Paulicianism

| Part of a series on |

| Gnosticism |

|---|

|

| History |

|

| Proto-Gnostics |

| Scriptures |

| Related articles |

Paulicians (Armenian: Պաւղիկեաններ, also remembered as Pavghikians/Pavlikians or Paulikianoi[1]) were a Christian Adoptionist sect, also accused by medieval sources of being Gnostic and quasi Manichaean Christian. They flourished between 650 and 872 in Armenia and the Eastern Themes of the Byzantine Empire. According to medieval Byzantine sources, the group's name was derived from the 3rd century Bishop of Antioch, Paul of Samosata.[2][3]

History

The founder of the sect is said to have been an Armenian by the name of Constantine,[4] who hailed from Mananalis, a community near Paytakaran. He studied the Gospels and Epistles, combined dualistic and Christian doctrines, and, upon the basis of the former, vigorously opposed the formalism of the church.

According to Christian historian and scholar Samuel Vila (A las fuentes del cristianismo, p. 203, 5th Ed. 1976, Tell; 1st Ed. 1931): "...allá el año 660, hospedó en su casa a un diácono, quien puso en sus manos un precioso y raro tesoro en aquellos tiempos anteriores a la invención de la imprenta: un Nuevo Testamento. Por su lectura obtuvo el conocimiento de la plena salvación que hay en Cristo; y al comunicar esas buenas nuevas a otras personas formó un grupo de creyentes sinceros; y más tarde, de predicadores ... recibieron el nombre de Paulicianos ..." The above, freely translated as: " ... in the year 660 [ Constantine ] received a deacon in his house, who put in his hands a precious and rare treasure in those days before the invention of the printing press: a New Testament. Upon reading the same he came to know about the whole salvation in Christ; and upon sharing said good news with others, he formed a group of sincere believers; later on, of preachers ... who became known as Paulicians ..."

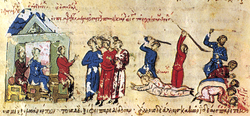

Regarding himself as called to restore the pure Christianity of Paul, he adopted the name Silvanus (one of Paul’s disciples) and about the year 660 founded his first congregation at Kibossa in Armenia. Twenty-seven years afterwards he was stoned to death by order of the emperor.[citation needed] Simeon, the court official who executed the order, was himself converted and, adopting the name Titus, became Constantine’s successor, but was burned to death (the punishment pronounced upon the Manichaeans) in 690.[citation needed]

The adherents of the sect fled, with Paul at their head, to Episparis. He died in 715, leaving two sons, Gegnaesius (whom he had appointed his successor) and Theodore. The latter, giving out that he had received the Holy Ghost, rose up against Gegnaesius, but was unsuccessful. Gegnaesius was taken to Constantinople, appeared before Leo the Isaurian, was declared innocent of heresy, returned to Episparis, but, fearing danger, went with his adherents to Mananalis. His death (in 745) was the occasion of a division in the sect; Zacharias and Joseph being the leaders of the two parties. The latter had the larger following and was succeeded by Baanies, 775. The sect grew in spite of persecution, receiving additions from the iconoclasts.[citation needed] The Paulicians were now divided into the Baanites (the old party), and the Sergites (the reformed sect). Sergius, as the reformed leader, was a zealous and effective converter for his sect; he boasted that he had spread his Gospel "from East to West. from North to South".[5] At the same time the Sergites fought against their rivals and nearly exterminated them.[5]

Baanes was supplanted by Sergius-Tychicus, 801, who was very active for thirty-four years. His activity was the occasion of renewed persecutions on the part of Leo the Armenian. Obliged to flee, Sergius and his followers settled at Argaum, in that part of Armenia which was under the control of the Saracens. At the death of Sergius, the control of the sect was divided between several leaders. The Empress Theodora, as regent to her son Michael III, instituted a new persecution[citation needed], in which a hundred thousand Paulicians in Byzantine Armenia are said to have lost their lives and all of their property and lands were confiscated by the State.[6] Paulicians under their new leader Karbeas, who fled with the residue of the sect, two cities, Amara and Tephrike (modern Divrigi), were built. By 844, at the height of its power, the Paulicians established a "Paulician state" at Tephrike (present-day Divriğ̇, Turkey). In 856 Karbeas and his people took refuge with the Arabs in the territory around Tephrike and joined forces with Umar al-Aqta, emir of Melitene (who reigned 835-863).[7] Karbeas was killed in 863 in Michael III's campaign against the Paulicians, and was possibly with Umar at Malakopea before the battle of Lalakaon.

