Particle physics experiments

Particle physics experiments briefly discusses a number of past, present, and proposed experiments with particle accelerators, throughout the world. In addition, some important accelerator interactions are discussed. Also, some notable systems components are discussed, named by project.

AEGIS (particle physics)

AEGIS is a proposed experiment to be set up at the Antiproton Decelerator at CERN. In addition, AEGIS is an acronym for: Antimatter Experiment: Gravity, Interferometry, Spectroscopy)

The proposed experiment:

It would attempt to determine if gravity affects antimatter in the same way it affects matter by testing its effect on an antihydrogen beam. By sending a stream of antihydrogen through a series of diffraction gratings, the pattern of light and dark patterns would allegedly enable the position of the beam to be pinpointed with up to 1% accuracy.[1]

Athena

ATHENA was an antimatter research project that took place at the AD Ring at CERN. In 2005 ATHENA was disbanded and many of the former members became the ALPHA Collaboration. In August 2002, it was the first experiment to produce 50,000 low-energy antihydrogen atoms, as reported in the journal Nature.[2][3]

For antihydrogen to be created, antiprotons and positrons must first be prepared. Once the antihydrogen is created, a high-resolution detector is needed to confirm that the antihydrogen was created, as well as to look at the spectrum of the antihydrogen in order to compare it to "normal" hydrogen.[4]

The antiprotons are obtained from CERN's Antiproton Decelerator while the positrons are obtained from a positron accumulator. The antiparticles are then led into a recombination trap to create antihydrogen. The trap is surrounded by the ATHENA detector, which detects the annihilation of the antiprotons as well as the positrons.

The ATHENA Collaboration comprised the following institutions[5]

- University of Aarhus, Denmark

- University of Brescia, Italy

- CERN

- University of Genoa, Italy

- University of Pavia, Italy

- RIKEN, Japan

- Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- University of Wales Swansea, United Kingdom

- University of Tokyo, Japan

- University of Zurich, Switzerland

- National Institute for Nuclear Physics, Italy

ARGUS (experiment)

The ARGUS experiment was a particle physics experiment that ran at the electron-positron collider ring DORIS II at DESY. It is the first experiment that observed the mixing of the B mesons (in 1987)[6]

The ARGUS detector was a hermetic detector with 90% coverage of the full solid angle. It had drift chambers, a time-of-flight system, an electromagnetic calorimeter and a muon chamber system.[7]

In physics, the ARGUS distribution, named after this experiment,[8] is the probability distribution of the reconstructed invariant mass of a decayed particle candidate in continuum background. Its probability density function (not normalized) is:

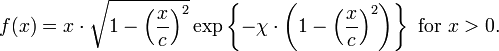

Sometimes a more general form is used to describe a more peaking-like distribution:

Here parameters c, χ, p represent the cutoff, curvature, and power (p = 0.5 gives a regular ARGUS) respectively.

ATRAP

The ATRAP collaboration at CERN developed out of TRAP, a collaboration whose members pioneered cold antiprotons, cold positrons, and first made the ingredients of cold antihydrogen to interact. ATRAP members also pioneered accurate hydrogen spectroscopy and first observed hot antihydrogen atoms. The collaboration includes investigators from Harvard, the University of Bonn, the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics, the University of Amsterdam, York University, Seoul National University, NIST, Forschungszentrum Jülich.

Belle experiment

The Belle experiment is a particle physics experiment conducted by the Belle Collaboration, an international collaboration of more than 400 physicists and engineers investigating CP-violation effects at the High Energy Accelerator Research Organisation (KEK) in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan.

Systems components

ASTRID particle storage ring

ASTRID is a particle storage ring at the University of Aarhus, Århus, Denmark. It is located in the lower levels of the University of Aarhus Department of Physics and Astronomy.

Its construction was announced on 18 September 1987.[9] By 1998, it had been improved several times, notably increasing its maximum operation time to 30–35 hours.[10] In December 2008, a contract was awarded to design and build ASTRID 2, which will be built adjacent to ASTRID. ASTRID will be used to "top up" the new ring, allowing ASTRID 2 to operate nearly continuously.[11]

ASTRID 2 particle storage ring

ASTRID 2 will be a 46 meter particle storage ring at the University of Aarhus, Århus, Denmark.The contract to build the ring was awarded in December, 2008, and plans are expected to be complete by the end of 2009. It will be built in the lower levels of the University of Aarhus Department of Physics and Astronomy, adjacent to the existing ASTRID particle storage ring. Rather than having an electron beam which decays over time, it will be continually "topped up" by a feed from ASTRID, allowing nearly constant current.[11] It will generate synchrotron radiation to provide a tunable beam of light, expected to be of "remarkable" quality, with wavelengths from the ultraviolet through x-rays.[11]

Anti-proton deccelerator

The Antiproton Decelerator (AD) is a storage ring at the CERN laboratory in Geneva. The decelerated antiprotons are ejected to one of the connected experiments.

