Oxia Palus quadrangle

| Oxia Palus quadrangle | |

|---|---|

Map of Oxia Palus quadrangle from Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) data. The highest elevations are red and the lowest are blue. | |

| Coordinates | 15°00′N 22°30′W / 15°N 22.5°WCoordinates: 15°00′N 22°30′W / 15°N 22.5°W |

The Oxia Palus quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Oxia Palus quadrangle is also referred to as MC-11 (Mars Chart-11).[1]

The quadrangle covers the region of 0° to 45° west longitude and 0° to 30° north latitude on Mars. Mars Pathfinder landed in the Oxia Palus quadrangle at 19°08′N 33°13′W / 19.13°N 33.22°W, on July 4, 1997. Crater names in Oxia Palus are a Who's Who for famous scientists. Besides Galilaei and DaVinci, some of the people who discovered the atom and radiation are honored there: Curie, Becquerel, and Rutherford.[2] Mawrth Vallis was strongly considered as a landing site for NASA's next Mars rover, the Mars Science Laboratory.[3] This quadrangle contains abundant evidence for past water in such forms as river valleys, lakes, springs, and chaos areas where water flowed out of the ground. A variety of clay minerals have been found in Oxia Palus. Clay is formed in water, and it is good for preserving microscopic evidence of ancient life.[4] Recently, scientists have found strong evidence for a lake located in the Oxia Palus quadrangle that received drainage from Shalbatana Vallis. The study, carried out with HiRISE images, indicates that water formed a 30-mile-long canyon that opened up into a valley, deposited sediment, and created a delta. This delta and others around the basin imply the existence of a large, long-lived lake. Of special interest is evidence that the lake formed after the warm, wet period was thought to have ended. So, lakes may have been around much longer than previously thought. [5][6]

Surface appearance

The Mars Pathfinder found its landing site to contain a great deal of rocks. Analysis shows the area to have a greater density of rocks than 90% of Mars. Some of the rocks leaned against each other in a manner geologists term imbricated. It is believed strong flood waters in the past pushed the rocks around to face away from the flow. Some pebbles were rounded, perhaps from being tumbled in a stream. Some rocks have holes on their surfaces that seem to have been fluted by wind action. Small sand dunes are present. Parts of the ground are crusty, maybe due to cementing by a fluid containing minerals. In general the rocks show a dark gray color with patches of red dust or weathered appearance on their surfaces. Dust covers the lower 5–7 cm of some rocks, so they may have once been buried, but have now become exhumed. Three knobs, one large crater, and two small craters were visible on the horizon.[7]

Types of rocks

Results of Mars Pathfinder's Alpha Proton X-ray Spectrometer indicated that some rocks in the Oxia Palus quadrangle are like Earth's andesites. The discovery of andesites shows that some Martian rocks have been remelted and reprocessed. On Earth, Andesite forms when magma sits in pockets of rock while some of the iron and magnesium settle out. Consequently, the final rock contains less iron and magnesium and more silica. Volcanic rocks are usually classified by comparing the relative amount of alkalis (Na2O and K2O) with the amount of silica (SiO2). Andesite is different than the rocks found in meteorites that have come from Mars.[7][8][9]

By the time that final results of the mission were described in a series of articles in the Journal Science (December 5, 1997), it was believed that the rock Yogi contained a coating of dust, but was similar to the rock Barnacle Bill. Calculations suggest that the two rocks contain mostly the minerals orthopyroxene (magnesium-iron silicate), feldspars (aluminum silicates of potassium, sodium, and calcium), quartz (silicon dioxide), with smaller amounts of magnetite, ilmenite, iron sulfide, and calcium phosphate.[7][8][9]

-

Map of Oxia Palus labeled with major features.

-

View from Mars Pathfinder.

