Pedro Albizu Campos

| Pedro Albizu Campos | |

|---|---|

Pedro Albizu Campos during his years at Harvard University, 1913-1919 | |

| Born |

September 12, 1891[2] Ponce, Puerto Rico |

| Died |

April 21, 1965 (aged 73) San Juan, Puerto Rico |

| Nationality | Puerto Rican |

| Alma mater | University of Vermont, Harvard University |

| Organization | Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

| Religion | Roman Catholic[3][4] |

| Spouse(s) | Laura Meneses |

| Part of a series on the |

| Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

|---|

Flag of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

|

Events and Revolts |

|

Nationalist Leaders

|

Pedro Albizu Campos[note 1] (September 12, 1891[5] – April 21, 1965) was a Puerto Rican attorney and politician, and the leading figure in the Puerto Rican independence movement. Gifted in languages, he spoke six and was the first Puerto Rican to graduate from Harvard Law School; graduating with the highest grade point average in his entire law class, an achievement that earned him the right to give the valedictorian speech at his graduation ceremony. However, animus towards his mixed racial heritage would lead to his professors delaying two of his final exams in order to keep Albizu Campos from graduating on time. During his time at Harvard University he founded the Knights of Columbus, along with other Catholic students.[6] He also became heavily involved in the Irish struggle for independence.[7][8]

Albizu Campos was the president and spokesperson of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party from 1930 until his death in 1965. Because of his oratorical skill, he was hailed as El Maestro (The Teacher). He was imprisoned twenty-six years for attempting to overthrow the United States government in Puerto Rico.

In 1950, he planned and called for armed uprisings in several cities in Puerto Rico on behalf of independence. Afterward he was convicted and imprisoned again. He died in 1965 shortly after his pardon and release from federal prison, some time after suffering a stroke. There is controversy over his medical treatment in prison.

Early life and education

Pedro Albizu Campos was born in the Tenerías sector of Barrio Machuelo Abajo in Ponce, Puerto Rico to Juana Campos, a domestic worker of Spanish, African and Taíno ancestry, on 12 September 1891. His father, Alejandro Albizu Romero, known as "El Vizcaíno,” was a Basque merchant, from a family of Spanish immigrants who had temporarily resided in Venezuela[5][9][10] From an educated family, Albizu was the nephew of the danza composer Juan Morel Campos, and cousin of Puerto Rican educator Dr. Carlos Albizu Miranda. The boy's mother died when he was young and his father did not acknowledge him until he was at Harvard University.[9]

Albizu Campos graduated from Ponce High School,[11] a "public school for the city's white elite."[9] In 1912, Albizu was awarded a scholarship to study Engineering, specializing in Chemistry, at the University of Vermont. In 1913, he transferred to Harvard University so as to continue his studies.

At the outbreak of World War I, Albizu Campos volunteered in the United States Infantry. Albizu was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Army Reserves and sent to the City of Ponce, where he organized the town's Home Guard. He was called to serve in the regular Army and sent to Camp Las Casas for further training. Upon completing the training, he was assigned to the 375th Infantry Regiment. The United States Army, then segregated, assigned Puerto Ricans of recognizably African descent as soldiers to the all-black units, such as the 375th Regiment. Officers were men classified as white, as was Albizu Campos.

Albizu was honorably discharged from the Army in 1919, with the rank of First Lieutenant. During his military service, he was exposed to the racism of the day. This altered his perspective on U.S.- Puerto Rico relations, and he became the leading advocate for Puerto Rican independence.[12]

In 1919, Albizu returned to his studies at Harvard University, where he was elected president of the Harvard Cosmopolitan Club. He met with foreign students and world leaders, such as Subhas Chandra Bose, the Indian Nationalist leader, and the Hindu poet Rabindranath Tagore. He became interested in the cause of Indian independence and also helped to establish several centers in Boston for Irish independence. Through this work, Albizu Campos met the Irish leader Éamon de Valera and later became a consultant in the drafting of the constitution of the Irish Free State.[13][14]

Albizu graduated from Harvard Law School in 1921 while simultaneously studying Literature, Philosophy, Chemical Engineering, and Military Science at Harvard College. He was fluent in six modern and two classical languages: English, Spanish, French, German, Portuguese, Italian, Latin, and ancient Greek.

