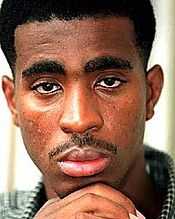

Orlando Anderson

| Orlando Anderson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Orlando Tive Anderson August 13, 1974 United States |

| Died |

May 29, 1998 (aged 23) United States |

| Occupation | Crips gang member |

Criminal charge | Murder suspect |

Orlando Tive "Baby Lane" Anderson (August 13, 1974 – May 29, 1998) was an alleged affiliate of the South Side Crips and a person of interest in the investigation into the murder of American rapper Tupac Shakur by Compton and the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Departments.[1] Specifically Detective Tim Brennan of Compton filed an affidavit naming Anderson as a suspect, although fans and others have speculated as to Anderson's involvement since the killing.[2] He was never charged with the murder.

Murder of Tupac Shakur

In 2002, The Los Angeles Times published a two-part series by reporter Chuck Philips, titled "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?," based on a yearlong investigation that reconstructed the crime and the events leading up to it. Information gathered by Phillips indicated that: "the shooting was carried out by a Compton gang called the Southside Crips to avenge the beating of one of its members by Shakur a few hours earlier. Orlando Anderson, the Crip whom Shakur had attacked, fired the fatal shots. Las Vegas police discounted Anderson as a suspect and interviewed him only once. He was later killed in an unrelated gang shooting." Philips's articles also included a reference to the cooperation of East Coast rappers including the late rapper The Notorious B.I.G., Tupac's rival at the time, and several New York criminals.[3][4]

Before they died, the late rapper The Notorious B.I.G. (who was killed on March 9, 1997) and Anderson denied their role in the murder. In support of their claims, Biggie's family produced computerized invoices showing that Biggie was working in a New York recording studio the night of the drive-by shooting. His manager Wayne Barrow and fellow rapper James "Lil' Cease" Lloyd made public announcements denying Biggie's role in the crime and stating further that they were both with him in the recording studio on the night of the event.[5] The New York Times called the evidence produced by Biggie's family "inconclusive" noting:

The pages purport to be three computer printouts from Daddy's House, indicating that Wallace was in the studio recording a song called Nasty Boy on the afternoon Shakur was shot. They indicate that Wallace wrote half the session, was In and out/sat around and laid down a ref, shorthand for a reference vocal, the equivalent of a first take.But nothing indicates when the documents were created. And Louis Alfred, the recording engineer listed on the sheets, said in an interview that he remembered recording the song with Wallace in a late-night session, not during the day. He could not recall the date of the session but said it was likely not the night Shakur was shot. We would have heard about it, Mr. Alfred said."[6]

Philips' articles, moreover, were based on police affidavits and court documents as well as interviews with investigators, witnesses to the crime and members of the Southside Crips who had never before discussed the killing outside the gang. As Assistant Managing Editor of the LA Times Mark Duvoisin wrote: "Philips' story has withstood all challenges to its accuracy, ...[and] remains the definitive account of the Shakur slaying."[7] The main thrust of Philips' investigation, implicating Anderson and the Crips, was later corroborated by former LAPD Detective Greg Kading's 2011 book Murder Rap'.'[8][9]

On the other hand, in her 2002 book The Killing of Tupac Shakur Cathy Scott [10] reviews various theories including the Suge Knight/Death row theory of Pac's murder before finally stating "Years after the primary investigations, it's still anyone's guess. No one was ever arrested but no one was ever ruled out as a suspect, either." She then concluded one theory "transcends all the others, and implicates the white-record-company power brokers themselves," implicating the bosses of the Suge Knight label. In recent years, her archived letters of her own responses to readers shows an evolution toward the Anderson theory and a dismissal of Knight as suspect. Archived Letters

Tupac Shakur's death and aftermath

On the night of September 7, 1996, Anderson, Shakur and Shakur's entourage were involved in a fight inside the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas one hour before Shakur's shooting. In October, Las Vegas homicide Lt. Larry Spinosa told the media, "At this point, Orlando Anderson is not a suspect in the shooting of Tupac Shakur."[11][12] Eventually in the investigation, Anderson was named a suspect.[13] Stories circulated on the street that Anderson bragged about shooting the rapper, which he denied in an interview for VIBE magazine later.[14] Anderson was detained in Compton a month after the shooting with 21 other alleged gang members. Anderson was not charged.[15] However, the raid was only tangentially connected to the Tupac shooting as Compton police said they were investigating local shootings and not the one in Las Vegas.[16] The Las Vegas police discounted Anderson as a suspect, because, according to a report by Chuck Philips, they had 1. discounted the fight that occurred just hours before the shooting, in which Shakur was involved in beating Orlando Anderson in the Las Vegas MGM lobby, 2. they failed to follow up with a member of Shakur's entourage who witnessed the shooting who told Vegas police he could probably identify one or more of the assailants—the witness was killed just weeks later, and 3. they failed to follow-up a lead from a witness who spotted a white Cadillac similar to the car from which the fatal shots were fired and from which the shooters escaped.[17]