Other results from Pathfinder

By taking multiple images of the sky at different distances form the sun, scientists were able to determine that size of the particles in the pink haze was about 1 micrometer in radius. The color of some soils was similar to that of an iron oxyhydroxide phase which would support a warmer and wetter climate in the past.[10] Pathfinder carried a series of magnets to examine the magnetic component of the dust. Eventually, all but one of the magnets developed a coating of dust. Since the weakest magnet did not attract any soil, it was concluded that the airborne dust did not contain pure magnetite or one type of maghemite. The dust probably was an aggregate possible cemented with ferric oxide (Fe2O3).[11]

Winds were usually less than 10 m/s. Dust devils were detected in the early afternoon. The sky had a pink color. There was evidence of clouds and maybe fog.[7]

River valleys and chaos

Many large, ancient river valleys are found in this area; along with collapsed features, called Chaos. The Chaotic features may have collapsed when water came out of the surface. Martian rivers begin with a Chaos region. A chaotic region can be recognized by a rat's nest of mesas, buttes, and hills, chopped through with valleys which in places look almost patterned. Some parts of this chaotic area have not collapsed completely—they are still formed into large mesas, so they may still contain water ice.[12] Chaotic terrain occurs in numerous locations on Mars, and always gives the strong impression that something abruptly disturbed the ground. More information and more examples of chaos can be found at Chaos terrain. Chaos regions formed long ago. By counting craters (more craters in any given area means an older surface) and by studying the valleys' relations with other geological features, scientists have concluded the channels formed 2.0 to 3.8 billion years ago.[13]

One generally accepted view for the formation of large outflow channels is that they were formed by catastrophic floods of water released from giant groundwater reservoirs. Perhaps, the water started to come out of the ground due to faulting or volcanic activity. Sometimes hot magma just travels under the surface. If that is the case, the ground will be heated, but there may be no evidence of lava at the surface. After water escapes, the surface collapses. Moving across the surface, the water would have simultaneously froze and evaporated. Chunks of ice that would have rapidly formed may have enhanced the erosive power of the flood. Furthermore, the water may have frozen over at the surface, but continuing to flow underneath, eroding the ground as it moved along. Rivers in cold climates on the Earth often become ice-covered, yet continue to flow.

Such catastrophic floods have occurred on Earth. One commonly cited example is the Channeled Scabland of Washington State; it was formed by the breakout of water from the Pleistocene Lake Missoula. This region resembles the Martian outflow channels.[14]

Lakes

Research, published in January 2010, suggests that Mars had lakes, each around 20 km wide, along parts of the equator, in the Oxia Palus quadrangle. Although earlier research showed that Mars had a warm and wet early history that has long since dried up, these lakes existed in the Hesperian Epoch, a much earlier period. Using detailed images from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the researchers speculate that there may have been increased volcanic activity, meteorite impacts, or shifts in Mars' orbit during this period to warm Mars' atmosphere enough to melt the abundant ice present in the ground. Volcanoes would have released gases that thickened the atmosphere for a temporary period, trapping more sunlight and making it warm enough for liquid water to exist. In this new study, channels were discovered that connected lake basins near Ares Vallis. When one lake filled up, its waters overflowed the banks and carved the channels to a lower area where another lake formed.[15][16] These lakes would be another place to look for evidence of present or past life.

Aram Chaos

Aram Chaos is an ancient impact crater near the Martian equator, close to Ares Vallis. About 280 kilometers (170 mi) across, Aram lies in a region called Margaritifer Terra, where many water-carved channels show that floods poured out of the highlands onto the northern lowlands ages ago. The Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) on the Mars Odyssey orbiter found gray crystalline hematite on the floor of Aram. Hematite is an iron-oxide mineral that can precipitate when ground water circulates through iron-rich rocks, whether at normal temperatures or in hot springs. The floor of Aram contains huge blocks of collapsed, or chaotic, terrain that formed when water or ice was catastrophically removed. Elsewhere on Mars, the release of groundwater produced massive floods that eroded the large channels seen in Ares Vallis and similar outflow valleys. In Aram Chaos, however, the released water stayed mostly within the crater's ramparts, eroding only a small, shallow outlet channel in the eastern wall. Several minerals including hematite, sulfate minerals, and water-altered silicates in Aram suggests that a lake probably once existed within the crater. Because forming hematite requires liquid water, which could not long exist without a thick atmosphere, Mars must have had a much thicker atmosphere at some time in the past, when the hematite was formed.[17]

-

Erosion in Aram Chaos, as seen by THEMIS.

-

Blocks in Aram showing possible source of water, as seen by THEMIS.

Layered sediments

Oxia Palus is an interesting area with many craters showing layered sediments.[18] Such sediments may have been deposited by water, wind, or volcanoes. The thickness of the layers is different in different craters. In Becquerel many layers are about 4 meters thick. In Crommelin crater the layers average 20 meters in thickness. At times, the top layer may be resistant to erosion and will form a feature called a Mensa, the Latin word for table.[19]

The pattern of layers within layers measured in Becquerel crater, suggests that each layer was formed over a period of about 100,000 years. Moreover, every 10 layers can be grouped into larger bundles. So every 10-layer pattern took one-million years to form (100,000 yrs./layer X 10 layers). The 10-layer pattern is repeated at least 10 times that is there are least 10 bundles, each consisting of 10 layers. It is believed that the layers relate to the cycle of changing tilt of Mars.

