Pacific Ocean

|

| Earth's oceans |

|---|

|

World Ocean |

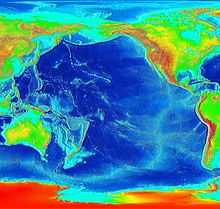

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.

At 165.25 million square kilometres (63.8 million square miles) in area, this largest division of the World Ocean – and, in turn, the hydrosphere – covers about 46% of the Earth's water surface and about one-third of its total surface area, making it larger than all of the Earth's land area combined.[2] The equator subdivides it into the North Pacific Ocean and South Pacific Ocean, with two exceptions: the Galápagos and Gilbert Islands, while straddling the equator, are deemed wholly within the South Pacific.[3] The Mariana Trench in the western North Pacific is the deepest point in the world, reaching a depth of 10,911 metres (35,797 ft).[4]

The eastern Pacific Ocean was first sighted by Europeans in the early 16th century when Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama in 1513 and discovered the great "southern sea" which he named Mar del Sur. The ocean's current name was coined by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan during the Spanish expedition of the world in 1521, as he encountered favourable winds on reaching the ocean. He therefore called it Mar Pacifico in Portuguese, meaning "peaceful sea".[5]

History

Important human migrations occurred in the Pacific in prehistoric times, most notably those of the Polynesians from the Asian edge of the ocean to Tahiti, Hawaii, New Zealand, Easter Island and possibly even America.[6]

The east side of the ocean was discovered by Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa in the early 16th century. Balboa's expedition crossed the Isthmus of Panama and reached the Pacific Ocean in 1513.[7] He named it Mar del Sur (South Sea). Later, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan sailed the Pacific on a Spanish expedition of world circumnavigation from 1519 to 1522. Magellan called the ocean Pacífico or "Pacific" ( that meant peaceful) because, after sailing through the stormy seas off Cape Horn, he was surprised how calm the waters became. Although Magellan himself died in the Philippines in 1521, Spanish navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano led the expedition back to Spain across the Indian Ocean and round the Cape of Good Hope, completing the first world circumnavigation in 1522.[8]

In 1564, five Spanish ships consisting of 379 explorers crossed the ocean from Mexico led by Miguel López de Legazpi and sailed to the Philippines and Mariana Islands.[9] For the remainder of the 16th century, Spanish influence was paramount, with ships sailing from Mexico and Peru across the Pacific Ocean to the Philippines, via Guam, and establishing the Spanish East Indies. The Manila galleons operated for two and a half centuries linking Manila and Acapulco, in one of the longest trade routes in history. Spanish expeditions also discovered Tuvalu, the Marquesas, the Solomon Islands and New Guinea in the South Pacific.

Later, in the quest for Terra Australis, Spanish explorers in the 17th century discovered the Pitcairn and Vanuatu archipelagos, and sailed the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea, named after navigator Luís Vaz de Torres. Dutch explorers, sailing around southern Africa, also engaged in discovery and trade; Abel Janszoon Tasman discovered Tasmania and New Zealand in 1642.[10] The 18th century marked the beginning of major exploration by the Russians in Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. Spain also sent expeditions to the Pacific Northwest reaching Vancouver Island in southern Canada, and Alaska. The French explored and settled Polynesia, and the British made three voyages with James Cook to the South Pacific and Australia, Hawaii, and the North American Pacific Northwest. In 1768 Pierre-Antoine Véron, a young astronomer accompanying Louis Antoine de Bougainville on his voyage of exploration, established the width of the Pacific with precision for the first time in history.[11] One of the earliest voyages of scientific exploration was organized by Spain in the Malaspina Expedition of 1789-1794. It sailed vast areas of the Pacific, from Cape Horn to Alaska, Guam and the Philippines, New Zealand, Australia and the South Pacific.

.jpeg)

Growing imperialism during the 19th century resulted in the occupation of much of Oceania by other European powers, and later, Japan and United States. Significant contributions to oceanographic knowledge were made by the voyages of HMS Beagle in the 1830s, with Charles Darwin aboard; HMS Challenger during the 1870s; the USS Tuscarora (1873–76); and the German Gazelle (1874–76).

