Patio process

The patio process was a process used to extract silver from ore. The process was invented by Bartolomé de Medina in Pachuca, New Spain (Mexico), in 1554.[1] The patio process was the first process to use mercury amalgamation to recover silver from ore. It replaced smelting as the primary method of extracting silver from ore at Spanish colonies in the Americas. Other amalgamation processes were later developed, importantly the pan amalgamation process, and its variant, the Washoe process. The silver separation process generally differed from gold parting and gold extraction, although amalgamation with mercury was also sometimes used to extract gold.

Development of the patio process

Bartolomé de Medina was a successful Spanish merchant who became fascinated with the problem of decreasing silver yields from ores mined in Spanish America. By the mid-sixteenth century, it was well known in Spain that American silver production was in decline due to the depletion of high-grade ores and increasing production costs. The New Laws, prohibiting the enslavement of Indians, had resulted in higher labor costs as miners turned to wage labor and expensive African slaves. These higher production costs made mining and smelting anything but the highest grade silver ores prohibitively expensive, just as the availability of high grade ores was in decline.[2] Bartolomé de Medina initially focused his attentions on learning about new smelting methods from smelters in Spain. He was approached during his research by an unknown German man, known only as "Maestro Lorenzo," who told him that silver could be extracted from ground ores using mercury and a salt-water brine.[3] With this knowledge, Medina left Spain for New Spain (Mexico) in 1554 and established a model patio refinery in order to prove the effectiveness of the new technology. Medina is generally credited with adding "magistral" (a copper sulfate) to the mercury and salt-water solution in order to catalyze the amalgamation reaction.[4] However, some historians assert that there were already sufficient copper sulfates in the local ores and that no additional magistral was needed.[5] Regardless of whether or not Medina's contribution was entirely original, he promoted his process to local miners and was able to obtain a patent from the Viceroy of New Spain. As a result, he is generally credited with the invention of silver amalgamation in the form of the patio process.[6]

Basic elements of the patio process

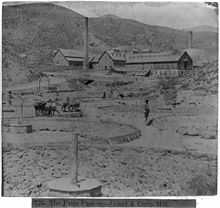

Silver ores were crushed (typically either in "arrastras" or stamp mills) to a fine slime which was mixed with salt, water, magistral (essentially an impure form of copper sulfate), and mercury, and spread in a 1-to-2-foot-thick (0.30 to 0.61 m) layer in a patio, (a shallow-walled, open enclosure). Horses were driven around on the patio to further mix the ingredients. After weeks of mixing and soaking in the sun, a complex reaction converted the silver to native metal, which formed an amalgam with the mercury and was recovered.[7] The amount of salt and copper sulfate varied from one-quarter to ten pounds of one or the other, or both, per ton of ore treated. The decision of how much of each ingredient to add, how much mixing was needed, and when to halt the process depended on the skill of an azoguero (English: quicksilver man). The loss of mercury in amalgamation processes is generally one to two times the weight of silver recovered.[8]

The patio process was the first form of amalgamation. However, it is unclear whether this process or a similar process—in which amalgamation occurred in heated vats rather than open patios—was the predominant form of amalgamation in New Spain, as the earliest known illustration of the patio process dates from 1761. There is substantial evidence that both processes were used from an early date in New Spain, while open patios were never adopted in Peru.[9] Both processes required that ore be crushed and refiners quickly established mills to process ore once amalgamation was introduced. By the seventeenth century, water-powered mills became dominant in both New Spain and Peru.[10]

Due to amalgamation's reliance upon mercury, an expansion of mercury production was central to the expansion of silver production. From shortly after the invention of mercury amalgamation to the end of the colonial period, the Spanish crown maintained a monopoly on mercury production and distribution, ensuring a steady supply of royal income. Fluctuations in mercury prices generally resulted in corresponding increases and decreases in silver production.[11]

Broader historical significance

The introduction of amalgamation to silver refining in the Americas not only ended the mid-sixteenth century crisis in silver production, it also inaugurated a rapid expansion of silver production in New Spain and Peru as miners could now profitably mine lower-grade ores. As a result of this expansion, the Americas became the primary producer of the world's silver, with Spanish America producing three-fifths of the world's silver supply prior to 1900.[12]