Upon graduation from law school, Albizu Campos was recruited for prestigious positions, including a law clerkship to the U.S. Supreme Court, a diplomatic post with the U.S. State Department, the regional vice-presidency (Caribbean region) of a U.S. agricultural syndicate, and a tenured faculty appointment to the University of Puerto Rico.[15]

On June 23, 1921, after graduating from Harvard Law School, Albizu returned to Puerto Rico—but without his law diploma. He had been the victim of racial discrimination by one of his professors. He delayed Albizu Campos' third-year final exams for courses in Evidence and Corporations. Albizu was about to graduate with the highest grade-point average in his entire law school class. As such, he was scheduled to give the valedictory speech during the graduation ceremonies. His professor delayed his exams so that he could not complete his work, and avoided the "embarrassment" of a Puerto Rican law valedictorian.[16]

Albizu Campos left the United States, took and passed the required two exams in Puerto Rico, and in June 1922 received his law degree by mail. He passed the bar exam and was admitted to the bar in Puerto Rico on February 11, 1924.[17]

Marriage and family

In 1922, Albizu married Dr. Laura Meneses, a Peruvian biochemist whom he had met at Harvard University.[18] They had four children named Pedro, Laura, Emilia, and Héctor.[19]

Historical context

After nearly four hundred years of colonial domination under the Spanish Empire, Puerto Rico finally received its colonial autonomy in 1898 through a Carta de Autonomía (Charter of Autonomy). This Charter of Autonomy was signed by Spanish Prime Minister Práxedes Mateo Sagasta and ratified by the Spanish Cortes.[20]

Despite this, just a few months later, the United States claimed ownership of the island as part of the Treaty of Paris, which concluded the Spanish-American War. Persons opposed to the takeover over the years joined together in what became the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. Their position was that, as a matter of international law, the Treaty of Paris could not empower the Spanish to "give" to the United States what was no longer theirs.[21]

Several years after leaving Puerto Rico, in 1913 Charles Herbert Allen, the former first civilian U.S. governor of the island, became president of the American Sugar Refining Company,[22] the largest of its kind in the world. In 1915, he resigned to reduce his responsibilities, but stayed on the board.[22] This company was later renamed as the Domino Sugar company. According to historian Federico Ribes Tovar, Charles Allen leveraged his governorship of Puerto Rico into a controlling interest over the entire Puerto Rican economy.[23]

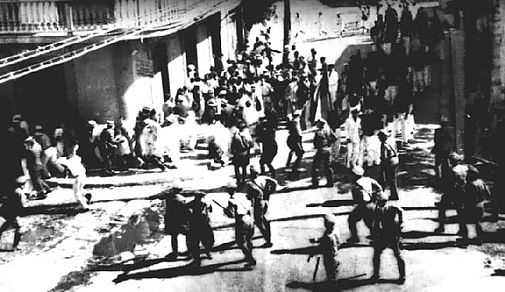

Amid the problems of the Great Depression, the Nationalist movement drew energy from the outrages of the Río Piedras (1935) and the Ponce (1937) massacres. They believed that these showed the extent of violence which the government, supported by the United States, would use to maintain the colonial regime in Puerto Rico.[24] The motive for the violence, especially during the Great Depression, was quite simple: the profits generated by this colonial arrangement were enormous.[24][25]

United States expansion in Latin America

In 1912, the Cayumel Banana company, a United States corporation, orchestrated the military invasion of Honduras in order to obtain hundreds of thousands of acres of Honduran land and tax-free export of its entire banana crop.[26]

By 1928, the United Fruit Company, also a United States corporation, owned over 200,000 acres of prime Colombian farmland. In December of that year, its officials put down a labor strike in what was called the Banana Massacre, resulting in the deaths of 1,000 persons, including women and children.[27][28]

By 1930, United Fruit owned over 1,000,000 acres of land in Guatemala, Honduras, Colombia, Panama, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Mexico and Cuba.[26] By 1940, in Honduras alone, United Fruit owned 50 percent of all private land in the entire country.[26]

By 1942, United Fruit owned 75 percent of all private land in Guatemala—plus most of Guatemala's roads, power stations and phone lines, the only Pacific seaport, and every mile of railroad.[29]

The United States government supported all these economic exploits, and provided military "persuasion" whenever necessary.[30] The precedent was set by President Theodore Roosevelt, who led the Rough Riders in the Battle of San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War of 1898, and declared that “It is manifest destiny for a nation to own the islands which border its shores.”[31] and that if “...any South American country misbehaves it should be spanked.”[32]

Puerto Rican Nationalist Party leadership

Nationalist activists wanted independence from foreign banks, absentee plantation owners, and United States colonial rule. Accordingly, they started organizing in Puerto Rico.

In 1919, José Coll y Cuchí, a member of the Union Party of Puerto Rico, took followers with him to form the Nationalist Association of Puerto Rico in San Juan, to work for independence. They gained legislative approval to repatriate the remains of Ramón Emeterio Betances, the Puerto Rican patriot, from Paris, France.

