Overtown (Miami)

| Overtown | |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood of Miami | |

| |

| Nickname(s): Colored Town (historic name) | |

| |

| Coordinates: 25°47′14.92″N 80°12′2.32″W / 25.7874778°N 80.2006444°WCoordinates: 25°47′14.92″N 80°12′2.32″W / 25.7874778°N 80.2006444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Miami-Dade County |

| City | Miami |

| Government | |

| • City of Miami Commissioner | Richard Dunn |

| • Miami-Dade Commissioners | Audrey Edmonson |

| • House of Representatives | Cynthia Stafford (D) |

| • State Senate | Larcenia Bullard (D) |

| • U.S. House | Frederica Wilson (D) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 6,736 |

| • Density | 8,820/sq mi (3,410/km2) |

| • Demonym | Towner |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-05) |

| ZIP Code | 33136 |

| Area code(s) | 305, 786 |

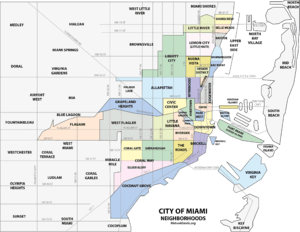

Overtown is a neighborhood of Miami, Florida, United States, just northwest of Downtown Miami. Originally called Colored Town during the Jim Crow era of the late 19th through the mid-20th century, the area was once the preeminent and is the historic center for commerce in the Black American community in Miami and South Florida.

Now roughly bound by North 20th Street to the north, North Fifth Street to the south, the Miami River and Dolphin Expressway (SR 836) to the west, and the Florida East Coast Railway (FEC) and West First Avenue to the east. Local residents often go by the demonym "Towners."

History

A part of the historic heart of Miami, it was designated as a "colored" neighborhood after the creation and incorporation of Miami in 1896. The incorporation of Miami as a city occurred at the insistence of Standard Oil and FEC railroad tycoon Henry Flagler, whose mostly black American railroad construction workers settled near what became Downtown Miami, just north of Flagler's Royal Palm Hotel on the Miami River. Owing to a substantive African American population, 168 of the 362 men who voted for the creation of the city of Miami were counted as "colored," but the separate but equal segregation laws of the Deep South dictated the city designate the portion of the city, in this case, north and west of FEC railroad tracks, as "Colored Town."[1]

The second-oldest continuously inhabited neighborhood of the Miami area after Coconut Grove, the area thrived as a center for commerce, primarily along Northwest Second Avenue. Home to the Lyric Theatre (completed in 1913) and other businesses, West Second Avenue served as the main street of the black community during an era which, up until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, barred African American residents from entering middle and upper income white areas like Miami Beach and Coral Gables without "passes."[2] During the Florida land boom of the 1920s, Overtown was home to one of the first black millionaires in the American South, D. A. Dorsey (who once owned Fisher Island), and the original Booker T. Washington High School, then the first high school educating black students south of Palm Beach.[2] Community organizing and mobilization during the era, as such in actions of Reverend John Culmer, who advocated for better living conditions for lower class blacks living in abject squalor during the 1920s, led to the completion of Liberty Square in 1937 in what is now-called Liberty City. Northwest Second Avenue and the surrounding neighborhood, once-called the "Little Broadway" of the South,[3] by the 1940s hosted hundreds of mostly black-owned businesses, ranging from libraries and social organizations to a hospital and popular nightclubs.

Popular with blacks and whites alike,[4] Overtown was a center for nightly entertainment in Miami, comparable to Miami Beach, at its height post-World War II in the 1940s and 1950s. The area served as a place of rest and refuge for black mainstream entertainers such as Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Cab Calloway, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, and Nat King Cole who were not allowed to lodge at prominent venues where they performed like the Fontainebleau and the Eden Roc, where Overtown hotels like the Mary Elizabeth Hotel furnished to their needs. Further, many prominent African American luminaries like W. E. B. Du Bois, Zora Neale Hurston, Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson lodged and entertained in the neighborhood.[5]

The area experienced serious economic decline from the late 1950s. Issues ranging from urban renewal to the construction of interstate highways like I-95 (then, the North-South Expressway), the Dolphin Expressway and the Midtown Interchange in the 1960s, fragmented the-once thriving center with the resident population decimated by nearly 80 percent from roughly 50,000 to just over 10,000.[6] The area became economically destitute and considered a "ghetto" as businesses closed and productivity stagnated in the neighborhood.[7]

Development was spurred in the area again in the late 1980s with the construction and completion of the Miami Arena and transit-oriented development surrounding the newly opened Overtown station. Since the 1990s and 2000s (decade), community gardens have been created, in addition to renovations to the historic Lyric Theatre and revitalization and gentrification efforts spurred both by the city of Miami and Miami-Dade County.