The tilt of the Earth's axis changes by only a little more than 2 degrees. In contrast Mars's tilt varies by tens of degrees. Today, the tilt (or obliquity) of Mars is low, so the poles are the coldest places on the planet, while the equator is the warmest. This causes gases in the atmosphere, like water and carbon dioxide, to migrate poleward, where they turn into ice. When the obliquity is higher, the poles receive more sunlight, and those materials migrate away. When carbon dioxide moves from the poles, the atmospheric pressure increases, maybe causing a difference in the ability of winds to transport and deposit sand. With more water in the atmosphere, sand grains deposited on the surface may stick and cement together to form layers.

This study was done using stereo topographic maps obtained by processing data from the high-resolution camera onboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.[20]

-

Buttes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Buttes have layered rocks with a hard resistant cap rock on the top which protects the underlying rocks from erosion.

-

Possible dikes and layered structures, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

-

Possible fault along a butte, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

-

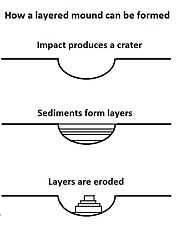

Mounds in craters showing layers are formed by the erosion of layers that were deposited after the impact.

-

Crommlin Crater Layered Deposit, as seen by HiRISE. The color blue in the photo is a false color.

-

Fault across layers in a mesa, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

-

Close-up of layers in Oxia Palus, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

-

Wide view of layered surface in Oxia Palus, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

-

Punsk Crater, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 500 meters long. Click on image to see possible fine layers on floor. Image on right is an enlargement of south (bottom) wall of crater.

-

Hydraotes Chaos, as seen by HiRISE. Click on image to seen channels and layers. Scale bar is 1000 meters long.

-

Grindavik Crater, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 1000 meters long.

-

Layers in Monument Valley. These are accepted as being formed, at least in part, by water deposition. Since Mars contains similar layers, water remains as a major cause of layering on Mars.

-

Layered mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Location in Terra Meridiani.

-

Close-up of one of mesas in previous photo showing layers. Mesa may be the remains of a lake in which sediments were deposited. Picture obtained with HiRISE, under HiWish program.

-

Wide-view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Box shows location of next image. Dark parts of image are dark, basalt sand sitting on level places.

-

Enlargement of previous image showing a fault and layers. Image taken with HiRISE, under HiWish program.

Wrinkle ridges

Many areas of Mars show wrinkles on the surface, called wrinkle ridges. They are elongated and are often found on smooth area of Mars. Because they are wide, gentle topographic highs, they are sometimes hard to see. Although first thought to be caused by lava flows, they are now generally thought to be more likely caused by compressional tectonic forces that cause folding and faulting. A wrinkle ridge is visible in the image to the right of Ares Vallis.[21]

Faults

A picture below right, taken of layers in Becquerel Crater, shows a straight line that represents a fault.[22] Faults are breaks in rocks where movement has taken place. The movement may be only inches or much more. Faults can be very significant, as the break in the rock is a focus for erosion and, more importantly, can allow fluids containing dissolved minerals to rise, then be deposited. Some of the major ore deposits on Earth are formed by this process.

Springs

A study of images taken with the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter strongly suggests that hot springs once existed in Vernal Crater, in the Oxia Palus quadrangle. These springs may have provided a long-time location for life. Furthermore, mineral deposits associated with these springs may have preserved traces of Martian life. In Vernal Crater on a dark part of the floor, two light-toned, elliptical structures closely resemble hot springs on the Earth. They have inner and outer halos, with roughly circular depressions. A large number of hills are lined up close to the springs. These are thought to have formed by the movement of fluids along the boundaries of dipping beds. A picture below shows these springs. One of the depressions is visible. The discovery of opaline silica by the Mars Rovers, on the surface also suggests the presence of hot springs. Opaline silica is often deposited in hot springs.[23] Scientists proposed this area should be visited by the Mars Science Laboratory.[24]

