Amu Darya

| Amu Darya | |

| Oxus, Jayhoun, də Āmu Sind, Vaksu, Amu River | |

Looking at the Amu Darya from Turkmenistan | |

| Name origin: Named for city of Āmul (now Turkmenabat) | |

| Countries | Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan |

|---|---|

| Region | Central Asia |

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Panj River |

| - right | Vakhsh River, Surkhan Darya, Sherabad River, Zeravshan River |

| Primary source | Pamir River/Panj River |

| - location | Lake Zorkul, Pamir Mountains, Tajikistan |

| - elevation | 4,130 m (13,550 ft) |

| - coordinates | 37°27′04″N 73°34′21″E / 37.45111°N 73.57250°E |

| Secondary source | Kyzyl-Suu/Vakhsh River |

| - location | Alay Valley, Pamir Mountains, Kyrgyzstan |

| - elevation | 4,525 m (14,846 ft) |

| - coordinates | 39°13′27″N 72°55′26″E / 39.22417°N 72.92389°E |

| Source confluence | Kerki |

| - elevation | 326 m (1,070 ft) |

| - coordinates | 37°06′35″N 68°18′44″E / 37.10972°N 68.31222°E |

| Mouth | Aral Sea |

| - location | Amudarya Delta, Uzbekistan |

| - elevation | 28 m (92 ft) |

| - coordinates | 44°06′30″N 59°40′52″E / 44.10833°N 59.68111°E |

| Length | 2,400 km (1,491 mi) |

| Basin | 534,739 km2 (206,464 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| - average | 2,525 m3/s (89,170 cu ft/s) [1] |

Map of the Amu Darya watershed

| |

The Amu Darya (Persian: آمودریا, Āmūdaryā; Turkmen: Amyderýa; Uzbek: Amudaryo; Tajik: Амударё; Pashto: د آمو سيند, da Āmú Sínd; Ancient Greek: Ὦξος, Oxos; Latin: Oxus), also called Amu River, is a major river in Central Asia. It is formed by the junction of the Vakhsh and Panj rivers. In ancient times, the river was regarded as the boundary between Greater Iran and Turan.[2]

Names

In classical antiquity, the river was known as the Ōxus in Latin and Ὦξος Oxos in Greek — a clear derivative of Vakhsh — the name of the largest tributary of the river.[citation needed] In Vedic Sanskrit, the river is also referred to as Vaksu (वक्षु). The Avestan texts too refer to the River as Yaksha-arte.

In ancient Afghanistan, the river was also called Gozan, descriptions of which can be found in the book "The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch By George Passman Tate".[3][4] In Middle Persian sources of the Sassanid period the river is known as Wehrōd[2] (lit. "good river").

The name Amu is said to have come from the medieval city of Āmul, (later, Chahar Joy/Charjunow, and now known as Türkmenabat), in modern Turkmenistan, with Darya being the Persian word for "river".

Medieval Arabic and Muslim sources call the river Jayhoun (جيحون) which is derived from Gihon, the biblical name for one of the four rivers of the Garden of Eden.[5][6]

Amu Darya is a river almost in reverse, for long reputed to be sourced by a powerful glacier-fed stream high in the Pamir Knot at the eastern end of Afghanistan's Wakhan Corridor, and ending not at the sea but spreading out into the sands of Turkmenistan's Kyzyl Kum desert, well short of its historic terminus of the inland Aral Sea.

As the river Gozan

Historians mention that one of the names for the Oxus or Amu in ancient Afghanistan was Gozan, and that this name was used by Greek, Mongol, Chinese, Persian, Jewish, and Afghan historians. However, this name is no longer used.

- "Hara (Bokhara) and to the river of Gozan (that is to say, the Amu, (called by Europeans the Oxus)....".[7]

- "the Gozan River is the River Balkh, i.e. the Oxus or the Amu Darya.....".[8]

- "... and were brought into Halah (modern day Balkh), and Habor (which is Pesh Habor or Peshawar), and Hara (which is Herat), and to the river Gozan (which is the Ammoo, also called Jehoon)...".[9]

Description

The river's total length is 2,400 kilometres (1,500 mi) and its drainage basin totals 534,739 square kilometres (206,464 sq mi) in area, providing a mean discharge of around 97.4 cubic kilometres (23.4 cu mi)[1] of water per year. The river is navigable for over 1,450 kilometres (900 mi). All of the water comes from the high mountains in the south where annual precipitation can be over 1,000 mm (39 in). Even before large-scale irrigation began, high summer evaporation meant that not all of this discharge reached the Aral Sea - though there is some evidence the large Pamir glaciers provided enough melt water for the Aral to overflow during the 13th and 14th centuries.

