P-adic quantum mechanics

This article provides an introduction to the subject, followed by a review of the mathematical concepts involved. It then considers modern research on the subject, from Schrödinger-like equations to more exploratory ideas. Finally it lists some precise examples that have been considered.

Introduction

Another motivation for applying p-adic analysis to science is that the divergences that plague quantum field theory remain problematic as well. It is felt that by exploring different approaches, such inelegant techniques as renormalization might become unnecessary.[4] Another consideration is that since no primes have any special status in p-adic analysis, it might be more natural and instructive to work with adeles.

There are two main approaches to the subject.[5][6] The first considers particles in a p-adic potential well, and the goal is to find solutions with smoothly varying complex-valued wavefunctions. Here the solutions to have a certain amount of familiarity from ordinary life. The second considers particles in p-adic potential wells, and the goal is to find p-adic valued wavefunctions. In this case, the physical interpretation is more difficult. Yet the math often exhibits striking characteristics, therefore people continue to explore it. The situation was summed up in 2005 by one scientist as follows: "I simply cannot think of all this as a sequence of amusing accidents and dismiss it as a 'toy model'. I think more work on this is both needed and worthwhile."[7]

Review of p-adic and adelic analysis

The ordinary real numbers are familiar to everyone. Still reasonably familiar, but less so, are the integers mod n. They are sometimes studied in courses on number theory. It turns out that they have major significance. Ostrowski's theorem states that there are essentially two kinds of completions of the rational numbers, depending on the metric considered: these are the real numbers and the p-adic numbers. One completes the rationals by adding the limit of all Cauchy sequences to the set. The completions are different because of the two different ways of measuring distance.[note 2] The former obey a triangle inequality of the form |x+y| ≤ |x| + |y|, but the latter obey the stronger form of |x+y| ≤ max{|x|, |y|}; this is sometimes called an ultrametric space.

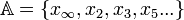

There is a question of how to unify these two foundational ideas, as they behave very differently in both space and time. This is solved by considering the patterns that occur, when one welds them together into a single mathematical object. This is the ring of adeles. It is of the form

where  is a real number, and the

is a real number, and the  are in

are in  . The infinity sign in

. The infinity sign in  stands for the "prime at infinity". It is required that all but finitely many of the

stands for the "prime at infinity". It is required that all but finitely many of the  lie in their corresponding

lie in their corresponding  . The adele ring is therefore a restricted direct product. The idele group is defined as the essentially invertible elements:

. The adele ring is therefore a restricted direct product. The idele group is defined as the essentially invertible elements:

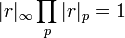

Many familiar structures carry over to the adeles. For example, trigonometric functions, ex and log (x) have been constructed, as well as special functions like the Riemann zeta function, along with integral transforms like the Mellin and Fourier transform.[8] This ring has many interesting properties. For instance, quadratic polynomials obey the Hasse local-global principle: a rational number is the solution of a quadratic polynomial equation if and only if it has a solution in R and Qp for all primes p. In addition, the real and p-adic norms are related to each other by the remarkable adelic product formula:[9]

where  is a nonzero rational number. For example, one might consider the number 12. In this case, r2 = 0011, r3 = 011, r5 = 22, r7 = 51 and r11 = 11. So |r|2 = 1/4, |r|3 = 1/3, |r|5 = 1, |r|7 = 1, |r|11 = 1, and all the rest are ones. Hence, 12*1/4*1/3*1*1*1*1*1*1*1 = 1. In string theory, a similar product formula holds not only at the tree level, but generalization to full amplitudes has also been proposed.[3] This is covered in more detail later in the article.

is a nonzero rational number. For example, one might consider the number 12. In this case, r2 = 0011, r3 = 011, r5 = 22, r7 = 51 and r11 = 11. So |r|2 = 1/4, |r|3 = 1/3, |r|5 = 1, |r|7 = 1, |r|11 = 1, and all the rest are ones. Hence, 12*1/4*1/3*1*1*1*1*1*1*1 = 1. In string theory, a similar product formula holds not only at the tree level, but generalization to full amplitudes has also been proposed.[3] This is covered in more detail later in the article.

