Ovary

| Ovary | |

|---|---|

| |

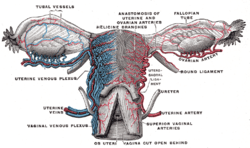

| Blood supply of the human female reproductive organs. The left ovary is visible above the label "ovarian arteries". | |

| Latin | ovarium |

| Gray's | subject #266 1254 |

| Artery | ovarian artery, uterine artery |

| Vein | ovarian vein |

| Nerve | ovarian plexus |

| Lymph | Paraaortic lymph node |

| MeSH | Ovary |

| Dorlands/Elsevier | Ovary |

The ovary (From Latin: ovarium, literally “egg” or “nut”) is an ovum-producing reproductive organ, often found in pairs as part of the vertebrate female reproductive system. Ovaries in female individuals are analogous to testes in male individuals, in that they are both gonads and endocrine glands.

Structure

Each ovary is dark-black in color and located alongside the lateral wall of the Uterus in a region called the ovarian fossa. The fossa usually lies beneath the external iliac artery and in front of the ureter and the internal iliac artery. It is about 4 cm x 3 cm x 2 cm in size.[1]

Usually each ovary takes turns releasing an egg every month; however, if there was a case where one ovary was absent or dysfunctional then the other ovary would continue providing eggs to be released.

Ligaments

In the human the paired ovaries lie within the pelvic cavity, on either side of the uterus, to which they are attached via a fibrous cord called the ovarian ligament. The ovaries are uncovered in the peritoneal cavity but are tethered to the body wall via the suspensory ligament of the ovary. The part of the broad ligament of the uterus that covers the ovary is known as the mesovarium. Thus, the ovary is the only organ in the human body which is totally invaginated into the peritonium, making it the only intraperitoneal organ (not to be confused with interperitoneal).

Extremities

There are two extremities to the ovary:

- The end to which the fallopian tube attaches is called the tubal extremity and ovary is connected to it by infundibulopelvic ligament.[1]

- The other extremity is called the uterine extremity. It points downward, and it is attached to the uterus via the ovarian ligament.

Histology

- Follicular cells flat epithelial cells that originate from surface epithelium covering the ovary

- Granulosa cells - surrounding follicular cells have changed from flat to cuboidal and proliferated to produce a stratified epithelium

- Gametes[2]

- The outermost layer is called the ovarian surface epithelium (previously known as the germinal epithelium).

- The ovarian cortex consists of ovarian follicles and stroma in between them. Included in the follicles are the cumulus oophorus, membrana granulosa (and the granulosa cells inside it), corona radiata, zona pellucida, and primary oocyte. The zona pellucida, theca of follicle, antrum and liquor folliculi are also contained in the follicle. Also in the cortex is the corpus luteum derived from the follicles.

- The innermost layer is the ovarian medulla. It can be hard to distinguish between the cortex and medulla, but follicles are usually not found in the medulla.

The ovary also contains blood vessels and lymphatics.[3]

Function

Hormones

Ovaries secrete estrogen, testosterone[4][5][6][7] and progesterone. In women, fifty per cent of testosterone is produced by the ovaries and adrenal glands and released directly into the blood stream.[8] Estrogen is responsible for the appearance of secondary sex characteristics for females at puberty and for the maturation and maintenance of the reproductive organs in their mature functional state. Progesterone prepares the uterus for pregnancy, and the mammary glands for lactation. Progesterone functions with estrogen by promoting menstrual cycle changes in the endometrium.

Ovarian aging

As women age, they experience a decline in reproductive performance leading to menopause. This decline is tied to a decline in the number of ovarian follicles. Although about 1 million oocytes are present at birth in the human ovary, only about 500 (about 0.05%) of these ovulate, and the rest are wasted. The decline in ovarian reserve appears to occur at a constantly increasing rate with age,[9] and leads to nearly complete exhaustion of the reserve by about age 52. As ovarian reserve and fertility decline with age, there is also a parallel increase in pregnancy failure and meiotic errors resulting in chromosomally abnormal conceptions.

Women with an inherited mutation in the DNA repair gene BRCA1 undergo menopause prematurely,[10] suggesting that naturally occurring DNA damages in oocytes are repaired less efficiently in these women, and this inefficiency leads to early reproductive failure. The BRCA1 protein plays a key role in a type of DNA repair termed homologous recombinational repair that is the only known cellular process that can accurately repair DNA double-strand breaks. Titus et al.[11] showed that DNA double-strand breaks accumulate with age in humans and mice in primordial follicles. Primodial follicles contain oocytes that are at an intermediate (prophase I) stage of meiosis. Meiosis is the general process in eukaryotic organisms by which germ cells are formed, and it is likely an adaptation for removing DNA damages, especially double-strand breaks, from germ line DNA.[12] (see Meiosis and Origin and function of meiosis). Homologous recombinational repair is especially promoted during meiosis. Titus et al.[11] also found that expression of 4 key genes necessary for homologous recombinational repair of DNA double-strand breaks (BRCA1, MRE11, RAD51 and ATM) decline with age in the oocytes of humans and mice. They hypothesized that DNA double-strand break repair is vital for the maintenance of oocyte reserve and that a decline in efficiency of repair with age plays a key role in ovarian aging.

