

- Akivaga, Erick Mugatsia; Otieno, Fred A. O.; Kipkorir, E. C.; Kibiiy, Joel; Shitote, Stanley (4 December 2010). "Impact of introducing reserve flows on abstractive uses in water stressed Catchment in Kenya: Application of WEAP21 model". International Journal of the Physical Sciences 5 (16): 2441–2449.

- Chambers, Robert (1973). "MWEA: An Irrigated Rice Settlement in Kenya". Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- Chambers, Robert (2005). "Learning from project pathology: The case of Perkerra". Ideas For Development. Earthscan. ISBN 1844070883.

- de Laet, Sigfried J. (1994). History of Humanity: The twentieth century. UNESCO. ISBN 9231040839.

- "KARI Perkerra". Kenya Agricultural Research Institute. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- Little, Peter D. (1992). The Elusive Granary: Herder, Farmer, and State in Northern Kenya. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521405521.

- "The Ministry of Water and Irrigation is spearheading the conservation of catchment areas in the Mau". Mau - ICS. March 9, 2010. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- "Perkerra Irrigation Scheme". National Irrigation Board. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- Onyando, J.; Kisoyan, P.; Chemelil, M. (April 2005). "Estimation of Potential Soil Erosion for River Perkerra Catchment in Kenya". Water Resources Management (Springer) 19 (2): 133–143.

- "Irrigation in Kenya". SoftKenya. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||