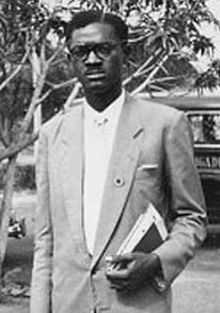

Patrice Lumumba

| Patrice Lumumba | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Prime Minister of the Republic of Congo-Léopoldville | |

| In office 24 June 1960 – 14 September 1960 | |

| Deputy | Antoine Gizenga |

| Preceded by | Colonial government |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Ileo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Patrice Émery Lumumba 2 July 1925 Onalua, Katakokombe, Belgian Congo |

| Died | 17 January 1961 (aged 35) Elisabethville, State of Katanga |

| Political party | MNC |

| Spouse(s) | Pauline Lumumba |

| Children | François Lumumba Patrice Lumumba, Jr. Julienne Lumumba Roland Lumumba Guy-Patrice Lumumba |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Patrice Émery Lumumba (born Élias Okit'Asombo;[1][2][3] 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese independence leader and the first democratically elected Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo) after he helped win its independence from Belgium in June 1960.

Within twelve weeks, Lumumba's government was deposed in a coup during the Congo Crisis. The main reason why he was ousted from power was his opposition to Belgian-backed secession of the mineral-rich Katanga province.[4]

He was subsequently imprisoned by state authorities under Joseph-Desiré Mobutu and executed by firing squad under the command of the secessionist Katangan authorities. The United Nations, which he had asked to come to the Congo, did not intervene to save him. Belgium, the United States (via the CIA), and the United Kingdom (via MI6) have all been implicated in Lumumba's death.[5][6][7]

Early life and career

Lumumba was born to a farmer, François Tolenga Otetshima, and his wife, Julienne Wamato Lomendja, in Onalua in the Katakokombe region of the Kasai province of the Belgian Congo.[8] He was a member of the Tetela ethnic group and was born with the name Élias Okit'Asombo. His original surname means "heir of the cursed" and is derived from the Tetela words okitá/okitɔ́ ('heir, successor')[9] and asombó ('cursed or bewitched people who will die quickly').[10] He had three brothers (Charles Lokolonga, Émile Kalema, and Louis Onema Pene Lumumba) and one half-brother (Tolenga Jean).[8] Raised in a Catholic family, he was educated at a Protestant primary school, a Catholic missionary school, and finally the government post office training school, passing the one-year course with distinction. He subsequently worked in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) and Stanleyville (now Kisangani) as a postal clerk and as a travelling beer salesman. In 1951, he married Pauline Opangu. In 1955, Lumumba became regional head of the Cercles of Stanleyville and joined the Liberal Party of Belgium, where he worked on editing and distributing party literature. After traveling on a three-week study tour in Belgium, he was arrested in 1955 on charges of embezzlement. His two-year sentence was commuted to twelve months after it was confirmed by Belgian lawyer Jules Chrome that Lumumba had returned the funds, and he was released in July 1956. After his release, he helped found the broad-based Mouvement national congolais (MNC) in 1958, later becoming the organization's president. Lumumba and his team represented the MNC at the All-African Peoples' Conference in Accra, Ghana, in December 1958. At this international conference, hosted by Pan-African President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Lumumba further solidified his Pan-Africanist beliefs. Lumumba spoke Tetela, French, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba.[8]

Leader of MNC

In late October 1959, Lumumba, as leader of the organization, was arrested for inciting an anti-colonial riot in Stanleyville where thirty people were killed; he was sentenced to 69 months in prison. The trial's start date of 18 January 1960, was also the first day of a round-table conference in Brussels to finalize the future of the Congo. Despite Lumumba's imprisonment at the time, the MNC won a convincing majority in the December local elections in the Congo.

Independence Day was celebrated on 30 June in a ceremony attended by many dignitaries including Belgian King Baudouin and the foreign press.[11] Baudouin's speech praised developments under colonialism, his reference to the "genius" of his great-granduncle Léopold II of Belgium glossing over atrocities committed during the Congo Free State.[5] The King continued, "Don't compromise the future with hasty reforms, and don't replace the structures that Belgium hands over to you until you are sure you can do better... Don't be afraid to come to us. We will remain by your side, give you advice."[12] While President Kasa-Vubu thanked the King, Lumumba, who was not scheduled to speak, delivered an impromptu speech which reminded the audience that the independence of the Congo was not granted magnanimously by Belgium:[11][12]

For this independence of the Congo, even as it is celebrated today with Belgium, a friendly country with whom we deal as equal to equal, no Congolese worthy of the name will ever be able to forget that it was by fighting that it has been won, a day-to-day fight, an ardent and idealistic fight, a fight in which we were spared neither privation nor suffering, and for which we gave our strength and our blood. We are proud of this struggle, of tears, of fire, and of blood, to the depths of our being, for it was a noble and just struggle, and indispensable to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed upon us by force.[12]