-

Springs in Vernal Crater, as seen by HIRISE

Mojave Crater

Mojave Crater, in the Xanthe Terra region, has alluvial fans that look remarkably similar to landforms in the Mojave Desert in the American southwest. Fans inside and around the outside of Mojave crater on Mars are a perfect match to Earth's alluvial fans. As on Earth, the largest rocks are near the mouths of the fans. Because channels start at the top of ridges, it is believed they were formed by heavy downpours. Researchers have suggested that rain may have initiated by impacts.[25]

Mojave Crater is approximately 2,604 meters (1.63 miles) deep. Based on its diameter and depth, researchers believe it is very young. It has not been around long enough to accumulate material and start to fill. It is giving scientists great insight into impact processes on Mars since it is so fresh.[26]

-

Alluvial Fans in Mojave Crater, as seen by HiRISE. High ground is on the right. Branched network of channels runs from higher ground (crater rim) to lower ground.

-

Another view of Mojave Crater, as seen by HiRISE. North is at the bottom to aid in understanding image.

Other craters

Impact craters generally have rims with ejecta around them; in contrast volcanic craters usually do not have a rim or ejecta deposits. As craters get larger (greater than 10 km in diameter) they usually have a central peak.[27] The peak is caused by a rebound of the crater floor following the impact.[21] Sometimes craters display layers. Since the collision that produces a crater is like a powerful explosion, rocks from deep underground are tossed onto the surface. Hence, craters can show what lies deep under the surface.

-

Trouvelot Crater floor, as seen by HiRISE

-

Central peak of Radau Crater, as seen by HiRISE

-

Kipini Crater south rim, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Sagan Crater Central Peak Ring, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Curie Crater, as seen by HiRISE

-

Close-up of layers in central mound of Curie Crater, as seen by HiRISE

-

Tayray Crater, as seen by HiRISE

-

Light toned rocks surrounded by dark material along wall of a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Click on image for a better view.

-

Pedestal Crater and ridge in Oxia Palus quadrangle, as seen by HiRISE. Click on image to see detail of the edge of the pedestal crater. The flat-topped ridge near the top of the image was once a river that became inverted. The pedestal crater superposes the ridge, so it is younger.

-

Pedestal craters form when the ejecta from impacts protect the underlying material from erosion. As a result of this process, craters appear perched above their surroundings.

-

Drawing shows a later idea of how some pedestal craters form. In this way of thinking, an impacting projectile goes into an ice-rich layer--but no further. Heat and wind from the impact hardens the surface against erosion. This hardening can be accomplished by the melting of ice which produces a salt/mineral solution thereby cementing the surface.

Vallis

Vallis (plural valles) is the Latin word for valley. It is used in planetary geology for the naming of landform features on other planets.

Vallis was used for old river valleys that were discovered on Mars, when probes were first sent to Mars. The Viking Orbiters caused a revolution in our ideas about water on Mars; huge river valleys were found in many areas. Spacecraft cameras showed that floods of water broke through dams, carved deep valleys, eroded grooves into bedrock, and traveled thousands of kilometers.[21][28][29]

-

Shalbatana Vallis, as seen by HiRISE. The scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Shalbatana Vallis Floor, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 1000 meters long.

-

Close-up of Simud Valles, as seen by HiRISE.

-

Ares Vallis, as seen by Viking. The channel is 25 km wide and about 1 km deep.

-

Channels in Ares Vallis Region, as seen by HiRISE.

-

Ares Valles, as seen by HiRISE

-

Tiu Valles Ridges, as seen by HiRISE. Ridges were probably formed by running water. Scale bar is 1 km long.

-

Teardrop-shaped islands caused by flood waters from Maja Valles, as seen by Viking Orbiter. Image is located in Oxia Palus quadrangle. The islands are formed in the ejecta of Lod Crater, Bok Crater, and Gold Crater.

Other close-ups in Oxia Palus quadrangle

-

Eos Chasma with a Mensa, a flat topped prominence with cliff-like edges, as seen by THEMIS. In many places rock layers are visible.

-

Hydaspis Chaos, as seen by HiRISE.

-

Cyclic Bedding in Arabia Terra, as seen by HiRISE.

-

Cliffs and canyons in Arabia, as seen by HiRISE.

See also

- Chaos terrain

- Climate of Mars

- Geology of Mars

- Groundwater on Mars

- Impact crater

- List of quadrangles on Mars

- List of rocks on Mars

- McLaughlin crater

- Pedestal crater

- Vallis

- Water on Mars

References

- ↑ Davies, M.E.; Batson, R.M.; Wu, S.S.C. “Geodesy and Cartography” in Kieffer, H.H.; Jakosky, B.M.; Snyder, C.W.; Matthews, M.S., Eds. Mars. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 1992.

