PUREX

PUREX is a chemical method used to purify fuel for nuclear reactors or nuclear weapons. It is an acronym standing for Plutonium Uranium Redox EXtraction.[1] PUREX is the de facto standard aqueous nuclear reprocessing method for the recovery of uranium and plutonium from used ("spent", or "depleted") nuclear fuel. It is based on liquid–liquid extraction ion-exchange.

The PUREX process was invented by Herbert H. Anderson and Larned B. Asprey at the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, as part of the Manhattan Project under Glenn T. Seaborg; their patent "Solvent Extraction Process for Plutonium" filed in 1947,[2] mentions tributyl phosphate as the major reactant which accomplishes the bulk of the chemical extraction.[3]

Overview

The spent nuclear fuel to which this process is applied consists primarily of certain very high atomic-weight (actinoid or "actinide") elements (e.g., uranium) along with smaller amounts of material composed of lighter atoms, notably the so-called fission products.

The actinoid elements in this case consist primarily of the largely unconsumed remains of the original fuel (typically U-238 and other isotopes of uranium). In addition there are smaller quantities of other actinoids, created when one isotope is transmuted into another by a reaction involving neutron capture. Plutonium-239 is the leading example. Another term sometimes seen in relation to this secondary material (and other material produced similarly) is activation products.

In response to the PUREX process' ability to extract nuclear weapons materials from the spent fuel, trade in the relevant chemicals is monitored.

In brief, the PUREX process is a liquid-liquid extraction ion-exchange method used to reprocess spent nuclear fuel, in order to extract primarily uranium and plutonium, independent of each other, from the other constituents.

Chemical process

The irradiated fuel is first dissolved in nitric acid at a concentration of ca. 7 M. After the dissolution step it is normal to remove the fine insoluble solids, because otherwise they will disturb the solvent extraction process by altering the liquid-liquid interface. It is known that the presence of a fine solid can stabilize an emulsion. Emulsions are often referred to as third phases in the solvent extraction community.

An organic solvent composed of 30% tributyl phosphate (TBP) in a hydrocarbon solvent, such as kerosene, is used to extract the uranium as UO2(NO3)2·2TBP complexes, and plutonium as similar complexes, from other fission products, which remain in the aqueous phase. The transuranium elements americium and curium also remain in the aqueous phase. The nature of the organic soluble uranium complex has been the subject of some research. A series of complexes of uranium with nitrate and trialkyl phosphates and phosphine oxides have been characterized.[4]

Plutonium is separated from uranium by treating the kerosene solution with aqueous ferrous sulphamate, which selectively reduces the plutonium to the +3 oxidation state. The plutonium passes into the aqueous phase. The uranium is stripped from the kerosene solution by back-extraction into nitric acid at a concentration of ca. 0.2 mol dm−3.[5]

Degradation products of TBP

It is normal to extract both the uranium and plutonium from the majority of the fission products, but it is not possible to get an acceptable separation of the fission products from the actinide products with a single extraction cycle. The unavoidable irradiation (by the material being processed) of the tributyl phosphate / hydrocarbon mixture produces dibutyl hydrogen phosphate. This degradation product is able to act as an extraction agent for many metals, hence leading to the contamination of the product by fission products. Hence it is normal to use more than one extraction cycle. The first cycle lowers the radioactivity of the mixture, allowing the later extraction cycles to be kept cleaner in terms of degradation products.

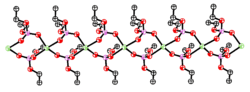

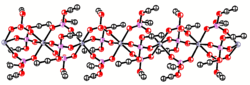

Dialkyl hydrogen phosphates are able to form complexes with many metals. These include some polymeric metal complexes. Formation of these coordination polymers is one way in which fine solids can be formed in the process. While the cadmium concentration in both the fuel dissolution liquor and the PUREX raffinate is very low, the polymeric complex of cadmium of diethyl phosphate is shown in the left image. The right one is the structure of a lanthanide complex of diethyl phosphate. Unlike cadmium the concentration of neodymium in these mixtures formed from fuel is very high.

-

This complex is formed from cadmium ions and diethyl phosphate ions

-

This complex is formed from neodymium ions and diethyl phosphate

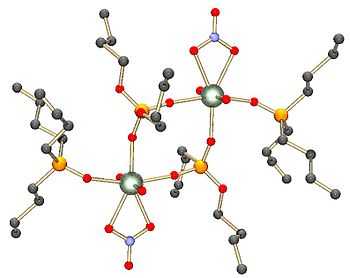

Below is a mixed tributyl phosphate dibutyl phosphate complex of uranium. Because the dibutyl phosphate ligands are acidic, it will now be possible to extract uranium by an ion exchange liquid-liquid extraction mechanism rather than only by a solvation mechanism. This will potentially make the stripping of uranium with dilute nitric acid less effective.