In contrast to the relatively harmless speech of President Kasa-Vubu, Lumumba's reference to the suffering of the Congolese under Belgian colonialism stirred the crowd while simultaneously humiliating and alienating the King and his entourage. Some media claimed at the time that he ended his speech by ad-libbing, Nous ne sommes plus vos macaques! (We are no longer your monkeys!)—referring to a common slur used against Africans by Belgians, however, these words are neither in his written text nor in radio tapes of his speech.[6][13] Lumumba was later harshly criticised for what many in the Western world—but virtually none in Africa—described as the inappropriate nature of his speech.[14]

Actions as Prime Minister

A few days after Congo gained its independence, Lumumba made the fateful decision to raise the pay of all government employees except for the army. Many units of the army also had strong objections toward the uniformly Belgian officers; General Janssens, the army head, told them their lot would not change after independence, and they rebelled in protest. The rebellions quickly spread throughout the country, leading to a general breakdown in law and order. Although the trouble was highly localized, the country seemed to be overrun by gangs of soldiers and looters, causing a media sensation, particularly over Europeans fleeing the country.[15]

The province of Katanga declared independence under regional premier Moïse Tshombe on 11 July 1960 with support from the Belgian government and mining companies such as Union Minière.[16] Despite the arrival of UN troops, unrest continued. Since the United Nations refused to help suppress the rebellion in Katanga, Lumumba sought Soviet aid in the form of arms, food, medical supplies, trucks, and planes to help move troops to Katanga. Lumumba's decisive actions alarmed his colleagues and President Joseph Kasa-Vubu, who preferred a more moderate political approach.[17]

Deposition and death

In September, the President dismissed Lumumba from government. Lumumba immediately protested the legality of the President's actions. In retaliation, Lumumba declared Kasa-Vubu deposed and won a vote of confidence in the Senate, while the newly appointed prime minister failed to gain parliament's confidence. The country was torn by two political groups claiming legal power over the country.

On 14 September, a coup d’état organised by Colonel Joseph Mobutu incapacitated both Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu.[15] Lumumba was placed under house arrest at the Prime Minister's residence, although UN troops were positioned around the house to protect him. Nevertheless, Lumumba decided to rouse his supporters in Haut-Congo. Smuggled out of his residence at night, he escaped to Stanleyville, where his intention apparently was to set up his own government and army.[18]

Pursued by troops loyal to Mobutu he was finally captured in Port Francqui on 1 December 1960 and flown to Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) in ropes, not handcuffs. Mobutu claimed Lumumba would be tried for inciting the army to rebellion and other crimes.

UN response

United Nations Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld made an appeal to Kasa-Vubu asking that Lumumba be treated according to due process of law. The USSR denounced Hammarskjöld and the Western powers as responsible for Lumumba's arrest and demanded his release.

The UN Security Council was called into session on 7 December 1960 to consider Soviet demands that the UN seek Lumumba's immediate release, the immediate restoration of Lumumba as head of the Congo government, the disarming of the forces of Mobutu, and the immediate evacuation of Belgians from the Congo. Hammarskjöld, answering Soviet attacks against his Congo operations, said that if the UN forces were withdrawn from the Congo "I fear everything will crumble."

The threat to the UN cause was intensified by the announcement of the withdrawal of their contingents by Yugoslavia, the United Arab Republic, Ceylon, Indonesia, Morocco, and Guinea. The pro-Lumumba resolution was defeated on 14 December 1960 by a vote of 8–2. On the same day, a Western resolution that would have given Hammarskjöld increased powers to deal with the Congo situation was vetoed by the Soviet Union.

Final days

Lumumba was sent first on 3 December, to Thysville military barracks Camp Hardy, 150 km (about 100 miles) from Léopoldville. However, when security and disciplinary breaches threatened his safety, it was decided that he should be transferred to the State of Katanga, which had recently declared independence from Congo.

Lumumba was forcibly restrained on the flight to Elizabethville (now Lubumbashi) on 17 January 1961.[19] On arrival, he was conducted under arrest to Brouwez House where he was brutally beaten and tortured by Katangan and Belgian officers,[20] while President Tshombe and his cabinet decided what to do with him.[21][22][23]

Death by firing squad

Later that night, Lumumba was driven to an isolated spot where three firing squads had been assembled. The Belgian Commission (see below) has found that the execution was carried out by Katanga's authorities.

It reported that President Tshombe and two other ministers were present with four Belgian officers under the command of Katangan authorities. Lumumba and two ministers from his newly formed independent government (and who had also been tortured), Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, were lined up against a tree and shot one at a time. The execution probably took place on 17 January 1961 between 21:40 and 21:43 according to the Belgian report.

Announcement of death

No statement was released until three weeks later despite rumours that Lumumba was dead. His death was formally announced on Katangan radio, when it was alleged that he escaped and was killed by enraged villagers.