- ↑ U.S. department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, Topographic Map of the Easern Region of Mars M 15M 0/270 2AT, 1991

- ↑ http://www.space.com/missionlaunches/mars-science-laboratory-curiosity-landing-sites-100615.htm

- ↑ http://themis.asu.edu/features/marwrthvillis

- ↑ http://www.colorado.edu/news/r/7e9c22ec0cd6dabc007bb14ed2e29f16.html

- ↑ http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/090617-Mars-lake.html

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Golombek, M. et al. 1997. Overview of the Mars Pathfinder Mission and Assessment of Landing Site Predictions. Science: 278. pp. 1743–1748

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 APXS Composition Results (NASA NSSDC)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bruckner, J., G. Dreibus, R. Rieder, and H. Wanke. 2001. Revised Data of the Mars Pathfinder Alpha Proton X-ray spectrometer: Geochemical Behavior of Major and Minor Elements. Lunar and Planetary Science XXXII

- ↑ Smith, P. et al. 1997. Results from the Mars Pathfinder Camera Science: 278. 1758-1765

- ↑ Hviid, S. et al. 1997. Magnetic Properties Experiments on the Mars Pathfinder Lander: Preliminary Results. Science:278. 1768-1770.

- ↑ http://themis.asu.edu/features/aramchaos

- ↑ http://themis.asu.edu/features/hydraotes

- ↑ http://www.msss.com/http/ps/channels/channels.html

- ↑ "Spectacular Mars Images Reveal Evidence of Ancient Lakes". Science Daily.

- ↑ Sanjeev Gupta, Nicholas Warner, Jung-Rack Kim, Shih-Yuan Lin, Jan Muller. 2010. Hesperian equatorial thermokarst lakes in Ares Vallis as evidence for transient warm conditions on Mars. Geology: 38. 71-74.

- ↑ http://themis.asu.edu/discoveries-aramchaos

- ↑ Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.) 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM

- ↑ http://themis.asu.edu/zoom-20050314a.html

- ↑ http://www.spaceref.com:80/news/viewpr.html.pid=27101

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Hugh H. Kieffer (1992). Mars. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1257-7. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_004078_2015

- ↑ Allen, C. and D. Oehler. 2008. A Case for Ancient Springs in Arabia Terra, Mars. Astrobiology. 8:1093-1112.

- ↑ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSO_002812_1855

- ↑ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_001415_1875

- ↑ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/dtm/dtm.php?ID=PSP_00481_1875

- ↑ http://www.lpi.usra.edu/publications/slidesets/stones/

- ↑ Raeburn, P. 1998. Uncovering the Secrets of the Red Planet Mars. National Geographic Society. Washington D.C.

- ↑ Moore, P. et al. 1990. The Atlas of the Solar System. Mitchell Beazley Publishers NY, NY.

External links

| Quadrangles on Mars | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC-01 Mare Boreum (features) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| MC-05 Ismenius Lacus (features) |

MC-06 Casius (features) |

MC-07 Cebrenia (features) |

MC-02 Diacria (features) |

MC-03 Arcadia (features) |

MC-04 Acidalium (features) | ||||||||||||||||||

| MC-12 Arabia (features) |

MC-13 Syrtis Major (features) |

MC-14 Amenthes (features) |

MC-15 Elysium (features) |

MC-08 Amazonis (features) |

MC-09 Tharsis (features) |

MC-10 Lunae Palus (features) |

MC-11 Oxia Palus (features) | ||||||||||||||||

| MC-20 Sinus Sabaeus (features) |

MC-21 Iapygia (features) |

MC-22 Mare Tyrrhenum (features) |

MC-23 Aeolis (features) |

MC-16 Memnonia (features) |

MC-17 Phoenicis Lacus (features) |

MC-18 Coprates (features) |

MC-19 Margaritifer Sinus (features) | ||||||||||||||||

| MC-27 Noachis (features) |

MC-28 Hellas (features) |

MC-29 Eridania (features) |

MC-24 Phaethontis (features) |

MC-25 Thaumasia (features) |

MC-26 Argyre (features) | ||||||||||||||||||

| MC-30 Mare Australe (features) | |||||||||||||||||||||||