Since the end of the 19th century there have been four different claimants as the true source of the Oxus: 1: the Pamir River, which emerges from Lake Zorkul (once also known as Lake Victoria) in the Pamir Mountains (ancient Mount Imeon), and flows west to Qila-e Panja, where it joins the Wakhan River to form the Panj River. 2: the Sarhad or Little Pamir River flowing down the Little Pamir in the High Wakhan 3: Lake Chamaktin, which discharges to the east into the Aksu River, which in turn becomes the Murghab and then Bartang rivers, and which eventually joins the Panj Oxus branch 350 kilometres downstream at Roshan Vomar in Tajikistan. 4: an ice cave at the end of the Wakhjir valley, in the Wakhan Corridor, in the Pamir Mountains, near the border with Pakistan.

A glacier turns into the Wakhan River and joins the Pamir River about 50 kilometres (31 mi) downstream.[10] Bill Colegrave's expedition to Wakhan in 2007 found that both claimants 2 and 3 had the same source, the Chelab stream, which bifurcates on the watershed of the Little Pamir, half flowing into Lake Chamaktin and half into the parent stream of the Little Pamir/Sarhad River. Therefore the Chelab stream may be properly considered the true source or parent stream of the Oxus.[11] The Panj River forms the border of Afghanistan and Tajikistan. It flows west to Ishkashim where it turns north and then north-west through the Pamirs passing the Tajikistan-Afghanistan Friendship Bridge. It subsequently forms the border of Afghanistan and Uzbekistan for about 200 kilometres (120 mi), passing Termez and the Afghanistan-Uzbekistan Friendship Bridge. It delineates the border of Afghanistan and Turkmenistan for another 100 kilometres (62 mi) before it flows into Turkmenistan at Atamurat. As the Amudarya, it flows across Turkmenistan south to north, passing Türkmenabat, and forms the border of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan from Halkabat. It is then split into many waterways that are used to form the river delta joining the Aral Sea, passing Urgench, Daşoguz, and other cities, but it does not reach what is left of the sea anymore and is lost in the desert.

Use of water from the Amu Darya for irrigation has been a major contributing factor to the shrinking of the Aral Sea since the late 1950s.

Historical records state that in different periods, the river flowed into the Aral Sea (from the south), into the Caspian Sea (from the east), or both, similar to the Syr Darya (Jaxartes, in Ancient Greek).

Watershed

About 1,385,045 square kilometres (534,769 sq mi) of land is drained by the Amu Darya into the Aral Sea endorheic basin. This includes most of Tajikistan, the southwest corner of Kyrgyzstan, the northeast corner of Afghanistan, a long narrow portion of eastern Turkmenistan and about half of Uzbekistan. Part of the Amu Darya's drainage divide in Tajikistan forms that country's border with China (in the east) and Pakistan (to the south). About 61% of the drainage lies within Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, while 39% is in Afghanistan.[12] Of the area drained by the Amu Darya, only about 200,000 square kilometres (77,000 sq mi) actively contribute water to the river.[13] This is because many of the river's major tributaries (especially the Zeravshan River) have been diverted, and much of the river's drainage is dominated by outlying desert and steppe.

The abundant water flowing in the Amu Darya comes almost entirely from glaciers in the Pamir Mountains and Tian Shan,[14] which, standing above the surrounding arid plain, collect atmospheric moisture which otherwise would probably escape somewhere else. Without its mountain water sources, the Amu Darya would not contain any water—would not exist—because it rarely rains in the lowlands through which most of the river flows. Throughout most of the steppe, the annual rainfall is about 300 millimetres (12 in).[12][15]

History

.jpg)

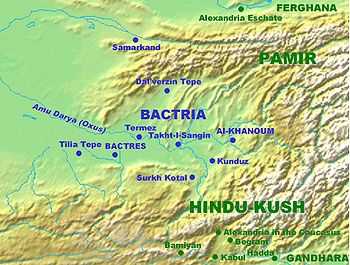

The Amu Darya was called the Oxus by the ancient Greeks. In ancient times, the river was regarded as the boundary between Greater Iran and Tūrān.[2] The river's drainage lies in the area between the former empires of Genghis Khan and Alexander the Great, although they occurred at much different times. When the Monguls lived in the area, they used the water of the Amu Darya to flood Konye-Urgench.[16] One southern route of the Silk Road ran along part of the Amu Darya northwestward from Termez before going westwards to the Caspian Sea.