His successor, Chrysocheres, devastated many cities; in 867 he advanced as far as Ephesus, and took many priests as prisoners.[citation needed] In 868 the Emperor Basil I dispatched Petrus Siculus to arrange for their exchange. His sojourn of nine months among the Paulicians gave him an opportunity to collect many facts, which he preserved in his History of the empty and vain heresy of the Manichæans, otherwise called Paulicians. The propositions of peace were not accepted, the war was renewed, and Chrysocheres was killed at Bathys Ryax. The power of the Paulicians was broken. Meanwhile other Paulicians, sectarians but not rebels, lived in communities throughout the empire. Constantine V had already transferred large numbers of them to Thrace.[8]

In 871, the emperor Basil I ended the power of the "Paulician state" and the survivors fled to Syria and Armenia. In 970, the Paulicians of Syria were transferred by the emperor John Tzimisces to Philippopolis in Thrace and, as a reward for their promise to keep back "the Scythians" (in fact Bulgarians), the emperor granted them religious freedom. This was the beginning of a revival of the sect, but it was true to the empire. Several thousand went in the army of Alexius Comnenus against the Norman Robert Guiscard but, deserting the emperor, many of them (1085) were thrown into prison. By some accounts, Alexius Comnenus is credited with having put an end to the heresy. During a stay at Philippopolis, Alexius argued with the sect, bringing most, if not all, back to the Church (so his daughter: "Alexias", XV, 9). For the converts the new city of Alexiopolis was built, opposite Philippopolis. After this episode, Paulicians as a major force disappear from history, though as a powerless minority they would reappear in many later times and places .[8] When the Crusaders took Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade (1204), they found some Paulicians, whom the historian Gottfried of Villehardouin calls Popelicans.

At the end of the 17th century, the Paulician people around Nicopolis were persecuted by the Ottoman Empire, after the uprising of Chiprovtsi in 1688, and a good part of them fled across the Danube and settled in the Banat region.

There are still over ten thousand Banat Romanians in Banat today, in the villages of Dudeştii Vechi, Vinga, Breştea and also in the city of Timişoara, with a few in Arad; however, they no longer practice their religion, having converted to Roman Catholicism, but their distinctive folk songs and dances are still performed.[9][10] [11] After Bulgaria's liberation from Ottoman rule in 1878, a number of Banat Bulgarians resettled in the northern part of the country and reside there to this day (the villages of Bardarski Geran, Gostilya, Dragomirovo, Bregare and Asenovo. There are also a few villages of Paulicians in the Serbian part of Banat, especially the villages of Ivanovo and Belo Blato, near Pančevo.

In Russia after the war of 1828-29 Paulician communities could still be found in the part of Armenia occupied by the Russians. Documents of their professions of faith and disputations with the Georgian bishop about 1837 (Key of Truth, xxiii-xxviii) were later published by Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare. It is with Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare publications of the Paulicians disputations and "The Key of Truth" that Conybeare based his depiction of the Paulicians as simple, godly folk who had kept an earlier (sc. Adoptionistic) form of Christianity (ibid., introduction).[8]

Doctrines

Little is known of the tenets of the Paulicians, as we are confined to the reports of opponents and a few fragments of Sergius' letters which they have preserved. Their system was dualistic,[12] although some have argued that it was actually adoptionist in nature.[13][14]

In it there are two principles, two kingdoms. The Evil Spirit is the author of, and lord of, the present visible world; the Good Spirit, of the future world.[2] Of their views about the creation of man, little is known but what is contained in the ambiguous words of Sergius. This passage seems to teach that Adam's sin of disobedience was a blessing in disguise, and that a greater sin than his is the sin against the Church.

The Paulicians accepted the four Gospels; fourteen Epistles of Paul; the three Epistles of John; the epistles of James and Jude; and an Epistle to the Laodiceans, which they professed to have. They rejected the Tanakh, also known as the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament, as well as the Orthodox-Catholic title Theotokos ("Mother of God"), and refused all veneration of Mary.[2] Christ came down from heaven to emancipate humans from the body and from the world, which are evil. The reverence for the Cross they looked upon as heathenish. The outward administration of the sacraments of the Lord's Supper and baptism they rejected. Their places of worship they called "places of prayer." Although they were ascetics, they made no distinction in foods, and practiced marriage.

Certain scholars argue the Paulicians were not a branch of the Manichæans,[citation needed] as Photius, Petrus Siculus, and many modern authors have held. Both sects were dualistic, but the Paulicians ascribed the creation of the world to the evil God (demiurge) and, unlike the Manichæans, held the New Testament Scriptures in higher honor. According to some, Manes himself, the creator of the system of thought of Manichaeanism, was given little reverence or regard, in some accounts the Paulicians merely comparing him with the Buddha.[citation needed] Gieseler and Neander, with more probability, derive the sect from the Marcionites. Muratori, Mosheim, Gibbon, Gilles Quispel and others regard the Paulicians as the forerunners of the Cathars, but the differences between them in organization, ascetic practices, etc., undermine this opinion. Academic consensus, in fact, is not uniform as to these subjects.[citation needed]