By the 1920s, two other pro-independence organizations had formed on the Island: the Nationalist Youth and the Independence Association of Puerto Rico. The Independence Association was founded by José S. Alegría, Eugenio Font Suárez and Leopoldo Figueroa in 1920. On September 17, 1922, these three political organizations joined forces and formed the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. Coll y Cuchi was elected president and José S. Alegría (father of Ricardo Alegría) vice president.

In 1924, Pedro Albizu Campos joined the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and was elected vice president. In 1927, Albizu Campos traveled to Santo Domingo, Haiti, Cuba, Mexico, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela, seeking support among other Latin Americans for the Puerto Rican Independence movement.

In 1930, Albizu and José Coll y Cuchí, president of the Party, disagreed on how the party should be run. As a result, Coll y Cuchí abandoned the party and, with some of his followers, returned to the Union Party. On May 11, 1930, Albizu Campos was elected president of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. He formed the first Women's Nationalist Committee, in the island municipality of Vieques, Puerto Rico.[33]

After being elected party president, Albizu declared: "I never believed in numbers. Independence will instead be achieved by the intensity of those that devote themselves totally to the Nationalist ideal."[34] Under the slogan, "La Patria es valor y sacrificio" (The Fatherland is valor and sacrifice), a new campaign of national affirmation was carried out. Albizu Campos' vision of sacrifice was integrated with his Catholic faith.[35]

Accusation against Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads

In 1932, Albizu published a letter accusing Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads, an American pathologist with the Rockefeller Institute, of killing Puerto Rican patients in San Juan's Presbyterian Hospital, as part of his medical research. Albizu Campos had been given an unmailed letter by Rhoads addressed to a colleague, found after Rhoads returned to the United States.[36]

Part of what Rhoads wrote, in a letter to his friend which began by complaining about another's job appointment, included the following:

"I can get a damn fine job here and am tempted to take it. It would be ideal except for the Porto Ricans. They are beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere. It makes you sick to inhabit the same island with them. They are even lower than Italians. What the island needs is not public health work but a tidal wave or something to totally exterminate the population. It might then be livable. I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off 8 and transplanting cancer into several more. The latter has not resulted in any fatalities so far... The matter of consideration for the patients' welfare plays no role here - in fact all physicians take delight in the abuse and torture of the unfortunate subjects."[37][38]

Albizu sent copies of the letter to the League of Nations, the Pan American Union, the American Civil Liberties Union, newspapers, embassies, and the Vatican.[39] He also sent copies of the Rhoads letter to the media, and published his own letter in the Porto Rico Progress. He used it as an opportunity to attack United States imperialism, writing:

"The mercantile monopoly is backed by the financial monopoly... The United States have mortgaged the country to their own financial interests. The military intervention destroyed agriculture. It changed the country into a huge sugar plantation..." Albizu Campos accused Rhoads and the United States of trying to exterminate the native population, saying, "Evidently, submissive people coming under the North American empire, under the shadow of its flag, are taken ill and die. The facts confirm absolutely a system of extermination." He went on, "It [the Rockefeller Foundation] has in fact been working out a plan to exterminate our people by inoculating patients unfortunate enough to go to them with virus of incurable diseases such as cancer."[40]

A scandal erupted. Rhoads had already returned to New York.[41] Governor James R. Beverley of Puerto Rico and his attorney general Ramón Quiñones, as well as Puerto Rican medical doctors Morales and Otero appointed thereby, conducted an investigation of the more than 250 cases treated during the period of Rhoads' work at Presbyterian Hospital. The Rockefeller Foundation also conducted their own investigation.[36] Rhoads said he had written the letter in anger after he found his car vandalized, and it was intended "as a joke" in private with his colleague.[39] An investigation concluded that he had conducted his research and treatment of Puerto Ricans appropriately. When the matter was revisited in 2002, again no evidence was found of medical mistreatment. The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) considered the letter offensive enough to remove Rhoads' name from a prize established to honor his lifelong work in cancer research.[39]

Early Nationalist efforts

The Nationalist movement was intensified by some of its members being killed by police during unrest at the University of Puerto Rico in 1935, in what was called the Río Piedras Massacre. The police were commanded by Colonel E. Francis Riggs, a former United States Army officer. Albizu withdrew the Nationalist Party from electoral politics, saying they would not participate until the United States ended colonial rule.