The research

- Fractal potential wells

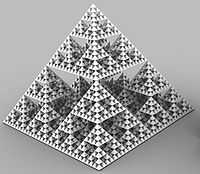

Many upper-division science students are familiar with the particle in a box, or the particle in a ring. But there are also other types of potential wells. For instance, one may also consider the fractal potential wells. The solution of Schrödinger-like equations for potentials of this kind has been of interest for some time. Not only is it challenging to solve for puzzles like this, but it can be used for approximating complicated potentials as well, such as those that arise in the design of microchips. For example, one group of authors study the Schrödinger equation as it applies to a self-similar potential.[10] Another group studied the potentials constructed from the Riemann zeros and prime number sequences. They estimate the fractal dimension to be D = 1.5 for the Riemann zeros, and D = 1.8 for the prime numbers.[11]

The question of what happens when waves interact with fractal structures has been studied by many researchers.[12][13] The p-adic numbers are an excellent method for constructing fractal potential wells. For instance, one might consider a Dirac potential. This is simply a flat plane that contains a negative-valued Dirac delta function. One can think of this as a positive integer surrounded by zeros, and each of those surrounded by zeros, and each of those surrounded by zeros, and so on. As another example, one may think of a number surrounded by half its value, and each of those numbers by half their value, and so on. In this case it is more interesting, because half of 3 mod 7 is 5; therefore it seems to be bigger.

- Path integrals

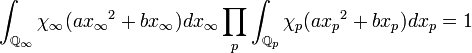

As early as 1965, Feynman had stated that path integrals have fractal-like properties.[14] And, as there does not exist a suitable p-adic Schrödinger equation,[15][16] path integrals are employed instead. One author states that "Feynman's adelic path integral is a fundamental object in mathematical physics of quantum phenomena".[17] In order to do computations, certain details have to be made precise. For instance, one may define a meaningful derivative operator. In addition, both A and A* have a translation-invariant Haar measure:[18]

This allows one to compute integrals. For the sum over histories, Gaussian integrals are vital. It turns out that Gaussian integrals satisfy a generalization of the adelic product formula introduced before, namely:[18]

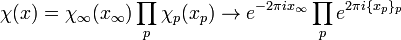

where  is an additive character from the adeles to C given by[18]

is an additive character from the adeles to C given by[18]

and  is the fractional part of

is the fractional part of  in the ordinary p-adic expression for x. This can be thought of as a strong generalization of the homomorphism

in the ordinary p-adic expression for x. This can be thought of as a strong generalization of the homomorphism

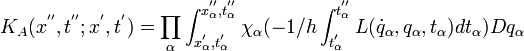

Now the adelic path integral, with input parameters in A and generating complex-valued wavefunctions is[19]

and similar to the case for real parameters, the eigenvalue problem is[19]

where  is the time-development operator,

is the time-development operator,  are adelic eigenfunctions, and

are adelic eigenfunctions, and  is the adelic energy. Here the notation has been simplified by using the subscript

is the adelic energy. Here the notation has been simplified by using the subscript  , which stands for all primes including the prime at infinity. One notices the additive character

, which stands for all primes including the prime at infinity. One notices the additive character  which allows these to be complex-valued integrals. The path integral can be generalized to p-adic time as well.[20]

which allows these to be complex-valued integrals. The path integral can be generalized to p-adic time as well.[20]

- Lorentz group

The p-adic generalization of the Lorentz group has been considered.[21] In 2008, an article was published on the group, in fields over primes congruent to 7 mod 8.[22] The author finds dense subsets of the group over the rationals, maps them to the group over the p-adic numbers, and finally to the group over the integers mod a prime. In this way, arbitrarily dense subsets of the group can be found.

- Finite fields

The research has not been limited to the inverse limit of the integers mod a prime number, because all finite fields have similar constructions. In fact, every finite field is the quotient of an ideal of that inverse limit, and therefore the system is actually a tower of ideals. The study of quantum mechanics in finite fields has been considered by a number of authors.[23][24] One motivation is that if spacetime is discrete, then perhaps continuous spacetime can be viewed as an approximation to finite fields. The theory of supersymmetry has been studied in finite fields as well.[25]

- Riemann zeta function

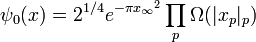

It can be shown that ground state of adelic quantum harmonic oscillator is[18][26]

where  is 1 if

is 1 if  is a p-adic integer, and 0 otherwise. One notices the close similarity to the ordinary complex-valued ground state. Applying the adelic version of the Mellin transform, we have

is a p-adic integer, and 0 otherwise. One notices the close similarity to the ordinary complex-valued ground state. Applying the adelic version of the Mellin transform, we have