Current experiments

| Expt. | Acronym | Full name |

|---|---|---|

| AD-2 | ATRAP | Anti-hydrogen Trap Collaboration |

| AD-3 | ASACUSA | Atomic Spectroscopy And Collisions Using Slow Anti-protons |

| AD-4 | ACE | Anti-proton Cell Experiment |

| AD-5 | ALPHA | Anti-hydrogen Laser Physics Apparatus |

| AD-6 | AEGIS | Anti-hydrogen Experiment: Gravity, Interferometry, Spectroscopy |

Former experiments:

| Expt. | Acronym | Full name |

|---|---|---|

| AD-1 | ATHENA | ApparaTus for High-precision Experiments on Neutral Antimatter |

Accelerator interaction overview

Absorber

In high energy physics experiments, an absorber is a block of material used to absorb some of the energy of an incident particle. Absorbers can be made of a variety of materials, depending on the purpose; lead and liquid hydrogen are common choices.

Most absorbers are used as part of a detector.

A more recent use for absorbers is for ionization cooling, as in the International Muon Ionization Cooling Experiment.

In solar power, the most important part of the collector takes up the heat of the solar radiation through a medium (water + antifreeze). This is heated and circulates between the collector and the storage tank. A high degree of efficiency is achieved by using black absorbers or, even better, through selective coating.

In sunscreen, ingredients which absorb UVA/UVB rays, such as avobenzone and octyl methoxycinnamate, are known as absorbers. They are contrasted with physical "blockers" of UV radiation such as titanium dioxide and zinc oxide.

Accelerator physics

Accelerator physics is an interdisciplinary topic of applied physics, commonly defined by the intent of designing, building and operating particle accelerators.

The experiments conducted with particle accelerators are not regarded as part of accelerator physics, but belong (according to the objectives of the experiments) to e.g. particle physics, nuclear physics, condensed matter physics or materials physics. The types of experiments done at a particular accelerator facility are determined by characteristics of the generated particle beam such as average energy, particle type, intensity, and dimensions.

Event reconstruction

In a particle detector experiment, event reconstruction is the process of interpreting the electronic signals produced by the detector to determine the original particles that passed through, their momenta, directions, and the primary vertex of the event. Thus the initial physical process that occurred at the interaction point of the particle accelerator, whose study is the ultimate goal of the experiment, can be determined. The total event reconstruction is rarely possible (and rarely necessary); usually, only some part of the data described above is obtained and processed.

See also

- ALPHA Collaboration

- Antimatter

- CERN

- List of synchrotron radiation facilities

- Gravitational interaction of antimatter

- Particle physics

References

- ↑ Courtland, R. (12 June 2008). "Would an antimatter apple fall up?". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ "Thousands of cold anti-atoms produced at CERN" (Press release). CERN. 19 September 2002. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ↑ Amoretti, M.; et al. (2002). "Production and detection of cold antihydrogen atoms". Nature 419 (6906): 456. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..456A. doi:10.1038/nature01096. PMID 12368849.

- ↑ "How the ATHENA Experiment works". ATHENA. 14 September 2002. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ↑ "The ATHENA Collaboration". ATHENA. 30 January 2006. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ↑ Albrecht, H.; et al. (ARGUS Collaboration) (1987). "Observation of B0–B0 mixing". Physics Letters B 192 (1–2): 245. Bibcode:1987PhLB..192..245A. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(87)91177-4.

- ↑ Albrecht, H.; et al. (ARGUS Collaboration) (1989). "Argus: A universal detector at DORIS II". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A 275 (1): 1–48. Bibcode:1989NIMPA.275....1A. doi:10.1016/0168-9002(89)90334-3.

- ↑ Albretch, H.; et al. (ARGUS Collaboration) (1990). "Search for hadronic b→u decays". Physics Letters B 241 (2): 278. Bibcode:1990PhLB..241..278A. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(90)91293-K. The function has been defined with parameter c representing the beam energy and parameter p set to 0.5. The normalization and the parameter χ have been obtained from data.

- ↑ Stensgaard, R. (1988). "ASTRID - The Aarhus Storage Ring". Physica Scripta 1988 (T22): 315. Bibcode:1988PhST...22..315S. doi:10.1088/0031-8949/1988/T22/051.

- ↑ Nielsen, J. S.; Møller, S. P. (1998). "New Developments at the ASTRID storage ring". Proceedings from 6th European Particle Accelerator Conference. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "ASTRID2 – the ultimate synchrotron radiation source". ASTRID. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

Further reading

- AEGIS collaboration (8 June 2007). "Proposal for the AEGIS experiment at the CERN Antiproton Decelerator". CERN.

- Testera, G.; et al. (2008). "Formation of a cold antihydrogen beam in AEGIS for gravity measurements". AIP Conference Proceedings 1037: 5–15. arXiv:0805.4727. Bibcode:2008AIPC.1037....5T. doi:10.1063/1.2977857.

External links

| Look up particle physics experiments in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- ANSTO website

- ANTARES website

- Antiproton Decelerator website

- ARGUS Fest

- ASTRID website

- ASTRID 2 website

- ATHENA website

- CERN's public site

- CERN Antimatter page

- National Medical Cyclotron website

![f(x)=x\cdot \left[1-\left({\frac {x}{c}}\right)^{2}\right]^{p}\exp \left\{-\chi \cdot \left(1-\left({\frac {x}{c}}\right)^{2}\right)\right\}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/d/b/0/9/db09743f0551db5d7819228ae1985c5b.png)