In 1936, Hiram Rosado and Elías Beauchamp, two members of the Cadets of the Republic, the Nationalist youth organization, assassinated Colonel Riggs. After their arrest, they were killed without a trial at police headquarters in San Juan.[42]

Other police killed marchers and bystanders at a parade in the Ponce Massacre (1936). The Nationalists believed these showed the violence which the United States was prepared to use in order to maintain its colonial regime in Puerto Rico.[24] Historians Manuel Maldonado-Denis and César Ayala believe the motive for this repression, especially during the Great Depression, was because United States business interests were earning such enormous profits by this colonial arrangement.[24][25]

After these events, on April 3, 1936, a federal Grand Jury submitted an indictment against Albizu Campos, Juan Antonio Corretjer, Luis F. Velázquez, Clemente Soto Vélez and the following members of the cadets: Erasmo Velázquez, Julio H. Velázquez, Rafael Ortiz Pacheco, Juan Gallardo Santiago, and Pablo Rosado Ortiz. They were charged with sedition and other violations of Title 18 of the United States Code.[43]

The prosecution based some of their charges on the Nationalists' creation and organization of the Cadets, which the government referred to as the "Liberating Army of Puerto Rico". The prosecutors said that the military tactics which the cadets were taught were for the purpose of overthrowing the Government of the United States.[44][45] A jury of seven Puerto Ricans and five Americans acquitted the individuals by a vote of 7-to-5.

However, Judge Robert A. Cooper did not approve of this verdict. He called for a new trial and a new jury, which was composed of ten Americans and two Puerto Ricans. This second jury concluded that the defendants were guilty.[46]

In 1937, a group of lawyers, including a young Gilberto Concepción de Gracia, appealed the case, but the Boston Court of Appeals, which held appellate jurisdiction, upheld the verdict. Albizu Campos and the other Nationalist leaders were sentenced to the Federal penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia.

In 1939, United States Congressman Vito Marcantonio strongly criticized the proceedings, calling the trial a "frame-up" and "one of the blackest pages in the history of American jurisprudence." [47] In his speech Five Years of Tyranny, Congressman Marcantonio said that Albizu's jury had been profoundly prejudiced since it had been hand-picked by the prosecuting attorney Cecil Snyder. According to Marcantonio, the jury consisted of people "...who had expressed publicly bias and hatred for the defendants."[48] He said Snyder had been told that "the Department of Justice would back him until he did get a conviction."[48]

Marcantonio argued for Puerto Rican rights, saying "As long as Puerto Rico remains part of the United States, Puerto Rico must have the same freedom, the same civil liberties, and the same justice which our forefathers laid down for us. Only a complete and immediate unconditional pardon will, in a very small measure, right this historical wrong."[48]

In 1943, Albizu Campos became seriously ill and had to be interned at the Columbus Hospital of New York. He stayed there until nearly the end of his sentence. In 1947, after ten years of imprisonment, Albizu was released; he returned to Puerto Rico. Within a short period of time, he began preparing for an armed struggle against the United States' plan to turn Puerto Rico into a "commonwealth" of the United States.

Passage of Law 53

In 1948, the Puerto Rican Senate passed Law 53, also called the Ley de la Mordaza (Gag Law). At the time, members of the Partido Popular Democrático (Popular Democratic Party), or PPD, occupied almost all the Senate seats, and Luis Muñoz Marín presided over the chamber.[49]

The bill was signed into law on June 10, 1948, by the United States-appointed governor of Puerto Rico Jesús T. Piñero. It closely resembled the anti-communist Smith Law passed in the United States.[50]

The law made it illegal to own or display a Puerto Rican flag anywhere, even in one's own home. It limited speech against the United States government or in favor of Puerto Rican independence and prohibited one to print, publish, sell or exhibit any material intended to paralyze or destroy the insular government or to organize any society, group or assembly of people with a similar destructive intent. Anyone accused and found guilty of disobeying the law could be sentenced to ten years imprisonment, a fine of $10,000 dollars (US), or both.

Dr. Leopoldo Figueroa, then a member of the Partido Estadista Puertorriqueño (Puerto Rican Statehood Party) and the only non-PPD member of the Puerto Rico House of Representatives, spoke out against the law, saying that it was repressive and in direct violation of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, which guarantees Freedom of Speech.[51] Figueroa noted that since Puerto Ricans had been granted United States citizenship they were covered by its constitutional protections.[51][52]

Second arrest

Pedro Albizu Campos was jailed again after the October 30, 1950 Nationalist revolts, known as the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s, in various Puerto Rican cities and towns against United States rule. Among the more notable of the revolts was the Jayuya Uprising, where a group of Puerto Rican Nationalists, under the leadership of Blanca Canales, held the town of Jayuya for three days; the Utuado Uprising which culminated in what is known as the "Utuado Massacre"; and the attack on La Fortaleza (the Puerto Rican governor's mansion) during the Nationalist attack of San Juan.