A year later, Afeni Shakur, Tupac's mother, filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Anderson[18] in response to a lawsuit Anderson filed against Death Row Records CEO Suge Knight, Death Row associates, and Tupac's estate. Anderson's lawsuit sought damages for injuries resulting from the scuffle that evening, claiming to have suffered emotional and physical pain. Afeni Shakur's lawsuit was filed just four days after Anderson's.[19] The Associated Press reported in 2000 that Shakur's estate and Anderson's estate settled the competing lawsuits just hours before the death of Orlando Anderson.[20] Only Anderson's lawyer disclosed a dollar figure attached to the settlement which he claimed would have netted Anderson $78,000.[citation needed]

Anderson professed to being a fan and an admirer of Tupac Shakur and his music and said he was cleared by Las Vegas police after two days of questioning.[21]

Former LAPD Detective Greg Kading in October 2011, a former investigator in the murder of Christopher "Biggie Smalls" Wallace, released a book alleging that Sean “Diddy” Combs commissioned Duane Keith “Keffe D” Davis to kill Tupac Shakur, along with Knight, for $1 million. Davis, the uncle of Orlando Anderson, and Kading claimed that Anderson was present in the vehicle which pulled up next to the BMW in which Tupac was shot.[8][22] Kading's 2011 implication of Anderson was consistent with Philips two-part 2002 investigative piece.[3][4]

Death

On May 29, 1998, Orlando Anderson[23] and associates Michael Stone and Jerry Stone were involved in a shootout outside of Cigs Record Store in Compton, California.[24] They later died at Martin Luther King Jr.-Harbor Hospital (formerly King/Drew Medical Center) in Los Angeles, California.

References

- ↑ Brown, Jake (2002). "Guilty til proven innocent". Suge Knight: The Rise, Fall, and Rise of Death Row Records: The Story of Marion 'Suge' Knight, a Hard Hitting Study of One Man, One Company That Changed the Course of American Music Forever. Phoenix: Colossus Books. p. 32. ISBN 0-9702224-7-5.

- ↑ Associateds.info

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Philips, Chuck (September 6, 2002). "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Philips, Chuck (September 7, 2002). "How Vegas police probe floundered in Tupac Shakur case". LA Times. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Notorious B.I.G.'s Family 'Outraged' By Tupac Article". Streetgangs.com. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ Leland, John (October 7, 2002). "New Theories Stir Speculation On Rap Deaths". New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ Duvoisin, Mark (January 12, 2006). "L.A. Times Responds to Biggie Story". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Murder of Tupac

- ↑ Kading, Greg (2011). Murder Rap. US: One time publishing LLC. ISBN 978-0-9839554-8-1.

- ↑ Scott, Cathy (2002). The Killing of Tupac Shakur. US: Huntington Press LLC. ISBN 978-0929712208.

- ↑ NY Daily News: HE FOUGHT TUPAC ON FATAL NITE

- ↑ Transcript: Orlando Anderson's Interview with Sanyika Shakur for VIBE Magazine

- ↑ Brown, P.32

- ↑ - Transcript: Orlando Anderson's Interview with Sanyika Shakur for VIBE Magazine

- ↑ Las Vegas Sun, "22-year-old detained in Tupac Shakur killing," October 2, 1996

- ↑ Arrest made in connection to Shakur killing

- ↑ Philips, Chuck (September 7, 2002). "How Vegas police probe floundered in Tupac Shakur case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ↑ Philips, Chuck (September 13, 1997). "Shakur's Mother Files Wrongful-Death Suit". LA Times. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ↑ Afeni Shakur Files Lawsuit Four Days After Orland Anderson Files a Lawsuit Naming Tupac Shakur and Others As Defendents

- ↑ Associated Press Report: Estate of Tupac Shakur settles with another slain man's family

- ↑ Shakur Was His Hero, Not His Victim, Says Man Some Suspect

- ↑ Hip Hop DX interview with Detective Greg Kading

- ↑ Tupac Murder Suspect Orlando Anderson Dead MTV News Jun 1 1998

- ↑ Life and death in South Central LA News The Observer, Saturday 8 January 2000

External links

- Scott, Cathy, The Killing of Tupac Shakur, Huntington Press: ISBN 978-0-929712-20-8 (paperback 2nd ed., 2002)

- Philips, Chuck, "Who Killed Tupac Shakur; Part 1

- Philips, Chuck, "Who Killed Tupac Shakur; Part 2"