After the announcement of Lumumba's death, street protests were organized in several European countries; in Belgrade, capital of Yugoslavia, protesters sacked the Belgian embassy and confronted the police, and in London a crowd marched from Trafalgar Square to the Belgian embassy, where a letter of protest was delivered and where protesters clashed with police.[24] A demonstration at the United Nations Security Council turned violent and spilled over into the streets of New York City.[25][26]

Foreign involvement in his death

According to Democracy Now!, "Lumumba's pan-Africanism and his vision of a united Congo gained him many enemies. Both Belgium and the United States actively sought to have him killed. The CIA ordered his assassination but could not complete the job. Instead, the United States and Belgium covertly funneled cash and aid to rival politicians who seized power and arrested Lumumba."[27]

Both Belgium and the US were clearly influenced in their unfavourable stance towards Lumumba by the Cold War. He seemed to gravitate around the Soviet Union, although this was not because he was a communist but the only place he could find support in his country's effort to rid itself of colonial rule.[28] The US was the first country from which Lumumba requested help.[29] Lumumba, for his part, not only denied being a Communist, but said he found colonialism and Communism to be equally deplorable, and professed his personal preference for neutrality between the East and West.[30]

Belgian Involvement

According to David Akerman, Ludo de Witte and Kris Hollington,[31] the firing squads were commanded by a Belgian, Captain Julien Gat; another Belgian, Police Commissioner Verscheure, had overall command of the execution site.[32] de Witte found written orders from the Belgian government requesting Lumumba's execution and documents on various arrangements, such as death squads.

On 18 January, panicked by reports that the burial of the three bodies had been observed, members of the execution team went to dig up the bodies and move them to a place near the border with Northern Rhodesia for reburial. Belgian Police Commissioner Gerard Soete later admitted in several accounts that he and his brother led the exhumation (and also a second exhumation, below). Police Commissioner Frans Verscheure also took part.

According to Adam Hochschild, author of a book on the Congo rubber terror, Lumumba's body was later cut up and dissolved in acid by two Belgian agents.[33] On the afternoon and evening of 21 January, Commissioner Soete and his brother dug up Lumumba's corpse for the second time, cut it up with a hacksaw, and dissolved it in concentrated sulfuric acid.[34][35] Only some teeth and a fragment of skull and bullets survived the process, kept as souvenirs.

In an interview on Belgian television in a program on the assassination of Lumumba in 1999, Soete displayed a bullet and two teeth that he boasted he had saved from Lumumba's body.[35] De Witte also mentions that Verscheure kept souvenirs from the exhumation: bullets from the skull of Lumumba.[36]

The Belgian Commission investigating Lumumba's assassination concluded that (1) Belgium wanted Lumumba arrested, (2) Belgium was not particularly concerned with Lumumba's physical well being, and (3) although informed of the danger to Lumumba's life, Belgium did not take any action to avert his death, but the report also specifically denied that Belgium ordered Lumumba's assassination.[37]

Under its own 'Good Samaritan' laws, Belgium was legally culpable for failing to prevent the assassination from taking place and was also in breach of its obligation (under U.N. Resolution 290 of 1949) to refrain from acts or threats "aimed at impairing the freedom, independence or integrity of another state."[38]

Belgian apology

In February 2002, the Belgian government apologized to the Congolese people, and admitted to a "moral responsibility" and "an irrefutable portion of responsibility in the events that led to the death of Lumumba".[39]

United States involvement

The report of 2001 by the Belgian Commission mentions that there had been previous U.S. and Belgian plots to kill Lumumba. Among them was a Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored attempt to poison him, which may have come on orders from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower.[40] CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb was a key person in this by devising a poison resembling toothpaste. In September 1960, Gottlieb brought a vial of the poison to the Congo with plans to place it on Lumumba's toothbrush. [41][42][43][44] However, the plot was later abandoned; the plan is said to have been scrapped because the local CIA Station Chief, Larry Devlin, refused permission.[42][43][45]

However, as Kalb points out in her book, Congo Cables, the record shows that many communications by Devlin at the time urged elimination of Lumumba. [46] Also, the CIA station chief helped to direct the search to capture Lumumba for his transfer to his enemies in Katanga; was involved in arranging his transfer to Katanga; [47] and the CIA base chief in Elizabethville was in direct touch with the killers the night Lumumba was killed. Furthermore, John Stockwell indicates that a CIA agent had the body in the trunk of his car in order to try to get rid of it.[48] Stockwell, who knew Devlin well, felt Devlin knew more than anyone else about the murder.[49]

The inauguration of U.S. President John F. Kennedy in January 1961 caused fear among Mobutu's faction and within the CIA that the incoming administration would shift its favor to the imprisoned Lumumba.[50] Lumumba was killed three days before Kennedy's inauguration on 20 January, though Kennedy would not learn of the killing until 13 February.[51]

Church Committee

In 1975, the Church Committee went on record with the finding that Allen Dulles had ordered Lumumba's assassination as "an urgent and prime objective".[52] Furthermore, declassified CIA cables quoted or mentioned in the Church report and in Kalb (1972) mention two specific CIA plots to murder Lumumba: the poison plot and a shooting plot. Although some sources claim that CIA plots ended when Lumumba was captured, that is not stated or shown in the CIA records.

