Paul Kammerer

| Paul Kammerer | |

|---|---|

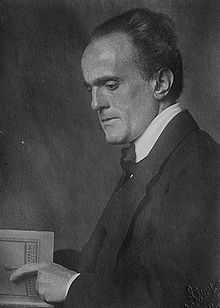

Paul Kammerer, 1924 | |

| Born |

17 August 1880 Vienna |

| Died |

23 September 1926 Puchberg am Schneeberg Suicide |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Known for | Lamarckian theory of inheritance, herpetological research |

Paul Kammerer (17 August 1880, in Vienna – 23 September 1926, in Puchberg am Schneeberg) was an Austrian biologist who studied and advocated the now largely abandoned Lamarckian theory of inheritance – the notion that organisms may pass to their offspring characteristics they have acquired in their lifetime. He began his academic career at the Vienna Academy studying music but graduated with a degree in biology.

Work

Kammerer undertook numerous biology experiments, largely involving interfering with the breeding and development of amphibians. He coerced ovoviviparous fire salamanders to become viviparous, and viviparous alpine salamanders to become ovoviviparous. In lesser-known experiments, he manipulated and bred olms. He made olms produce live young, and he bred dark-colored olms with full vision. He supported the Lamarckian theory of the heritability of acquired characteristics, and experimented extensively in an effort to prove this theory.[1]

Kammerer succeeded in making midwife toads breed in the water by increasing the temperature of their tanks, forcing them to retreat to the water to cool off. The male midwife toads were not genetically programmed for the underwater mating that necessarily followed and thus, over the span of two generations, Kammerer reported that his midwife toads were exhibiting black nuptial pads on their feet to give them more traction in this underwater mating process. While the prehistoric ancestors of midwife toads had these pads, Kammerer considered this an acquired characteristic brought about by adaptation to environment.[1] Claims arose that the result of the experiment had been falsified. The most notable of these claims was made by Dr. G. K. Noble, Curator of Reptiles at the American Museum of Natural History, in the scientific journal Nature. Noble claimed that the black pads actually had a far more mundane explanation: it had simply been injected there with Indian ink.[2]

However, it has been reported that Kammerer previously exhibited toad specimens in England with inspection by eminent zoologists, all of whom doubted the validity of Lamarckism (a non-Darwinian theory of evolution inconsistent with modern genetics and biology) but none suggesting the accusation of irregularity later levied by Noble. Hence, the possibility of sabotage committed shortly before Noble's visit to Vienna (after Kammerer's departure from the Institute) has been raised,[citation needed] with further reference being made to the many European biologists that had visited Kammerer in Vienna and to the widely availability of photographs and reports of his work. This report notes that Kammerer approved Noble's inspection of the specimen found to have been tampered with, and that Kammerer expressed great astonishment at Noble's observation.[citation needed] Moreover, it has been noted that Kammerer had also experimented with sea squirts, salamanders, and other animals and argued that these prior experiments also provided substantial evidence of Lamarckian inheritance; as such he regarded midwife toad foot pad inheritance to be of relatively minor significance in the overall argument.[citation needed]

Six weeks after the accusation by Noble, Kammerer committed suicide in the forest of Schneeberg,[1] an event whose complex meaning is discussed by journalist Arthur Koestler.[3]

Aftermath

The biologist Ernest MacBride supported the experiments of Kammerer and claimed they were "perfectly sound" but would have to be repeated if they were to be accepted by other scientists.[4] Interest in Kammerer revived in 1971 with the publication of Arthur Koestler's book, The Case of the Midwife Toad. Koestler surmised that Kammerer's experiments on the midwife toad may have been tampered with by a Nazi sympathizer at the University of Vienna. Certainly, as Koestler writes, "the Hakenkreuzler, the swastika-wearers, as the Austrian Nazis of the early days were called, were growing in power. One center of ferment was the University of Vienna[5] where, on the traditional Saturday morning student parades, bloody battles were fought. Kammerer was known by his public lectures and newspaper articles as an ardent pacifist and Socialist; it was also known that he was going to build an institute in Soviet Russia. "An act of sabotage in the laboratory would have been…in keeping with the climate of those days."