Although the United States gained control of Guam and the Philippines from Spain in 1898,[12] Japan controlled most of the western Pacific by 1914 and occupied many other islands during World War II. However, by the end of that war, Japan was defeated and the U.S. Pacific Fleet was the virtual master of the ocean. Since the end of World War II, many former colonies in the Pacific have become independent states.

Geography

The Pacific separates Asia and Australia from the Americas. It may be further subdivided by the equator into northern (North Pacific) and southern (South Pacific) portions. It extends from the Antarctic region in the South to the Arctic in the north.[2] The Pacific Ocean encompasses approximately one-third of the Earth's surface, having an area of 165.2 million square kilometres (63.8 million square miles) —significantly larger than Earth's entire landmass of some 150 million square kilometres (58 million square miles).[13]

Extending approximately 15,500 kilometres (9,600 mi) from the Bering Sea in the Arctic to the northern extent of the circumpolar Southern Ocean at 60°S (older definitions extend it to Antarctica's Ross Sea), the Pacific reaches its greatest east-west width at about 5°N latitude, where it stretches approximately 19,800 kilometres (12,300 mi) from Indonesia to the coast of Colombia – halfway across the world, and more than five times the diameter of the Moon.[14] The lowest known point on Earth—the Mariana Trench—lies 10,911 metres (35,797 ft or 5,966 fathoms) below sea level. Its average depth is 4,280 metres (14,040 ft or 2,333 fathoms).[2]

Due to the effects of plate tectonics, the Pacific Ocean is currently shrinking by roughly an inch per year (2–3 cm/yr) on three sides, roughly averaging 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) a year. By contrast, the Atlantic Ocean is increasing in size.[15][16]

Along the Pacific Ocean's irregular western margins lie many seas, the largest of which are the Celebes Sea, Coral Sea, East China Sea, Philippine Sea, Sea of Japan, South China Sea, Sulu Sea, Tasman Sea, and Yellow Sea. The Strait of Malacca joins the Pacific and the Indian Oceans on the west, and Drake Passage and the Strait of Magellan link the Pacific with the Atlantic Ocean on the east. To the north, the Bering Strait connects the Pacific with the Arctic Ocean.[17]

As the Pacific straddles the 180th meridian, the West Pacific (or western Pacific, near Asia) is in the Eastern Hemisphere, while the East Pacific (or eastern Pacific, near the Americas) is in the Western Hemisphere.[18]

For most of Magellan's voyage from the Strait of Magellan to the Philippines, the explorer indeed found the ocean peaceful. However, the Pacific is not always peaceful. Many tropical storms batter the islands of the Pacific.[19] The lands around the Pacific Rim are full of volcanoes and often affected by earthquakes.[20] Tsunamis, caused by underwater earthquakes, have devastated many islands and in some cases destroyed entire towns.[21]

Bordering countries and territories

Sovereign nations

Australia

Australia Brunei

Brunei Cambodia

Cambodia Canada

Canada Chile

Chile China

China Colombia

Colombia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Ecuador

Ecuador El Salvador

El Salvador Federated States of Micronesia

Federated States of Micronesia Fiji

Fiji Guatemala

Guatemala Honduras

Honduras Indonesia

Indonesia Japan

Japan Kiribati

Kiribati North Korea

North Korea South Korea

South Korea Malaysia

Malaysia Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Mexico

Mexico Nauru

Nauru New Zealand

New Zealand Nicaragua

Nicaragua Palau

Palau Panama

Panama Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea Peru

Peru Philippines

Philippines Russia

Russia Samoa

Samoa Singapore

Singapore Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands Taiwan1

Taiwan1 Thailand

Thailand Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste Tonga

Tonga Tuvalu

Tuvalu United States

United States Vanuatu

Vanuatu Vietnam

Vietnam

1 The status of Taiwan is disputed. For more information, see political status of Taiwan.

Territories

American Samoa (US)