Rather, those records show two still-partly-censored CIA cables from Elizabethville on days significant in the murder: 17 January, the day Lumumba died, and 18 January, the day of the first exhumation. The former, after a long censored section, talks about where they need to go from there. The latter expresses thanks for Lumumba being sent to them and then says that, had Elizabethville base known he was coming, they would have "baked a snake".[53] This cable goes on to state that the writer's sources (not yet declassified) said that after being taken from the airport Lumumba was imprisoned by "all white guards".[54]

The Committee later found that while the CIA had conspired to kill Lumumba, it was not directly involved in the actual murder.[55]

U.S. government documents

Declassified documents revealed that the CIA had plotted to assassinate Lumumba. These documents indicate that the Congolese leaders who killed Lumumba, including Mobutu and Joseph Kasavubu received money and weapons directly from the CIA.[42][56] This same disclosure showed that at that time the U.S. government believed that Lumumba was a communist.[57]

A recently declassified interview with then-US National Security Council minutekeeper Robert Johnson revealed that U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had said "something [to CIA chief Allen Dulles] to the effect that Lumumba should be eliminated".[55] The interview from the Senate Intelligence Committee's inquiry on covert action was released in August 2000.

British involvement

In April 2013, in a letter to the London Review of Books, a British parliamentarian, Lord David Lea reported having discussed Lumumba's death with Baroness Park shortly before she died in March 2010. Park had been an MI6 officer posted to Leopoldville at the time of Lumumba's death, and was later a semi-official spokesperson for MI6 in the House of Lords.[58]

According to Lea, when he mentioned "the uproar" surrounding Lumumba's abduction and murder, and recalled the theory that MI6 might have had "something to do with it", she replied, "We did. I organised it."[59] BBC reported that, subsequently, "Whitehall sources" described the claims of MI6 involvement as "speculative".[60]

Legacy

"Today, it is impossible to touch down at the (far from modernized) airport of Lubumbashi in the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo without a shiver of recollection of the haunting photograph taken of Lumumba there shortly before his assassination, and after beatings, torture and a long, long flight in custody across the vast country which had so loved him."

| “ | We must move forward, striking out tirelessly against imperialism. From all over the world we have to learn lessons which events afford. Lumumba's murder should be a lesson for all of us. | ” |

Political

Patrice Lumumba was Prime Minister of The Congo for 81 days, from June 23 to September 14, 1960. To his supporters, Lumumba was an altruistic man of strong character. He favoured a unitary Congo and opposed division of the country along ethnic or regional lines.[63][64] Like many other African leaders, he supported pan-Africanism and liberation for colonial territories.[65] He proclaimed his regime one of "positive neutralism,"[66] defined as a return to African values and rejection of any imported ideology, including that of the Soviet Union: "We are not Communists or Catholics. We are African nationalists."[67]

2006 Congolese elections

The image of Patrice Lumumba continues to serve as an inspiration in contemporary Congolese politics. In the 2006 elections, several parties claimed to be motivated by his ideas, including the People's Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD), the political party initiated by the incumbent President Joseph Kabila.[68] Antoine Gizenga, who served as Lumumba's Deputy Prime Minister in the post-independence period, was a 2006 Presidential candidate under the Unified Lumumbist Party (Parti Lumumbiste Unifié (PALU))[69] and was named prime minister at the end of the year. Other political parties that directly utilise his name include the Mouvement National Congolais-Lumumba (MNC-L) and the Mouvement Lumumbiste (MLP).

Family and politics

Patrice Lumumba's family is actively involved in contemporary Congolese politics. Patrice Lumumba was married to Pauline Lumumba and had five children; François was the eldest followed by Patrice Junior, Julienne, Roland and Guy-Patrice Lumumba. François was 10 years old when Patrice died. Before his imprisonment, Patrice arranged for his wife and children to move into exile in Egypt, where François spent his childhood, then went to Hungary for education (he holds a doctorate in political economics).

Lumumba's youngest son, Guy-Patrice, born six months after his father's death, was an independent presidential candidate in the 2006 elections,[70] but received less than 10% of the vote.

Tributes

- In 1966 Patrice Lumumba's image was rehabilitated by the Mobutu regime and he was proclaimed a national hero and martyr in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. By a presidential decree, the Brouwez House, site of Lumumba's brutal torture on the night of his murder, became a place of pilgrimage in the Congo.[71]

- A major transportation artery in Kinshasa, the Lumumba Boulevard, is named in his honour. The boulevard goes past an interchange with a giant tower, the Tour de l'Echangeur (the main landmark of Kinshasa) commemorating him. On the tower's plaza, the first Kabila regime erected a tall statue of Lumumba with a raised hand, greeting people coming from N'djili Airport.