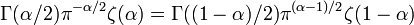

where  is the gamma function, and

is the gamma function, and  is the Riemann zeta function. Now there is a famous functional equation called the Tate formula, which says that

is the Riemann zeta function. Now there is a famous functional equation called the Tate formula, which says that

Here the left hand side is the Mellin transform, and the right hand side is the Mellin transform of the Fourier transform. But just as in the ordinary case, the Fourier transform does not change the result. So one can apply this formula to the previous one, and we arrive at the famous functional relation for the Riemann zeta function:

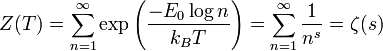

"It is remarkable that such simple physical system as harmonic oscillator is related to so significant mathematical object as the Reimann zeta function".[5] In addition, the statistical mechanics partition function for the free Riemann gas[note 3] is given by the Riemann zeta function:

- Veneziano amplitude

Another application involves the adelic product formula in a different way. In string theory, one computes crossing symmetric Veneziano amplitudes. The amplitude A (a, b) describes the scattering of four tachyons in the 26-dimensional open bosonic string. These amplitudes are not easy to compute. However, in 1987 an adelic product formula for this was discovered; it is[5]

This allows the four-point amplitudes, and all higher amplitudes to be computed at the tree level exactly, as the inverse of the much simpler p-adic amplitudes. This discovery has generated a quite a bit of activity in string theory.[27] The situation is not as easy for the closed bosonic string, but studies are still being pursued.

- Representation theory

P-adic representation theory has been extensively studied. One group of authors studies the structure of elementary particles, by means of the projective representations of the p-adic Poincaré group. This a generalization of the famous theorem of Wigner, who showed that all projective unitary representations of the Poincaré group lift to unitary representations of its (universal) double cover. They show that the p-adic version of massive particles cannot have conformal symmetry, by studying the embedding of the p-adic Poincaré group into the p-adic conformal spacetime.[4] Another group studied p-adic symplectic theory; more specifically, the representations of GL(2n) over a p-adic field that admit an invariant under the symplectic group.[28] Yet another has studied "extrametaplectic" representations.[29]

- Principal bundles

The math associated with this study is elegantly formulated in the language of gauge theory. In particular, one studies the wavefunctions in a tangent space known as a principal bundle. This helps to formulate a self-consistent theory. In this case, there is an idele-group bundle. It can be matrix-valued, in which case it may be noncommutative as well.

- Quantum cosmology

The theory has also been applied to quantum cosmology.[30] One group of authors study the relevance of "quantum rolling tachyons and corresponding inflation scenario" in terms of adelic quantum cosmology.[31]

Examples

This section presents concrete examples of fractal or adelic systems which have been studied.

One dimensional systems

The following one dimensional systems have been studied by means of the path integral formulation: the free particle,[2] the particle in a constant field,[32] the harmonic oscillator,[8] and others as well.

Particle on a Sierpinski gasket

Particle on a Cantor set

One group numerically solve a rescaled version of the Schrödinger equation for a particle in a Cantor-like potential.[35]

Notes

- ↑ There is no known analytical solution. Instead, numerical techniques are used to solve puzzles of this type.

- ↑ The two spaces are complete as a metric space, but neither are algebraically complete. That requires generalizing to an infinite-dimensional space.

- ↑ This is not a real gas, but rather a fictitious one. One might think of the famous experiment of heating up hydrogen gas, and viewing the spectral lines. In the same way, heating up the free Riemann gas would allow one to view (the differences of) a series based on the prime numbers.

References

- ↑ I.V.Volovich, Number theory as the ultimate theory, CERN preprint, CERN-TH.4791/87

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 V. S. Vladimirov, P-adic Analyisis and Mathematical Physics, (World Scientific, Singapore 1994)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 L. Brekke and P. G. O. Freund, P-adic numbers in physics, Phys. Rep. 233, 1-66(1993)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 http://www.arxiv.org:1002.0047, Structure, classification, and conformal symmetry of elementary particles over non-archimedean space-time, V. S. Varadarajan, Jukka T. Virtanen

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Branko Dragovich, Adeles in Mathematical Physics (2007), http://arxiv.org/abs/0707.3876