While a number of factors resulted in the minimal use of forced Indian labor in Mexican silver production,[13] the introduction of silver amalgamation allowed for an expansion of silver production in Peru that had profound consequences for Peru's native population. Francisco Toledo, the Viceroy of Peru in the 1570s, saw amalgamation as the key to expanding Peruvian silver production. He encouraged miners to adopt amalgamation and construct mercury mines. More significantly, in order to provide sufficient labor to accommodate the expansion of silver mining to lower-grade ores, Toledo organized an Indian draft labor system, the mita.[14] Under this system, thousands of natives were forced to work in silver and mercury mines for less than subsistence-level wages. Twelve thousand draft laborers regularly worked at the largest mine in the Americas, located at Potosí in modern Bolivia. Native attempts to avoid the mita led to the abandonment of many Indian villages throughout Peru.[15] Spanish monopolization of refining through amalgamation cut natives out of what had earlier been a native-dominated enterprise. Refining represented the most profitable segment of silver production. In conjunction with the mita, the exclusion of natives from owning refineries contributed to the transformation of Peruvian natives into a poorly paid labor force.[16]

The rapid expansion of silver production and coinage—made possible due to the invention of amalgamation—has often been identified as the primary driver of the price revolution, a period of high inflation lasting from the sixteenth to early seventeenth-century in Europe. Proponents of this theory argue that Spain's reliance on silver coins from the Americas to finance its large balance of payments deficits resulted in a general expansion of the European money supply and corresponding inflation. Critics of the theory, however, argue that inflation was really a result of European government policies and population growth.[17]

While the role of the expansion in silver production in the price revolution may be disputed, this expansion is often acknowledged as a key ingredient in the formation of early-modern world trade. Spanish American production fed Chinese demand for silver, facilitating the development of extensive trade networks linking Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas as Europeans sought to gain access to Chinese wares.[18]

References

- ↑ Alan Probert, "Bartolomé de Medina: The Patio Process and the Sixteenth Century Silver Crisis" in Bakewell, Peter, ed. Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Variorum: Brookfield, 1997, p. 96.

- ↑ Alan Probert, "Bartolomé de Medina: The Patio Process and the Sixteenth Century Silver Crisis" in Bakewell, Peter, ed. Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Variorum: Brookfield, 1997, p.102.

- ↑ Alan Probert, "Bartolomé de Medina: The Patio Process and the Sixteenth Century Silver Crisis" in Bakewell, Peter, ed. Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Variorum: Brookfield, 1997, p.107.

- ↑ Alan Probert, "Bartolomé de Medina: The Patio Process and the Sixteenth Century Silver Crisis" in Bakewell, Peter, ed. Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Variorum: Brookfield, 1997, p.109-111.

- ↑ D. A. Brading and Harry E. Cross, "Colonial Silver Mining: Mexico and Peru", The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 52, No. 4 (November 1972), pp. 545-579.

- ↑ Probert, 110-112.

- ↑ W.H. Dennis (1963) 100 Years of Metallurgy, Chicago: Aldine

- ↑ Egleston, Thomas (1883). "The Patio and Cazo Process of Amalgamating Silver Ores.". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 3 (1): 1–66.

- ↑ Brading and Cross, 553-554.

- ↑ Probert, 112; Peter Bakewell, "Technological Change in Potosí: The Silver Boom of the 1570's," in Bakewell, Peter, ed. Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Variorum: Brookfield, 1997, pp. 91-92.

- ↑ Brading and Cross, 562.

- ↑ Probert, 97.

- ↑ Brading and Cross, 557.

- ↑ Bakewell, 76, 81.

- ↑ Brading and Cross, 559.

- ↑ Bakewell, 95.

- ↑ Douglas Fisher, "The Price Revolution: A Monetary Interpretation," The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 49, No. 4 (Dec. 1989), 883-884.

- ↑ Dennis Flynn and Arturo Giráldez, "Born with a 'Silver Spoon': The Origin of World Trade in 1571," Journal of World History, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Fall, 1995), 202-203.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||