- In Bamako, Mali, Lumumba Square is a large central plaza with a life-size statue of Lumumba, a park with fountains, and a flag display. Around Lumumba Square are various businesses, embassies and Bamako's largest bank.

- Streets were also named after him in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia, in Budapest, Hungary (between 1961 and 1990); Jakarta (between 1961 to 1967); Gaborone, Botswana; Belgrade, Serbia; Sofia and Plovdiv, Bulgaria (until 1991-2) Skopje, Republic of Macedonia; Bata and Malabo, Equatorial Guinea; Tehran, Iran; Algiers, Algeria (Rue Patrice Lumumba);[72] Santiago de Cuba, Cuba (since 1960, formerly Avenida de Bélgica); Łódź, Warsaw, Poland; Kiev, Donetsk, Ukraine; Perm, Russia; Rabat, Morocco; Maputo, Mozambique; Enugu, Nigeria; Leipzig, Germany; Lusaka, Zambia ("Lumumba Street"); Kampala, Uganda and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania ("Lumumba Avenue"); Tunis, Tunisia; Fort-de-France, Martinique; Montpellier, France; Accra, Ghana; Antananarivo, Madagascar; Rotterdam, Netherlands;Alexandria, Egypt and Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan; Koper, Nabrežje Patricea Lumumbe now renamed to Belveder, Slovenia

- The Peoples' Friendship University of the USSR was renamed "Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University" in 1961, but it was later renamed "The Peoples' Friendship University of Russia" in the post-Soviet landscape in 1992.[73]

- In Kampala, Uganda, "Lumumba Hall" of Residence at Makerere University continues to carry his name.

- "Lumumba" is a popular choice for children's names throughout Africa.[74]

- In 1964 Malcolm X declared Patrice Lumumba "the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent".[75]

- Comedian Patrice O'Neal was named after Lumumba.

- A Lumumba is a popular name for hot or cold long drink of chocolate with rum

Quotations

| “ | Dead, living, free, or in prison on the orders of the colonialists, it is not I who counts. It is the Congo, it is our people for whom independence has been transformed into a cage where we are regarded from the outside… History will one day have its say, but it will not be the history that Brussels, Paris, Washington, or the United Nations will teach, but that which they will teach in the countries emancipated from colonialism and its puppets... a history of glory and dignity. | ” |

— Patrice Lumumba, October 1960[61] |

Bibliography

Writings by Lumumba

- Congo, My Country (1962) London: Pall Mall Press. ISBN 0-269-16092-2. Foreword and notes by Colin Legum; translated by Graham Heath.

- Lumumba Speaks: The Speeches and Writings of Patrice Lumumba, 1958–1961 (1972) Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-53650-4. Editor, Jean Van Lierde; translated by Helen R. Lane.

Writings about Lumumba

- Aimé Césaire, Une Saison au Congo (1966); Eng. trans. by Ralph Manheim, A Season in the Congo (1969). A poetic drama about the career and death of Lumumba.

- W. A. E. Skurnik, African Political Thought: Lumumba, Nkrumah, Touré (Social Science Foundation and Graduate School of International Studies, University of Denver. Monograph series in world affairs, v. 5, no. 3-4), 1968, Denver: University of Denver, ASIN B0006CNYSW.

- Ludo De Witte, The Assassination of Lumumba, trans. by Ann Wright and Renée Fenby, 2002 (orig. 2001), London; New York: Verso, ISBN 1859844103.

- Thomas R. Kanza, Conflict in the Congo: The Rise and Fall of Lumumba (Penguin African library), 1972, New York: Penguin, ISBN 0140410309.

- Robin McKown, Lumumba: A Biography, 1969, London: Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-07776-9.

- G. Heinz and H. Donnay (pseudonyms for J. Brassine and J. Gerard-Libois), Lumumba: The Last Fifty Days, 1980, New York: Grove Press, ASIN B0006C07TQ.

- Panaf, Patrice Lumumba (Panaf Great Lives), 1973, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-901787-31-0.

- Kwame Nkrumah, Challenge of the Congo, 1967, New York: International Publishers.

- Bogumil Jewsiewicki, ed., A Congo Chronicle: Patrice Lumumba in Urban Art, 1999, New York: Museum for African Art, ISBN 0-945802-25-0. The catalogue of a travelling exhibition of contemporary Congolese artists who were inspired by the legacy of Lumumba.

- Barbara Kingsolver's The Poisonwood Bible is a fictional account of an American missionary family in the Congo during the election and assassination of Lumumba. The book is critical of Western governments and their interference in Africa.

- David W. Doyle, Inside Espionage: A Memoir of True Men and Traitors (2000), tells the story of Lumumba's assassination from the point of view of the United States Central Intelligence Agency.