American Samoa (US) Baker Island (US)

Baker Island (US) Cook Islands (New Zealand)

Cook Islands (New Zealand) Coral Sea Islands (Australia)

Coral Sea Islands (Australia) Easter Island (Chile)

Easter Island (Chile) French Polynesia (France)

French Polynesia (France) Guam (US)

Guam (US) Hong Kong (China)

Hong Kong (China) Howland Island (US)

Howland Island (US) Jarvis Island (US)

Jarvis Island (US) Johnston Island (US)

Johnston Island (US) Kingman Reef (US)

Kingman Reef (US) Macau (China)

Macau (China) Midway Atoll (US)

Midway Atoll (US) New Caledonia (France)

New Caledonia (France) Niue (New Zealand)

Niue (New Zealand) Norfolk Island (Australia)

Norfolk Island (Australia) Northern Mariana Islands (US)

Northern Mariana Islands (US) Palmyra Atoll (US)

Palmyra Atoll (US) Pitcairn Islands (UK)

Pitcairn Islands (UK) Tokelau (New Zealand)

Tokelau (New Zealand) Wallis and Futuna (France)

Wallis and Futuna (France) Wake Island (US)

Wake Island (US)

Landmasses and islands

The islands entirely within the Pacific Ocean can be divided into three main groups known as Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia. Micronesia, which lies north of the equator and west of the International Date Line, includes the Mariana Islands in the northwest, the Caroline Islands in the centre, the Marshall Islands to the west and the islands of Kiribati in the southwest.[22][23]

Melanesia, to the southwest, includes New Guinea, the world's second largest island after Greenland and by far the largest of the Pacific islands. The other main Melanesian groups from north to south are the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, Santa Cruz, Vanuatu, Fiji and New Caledonia.[24]

The largest area, Polynesia, stretching from Hawaii in the north to New Zealand in the south, also encompasses Tuvalu, Tokelau, Samoa, Tonga and the Kermadec Islands to the west, the Cook Islands, Society Islands and Austral Islands in the center, and the Marquesas Islands, Tuamotu, Mangareva Islands and Easter Island to the east.[25]

Islands in the Pacific Ocean are of four basic types: continental islands, high islands, coral reefs, and uplifted coral platforms. Continental islands lie outside the andesite line and include New Guinea, the islands of New Zealand, and the Philippines. Some of these islands are structurally associated with nearby continents. High islands are of volcanic origin, and many contain active volcanoes. Among these are Bougainville, Hawaii, and the Solomon Islands.[26]

The Coral reefs of the South Pacific are low-lying structures that have built up on basaltic lava flows under the ocean's surface. One of the most dramatic is the Great Barrier Reef off northeastern Australia with chains of reef patches. A second island type formed of coral is the uplifted coral platform, which is usually slightly larger than the low coral islands. Examples include Banaba (formerly Ocean Island) and Makatea in the Tuamotu group of French Polynesia.[27][28]

Water characteristics

The volume of the Pacific Ocean, representing about 50.1 percent of the world's oceanic water, has been estimated at some 714 million cubic kilometers.[29] Surface water temperatures in the Pacific can vary from −1.4 °C (29.5 °F), the freezing point of sea water, in the poleward areas to about 30 °C (86 °F) near the equator.[30] Salinity also varies latitudinally reaching a maximum of 37 parts per thousand in the southeastern area. The water near the equator, which can have a salinity as low as 34 parts per thousand, is less salty than that found in the mid-latitudes because of abundant equatorial precipitation throughout the year. The lowest counts of less than 32 parts per thousand are found in the far north as less evaporation of seawater takes place in these frigid areas.[31] The motion of Pacific waters is generally clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere (the North Pacific gyre) and counter-clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. The North Equatorial Current, driven westward along latitude 15°N by the trade winds, turns north near the Philippines to become the warm Japan or Kuroshio Current.[32]