Demographics

As of 2000,[8] Overtown had a population of 10,029 residents, with 3,646 households, and 2,128 families residing in the city. The median household income was $13,211.99. The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 19.90% Hispanic or Latino of any race, 74.77% Black or African American, 3.27% White (non-Hispanic), and 2.05% Other races (non-Hispanic).

Places of interest

Overtown is home to several historic churches and landmarks listed in the National Register of Historic Places, including:

- Dana Albert Dorsey House (250 NW 9th Street): built in 1913, was home to Dana Albert Dorsey, one of Miami's most prominent black businessmen and philanthropists;[9]

- Greater Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (245 NW 8th Street): built from 1927 to 1943, was the home of one of Miami's oldest African-American congregations;[10]

- Lyric Theater (819 NW 2nd Ave): built in 1914, was a focal point of social life of the African-American community;[11]

- Mt. Zion Baptist Church (301 NW 9th Street): built from 1928 to 1941, was the church of one of Miami's oldest congregations;[12]

- St. John's Baptist Church (1328 NW 3rd Avenue): built in 1940, is an example of Art Deco style religious buildings in Miami-Dade County.[13]

Other places of interest included in the City of Miami Historic Preservation Program are:

- Dorsey Memorial Library (100 NW 17th Street): built in 1941, was the first city-owned building constructed specifically as a library;[14]

- Dr. William A. Chapman House (526 NW 13th Street): built in 1923, was home of Miami's first black physicians;[15]

- Ebenezer Methodist Church (1042 NW 3rd Avenue): built in 1948, is an example of Gothic Revival design;[16]

- Hindu Temple (870 NW 11th Street): built in 1920 inspired to the sets of the film The Jungle Trial, was home to the merchant John Seybold;[17]

- St. Agnes' Episcopal Church (1750 NW 3rd Avenue): built from 1923 to 1930 to house one of Miami's oldest African-American congregations;[18]

- Ward Rooming House (249 NW 9th Street): built in 1925, is a gallery and visitor center;[19]

- X-Ray Clinic (171 NW 11th Street): built in 1939 as office for South Florida's first African-American radiologist Dr. Samuel H. Johnson.[20]

Parks and recreation

- Ninth Street Pedestrian Mall, NW 9th Street - NW 2nd Avenue;

- Dorsey Park, 1701 NW 1st Ave;[21]

- Gibson Park, 401 NW 12th St;[22]

- Henry Reeves Park, 600 NW 10th St;[23]

- Spring Garden Point Park, 601 NW 7th Street Rd;

- Town Park, NW 17th Street - NW 5th Avenue;

- Williams Park, 1717 NW 5th Ave.;[24]

Education and institutions

Schools

Miami-Dade County Public Schools:

- Frederick Douglass Elementary School, 314 NW 12th St;[25]

- Paul Laurence Dunbar K-8, 505 NW 20th St;[26]

- Phillis Wheatley Elementary School, 1801 NW 1st Pl;[27]

- Booker T. Washington Senior High School, 1200 NW 6th Ave;[28]

- Theodore R. and Thelma A. Gibson Charter School, 1682 NW 4th Ave.[29]

Libraries

- Overtown Public Library (350 NW 13th St),[30] with its exterior walls adorned with paintings by Overtown's famous urban expressionist painter, Purvis Young.