On October 31, police officers and National Guardsmen surrounded Salón Boricua, a barbershop in Santurce. Believing that a group of Nationalists were inside the shop, they opened fire. The only person in the shop was Albizu Campos' personal barber, Vidal Santiago Díaz. Santiago Díaz fought alone against the attackers for three hours and received five bullet wounds, including one in the head. The entire gunfight was transmitted "live" via the radio airwaves, and was heard all over the island. Overnight Santiago Díaz, the courageous barber who survived an armed attack by forty police and National Guardsmen, became a legend throughout Puerto Rico.[53]

During the revolt, Albizu was at the Nationalist Party’s headquarters in Old San Juan, which also served as his residence. That day he was accompanied by Juan José Muñoz Matos, Doris Torresola Roura (cousin of Blanca Canales and sister of Griselio Torresola), and Carmen María Pérez Roque. The occupants of the building were surrounded by the police and the National Guard who, without warning, fired their weapons. Doris Torresola, who was shot and wounded, was carried out during a ceasefire by Muñoz Matos and Pérez Roque. Alvaro Rivera Walker, a friend of Pedro Albizu Campos, somehow made his way to the Nationalist leader. He stayed with Albizu Campos until the next day when they were attacked with gas. Rivera Walker then raised a white towel he attached to a pole and surrendered. All the Nationalists, including Albizu, were arrested.[54]

On November 1, 1950, Nationalists Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola attacked Blair House in Washington, D.C. where president Harry S. Truman was staying while the White House was being renovated. During the attack on the president, Torresola and a policeman, Private Leslie Coffelt, were killed.

Because of this assassination attempt, Pedro Albizu Campos was immediately attacked at his home. After a shootout with the police, Albizu Campos was arrested and sentenced to eighty years in prison. Over the next few days, 3,000 independence supporters were arrested all over the island.

Albizu was pardoned in 1953 by then-governor Luis Muñoz Marín but the pardon was revoked the following year after the 1954 nationalist attack of the United States House of Representatives, when four Puerto Rican Nationalists, led by Lolita Lebrón, opened fire from the gallery of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C..

Though in ill health, Pedro Albizu Campos was arrested at once when Lolita Lebrón, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Andrés Figueroa Cordero, and Irving Flores, unfurled a Puerto Rican flag and opened fire on March 1, 1954 on the members of the 83rd Congress with the intention of capturing world-wide attention to the cause of Puerto Rican independence .[55] Ruth Mary Reynolds, the American Nationalist, went to the defense of Albizu Campos and the four Nationalists involved in the shooting incident with the aid of the American League for Puerto Rico's Independence.[56]

Later years and death

During his imprisonment, Albizu suffered deteriorating health.[57] He alleged that he was the subject of human radiation experiments in prison and said that he could see colored rays bombarding him. When he wrapped wet towels around his head in order to shield himself from the radiation, the prison guards ridiculed him as El Rey de las Toallas (The King of the Towels).[58]

Officials suggested that Pedro Albizu Campos was suffering from mental illness, but other prisoners at La Princesa prison including Francisco Matos Paoli, Roberto Díaz and Juan Jaca, claimed that they felt the effects of radiation on their own bodies as well.[59][60]

Dr. Orlando Daumy, a radiologist and president of the Cuban Cancer Association, traveled to Puerto Rico to examine him. From his direct physical examination of Albizu Campos, Dr. Daumy reached three specific conclusions:

- 1) that the sores on Albizu Campos were produced by radiation burns

- 2) that his symptoms corresponded to those of a person who had received intense radiation,

- 3) that wrapping himself in wet towels was the best way to diminish the intensity of the rays.[61]

In 1956, Albizu suffered a stroke in prison and was transferred to San Juan's Presbyterian Hospital under police guard.

On November 15, 1964, on the brink of death, Pedro Albizu Campos was pardoned by Governor Luis Muñoz Marín. He died on April 21, 1965.

More than 75,000 Puerto Ricans were part of a procession that accompanied his body for burial in the Old San Juan Cemetery.[62]

Later events

In December 1993, the United States Secretary of Energy, Hazel O'Leary, disclosed that about 800 radiation tests were conducted on humans by the Federal nuclear energy program during the 1950s and 1960s. These human experiments included at least 319 hospital patients, employees and prison convicts. The human experiments were supported by the Atomic Energy Commission, NASA and the Public Health Service.[63]

In 1994, under the administration of President Bill Clinton, the United States Department of Energy disclosed that numerous human radiation experiments had been conducted on behalf of the government from the 1950s through the 1970s.[64]

Victor Villanueva, a professor in English at Washington State University, wrote in 2009 that Albizu Campos had repeatedly said that he was being subjected to radiation in prison. Villanueva also researched and confirmed the U.S. Department of Energy disclosure of radiation experiments.[65]FBI files on Albizu Campos