- Godfrey Mwakikagile, Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era, Third Edition, New Africa Press, 2006, "Chapter Six: Congo in The 1960s: The Bleeding Heart of Africa", pp. 147–205, ISBN 978-0980253412; Godfrey Mwakikagile, Africa and America in The 1960s: A Decade That Changed The Nation and The Destiny of A Continent, First Edition, New Africa Press, 2006, ISBN 9780980253429.

Films

- El Congo 1961 – As himself in a documentary.

- Seduto alla sua destra (1968) – A fictional film by writer-director Valerio Zurlini starring Woody Strode as a thinly disguised Lumumba. It was released in the US as Black Jesus.

- Lumumba (2000). Dramatized biography directed by Raoul Peck with Eriq Ebouaney as Lumumba.

- Lumumba: Death of a Prophet (1992). Documentary distributed by California Newsreel.

- Lumumba: Un crime d'Etat (in English Lumumba: A state crime)

- Independence Cha-Cha – The Story of Patrice Lumumba (2009). Documentary produced by Kadi Kabeya.

Archive video and audio

- BBC On This Day – 14 September 1960: Violence Follows Army Coup in Congo

- BBC On This Day – 13 February 1961: EX-Congo PM Declared Dead

- Anti-Belgium Demonstrations Over Congo Crisis 1961

- BBC On This Day – 19 February 1961: Lumumba Rally Clashes with UK Police

Other

- In 1969 students from the Black Student Council and Mexican-American Youth Association of the University of California, San Diego proposed the name Lumumba-Zapata College, for what is now known as Thurgood Marshall College.

- In Viennese coffee houses, Lumumba is a cocoa with rum, Lumumba Coffee a black coffee with rum and whipped cream. Both beverages originate from northern Germany, where they are called Tote Tante (dead aunt, with cocoa) and Pharisäer (Pharisee, with coffee; see Nordstrand, Germany) respectively.[76]

- The rapper Nas dedicates his song "My Country" to Lumumba at the end of the song.

- American stand-up comedian Patrice O'Neal was named after Lumumba.

- An Argentinian reggae band was named Lumumba.

- Colombian salsa musician Yuri Buenaventura composed a song, "Patrice Lumumba", in his honor.

- American songwriter Neil Diamond lists Patrice Lumumba in his song "Done Too Soon".[77]

- In the 1961 song "Top Forty, News, Weather And Sports" by Mark Dinning, the verse "I had Lumumba doing the rumba..." was removed after his death a few weeks after the release of the record. Records in stores were recalled, and new ones without the verse were distributed. Some of the original records survive. The verse can be heard in versions of the song available today.

References

- ↑ Fabian, Johannes (1996). Remembering the Present: Painting and Popular History in Zaire. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0520203761.

- ↑ Willame, Jean-Claude (1990). Patrice Lumumba: La crise congolaise revisitée. Paris: Karthala. pp. 22, 23, 25. ISBN 978-2-86537-270-6.

- ↑ Kanyarwunga, Jean I N (2006). République démocratique du Congo : Les générations condamnées : Déliquescence d'une société précapitaliste. Paris: Publibook. pp. 76, 502. ISBN 9782748333435.

- ↑ Zeilig, Leo (2008). Lumumba: Africa's Lost Leader (Life&Times). Haus Publishing. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-905791-02-6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Adam Hochschild, King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, 1999, Mariner Books, ISBN 0-618-00190-5, ISBN 978-0-618-00190-3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ludo De Witte, The Assassination of Lumumba, Trans. by Ann Wright and Renée Fenby, 2002 (Orig. 2001), London; New York: Verso, ISBN 1-85984-410-3.

- ↑ "Belgium Confronts Its Heart of Darkness". New York Times. NYT. 21 September 2002. p. 9.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Kanyarwunga, Jean I N (2006). République démocratique du Congo : Les générations condamnées : Déliquescence d'une société précapitaliste. Paris: Publibook. p. 76. ISBN 9782748333435.

- ↑ Hagendorens, MGR J (1975). Dictionnaire ɔtɛtɛla-français. Bandundu: Ceeba Publications. pp. 275–76.

- ↑ Hagendorens, MGR J (1975). Dictionnaire ɔtɛtɛla-français. Bandundu: Ceeba Publications. pp. 309, 371.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Independence Day Speech". Africa Within. Retrieved 15 July 2006.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Kamalu, Chukwunyere. The Little African History Book – Black Africa from the Origins of Humanity. page 115.

- ↑ "Marred: Lumumba's offensive speech in King's presence". London: Guardian Unlimited. 1 July 1960. Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- ↑ A History of the Modern World, Johnson P, Weidenfeld, London, (1991)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Larry Devlin, Chief of Station Congo, 2007, Public Affairs, ISBN 1-58648-405-2

- ↑ Osabu-Kle, Daniel Tetteh (2000). Compatible Cultural Democracy. Broadview Press. p. 254. ISBN 1-55111-289-2.