- ↑ page 3, second paragraph, Goran S. Djordjevic and Branko Dragovich, p-Adic and Adelic Harmonic Oscillator with Time-Dependent Frequency, http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0005027

- ↑ Peter G.O. Freund, p-adic Strings and their Applications, http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-th/0510192

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Branko Dragovich, Adelic Harmonic Oscillator, http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-th/0404160

- ↑ Branko Dragovich, Andrei Khrennikov and Dusan Mihajlovic, Linear Fractional p-Adic and Adelic Dynamical Systems, http://arxiv.org/abs/math-ph/0612058

- ↑ N L Chuprikov, O V Spiridonova, A new type of solutions of the Schrödinger equation on a self-similar fractal potential, http://www.arxiv:quant-ph/0607097

- ↑ Brandon P. van Zyl, D. A. W. Hutchinson, Riemann zeros, prime numbers and fractal potentials, http://arxiv.org/abs/nlin/0304038

- ↑ M. Berry, J. Phys. A 12, 781 (1979)

- ↑ F. Bihua and F. Duan, Chem. Phys. Lett. 5, 9(1988)

- ↑ R. P. Feynman and A. R. Hibbs, Quantum Mechanics and Path Integrals, (McGraw-Hill, 1965)

- ↑ Page two, last paragraph, arxiv:0804.1328, Quantum Cosmology and Tachyons, D. D. Dimitrijevic, G. S. Djordjevic, Lj. Nesic

- ↑ Also page two, last paragraph, arxiv:1011.6589, Path Integrals for Quadratic Lagrangians on p-Adic and Adelic Spaces, Branko Dragovich

- ↑ Branko Dragovich, Path Integrals for Quadratic Lagrangians on p-Adic and Adelic Spaces, http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.6589

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Branko Dragovich, On Generalized Functions in Adelic Quantum Mechanics, http://arxiv.org/abs/math-ph/0404076

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Branko Dragovich, p-Adic and Adelic Quantum Mechanics, http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-th/0312046

- ↑ Branko Dragovich, On p-adic path integral, http://arxiv.org/abs/math-ph/0005020

- ↑ E. G. Beltrametti, Note on the p-adic generalization of the lorentz transform, Discrete Mathematics, 1(1971), 139-146

- ↑ Stephan Fouldes, The Lorentz group and its finite field analogues: local isomorphism and approximation, http://arxiv.org/abs/0805.1224

- ↑ arxiv:hep-th/0605294, Quantum Theory and Galois Fields, Felix Lev

- ↑ arxiv:hep-th/0209001, Elementary Particles in a Quantum Theory Over a Galois Field, Felix Lev

- ↑ arxiv:hep-th/0209229, Supersymmetry in Quantum Theory Over a Galois Field, Felix Lev

- ↑ arxiv:hep-th/0402193, Adelic Model of Harmonic Oscillator, Branko Dragovich

- ↑ Debashis Ghoshal, Quantum Extended Arithmetic Veneziano Amplitude, http://arxiv.org/abs/math-ph/0606003

- ↑ arxiv:0806.4031, On Unitary Representations of GL2n Distinguished by the Symplectic Group, Omer Offen, Eitan Sayag

- ↑ arxiv:0903.1417, Multiplicity one theorems for Fourier-Jacobi models, Binyong Sun

- ↑ Branko Dragovich and Ljubisa Nesic, p-Adic and Adelic Generalization of Quantum Cosmology, http://arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/0005103

- ↑ G. S. Djordjevic and Lj. Nesic, Non-archimedean quantum cosmology and tachyonic inflation, http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.2885

- ↑ Branko Dragovich, On p-adic functional integration, Proc of the II mathematical conference, Yugoslavia, (1997) 221-228

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 http://arxiv.org/PS_cache/arxiv/pdf/1105/1105.1995v1.pdf, Differential 1-forms, their Integrals and Potential Theory on the Sierpinski Gasket, Fabio Cipriani, Daniele Guido, Tommaso Isola, Jean-Luc Sauvageot

- ↑ arxiv:0205105, Dimensional crossover and hidden incommensurability in Josephson junction arrays of periodically repeated Sierpinski gaskets, R.Meyer, S.E.Korshunov, Ch.Leemann, P.Martinoli

- ↑ D. Hadjimichef, Bound-State Problem in a One-Dimensional Cantor-like Potential, http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9806064