In the 2000s, researchers got files from the FBI released under the Freedom of Information Act, revealing that the San Juan FBI office had coordinated with FBI offices in New York, Chicago and other cities, in a decades-long surveillance of Albizu and Puerto Ricans who had contact or communication with him. These documents are viewable online, including some as recent as 1965.[66][67]

Legacy

Pedro Albizu Campos' legacy is the subject of discussion among supporters and detractors. His followers state that Albizu's political and military actions served as a primer for positive change in Puerto Rico, these being:

- the improvement of labor conditions for peasants and workers;

- a more accurate assessment of the colonial relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States;

- an awareness by the political establishment in Washington, D.C. of this colonial relationship.

Pedro Albizu Campos can definitely be credited with preserving and promoting Puerto Rican Nationalism and national symbols at a time where they were virtually taboo in the country—and even actively outlawed by Law 53. The formal adoption of the Puerto Rican flag as a national emblem by the Puerto Rican government can be traced to Albizu Campos. The revival of public observance of the Grito de Lares and its significant icons was a direct mandate from him as leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party.

Honors

|

| |

|

|

- In Chicago, an alternative high school is named the Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School.

- In New York City, Public School 161 in Harlem is named after him[citation needed].

- In Puerto Rico, five public schools are named after him[citation needed].

- In Puerto Rico, there are streets in most municipalities named after him[citation needed].

- In Ponce, there is a Pedro Albizu Campos Park and lifesize statue dedicated to his memory. Every September 12, his contributions to Puerto Rico are remembered at this park on the celebration of his birthday.[68]

- In Salinas, there is a "Plaza Monumento Don Pedro Albizu Campos", a plaza and 9-foot statue dedicated to his memory. It was dedicated on January 11, 2013, the birth day of Eugenio María de Hostos, another Puerto Rican who struggled for Puerto Rico's independence. Quite unique among Puerto Rican thought, the plaza-monument was erected and dedicated by a municipal government of the opposite (statehood) political ideology as that of Albizu Campos.[69]

- In 1993, Chicago alderman Billy Ocasio, in supporting a statue of Albizu Campos in Humboldt Park, likened him to such American leaders as Patrick Henry, Chief Crazy Horse, John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and W.E.B. Dubois.[70]

See also

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Pedro Albizu Campos |

- Puerto Rican Independence Movement

- Puerto Ricans in World War I

- Puerto Rican Nationalist Party

- Jayuya Uprising

- Utuado Uprising

- San Juan Nationalist revolt

- Puerto Rican Independence Party

- Blanca Canales

Notes

- ↑ This name uses Spanish naming customs; the first or paternal family name is Albizu and the second or maternal family name is Campos.

References

- ↑ (Spanish) "La Masacre de Ponce". Proyecto Salón Hogar. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ↑ Luis Fortuño Janeiro. Album Histórico de Ponce (1692-1963). Page 290. Ponce, Puerto Rico: Imprenta Fortuño. 1963.

- ↑ Stephen Hunter and John Bainbridge, Jr. American Gunfight: The Plot to Kill Harry Truman--and the Shoot-out that Stopped It, (New York: Simon & Schuster. 2007)

- ↑ Juan Manuel Carrión, Teresa C. Gracia Ruiz, La Nación Puertorriqueña: ensayos en torno a Pedro Albizu Campos, p. 145

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Luis Fortuño Janeiro. Album Histórico de Ponce (1692-1963). p. 290. Ponce, Puerto Rico: Imprenta Fortuño. 1963.

- ↑ Marisa Rosado, Pedro Albizu Campos: Las Llamas de la Aurora (San Juan, PR: Ediciones Puerto, Inc., 2008), pp. 56-74.

- ↑ Boston Daily Globe, November 3, 1950.

- ↑ Marisa Rosado, Pedro Albizu Campos: Las Llamas de la Aurora (San Juan, PR: Ediciones Puerto, Inc., 2008), p. 71.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 A. W. Maldonado, Luis Muñoz Marín: Puerto Rico's Democratic Revolution, La Editorial, University of Puerto Rico, 2006, p. 85

- ↑ Federico Ribes Tovar, Albizu Campos" Puerto Rican Revolutionary, p. 17. Note: It says that his father, Alejandro Albizu Romero, known as "El Vizcaíno”, was a Basque merchant living in Ponce. His mother, Julia Campos is described as being of Spanish, Indian (Taíno) and African descent.

