Orthogonal trajectory

In mathematics, orthogonal trajectories are a family of curves in the plane that intersect a given family of curves at right angles. The problem is classical, but is now understood by means of complex analysis; see for example harmonic conjugate.

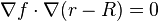

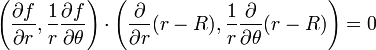

For a family of level curves described by  , where

, where  is a constant, the orthogonal trajectories may be found as the level curves of a new function

is a constant, the orthogonal trajectories may be found as the level curves of a new function  by solving the partial differential equation

by solving the partial differential equation

for  . This is literally a statement that the gradients of the functions (which are perpendicular to the curves) are orthogonal. Note that if

. This is literally a statement that the gradients of the functions (which are perpendicular to the curves) are orthogonal. Note that if  and

and  are functions of three variables instead of two, the equation above will be nonlinear and will specify orthogonal surfaces.

are functions of three variables instead of two, the equation above will be nonlinear and will specify orthogonal surfaces.

The partial differential equation may be avoided by instead equating the tangent of a parametric curve  with the gradient of

with the gradient of  :

:

which will result in two possibly coupled ordinary differential equations, whose solutions are the orthogonal trajectories. Note that with this formula, if  is a function of three variables its level sets are surfaces, and the family of curves

is a function of three variables its level sets are surfaces, and the family of curves  are orthogonal to the surfaces.

are orthogonal to the surfaces.

Example: circle

In polar coordinates, the family of circles centered about the origin is the level curves of

where  is the radius of the circle. Then the orthogonal trajectories are the level curves of

is the radius of the circle. Then the orthogonal trajectories are the level curves of  defined by:

defined by:

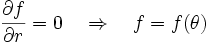

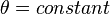

The lack of complete boundary data prevents determining  . However, we want our orthogonal trajectories to span every point on every circle, which means that

. However, we want our orthogonal trajectories to span every point on every circle, which means that  must have a range which at least include one period of rotation. Thus, the level curves of

must have a range which at least include one period of rotation. Thus, the level curves of  , with freedom to choose any

, with freedom to choose any  , are all of the

, are all of the  curves that intersect circles, which are (all of the) straight lines passing through the origin. Note that the dot product takes nearly the familiar form since polar coordinates are orthogonal.

curves that intersect circles, which are (all of the) straight lines passing through the origin. Note that the dot product takes nearly the familiar form since polar coordinates are orthogonal.

The absence of boundary data is a good thing, as it makes solving the PDE simple as one doesn't need to contort the solution to any boundary. In general, though, it must be ensured that all of the trajectories are found.

External links

- Exploring orthogonal trajectories - applet allowing user to draw families of curves and their orthogonal trajectories.