Turning eastward at about 45°N, the Kuroshio forks and some water moves northward as the Aleutian Current, while the rest turns southward to rejoin the North Equatorial Current.[33] The Aleutian Current branches as it approaches North America and forms the base of a counter-clockwise circulation in the Bering Sea. Its southern arm becomes the chilled slow, south-flowing California Current.[34] The South Equatorial Current, flowing west along the equator, swings southward east of New Guinea, turns east at about 50°S, and joins the main westerly circulation of the Southern Pacific, which includes the Earth-circling Antarctic Circumpolar Current. As it approaches the Chilean coast, the South Equatorial Current divides; one branch flows around Cape Horn and the other turns north to form the Peru or Humboldt Current.[35]

Climate

The weather systems in the Northern and Southern hemispheres generally mirror each other. The trade winds in the southern and eastern Pacific are remarkably steady while conditions in the North Pacific are far more varied with, for example, cold winter temperatures on the east coast of Russia contrasting with the milder weather off British Columbia during the winter months.[36] Cyclones are liable to form south of Mexico, striking Central America between June and October, as well as in southeast and east Asia from May to December, especially in August and September. In the western Pacific, monsoons in the summer months contrast with dry winds in the winter which blow over the ocean from the Asian landmass. In the equatorial Pacific, El Niño, a band of warm ocean temperatures, affects weather conditions in the western Pacific. In the far north, icing from October to May can present a hazard for shipping while persistent fog occurs from June to December.[37]

Geology

The ocean was mapped by Abraham Ortelius; he called it Maris Pacifici because of Ferdinand Magellan, who sailed the Pacific during his circumnavigation from 1519 to 1522 and said that it was much more calm than the Atlantic.[38]

The andesite line is the most significant regional distinction in the Pacific. A petrologic boundary, separates the deeper, mafic igneous rock of the Central Pacific Basin from the partially submerged continental areas of felsic igneous rock on its margins.[39] The andesite line follows the western edge of the islands off California and passes south of the Aleutian arc, along the eastern edge of the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Kuril Islands, Japan, the Mariana Islands, the Solomon Islands, and New Zealand's North Island.[40][23]

The dissimilarity continues northeastward along the western edge of the Andes Cordillera along South America to Mexico, returning then to the islands off California. Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan, New Guinea, and New Zealand lie outside the andesite line.

Within the closed loop of the andesite line are most of the deep troughs, submerged volcanic mountains, and oceanic volcanic islands that characterize the Pacific basin. Here basaltic lavas gently flow out of rifts to build huge dome-shaped volcanic mountains whose eroded summits form island arcs, chains, and clusters. Outside the andesite line, volcanism is of the explosive type, and the Pacific Ring of Fire is the world's foremost belt of explosive volcanism.[22] The Ring of Fire is named after the several hundred active volcanoes that sit above the various subduction zones.

The Pacific Ocean is the only ocean which is almost totally bounded by subduction zones. Only the Antarctic and Australian coasts have no nearby subduction zones.

Geological history

The Pacific Ocean developed from the Panthalassa following the breakup of Pangaea. There is no firm date for when the changeover occurred, as the replacement of the sea bed is a continuous process, though reconstruction maps often change the name from Panthalassic to Pacific around the time the Atlantic Ocean began to open.[41] The Panthalassic Ocean first opened 750 million years ago at the breakup of Rodinia,[41] but the oldest Pacific Ocean floor is only around 180 Ma old.[42]

Seamount chains

The Pacific Ocean contains several long seamount chains, formed by hotspot volcanism. These include the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain and the Louisville seamount chain.