Frederick Conybeare in his edition of The Key of Truth concluded that "The word Trinity is nowhere used, and was almost certainly rejected as being unscriptural."[15]

In all probability, the Paulician movement and its metaphysical philosophy or ideology was brought about by a distinctive synthesis of several similar and variable strains: the popularized ideas of both Manes and Marcion; Euchite or "Messalian", semi-Nestorian and Iranian religious concepts; preexisting "heathen" undercurrents; and some find traces of even distant Eurasian shamanistic elements. The sparseness of empirical, academically verifiable data subject to confirmation make the matter relatively nebulous. Yet, it can be very broadly stated, overall, populist, late-Marcionism fused to a type of idiosyncratic Manichæism of similarly popularized form, appear to be the two main constituents of Paulician spiritual doctrine.

See also

- Paulician dialect

- Banat Bulgarian dialect

- Albigensians

- Bogomilism

- Tondrakians

- Pomaks

- Novgorod Codex

- Nane (goddess)

Additional reading

- Herzog, "Paulicians," Philip Schaff, ed., A Religious Encyclopaedia or Dictionary of Biblical, Historical, Doctrinal, and Practical Theology, 3rd edn, Vol. 2. Toronto, New York & London: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1894. pp. 1776–1777

- Nikoghayos Adontz: Samuel l'Armenien, Roi des Bulgares. Bruxelles, Palais des academies, 1938.

- (Armenian) Hrach Bartikyan, Quellen zum Studium der Geschichte der paulikianischen Bewegung, Eriwan 1961.

- The Key of Truth, A Manual of the Paulician Church of Armenia, edited and translated by F. C. Conybeare, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1898.

- S. B. Dadoyan: The Fatimid Armenians: Cultural and Political Interaction in the Near East, Islamic History and Civilization, Studies and Texts 18. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1997, Pp. 214.

- Nina G. Garsoian: The Paulician Heresy. A Study in the Origin and Development of Paulicianism in Armenia and the Eastern Provinces of the Byzantine Empire. Publications in Near and Middle East Studies. Columbia University, Series A 6. The Hague: Mouton, 1967, 296 pp.

- Nina G. Garsoian: Armenia between Byzantium and the Sasanians, London: Variorum Reprints, 1985, Pp. 340.

- Newman, A.H. (1951). "Paulicians". In Samuel Macaulay Jackson. New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge VIII. Baker Book House, Michigan. pp. 417–418.

- Vahan M. Kurkjian: A History of Armenia (Chapter 37, The Paulikians and the Tondrakians), New York, 1959, 526 pp.

- A. Lombard: Pauliciens, Bulgares et Bons-hommes, Geneva 1879

- Vrej Nersessian: The Tondrakian Movement, Princeton Theological Monograph Series, Pickwick Publications, Allison Park, Pennsylvania, 1948, Pp. 145.

References

- ↑ New Advent Catholic Encyclopaedia

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 (Armenian) Melik-Bakhshyan, Stepan. «Պավլիկյան շարժում» (The Paulician movement). Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. vol. ix. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1983, pp. 140-141.

- ↑ Nersessian, Vrej (1998). The Tondrakian Movement: Religious Movements in the Armenian Church from the 4th to the 10th Centuries. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-900707-92-5.

- ↑ Constantine-Silvanus." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Accessed 2 September 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Petrus Siculus, "Historia Manichaeorum", op. cit., 45

- ↑ Norwich, John Julius: A Short History of Byzantium Knopf, New York, 1997, page 140

- ↑ Digenis Akritas: The Two-Blooded Border Lord. Trans. Denison B. Hull. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1972

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 New Advent article on the Paulicians

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N6eslcDWaks

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=isp7nXsrCJY

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&v=41ZlckR_sHQ&feature=endscreen

- ↑ Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford: University of Stanford Press. p. 448. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- ↑ Garsoian, Nina (1967). The Paulician Heresy: A Study of the Origin and Development of Paulicianism in Armenia and the Eastern Provinces of the Byzantine Empire. The Hague: Mouton.

- ↑ Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- ↑ The Key of Truth. A Manual of the Paulician Church of Armenia. Page xxxv Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare "The context implies that the Paulicians of Khnus had objected as against those who deified Jesus that a circumcised man could not be God. ... The word Trinity is nowhere used, and was almost certainly rejected as being unscriptural."

External links

- Paulicianism article at Medieval Church.org.uk

- Paulicianism article at The Catholic Encyclopedia, Newadvent.org

- Paulicianism article at 1911encyclopedia.org

- http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Paulicians

- Leon Arpee. Armenian Paulicianism and the Key of Truth. The American Journal of Theology, Chicago, 1906, vol. £, p. 267-285

- L. P. Brockett, The Bogomils of Bulgaria and Bosnia - The Early Protestants of the East