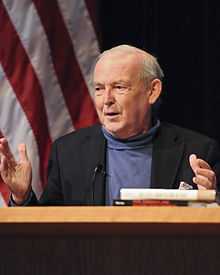

Paul Kennedy

| Paul M. Kennedy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1945 Wallsend, Northumberland |

| Residence | United States |

| Institutions |

University of East Anglia Yale University |

| Alma mater |

Newcastle University St Antony's College, Oxford |

| Doctoral advisor | A. J. P. Taylor, John Andrew Gallagher |

| Doctoral students | Richard Drayton, Mary E. Sarotte |

Paul Michael Kennedy CBE FBA (born 1945) is a British historian at Yale University specialising in the history of international relations, economic power and grand strategy. He has published prominent books on the history of British foreign policy and Great Power struggles. He emphasizes the changing economic power base that undergirds military and naval strength, noting how declining economic power leads to reduced military and diplomatic weight.

Life

Kennedy was born in Wallsend, Northumberland, and attended St. Cuthbert's Grammar School in Newcastle upon Tyne. Subsequently, he graduated with first-class honours in history from Newcastle University and obtained his doctorate from St. Antony's College, Oxford, under the supervision of A. J. P. Taylor and John Andrew Gallagher. He was a member of the History Department at the University of East Anglia between 1970 and 1983. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, a former Visiting Fellow of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, United States, and of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in Germany. In 2007-8, Kennedy was the Phillipe Roman Professor of History and International Affairs at the London School of Economics.

In 1983 he was named the J. Richardson Dilworth professor of British history at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. He is now also the Director of International Security Studies and along with John Lewis Gaddis and Charles Hill, teaches the Studies in Grand Strategy course there. In 2012, Professor Kennedy began teaching a new Yale course, "Military History of the West Since 1500", elaborating on his presentation of military history as inextricably intertwined with economic power and technological progress.

His most famous book, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, has been translated into 23 languages and assesses the interaction between economics and strategy over the past five centuries. The book was incredibly well received by fellow historians, with A. J. P. Taylor labelling it "an encyclopaedia in itself" and Sir Michael Howard crediting it as "a deeply humane book in the very best sense of the word".[1][2]

His most recent book is The Parliament of Man, in which he contemplates the past and future of the United Nations.

He is on the editorial board of numerous scholarly journals and writes for The New York Times, The Atlantic, and many foreign-language newspapers and magazines. His monthly column on current global issues is distributed worldwide by the Los Angeles Times Syndicate/Tribune Media Services.[3]

In 2010 he delivered the first Lucy Houston Lecture in Cambridge on the subject "Innovation and Industrial Regeneration".[4][5]

Honours

He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 2001 and elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 2003. The National Maritime Museum awarded him its Caird Medal in 2005 for his contributions to naval history.

Interpretations

Rise and Fall

In The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1987), Kennedy argues that economic strength and military power have been highly correlated in the rise and fall of major nations since 1500. He shows that expanding strategic commitments lead to increases in military expenditures that eventually overburden a country's economic base, and cause its long-term decline. His book reached a wide audience of policy makers when it suggested that the United States and the Soviet Union were presently experiencing the same historical dynamics that previously affected Spain, the Netherlands, France, Great Britain, and Germany, and that the United States must come to grips with its own "imperial overstretch".[6]

However, the Cold War ended two years after Kennedy's book appeared, validating his thesis regarding the Soviet Union, but leaving the United States as the sole superpower and, apparently, at the peak of its economy. Nau (2001) contends that Kennedy's "realist" model of international politics underestimates the power of national, domestic identities or the possibility of the ending of the Cold War and the growing convergence of democracy and markets resulting from the democratic peace that followed.

World War I

In explaining why neutral Britain went to war with Germany, Kennedy (1980) recognized it was critical for war that Germany become economically more powerful than Britain, but he downplays the disputes over economic trade imperialism, the Baghdad Railway, confrontations in Eastern Europe, high-charged political rhetoric and domestic pressure-groups. Germany's reliance time and again on sheer power, while Britain increasingly appealed to moral sensibilities, played a role, especially in seeing the invasion of Belgium as a necessary military tactic or a profound moral crime. The German invasion of neutral Belgium was not important because the British decision had already been made and the British were more concerned with the fate of France (pp. 457–62). Kennedy argues that by far the main reason was London's fear that a repeat of 1870, when Prussia and the German states smashed France, would mean that Germany, with a powerful army and navy, would control the English Channel and northwest France. British policy-makers insisted that that would be a catastrophe for British security.[7]

Notable students

- Geoffrey Wawro (1992)

- Richard Drayton (1999)

Bibliography

- Engineers of Victory: The Problem Solvers Who Turned the Tide in the Second World War (2013) ISBN 978-1-4000-6761-9

- The Parliament of Man: The Past, Present, and Future of the United Nations (2006) ISBN 0-375-50165-7

- From War to Peace: Altered Strategic Landscapes in the Twentieth Century (2000) ISBN 0-300-08010-7

- Preparing for the Twenty-first Century (1993) ISBN 0-394-58443-0

- Grand Strategies in War and Peace (editor) (1991) ISBN 0-300-04944-7

- The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914 (2nd edn. 1988) ISBN 1-57392-301-X

- The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (1987) ISBN 0-394-54674-1

- The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (1986) ISBN 1-57392-278-1 (2nd edn. 2006) ISBN 1-59102-374-2

- Strategy and Diplomacy 1870-1945 (1983) ISBN 0-00-686165-2

- The Realities Behind Diplomacy: Background Influences on British External Policy 1865-1980 (1981)

- The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860-1914 (1980)

- The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (1976, paperback reissue 2001, 2004)

- The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878-1900 (1974)

- Conquest: The Pacific War 1943-45 (1973)

- Pacific Onslaught 1941-43 (1972)

Further reading

- Nau, Henry R. "Why 'The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers' was wrong", Review of International Studies, October 2001, Vol. 27, Issue 4, pp. 579–592.

- Eugene L. Rasor, British Naval History since 1815: A Guide to the Literature. New York: Garland, 1990, pp. 41–54.

- Patrick D. Reagan, "Strategy and History: Paul Kennedy's The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers," Journal of Military History, July 89, Vol. 53#3, pp. 291–306 in JSTOR.

References

- ↑ The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (1987) ISBN 0-394-54674-1 - Synopsis.

- ↑ "Threats to the West," an interview with Paul Kennedy.

- ↑ http://www.yale.edu/history/faculty/kennedy.html

- ↑ The Lucy Houston Lecture 2010 The Lucy Houston Lecture 2010

- ↑ The Guardian, 16 November 2011 Why doesn't Britain make things anymore?

- ↑ Patrick D. Reagan, "Strategy and History: Paul Kennedy's The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers", Journal of Military History, July 1989, Vol. 53#3, pp. 291-306 in JSTOR.

- ↑ Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914 (1980), pp. 464-70.

External links

|