As a consequence of Noble's refutation (see above), interest in Lamarckian inheritance diminished except in the Soviet Union where it was championed by Lysenko. Biology professor Harry Gershenowitz attempted to duplicate Kammerer's experiment with a related species Bombina orientalis but due to lack of funds had to terminate the experiment.[6]

Historian of biology Sander Gliboff, Ivan Slade Prize winner (British Society for the History of Science) and Professor in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University, has commented that, though Kammerer's conclusions proved false, his evidence was probably genuine and that he did not simply argue for Lamarckism and against Darwinism as those theories are now understood. Rather, if we look beyond the scandal, the story shows us much about the competing theories of biological and cultural evolution and the range of new ideas about heredity and variation in early 20th-century biology and the changes in experimental approach that have occurred since that time.[7]

In 2009, developmental biologist Alexander Vargas, Professor in the Department of Biology, University of Chile, suggested that the inheritance of acquired traits (Lamarckian inheritance) that Kammerer reported to observe in his toad experiments could be authentic, and explainable by results from the emerging field of epigenetics.[8][9] In Vargas' view, Kammerer could actually be considered the discoverer of non-Mendelian, epigenetic inheritance, wherein chemical modifications to parental DNA (e.g., through DNA methylation) are passed on to subsequent generations. Furthermore, In Vargas' view, the parent-of-origin effect poorly understood at the time of Kammerer's work might be explained retrospectively, in relation to similar effects seen in other organisms. Professor Gliboff of Indiana University (see above) has subsequently argued that Vargas "constructed his model without first reading Kammerer's original articles", and that Vargas is "seriously misinformed about what Kammerer did and what the results even were", such that Vargas' "model... cannot explain the results... originally reported...". Gliboff goes on to strongly challenge Kammerer's being given credit for discovery of parent-of-origin effects, and to state that "Vargas' historical inferences about the Kammerer affair... [and] negative reactions of geneticists... are unsupported and do not stand up to scrutiny." [10] Hence, the reinterpretation of Kammerer's work in light of epigenetic discoveries remains controversial.

Seriality theory

Kammerer's other passion was collecting coincidences. He published a book with the title Das Gesetz der Serie (The Law of the Series; never translated into English) in which he recounted some 100 anecdotes of coincidences that had led him to formulate his theory of Seriality.

He postulated that all events are connected by waves of seriality. These unknown forces would cause what we would perceive as just the peaks, or groupings and coincidences. Kammerer was known to, for example, make notes in public parks of what numbers of people were passing by, how many carried umbrellas etc. Albert Einstein called the idea of Seriality "interesting, and by no means absurd",[11] while Carl Jung drew upon Kammerer's work in his essay Synchronicity. Koestler reported that, when researching for his biography about Kammerer, he himself was subjected to "a meteor shower" of coincidences - as if Kammerer's ghost were grinning down at him saying, "I told you so!".[12]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Schmuck, Thomas (2000). "The Midwife Toad and Human Progress". In Hofrichter, Robert. Amphibians: The World of Frogs, Toads, Salamanders and Newts (New York: Firefly). pp. 212–213. ISBN 1-55209-541-X.

- ↑ Nature, 7 August 1926

- ↑ Arthur Koestler. (1973). The Case of the Midwife Toad. Vintage (first published 1971). ISBN 978-0394718231

- ↑ Ernest MacBride. (1929). Evolution. J. Cape & H. Smith. p. 38

- ↑ University 1938-1945

- ↑ Harry Gerschenowitz. (1983). Arthur Koestler’s Osculation with Lamarckism and Neo-Lamarckism. IJHS 18, 1-8.

- ↑ Gliboff, Sander (2005). ""Protoplasm…is soft wax in our hands": Paul Kammerer and the art of biological transformation". Endeavour 29 (4): 162–167. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2005.10.001. PMID 16271762.

- ↑ Pennisi, Elizabeth (4 September 2009). "The Case of the Midwife Toad: Fraud or Epigenetics?". Science 325 (5945): 1194–1195. doi:10.1126/science.325_1194. PMID 19729631.

- ↑ Alexander O. Vargas. (2009). Did Paul Kammerer discover epigenetic inheritance? A modern look at the controversial midwife toad experiments. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol, 312(7):667-78. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21319

- ↑ Gliboff, Sander AO (2009) "Did Paul Kammerer discover epigenetic inheritance? No and why not", J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol, 314(8):616-24. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21374

- ↑ Arthur Koestler. (1972). The Roots of Coincidence. Vintage. p. 87. ISBN 978-0394719344

- ↑ Alister Hardy, Robert Harvie, Arthur Koestler. (1973). The Challenge of Chance: Experiments and Speculations. Hutchinson. p. 198

Further reading

- Arthur Koestler. (1971). The Case of the Midwife Toad. London: Hutchinson.

- Sermonti, G (2000). "Epigenetic heredity. In praise of Paul Kammerer". Riv. Biol. 93 (1): 5–12. PMID 10901054.

- Lachman, E (March 1976). "Famous scientific hoaxes". The Journal of the Oklahoma State Medical Association 69 (3): 87–90. PMID 775032.

- Meinecke, G (September 1973). "[The tragedy about Paul Kammerer. A scientific psychological example]". Die Medizinische Welt 24 (38): 1462–6. PMID 4587964.

External links

|