Extraction of technetium

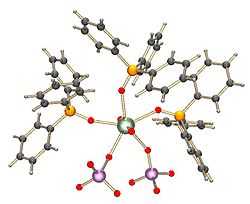

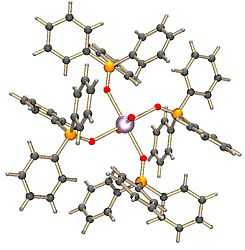

In addition, the uranium(VI) tributyl phosphate system is able to extract technetium as pertechnetate through an ion pair extraction mechanism. Here is an example of a rhenium version of a uranium / technetium complex which is thought to be responsible for the extraction of technetium into the organic phase. Here are two pictures of actinyl complexes of triphenylphosphine oxide which have been crystallised with perrhenate. With the less highly charged neptunyl ion it is also possible to form a complex.[6]

-

This complex is formed from a uranyl ion and three molecules of triphenylphosphine oxide. The anions are in the first coordination sphere of the metal

-

This complex is formed from a neptunyl ion and four molecules of triphenylphosphine oxide. The anions are separated from the metal center

Pollution

The PUREX Plant at the Hanford Site was responsible for producing 'copious volumes of liquid wastes', resulting in the radioactive contamination of groundwater.[7] A U.S. government report released in 1992 estimated that 685,000 curies (25.3 PBq) of radioactive iodine-131 had been released into the river and air from the Hanford site between 1944 and 1947. Clean up costs are an estimated $2 billion a year.[8]

List of nuclear reprocessing sites

- COGEMA La Hague site

- Mayak

- Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant and B205 at Sellafield

- Tokai, Ibaraki

- West Valley Reprocessing Plant

- Savannah River Site

- Idaho Chemical Processing Plant, (now Idaho National Laboratory)

- Radiochemical Engineering Development Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

See also

- Nuclear fuel cycle

- Nuclear breeder reactor

- Spent nuclear fuel shipping cask

- Global Nuclear Energy Partnership announced February, 2006

References & notes

- ↑ Gregory Choppin, Jan-Olov Liljenzin, Jan Rydberg. "Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry, Third Edition". p. 610. ISBN 978-0-7506-7463-8.

- ↑ US patent 2924506, Anderson, Herbert H. and Asprey, Larned B. & Asprey, Larned B., "Solvent extraction process for plutonium", issued 1960-02-09

- ↑ P. Gary Eller, Bob Penneman, and Bob Ryan (1st quarter 2005). "Pioneer actinide chemist Larned Asprey dies". The Actinide Research Quarterly. Los Alamos National Laboratory. pp. 13–17.

- ↑ J.H. Burns (1983). "Solvent-extraction complexes of the uranyl ion. 2. Crystal and molecular structures of catena-bis(.mu.-di-n-butyl phosphato-O,O')dioxouranium(VI) and bis(.mu.-di-n-butyl phosphato-O,O')bis[(nitrato)(tri-n-butylphosphine oxide)dioxouranium(VI)]". Inorganic Chemistry 22 (8): 1174. doi:10.1021/ic00150a006.

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1261. ISBN 0080379419.

- ↑ G.H. John, I. May, M.J. Sarsfield, H.M. Steele, D. Collison, M. Helliwell and J.D. McKinney (2004). "The structural and spectroscopic characterisation of three actinyl complexes with coordinated and uncoordinated perrhenate .". Dalton Trans. (5): 734. doi:10.1039/b313045b.

- ↑ Gerber, M.S. (February 2001). "History of Hanford Site Defense Production (Brief)". Fluor Hanford / US DOE. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ Martin, Hugo (August 13, 2008). "Nuclear site now a tourist hot spot". The Los Angeles Times.

Further reading

- OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, The Economics of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle, Paris, 1994

- I. Hensing and W Schultz, Economic Comparison of Nuclear Fuel Cycle Options, Energiewirtschaftlichen Instituts, Cologne, 1995.

- Cogema, Reprocessing-Recycling: the Industrial Stakes, presentation to the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Bonn, 9 May 1995.

- OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, Plutonium Fuel: An Assessment, Paris, 1989.

- National Research Council, "Nuclear Wastes: Technologies for Separation and Transmutation", National Academy Press, Washington D.C. 1996.

External links

- Processing of Used Nuclear Fuel, World Nuclear Association

- Reactor-Grade Plutonium and Development of Nuclear Weapons, Analytical Center for Non-proliferation

- PUREX Process, European Nuclear Society

- Mixed Oxide Fuel (MOX) - World Nuclear Association

- Disposal Options for Surplus Weapons-Usable Plutonium - Congressional Research Service Report for Congress

- Brief History of Fuel Reprocessing