It is believed that the Amu Darya's course across the Kara-Kum Desert has gone through several major shifts in the past few thousand years. Much of the time, the most recent period being in the 13th century to the late 16th century, the Amu Darya emptied into both the Aral and the Caspian Seas, the latter via a large distributary called the Uzboy River. The Uzboy splits off from the main channel just south of the Amudarya Delta. Sometimes, the flow through the two branches was more or less equal, but often, most of the Amu Darya's flow split to the west and flowed into the Caspian.

People began to settle along the lower Amu Darya and the Uzboy in the 5th century, establishing a thriving chain of agricultural lands, towns, and cities. The river was impounded in about 985 AD at the bifurcation of the forks by the massive Gurganj Dam, which diverted water to the Aral. The dam was destroyed by Genghis Khan's troops in 1221, and the Amu Darya shifted its flows more or less equally between the main stem and the Uzboy.[17] But in the 18th century, the river again turned north, flowing into the Aral Sea, a path it has taken since. Less and less water flowed down the Uzboy until, in the 1720s, the river's surface flow completely dried up.[18]

The first Englishman to reach the Oxus was William Moorcroft about 1824.[19] Another to reach the region in the Great Game period was a naval officer called John Wood. He was sent on an expedition to find the source of the river in 1839. He found modern day Lake Zorkul, called it Lake Victoria and proclaimed he had found the source.[20] Then, the French explorer and geographer Thibaut Viné collected a lot of informations about this area during five expeditions between 1856 and 1862.

The question of finding a route between the Oxus valley and India has been of concern historically. A direct route crosses extremely high mountain passes in the Hindu Kush and isolated areas like Kafiristan. It was feared by some in Britain that the Empire of Russia, which at the time held a large influence over the Oxus area, would overcome these obstacles and find a suitable route through which to invade British India but this never came to pass.[21]

The Soviet Union became the ruling power in the early 1920s and expelled Mohammed Alim Khan. It later put down the Basmachi movement and killed Ibrahim Bek. A large refugee population of Central Asians, including Turkmen, Tajiks and Uzbeks, fled to northern Afghanistan.[22] In the 1960s and 1970s, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya were first used by the Soviets to irrigate extensive cotton fields in the Central Asian plain. Before this time, water from the rivers was already being used for agriculture, but not on this massive scale. The Qaraqum Canal, Karshi Canal, and Bukhara Canal were among the larger of the irrigation diversions built. The 1970s Soviet war in Afghanistan used the valley to invade the country through Termez.[23] The Soviet Union fell in the 1990s and Central Asia split up into the many smaller countries that lie within or partially within the Amu Darya basin.[24] The Main Turkmen Canal was a proposed project that would have diverted water along the dry Uzboy River bed into central Turkmenistan, but was never built.

Literature

But the majestic River floated on,

Out of the mist and hum of that low land,

Into the frosty starlight, and there moved,

Rejoicing, through the hushed Chorasmian waste,

Under the solitary moon: — he flowed

Right for the polar star, past Orgunjè,

Brimming, and bright, and large: then sands begin

To hem his watery march, and dam his streams,

And split his currents; that for many a league

The shorn and parcelled Oxus strains along

Through beds of sand and matted rushy isles —

Oxus, forgetting the bright speed he had

In his high mountain-cradle in Pamere,

A foiled circuitous wanderer: — till at last

The longed-for dash of waves is heard, and wide

His luminous home of waters opens, bright

And tranquil, from whose floor the new-bathed stars

Emerge, and shine upon the Aral Sea.

~ Matthew Arnold, Sohrab and Rustum

The Oxus river, and Arnold's poem, provide a literary background for the 1930s children's book The Far-Distant Oxus.