Museums

- Black Police Precinct & Courthouse Museum, 480 NW 11th St.[31]

Places of worship

In addition to the churches listed in the places of interest section, in the neighborhood there are:[32]

- A.M. Cohen Temple Church of God in Christ, 1747 NW 3rd Ave

- Christ Church of The Living God, 225 NW 14th Ter

- Greater Israel Bethel Primitive Baptist Church, 160 NW 18th St

- Greater Mercy Missionary Baptist Church, 1135 NW 3rd Ave

- Mt. Olivette Baptist Church, 1450 NW 1st Ct

- New Hope Primitive Baptist Church, 1301 NW 1st Pl

- Saint Peter’s Antiochian Orthodox Catholic Church, 1811 NW 4th Ct

- St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church, 1682 NW 4th Ave

- Temple Baptist Church, 1723 NW 3rd Ave

- Triumph The Church and Kingdom of God in Christ, 1752 NW 1st Ct

Other institutions

- Miami-Dade County - Culmer Neighborhood Service Center, 1600 NW 3rd Ave;[33]

- City of Miami - Overtown Neighborhood Enhancement Team, 1490 NW 3rd Ave Suite 112-B;[34]

- Southeast Overtown/Park West Community Redevelopment Agency, 1490 NW 3rd Ave Ste 105;[35]

- Overtown Youth Center, 450 NW 14th St NW 3rd Ave.[36]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Overtown is served by the Miami Metrorail at:

- Historic Overtown/Lyric Theatre (NW Eighth Street and First Avenue)

- Culmer (NW 11th Street and US 441)

Health care

- Jefferson Reaves Sr. Health Center, 1009 NW 5th Ave NW 10th Street.[37]

Gallery

-

D.A. Dorsey House, built in 1914

-

Lyric Theater, 1914

-

St. John's Baptist Church, 1940

-

Mt. Zion Baptist Church, 1928

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Overtown (Miami). |

- "Overtown: Inside/Out" Multimedia project c. 2009-2011 - Video from Overtown with commentary from Towners

References

- ↑ Mjagkij, Nina (2001). Organizing Black America: An Encyclopedia of African American Associations. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-8153-2309-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mjagkij 2001

- ↑ Savage, Beth (1995). African American Historic Places. Washington, D.C.: National Register for Historic Places. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-471-14345-1.

- ↑ Bird, Christiane (2001). The Da Capo Jazz and Blues Lover's Guide to the United States. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-306-81034-3.

- ↑ Jones, Maxine; Kevin McCarthy (1993). African Americans in Florida. Key West, Florida: Pineapple Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-56164-031-7.

- ↑ Hirsch, Arnold; Raymond A. Mohl (1993). Urban Policy in Twentieth-Century America. Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8135-1906-7.

- ↑ Simms, Bob (21 July 1975). "Minority Experience: Welcome to the Ghetto, It's No Place Like Home". The Miami News. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ "Demographics of Overtown Miami, FL". miamigov.com. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "D. A. Dorsey House". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "Greater Bethel AME Church". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "Lyric Theater". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "Mt. Zion Baptist Church". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "St. John's Baptist Church". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "Dorsey Memorial Library". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "D.A. Dorsey House". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "Ebenezer Methodist Church". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "Hindu Temple". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "St. Agnes' Episcopal Church". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "Ward Rooming House". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ Historic preservation program. "X-Ray Clinic". City of Miami Planning Department. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Dorsey Park". City of Miami Parks and Recreation. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Gibson Park". City of Miami Parks and Recreation. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Henry Reeves Park". City of Miami Parks and Recreation. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Williams Park". City of Miami Parks and Recreation. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Frederick Douglass Elementary School". Miami-Dade County Public Schools. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Paul Laurence Dunbar K-8". Miami-Dade County Public Schools. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Phillis Wheatley Elementary". Miami-Dade County Public Schools. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Booker T. Washington Senior High School". Miami-Dade County Public Schools. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Theodore & Thelma Gibson Charter School". Theodore & Thelma Gibson Charter School. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Culmer/Overtown Branch". Miami-Dade Public Library System. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Black Police Precinct Courthouse and Museum". Black Police Precinct Courthouse and Museum. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Faith Based Organizations". City of Miami Neighborhood Enhancement Team. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Culmer Center". Miami-Dade County Community Action and Human Services. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Overtown NET". City of Miami Neighborhood Enhancement Team. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Southeast Overtown/Park West Community Redevelopment Agency". Miami Community Redevelopment Agency. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Overtown Youth Center". Overtown Youth Center. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Jefferson Reaves, Sr. Health Center". Jackson Health System. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

| |||||||