Economy

The exploitation of the Pacific's mineral wealth is hampered by the ocean's great depths. In shallow waters of the continental shelves off the coasts of Australia and New Zealand, petroleum and natural gas are extracted, and pearls are harvested along the coasts of Australia, Japan, Papua New Guinea, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Philippines, although in sharply declining volume in some cases.[43]

Fishing

Fish are an important economic asset in the Pacific. The shallower shoreline waters of the continents and the more temperate islands yield herring, salmon, sardines, snapper, swordfish, and tuna, as well as shellfish.[44] Overfishing has become a serious problem in some areas. For example, catches in the rich fishing grounds of the Okhotsk Sea off the Russian coast have been reduced by at least half since the 1990s as a result of overfishing.[45]

Environmental issues

The quantity of small plastic fragments floating in the north-east Pacific Ocean has increased a hundredfold over the past 40 years (2012).[46]

Marine pollution is a generic term for the harmful entry into the ocean of chemicals or particles. The main culprits are those using the rivers for disposing of their waste.[47] The rivers then empty into the Ocean, often also bringing chemicals used as fertilizers in agriculture. The excess of oxygen-depleting chemicals in the water leads to hypoxia and the creation of a dead zone.[48]

Marine debris, also known as marine litter, is human-created waste that has ended up floating in a lake, sea, ocean or waterway. Oceanic debris tends to accumulate at the centre of gyres and coastlines, frequently washing aground where it is known as beach litter.[47]

In addition, the Pacific Ocean has served as the crash site of satellites, including Mars 96, Fobos-Grunt and Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite.

Major ports and harbors

See also

References

- ↑ "Library Acquires Copy of 1507 Waldseemüller World Map - News Releases (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Pacific Ocean". Britannica Concise. 2006. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ↑ International Hydrographic Organization (1953). "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition". Monte Carlo, Monaco: International Hydrographic Organization. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ↑ "Japan Atlas: Japan Marine Science and Technology Center". Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Ferdinand Magellan". Newadvent.org. 1910-10-01. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ↑ Stanley, David (2004). South Pacific. David Stanley. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-56691-411-6. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Ober, Frederick Albion. Vasco Nuñez de Balboa. Library of Alexandria. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4655-7034-5. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Life in the sea: Pacific Ocean", Oceanário de Lisboa. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Henderson, James D.; Delpar, Helen; Brungardt, Maurice Philip; Weldon, Richard N. (January 2000). A Reference Guide to Latin American History. M.E. Sharpe. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-56324-744-6. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Primary Australian History: Book F [B6] Ages 10-11. R.I.C. Publications. 2008. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-74126-688-7. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Glyndwr (2004). Captain Cook: Explorations And Reassessments. Boydell Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-84383-100-6. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Tewari, Nita; Alvarez, Alvin N. (17 September 2008). Asian American Psychology: Current Perspectives. CRC Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-84169-749-9. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Area of Earth's Land Surface", The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Nuttall, Mark (2005). Encyclopedia of the Arctic: A-F. Routledge. p. 1461. ISBN 978-1-57958-436-8. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ "Plate Tectonics", Bucknell University. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Young, Greg (2009). Plate Tectonics. Capstone. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-7565-4232-0. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ International Hydrographic Organization (1953). Limits of Oceans and Seas. International Hydrographic Organization. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Agno, Lydia (1998). Basic Geography. Goodwill Trading Co., Inc. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-971-11-0165-7. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "Pacific Ocean: The trade winds", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Murphy, Shirley Rousseau (1979). The Ring of Fire. Avon. ISBN 978-0-380-47191-1. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Bryant, Edward (2008). Tsunami: The Underrated Hazard. Springer. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-3-540-74274-6. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Academic American encyclopedia. Grolier Incorporated. 1997. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7172-2068-7. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Lal, Brij Vilash; Fortune, Kate (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2265-1. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. pp. 521–. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Dunford, Betty; Ridgell, Reilly (1996). Pacific Neighbors: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. Bess Press. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-1-57306-022-6. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Gillespie, Rosemary G.; Clague, David A. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islands. University of California Press. p. 706. ISBN 978-0-520-25649-1. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Coral island", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "Nauru", Charting the Pacific. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "PWLF.org - The Pacific WildLife Foundation - The Pacific Ocean". Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ↑ Mongillo, John F. (2000). Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. University Rochester Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-1-57356-147-1. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "Pacific Ocean: Salinity", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "Wind Driven Surface Currents: Equatorial Currents Background", Ocean Motion. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "Kuroshio", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "Aleutian Current", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "South Equatorial Current", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "Pacific Ocean: Islands", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ "Pacific Ocean", World Factbook, CIA. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ Turnbull, Alexander (15 December 2006). Map New Zealand: 100 Magnificent Maps from the Collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library. Godwit. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-86962-126-1. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ Trent, D. D.; Hazlett, Richard; Bierman, Paul (2010). Geology and the Environment. Cengage Learning. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-538-73755-5. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ Mueller-Dombois, Dieter (1998). Vegetation of the Tropical Pacific Islands. Springer. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-387-98313-4. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "GEOL 102 The Proterozoic Eon II: Rodinia and Pannotia". Geol.umd.edu. 2010-01-05. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ↑ Mussett, Alan E.; Khan, M. Aftab (23 October 2000). Looking Into the Earth: An Introduction to Geological Geophysics. Cambridge University Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-521-78574-7. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ "Pacific Ocean: Fisheries", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Pacific Ocean: Commerce and Shipping", The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th edition. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "Pacific Ocean Threats & Impacts: Overfishing and Exploitation", Center for Ocean Solutions. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Plastic waste in the North Pacific is an ongoing concern BBC 9 May 2012