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 http://www.ce.utexas.edu/prof/mckinney/papers/aral/CentralAsiaWater-McKinney.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 B. Spuler, ĀMŪ DARYĀ, in Encyclopædia Iranica, online ed., 2009

- ↑ http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tGTd9KKwKVwC&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=allintext:+%3D+gozan+oxus+amu&source=bl&ots=ZDHOgiLp1e&sig=Du0XLu3_E3vhhGiArc3JU_iqJHk&hl=en&ei=CBHhTPm6IYnsuAPGkKjYDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBYQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=allintext%3A%20%3D%20gozan%20oxus%20amu&f=false

- ↑ http://library.du.ac.in/dspace/bitstream/1/4715/4/Ch.1 The kingdom of Afghanistan (page 1-87).pdf

- ↑ William C. Brice. 1981. Historical Atlas of Islam (Hardcover). Leiden with support and patronage from Encyclopaedia of Islam. ISBN 90-04-06116-9.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Amu Darya

- ↑ The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, By George Passman Tate, Page 11.

- ↑ Jews in Islamic countries in the Middle Ages, By Moshe Gil, David Strassler, Page 428.

- ↑ Tamerlane and the Jews, By Michael Shterenshis, Page xxiv.

- ↑ Mock,J., O'Neil, K. (2004) Expedition Report

- ↑ Colegrave, Bill (2011). Halfway House to Heaven. London: Bene Factum Publishing. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-903071-28-1.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Rakhmatullaev, Shavkat; Huneau, Frédéric; Jusipbek, Kazbekov; Le Coustumer, Philippe; Jumanov, Jamoljon; El Oifi, Bouchra; Motelica-Heino, Mikael; Hrkal, Zbynek. "Groundwater resources use and management in the Amu Darya River Basin (Central Asia)". Environmental Earth Sciences. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ Agaltseva, N.A.; Borovikova, L.N.; Konovalov, V.G. (1997). "Automated system of runoff forecasting for the Amudarya River basin". Destructive Water: Water-Caused Natural Disasters, their Abatement and Control. International Association of Hydrological Sciences. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ "Basin Water Organization "Amudarya"". Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ↑ "Amudarya River Basin Morphology". Central Asia Water Information. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ Sykes, Percy (1921). A History of Persia. London: Macmillan and Company. p. 64.

- ↑ Volk, Sylvia (2000-11-11). "The Course of the Oxus River". University of Calgary. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ↑ Kozubov, Robert (November 2007). "Uzboy". Turkmenistan Analytic Magazine. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ↑ Peter Hopkirk,"The Great Game",1994, page 100

- ↑ Keay, J. (1983) When Men and Mountains Meet ISBN 0-7126-0196-1 Chapter 9

- ↑ See for example "Can Russia invade India?" by Henry Bathurst Hanna, 1895, (Google eBook), or "The Káfirs of the Hindu-Kush", Sir George Scott Robertson, Illustrated by Arthur David McCormick, Lawrence & Bullen, Limited, 1896, (Google eBook)

- ↑ Taliban and Talibanism in Historical Perspective, M Nazif Shahrani, chapter 4 of The Taliban And The Crisis of Afghanistan, 2008 Harvard Univ Press, ed by Robert D Crews and Amin Tarzi

- ↑ Termez - See the Soviet war in Afghanistan article

- ↑ Pavlovskaya, L.P. "Fishery in the Lower Amu Darya Under the Impact of Irrigated Agriculture". Karakalpak Branch. Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

References

- Curzon, George Nathaniel. 1896. The Pamirs and the Source of the Oxus. Royal Geographical Society, London. Reprint: Elibron Classics Series, Adamant Media Corporation. 2005. ISBN 1-4021-5983-8 (pbk; ISBN 1-4021-3090-2 (hbk).

- Gordon, T. E. 1876. The Roof of the World: Being the Narrative of a Journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. Reprint by Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company. Taipei. 1971.

- Toynbee, Arnold J. 1961. Between Oxus and Jumna. London. Oxford University Press.

- Wood, John, 1872. A Journey to the Source of the River Oxus. With an essay on the Geography of the Valley of the Oxus by Colonel Henry Yule. London: John Murray.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amu Darya. |

| |||||||||||