- ↑ Puerto Rico's Secret Police/FBI Files on Suspect #4232070, Pedro Albizu Campos., Federal Bureau of Investigation. In, "Freedom of Information - Privacy Acts Section. Office of Public and Congressional Affairs. Subject: Pedro Albizu Campos. File Number 105-11898, Section XIII." Page 38. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Negroni, Héctor Andrés (1992). Historia militar de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario. ISBN 84-7844-138-7. Unknown parameter

|comment=ignored (help) - ↑ Boston Daily Globe, November 3, 1950.

- ↑ Marisa Rosado, Pedro Albizu Campos: Las Llamas de la Aurora (San Juan, PR: Ediciones Puerto, Inc., 2008), p. 71.

- ↑ American Gunfight. Simon and Schuster. 2005. ISBN 0-7432-8195-0. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Juramentación de Pedro Albizu Campos como Abogado: Regreso de Harvard a Puerto Rico", La Voz de la Playa de Ponce, Edición 132, November 2010. Page 7. A reproduction of a segment from the book Las Llamas de la Aurora: Pedro Albizu Campos, un acercamiento a su biografía, by Marisa Rosado (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Ediciones Puerto. 1991.)

- ↑ "Juramentación de Pedro Albizu Campos como Abogado: Regreso de Harvard a Puerto Rico", Periódico La Voz de la Playa de Ponce, November 2010, p. 7

- ↑ "Juramentación de Pedro Albizu Campos como Abogado: Regreso de Harvard a Puerto Rico", Periódico La Voz de la Playa de Ponce, Edición 132, November 2010. Page 7. A reproduction of a segment from the book Las Llamas de la Aurora: Pedro Albizu Campos, un acercamiento a su biografía by Marisa Rosado (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Ediciones Puerto. 1991.)

- ↑ Marisa Rosado, Las Llamas de la Aurora: Pedro Albizu Campos, pp.98-107; Ediciones Puerto, Inc., 2008

- ↑ Ribes Tovar et al., p.106-109

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Ribes Tovar et al., p.122-144

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Charles H. Allen Resigns", New York Times, 16 June 1915, accessed 2 November 2013

- ↑ Federico Ribes Tovar; Albizu Campos: Puerto Rican Revolutionary, pp. 122-144, 197-204; Plus Ultra Publishers, 1971

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Manuel Maldonado-Denis, Puerto Rico: A Socio-Historic Interpretation, pp. 65-83; Random House, 1972

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 César J. Ayala; American Sugar Kingdom, pp.221-227; University of North Carolina Press, 1999

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Rich Cohen; The Fish That Ate the Whale; pub. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2012; pp. 14-67

- ↑ Carrigan, Ana (1993). The Palace of Justice: A Colombian Tragedy. Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 0-941423-82-4. p. 16

- ↑ Bucheli, Marcelo. Bananas and business: The United Fruit Company in Colombia, 1899–2000. p. 132

- ↑ Rich Cohen; The Fish That Ate the Whale; pub. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2012; p. 174.

- ↑ Rich Cohen; The Fish That Ate the Whale; pub. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2012; pp. 75-98, 155-160, 173-212.

- ↑ Perkins, Dexter (1937), The Monroe Doctrine, 1867-1907, Baltimore Press; p. 333

- ↑ Roosevelt, Theodore, Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography; pub. Macmillan Press, 1913; p. 172

- ↑ Rosado, Marisa; Pedro Albizu Campos, pp. 127-188; pub. Ediciones Puerto, Inc., 1992; ISBN 1-933352-62-0

- ↑ Maldonado, A. W. (2004). LMM: Puerto Rico's democratic revolution. La Editorial, UPR. ISBN 0-8477-0158-1.

- ↑ Bridging the Atlantic. SUNY Press. 1996. p. 129. ISBN 0-7914-2917-2. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "DR. RHOADS CLEARED OF PORTO RICO PLOT", New York Times, 15 February 1932

- ↑ Packard, Gabriel. "RIGHTS: Group Strips Racist Scientist's Name from Award", IPS.org, 29 April 2003 21:45:36 GMT

- ↑ Truman R. Clark. 1975. Puerto Rico and the United States, 1917-1933, University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 151-154. This has full text of letter.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Starr, Douglas. "Revisiting a 1930s Scandal: AACR to Rename a Prize", Science, Vol. 300. No. 5619. 25 April 2003, pp. 574-5.

- ↑ “Charge Race Extermination Plot,” Porto Rico Progress, 4 February 1932.

- ↑ Susan E. Lederer, " 'Porto Ricochet': Joking about Germs, Cancer, and Race Extermination in the 1930s", American Literary History, Volume 14. No. 4, Winter 2002, Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Federico Ribes Tovar, Albizu Campos" Puerto Rican Revolutionary, pp. 57-62; Plus Ultra Publishers, Inc., 1972

- ↑ FBI Files on Puerto Ricans

- ↑ "FBI Files"; "Puerto Rico Nationalist Party"; SJ 100-3; Vol. 23; pages 104-134.