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 "PHOTOS: Giant Ocean-Trash Vortex Documented-A First". News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ↑ Gerlach: Marine Pollution, Springer, Berlin (1975)

Further reading

- Barkley, Richard A. (1968). Oceanographic Atlas of the Pacific Ocean. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- prepared by the Special Publications Division, National Geographic Society. (1985). Blue Horizons: Paradise Isles of the Pacific. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-87044-544-8.

- Cameron, Ian (1987). Lost Paradise: The Exploration of the Pacific. Topsfield, Mass.: Salem House. ISBN 0-88162-275-3.

- Couper, A. D. (ed.) (1989). Development and Social Change in the Pacific Islands. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00917-0.

- Gilbert, John (1971). Charting the Vast Pacific. London: Aldus. ISBN 0-490-00226-9.

- Igler, David (2013). The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-199-91495-8.

- Lower, J. Arthur (1978). Ocean of Destiny: A Concise History of the North Pacific, 1500-1978. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0101-8.

- Napier, W.; Gilbert, J., and Holland, J. (1973). Pacific Voyages. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04335-X.

- Nunn, Patrick D. (1998). Pacific Island Landscapes: Landscape and Geological Development of Southwest Pacific Islands, Especially Fiji, Samoa and Tonga. editorips@usp.ac.fj. ISBN 978-982-02-0129-3.

- Oliver, Douglas L. (1989). The Pacific Islands (3rd ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1233-6.

- Ridgell, Reilly (1988). Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia (2nd ed.). Honolulu: Bess Press. ISBN 0-935848-50-9.

- Soule, Gardner (1970). The Greatest Depths: Probing the Seas to 20,000 feet (6,100 m) and Below. Philadelphia: Macrae Smith. ISBN 0-8255-8350-0.

- Spate, O. H. K. (1988). Paradise Found and Lost. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1715-5.

- Terrell, John (1986). Prehistory in the Pacific Islands: A Study of Variation in Language, Customs, and Human Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30604-3.

External links

| Look up pacific ocean in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pacific Ocean. |

- EPIC Pacific Ocean Data Collection Viewable on-line collection of observational data

- NOAA In-situ Ocean Data Viewer plot and download ocean observations

- NOAA PMEL Argo profiling floats Realtime Pacific Ocean data

- NOAA TAO El Niño data Realtime Pacific Ocean El Niño buoy data

- NOAA Ocean Surface Current Analyses – Realtime (OSCAR) Near-realtime Pacific Ocean Surface Currents derived from satellite altimeter and scatterometer data

Coordinates: 0°N 160°W / 0°N 160°W

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||