- ↑ Johnson. P, ibid

- ↑ Longman History of Africa, Snellgrove L. and Greenberg K., Longman, London (1973)

- ↑ "Correspondent:Who Killed Lumumba-Transcript". BBC. Retrieved 21 May 2010. 00.35.38–00.35.49

- ↑ Prados, John (2006). Safe for Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 278. ISBN 9781566638234.

- ↑ De Witte, Ludo (2001). The Assassination of Lumumba. Verso Books. p. 136. ISBN 1859844103.

- ↑ "BBC ON THIS DAY – 13 – 1961: Ex-Congo PM declared dead". BBC Online. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ↑ "Erschlagen im Busch". Spiegel Online (in German). 22 June 1961. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ↑ "BBC: "1961: Lumumba rally clashes with UK police"". BBC News. 19 February 2001. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ↑ Mahoney, JFK (1983), p. 72. "In the United States, the news of Lumumba's murder provoked racial riots. During an address by Ambassador Stevenson before the Security Council, a demonstration led by American blacks began in the visitors gallery. It quickly turned into a riot in which eighteen UN guards, two newsmen, and two protestors were injured. Outside of the UN building, fights between whites and blacks broke out. A large protest march into Times Square was halted by mounted police."

- ↑ "Screaming Demonstrators Riot In United Nations Security Council", Lodi News-Sentinel (UPI), 16 February 1961.

- ↑ Patrice Lumumba: 50 Years Later, Remembering the U.S.-Backed Assassination of Congo's First Democratically Elected Leader, Democracy Now! (21 January 2011)

- ↑ Sean Kelly, America's Tyrant: The CIA and Mobutu of Zaire, p. 29

- ↑ Kelly, p. 28

- ↑ Kelly, p. 49

- ↑ Hollington, Kris (2007). Wolves, Jackals and Foxes: The Assassins Who Changed History. True Crime. pp. 50–65. ISBN 978-0-312-37899-8. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ↑ "Correspondent:Who Killed Lumumba-Transcript". BBC. Retrieved 21 May 2010. 00.36.57

- ↑ Hochschild, p. 302.

- ↑ (de Witte 2002:140–143)

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Patrice Lumumba – Mysteries of History". Usnews.com. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ↑ de Witte 2002: 140

- ↑ "Report Reproves Belgium in Lumumba's Death". Belgium; Congo (Formerly Zaire): New York Times. 17 November 2001. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ↑ Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan; Mango, Anthony (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and international agreements. Taylor&Francis. p. 2571. ISBN 0-415-93924-0.

- ↑ "World Briefing | Europe: Belgium: Apology For Lumumba Killing", New York Times, 6 February 2002.

- ↑ Kettle, Martin (10 August 2000). "President 'ordered murder' of Congo leader". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ↑ 6) Plan to poison Congo leader Patrice Lumumba (p. 464), Family jewels CIA documents, on the National Security Archive's website

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 "A killing in Congo". US News. 24 July 2000. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Who killed Lumumba". "Africa Within".

- ↑ Sidney Gottlieb "obituary" "Sidney Gottlieb". Counterpunch.org.

- ↑ "Interview with Mark Garsin". Counterpunch.org.

- ↑ (p. 53, 101, 129–133, 149–152, 158–159, 184–185, 195)

- ↑ (p. 158, Hoyt, Michael P. 2009, "Captive in the Congo: A Consul's Return to the Heart of Darkness")

- ↑ John Stockwell In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story. W.W. Norton, 1978: 105

- ↑ (71–72, 136–137)

- ↑ Mahoney, JFK (1983), pp. 69–70. "The Kasavubu-Mobutu regime began to consider the Kennedy administration a threat to its very survival. The Kennedy plan was seen as evidence of 'a new and unexpected solidarity with the Casablanca powers . . .' (the radical nonaligned African governments that supported Lumumba). [...] The CIA station in Léopoldville bore much of the responsibility for the rupture. It had opposed any political solution to the power struggle and, worse, had fortified the resolve of Kasavubu and Mobutu, Nendaka, and the rest to use violence against others to save themselves. [...] The effect was tragic: reports that the incoming administration planned to liberate the imprisoned Lumumba on the one hand, and the CIA's deadly urgings on the other, acted like a closing vice on the desperate men in Léopoldville."

- ↑ Mahoney, JFK (1983), p. 70. "White House photographer Jacques Lowe caught Kennedy, horror-struck with head in hand, receiving the first news by telephone a full four weeks later on February 13. All the anguished searching for a way around Lumumba had been for naught. Forty-eight hours before Kennedy had even taken the presidential oath, Lumumba was already dead.

- ↑ In Dulles' own words; William Blum, Killing Hope. MBI Publishing Co., 2007: p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7603-2457-8

- ↑ FOIA declassified documents on Lumumba on the CIA website

- ↑ CIA document #CO 1366116

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Martin Kettle, "President 'ordered murder' of Congo leader", The Guardian, 9 August 2000.

- ↑ Stephen Weissman, "Opening the Secret Files on Lumumba's Murder", Washington Post, 21 July 2002.