Society and culture

Cryopreservation

Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue, often called Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation, is of interest to women who want to preserve their reproductive function beyond the natural limit, or whose reproductive potential is threatened by cancer therapy,[13] for example in hematologic malignancies or breast cancer.[14] The procedure is to take a part of the ovary and carry out slow freezing before storing it in liquid nitrogen whilst therapy is undertaken. Tissue can then be thawed and implanted near the fallopian, either orthotopic (on the natural location) or heterotopic (on the abdominal wall),[14] where it starts to produce new eggs, allowing normal conception to take place.[15] A study of 60 procedures concluded that ovarian tissue harvesting appears to be safe.[14] The ovarian tissue may also be transplanted into mice that are immunocompromised (SCID mice) to avoid graft rejection, and tissue can be harvested later when mature follicles have developed.[16]

Disease

Ovarian diseases can be classified as endocrine disorders or as a disorders of the reproductive system.

If the egg fails to release from the follicle in the ovary an ovarian cyst may form. Small ovarian cysts are common in healthy women. Some women have more follicles than usual (polycystic ovary syndrome), which inhibits the follicles to grow normally and this will cause cycle irregularities.

In other animals

Ovaries of some kind are found in the female reproductive system of many animals that employ sexual reproduction, including invertebrates. However, they develop in a very different way in most invertebrates than they do in vertebrates, and are not truly homologous.[17]

Many of the features found in human ovaries are common to all vertebrates, including the presence of follicular cells, tunica albuginea, and so on. However, many species produce a far greater number of eggs during their lifetime than do humans, so that, in fish and amphibians, there may be hundreds, or even millions of fertile eggs present in the ovary at any given time. In these species, fresh eggs may be developing from the germinal epithelium throughout life. Corpora lutea are found only in mammals, and in some elasmobranch fish; in other species, the remnants of the follicle are quickly resorbed by the ovary. In birds, reptiles, and monotremes, the egg is relatively large, filling the follicle, and distorting the shape of the ovary at maturity.[17]

Amphibians and reptiles have no ovarian medulla; the central part of the ovary is a hollow, lymph-filled space. The ovary of teleosts is also often hollow, but in this case, the eggs are shed into the cavity, which opens into the oviduct.[17]

Although most normal female vertebrates have two ovaries, this is not the case in all species. In most birds and in platypuses, the right ovary never matures, so that only the left is functional. (Exceptions include the Kiwi and some, but not all raptors, in which both ovaries persist.[18][19]) In some elasmobranchs, only the right ovary develops fully. In the primitive jawless fish, and some teleosts, there is only one ovary, formed by the fusion of the paired organs in the embryo.[17]

Other conditions include

Additional Images

-

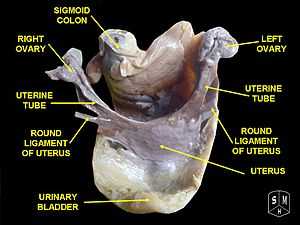

Left Ovary

-

Ovaries

-

Uterus

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ovary. |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Daftary, Shirish; Chakravarti, Sudip (2011). Manual of Obstetrics, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 1-16. ISBN 9788131225561.

- ↑ Langman's Medical Embryology, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 10th ed, 2006

- ↑ Brown, H. M.; Russell, D. L. (2013). "Blood and lymphatic vasculature in the ovary: Development, function and disease". Human Reproduction Update 20: 29. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt049.

- ↑ Normal Testosterone and Estrogen Levels in Women

- ↑ Testosterone - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- ↑ Testosterone: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

- ↑ Testosterone in Women

- ↑ Androgens in women

- ↑ Hansen KR, Knowlton NS, Thyer AC, Charleston JS, Soules MR, Klein NA. (2008). A new model of reproductive aging: the decline in ovarian non-growing follicle number from birth to menopause. Hum Reprod 23(3):699-708. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem408. PMID:18192670

- ↑ Rzepka-Górska I, Tarnowski B, Chudecka-Głaz A, Górski B, Zielińska D, Tołoczko-Grabarek A. (2006). Premature menopause in patients with BRCA1 gene mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat 100(1):59-63. PMID: 16773440

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Titus S, Li F, Stobezki R, Akula K, Unsal E, Jeong K, Dickler M, Robson M, Moy F, Goswami S, Oktay K. (2013). Impairment of BRCA1-related DNA double-strand break repair leads to ovarian aging in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med 5(172):172ra21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004925. PMID: 23408054

- ↑ Harris Bernstein, Carol Bernstein and Richard E. Michod (2011). Meiosis as an Evolutionary Adaptation for DNA Repair. Chapter 19 in DNA Repair. Inna Kruman editor. InTech Open Publisher. DOI: 10.5772/25117 http://www.intechopen.com/books/dna-repair/meiosis-as-an-evolutionary-adaptation-for-dna-repair

- ↑ Isachenko V, Lapidus I, Isachenko E, et al. (2009). "Human ovarian tissue vitrification versus conventional freezing: morphological, endocrinological, and molecular biological evaluation.". Reproduction 138 (2): 319–27. doi:10.1530/REP-09-0039. PMID 19439559.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Oktay K, Oktem O (November 2008). "Ovarian cryopreservation and transplantation for fertility preservation for medical indications: report of an ongoing experience". Fertil. Steril. 93 (3): 762–8. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.006. PMID 19013568.

- ↑ Livebirth after orthotopic transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue The Lancet, Sep 24, 2004

- ↑ Lan C, Xiao W, Xiao-Hui D, Chun-Yan H, Hong-Ling Y (December 2008). "Tissue culture before transplantation of frozen-thawed human fetal ovarian tissue into immunodeficient mice". Fertil. Steril. 93 (3): 913–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.020. PMID 19108826.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 383–385. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, F. L. 1934. Unilateral and bilateral ovaries in raptorial birds. The Wilson Bulletin 46 (1): 19-22.

- ↑ Kinsky, F. C. 1971. The consistent presence of paired ovaries in the Kiwi(Apteryx) with some discussion of this condition in other birds. Journal of Ornithology 112 (3): 334–357.

External links

| Look up ovary in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||