Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage

The Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage (or Peaucellier–Lipkin cell, or Peaucellier–Lipkin Inversor), invented in 1864, was the first planar straight line mechanism -- the first planar linkage capable of transforming rotary motion into perfect straight-line motion, and vice versa. It is named after Charles-Nicolas Peaucellier (1832–1913), a French army officer, and Yom Tov Lipman Lipkin, a Lithuanian Jew and son of the famed Rabbi Israel Salanter.[1][2]

Until this invention, no planar method existed of producing straight motion without reference guideways, making the linkage especially important as a machine component and for manufacturing. In particular, a piston head needs to keep a good seal with the shaft in order to retain the driving (or driven) medium. The Peaucellier linkage was important in the development of the steam engine.

The mathematics of the Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage is directly related to the inversion of a circle.

Earlier Sarrus linkage

There is an earlier straight-line mechanism, whose history is not well known, called Sarrus linkage. This linkage predates the Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage by 11 years and consists of a series of hinged rectangular plates, two of which remain parallel but can be moved normally to each other. Sarrus' linkage is of a three-dimensional class sometimes known as a space crank, unlike the Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage which is a planar mechanism.

Geometry

In the geometric diagram of the apparatus, six bars of fixed length can be seen: OA, OC, AB, BC, CD, DA. The length of OA is equal to the length of OC, and the lengths of AB, BC, CD, and DA are all equal forming a rhombus. Also, point O is fixed. Then, if point B is constrained to move along a circle (shown in red) which passes through O, then point D will necessarily have to move along a straight line (shown in blue). On the other hand, if point B were constrained to move along a line (not passing through O), then point D would necessarily have to move along a circle (passing through O).

Mathematical proof of concept

Collinearity

First, it must be proven that points O, B, D are collinear.

Triangles BAD and BCD are congruent because side BD is congruent to itself, side BA is congruent to side BC, and side AD is congruent to side CD. Therefore angles ABD and CBD are equal.

Next, triangles OBA and OBC are congruent, since sides OA and OC are congruent, side OB is congruent to itself, and sides BA and BC are congruent. Therefore angles OBA and OBC are equal.

- angle OBA + angle ABD + angle DBC + angle CBO = 360°

but angle OBA = angle OBC and angle DBA = angle DBC, thus

- 2 × angle OBA + 2 × angle DBA = 360°

- angle OBA + angle DBA = 180°

therefore points O, B, and D are collinear.

Inverse points

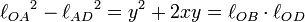

Let point P be the intersection of lines AC and BD. Then, since ABCD is a rhombus, P is the midpoint of both line segments BD and AC. Therefore length BP = length PD.

Triangle BPA is congruent to triangle DPA, because side BP is congruent to side DP, side AP is congruent to itself, and side AB is congruent to side AD. Therefore angle BPA = angle DPA. But since angle BPA + angle DPA = 180°, then 2 × angle BPA = 180°, angle BPA = 90°, and angle DPA = 90°.

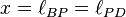

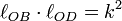

Let:

Then:

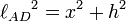

(due to the Pythagorean theorem)

(due to the Pythagorean theorem) (Pythagorean theorem)

(Pythagorean theorem)

Since OA and AD are both fixed lengths, then the product of OB and OD is a constant:

and since points O, B, D are collinear, then D is the inverse of B with respect to the circle (O,k) with center O and radius k.

Inversive geometry

Thus, by the properties of inversive geometry, since the figure traced by point D is the inverse of the figure traced by point B, if B traces a circle passing through the center of inversion O, then D is constrained to trace a straight line. But if B traces a straight line not passing through O, then D must trace an arc of a circle passing through O. Q.E.D.

A typical driver

acts as the driver of the Peaucellier-Lipkin linkage

Peaucellier–Lipkin linkages (PLLs) may have several inversions. A typical example is shown in the opposite figure, in which a rocker-slider four-bar serves as the input driver. To be precise, the slider acts as the input, which in turn drives the right grounded link of the PLL, thus driving the entire PLL.

Historical notes

Sylvester (Collected Works, Vol. 3 Paper 2 ) writes that when he showed a model to Kelvin, he 'nursed it as if it had been his own child, and when a motion was made to relieve him of it, replied "No! I have not had nearly enough of it—it is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen in my life"'.

See also

References

- ↑ "Mathematical tutorial of the Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage". Kmoddl.library.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ↑ Taimina, Daina. "How to draw a straight line by Daina Taimina". Kmoddl.library.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

Bibliography

- Ogilvy CS (1990), Excursions in Geometry, Dover, pp. 46–48, ISBN 0-486-26530-7

- Bryant, John; Sangwin, Chris (2008). How round is your circle? : where engineering and mathematics meet. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 33–38; 60–63. ISBN 978-0-691-13118-4. — proof and discussion of Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage, mathematical and real-world mechanical models

- Coxeter HSM, Greitzer SL (1967). Geometry Revisited. Washington: MAA. pp. 108–111. ISBN 978-0-88385-619-2. (and references cited therein)

- Hartenberg, R.S. & J. Denavit (1964) Kinematic synthesis of linkages, pp 181–5, New York: McGraw-Hill, weblink from Cornell University.

- Johnson RA (1960). Advanced Euclidean Geometry: An elementary treatise on the geometry of the triangle and the circle (reprint of 1929 edition by Houghton Miflin ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 46–51. ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0.

- Wells D (1991). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry. New York: Penguin Books. p. 120. ISBN 0-14-011813-6.

External links

- How to Draw a Straight Line, online video clips of linkages with interactive applets.

- How to Draw a Straight Line, historical discussion of linkage design

- Interactive Java Applet with proof.

- Java animated Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage

- Jewish Encyclopedia article on Lippman Lipkin and his father Israel Salanter

- Peaucellier Apparatus features an interactive applet

- A simulation using the Molecular Workbench software

- A related linkage called Hart's Inversor.

- Modified Peaucellier robotic arm linkage (Vex Team 1508 video)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||