- ↑ Blaine Harden, Africa: Dispatches from a Fragile Continent, p. 50

- ↑ Ben Quinn, "MI6 'arranged Cold War killing' of Congo prime minister", The Guardian, 1 April 2013.

- ↑ Letters, London Review of Books, 11 April 2013, p.4

- ↑ "MI6 and the death of Patrice Lumumba", BBC News, 2 April 2013

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Africa: A Continent Drenched in the Blood of Revolutionary Heroes by Victoria Brittain, The Guardian, January 17, 2011

- ↑ Ernesto "Che" Guevara (World Leaders Past & Present), by Douglas Kellner, 1989, Chelsea House Publishers, ISBN 1555468357, pg 86

- ↑ "Lumumba Facing Separatist Bids". New York Times. AP. 9 August 1960. p. 1. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ↑ Tanner, Henry (25 August 1960). "Congo Troops Fly To Kasai To Stop Secession Effort; Lumumba Acts to Crush Bid to Create a New State in Area of Tribal Conflict". New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ↑ Gilroy, Harry (1 July 1960). "Lumumba Assails Colonialism as Congo Is Freed". New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ↑ "Lumumba Stops In Tunisia". New York Times. 3 August 1960. p. 3. Retrieved 8 November 2010. "'We want no part of the cold war,' he [Lumumba] continued.. 'We want Africa to remain African with a policy of positive neutralism.'"

- ↑ "Lumumba Charts A Neutral Congo; Premier Rejects a Choice of East or West". New York Times. Reuters. 6 July 1960. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ↑ "Kabila Party formed in DR Congo". BBC News. 2 April 2002. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ↑ "Profile: Congo opposition candidates". BBC News. 25 July 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ↑ "Key Figures in Congo's Electoral Process". United Nations Integrated Regional Information Networks. Archived from the original on 25 July 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ↑ Ludo De Witte, The Assassination of Lumumba, Trans. Wright A and Fenby R, 2002 (Orig. 2001), London; New York: Verso, ISBN 1-85984-410-3, pp. 165.

- ↑ "AFRICA|More killings in Algeria". BBC News. 6 February 1998. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ↑ "From Marxism 101 to Capitalism 101". CNN. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ↑ "Naming children for a head start in Africa". BBC News. 15 December 2003. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ↑ X, Malcolm; Breitman, George (1970). By Any Means Necessary: Speeches, Interviews and a Letter by Malcolm X. Pathfinder Press. ISBN 0-87348-145-3.

- ↑ "Cocktail-Rezept: Lumumba". Onlinebar.de. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ↑ "Done Too Soon" lyrics

Sources

- Mahoney, Richard D. JFK: Ordeal in Africa. Oxford University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-19-503341-8

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Patrice Lumumba |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Patrice Lumumba. |

- Speeches and writings by and about Patrice Lumumba, at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- Virtual Memorial to Patrice Lumumba, at Find-A-grave.

- Patrice Lumumba: 50 Years Later, Remembering the U.S.-Backed Assassination – video report by Democracy Now!

- SpyCast – 1 December 2007: On Assignment to Congo-Peter chats with Larry Devlin, the CIA's legendary station chief in Congo during the 1960s.

- Africa Within. A rich source of information on Lumumba, including a reprint of Stephen R. Weissman's 21 July 2002 article from the Washington Post.

- Patrice Lumumba at Find a Grave

- BBC Lumumba apology: Congo's mixed feelings.

- Mysteries of History Lumumba assassination.

- Lumumba and the Congo Documentary of Lumumba's life and work in the Congo.

- BBC An "On this day" text. It features an audio clip of a BBC correspondent on Lumumba's death.

- Belgian Parliament The findings of the Belgian Commission of 2001 investigating Belgian involvement in the death of Lumumba. Documents at the bottom of the page are in English.

- Beat Knowledge tribute to Lumumba Tribute to Lumumba on 50th anniversary of his assassination (17 January 2011).

- Belgian Commission's Conclusion A particular document from the previous link.

- D'Lynn Waldron Dr. D'Lynn Waldron's extensive archive of articles, photographs, and documents from her days as a foreign press correspondent in Lumumba's 1960 Congo.

- CIA plans included the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, report from the Washington Post by Karen DeYoung and Walter Pincus.

- Patrice Emery Lumumba: Memory of Congolese Leader Lives on 50 Years Later.

- David Akerman (21 October 2000). "Who Killed Lumumba?". BBC. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- Harry Gilroy (1 July 1960). "Lumumba Assails Colonialism as Congo Is Freed". New York Times. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- "The Bad Dream". Time Magazine. 20 January 1961. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- "Lumumba children get gifts from Germany". The Straits Times. 13 February 1961. Retrieved 8 October 2010. ( Picture of Lumumba's children in Egypt, visited by the wife of East Germany's leading foreign politician Heinrich Rau. )

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Position created on independence from Belgium |

Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo 24 June 1960 – 5 September 1960 |

Succeeded by Joseph Ileo |

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

|