- ↑ "Nationalist Insurrection of 1950", Write of Fight

- ↑ Timelines: "The Imprisonment of Men and Women Fighting Colonialism, 1930 - 1940", Puerto Rican Dreams, Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- ↑ Congressional Record, 76th Cong., 1st Sess., 81:10780 Appendix

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Congressional Record, 76th Cong., 1st Sess., 81:10780, (Appendix)

- ↑ Dr. Carmelo Delgado Cintrón, "La obra jurídica del Profesor David M. Helfeld (1948-2008)", Academia Jurisprudencia, Puerto Rico

- ↑ "Puerto Rican History". Welcome to Puerto Rico. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "Para declarar el día 21 de septiembre como el Día del Natalicio de Leopoldo Figueroa Carreras", Lex Juris, LEY NUM. 282 DE 22 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2006, accessed 8 December 2012

- ↑ La Gobernación de Jesús T. Piñero y la Guerra Fría

- ↑ Premio a Jesús Vera Irizarry

- ↑ The Nationalist Insurrection of 1950

- ↑ Carlos "Carlitos" Rovira (March 2012). "Lolita Lebrón, a bold fighter for Puerto Rican independence". S&L Magazine.

- ↑ Guide to the Ruth M. Reynolds Papers 1915-1989

- ↑ Secret files: FBI File on Albizu Campos, Puerto Rico, Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- ↑ Federico Ribes Tovar, Albizu Campos: Puerto Rican Revolutionary, p. 136-139; Plus Ultra Publishers, 1971

- ↑ Rosado, Marisa; Pedro Albizu Campos; pub. Ediciones Puerto, 2008; p. 386. ISBN 1-933352-62-0

- ↑ Torres, Heriberto Marín; Eran Ellos, pub. Ediciones Ciba, 2000; pp. 32-62

- ↑ Federico Ribes Tovar, Albizu Campos: Puerto Rican Revolutionary, Plus Ultra Publishers, 1971; pp. 136-139.

- ↑ "Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos". Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ U.S. Seeks People in Radiation Tests; The New York Times; December 25, 1993. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments", National Security Archives, George Washington University, Retrieved July 26, 2010

- ↑ Victor Villanueva, "Colonial Memory and the Crime of Rhetoric: Pedro Albizu Campos", common reading assignment, Washington State University, American Studies. published in 'College English, Volume 71, Number 6. July 2009. National Council of Teachers of English. (Also appearing as "Colonial Research: A Preamble to a Case Study," in Beyond the Archives: Research as a Lived Process, Gesa Kirsch and Liz Rohan, editors. Southern Illinois University Press, p. 636

- ↑ FBI Files on Pedro Albizu Campos

- ↑ FBI Files on Surveillance of Puerto Ricans in general

- ↑ Rememorarán a Burgos y Albizu en Ponce. Reinaldo Millán. La Perla del Sur. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 11 September 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ Colapsa en acto público Ayoroa Santaliz: inauguración de la Plaza Monumento Pedro Albizu Campos en Salinas. Reinaldo Millán. La Perla del Sur. Ponce, Puerto Rico. Year 31, Issue 1520. Page 14. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ Billy Ocasio, "Campos Deserves Respect-and A Statue", Chicago Tribune, 12 August 1993. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- Acosta, Ivonne, La Mordaza/Puerto Rico 1948-1957. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, 1987

- Connerly, Charles, ed. Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos, Vieques Times, Puerto Rico, 1995

- Corretjer, Juan Antonio, El Líder De La Desesperación, Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, 1978

- Dávila, Arlene M., Sponsored Identities, Cultural Politics in Puerto Rico, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1997

- García, Marvin, Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos, National Louis University

- Torres Santiago, José M., 100 Years of Don Pedro Albizu Campos

External links

- Joan Klein, Oncology Times Interview: "Susan B. Horwitz, PhD, Finishes Term (Plus!!) As AACR President!/Cornelius P. Rhoads Controversy", Oncology Times, 25 July 2003, Vol. 25 - Issue 14, pp. 41–42

- "Pedro Albizu Campos", Portraits of Notable Individuals in the Struggle for Puerto Rican Independence, Peace Host website

- FBI Files on Puerto Rico

- "Human Radiation Experiments", US Department of Energy, 1994

- "Pedro Albizu Campos" Biografias y Vidas

- Habla Albizu Campos, Paredon Records, Smithsonian Institution

- ¿Quién Es Albizu Campos? (Who is Albizu Campos?), Film Documentary website, not in distribution

|