Oriented matroid

An oriented matroid is a mathematical structure that abstracts the properties of directed graphs and of arrangements of vectors in a vector space over an ordered field (particularly for partially ordered vector spaces).[1] In comparison, an ordinary (i.e., non-oriented) matroid abstracts the dependence properties that are common both to graphs, which are not necessarily directed, and to arrangements of vectors over fields, which are not necessarily ordered.[2] [3]

All oriented matroids have an underlying matroid. Thus, results on ordinary matroids can be applied to oriented matroids. However, the converse is false; some matroids cannot become an oriented matroid by orienting an underlying structure (e.g., circuits or independent sets).[4] The distinction between matroids and oriented matroids is discussed further below.

Matroids are often useful in areas such as dimension theory and algorithms. Because of an oriented matroid's inclusion of additional details about the oriented nature of a structure, its usefulness extends further into several areas including geometry and optimization.

Background

In order to abstract the concept of orientation on the edges of a graph to sets, one needs the ability to assign "direction" to the elements of a set. The way this achieved is with the following definition of signed sets.

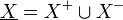

- A signed set,

, combines a set of objects

, combines a set of objects  with a partition of that set into two subsets:

with a partition of that set into two subsets:  and

and  .

.

- The members of

are called the positive elements; members of

are called the positive elements; members of  are the negative elements.

are the negative elements.

- The set

is called the support of

is called the support of  .

.

- The empty signed set,

is defined in the obvious way.

is defined in the obvious way.

- The signed set

is the opposite of

is the opposite of  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  , if and only if

, if and only if  and

and

Given an element of the support  , we will write

, we will write  for a positive element and

for a positive element and  for a negative element. In this way, a signed set is just adding negative signs to distinguish elements. This will make sense as a "direction" only when we consider orientations of larger structures. Then the sign of each element will encode its direction relative to this orientation.

for a negative element. In this way, a signed set is just adding negative signs to distinguish elements. This will make sense as a "direction" only when we consider orientations of larger structures. Then the sign of each element will encode its direction relative to this orientation.

Axiomatizations

Like ordinary matroids, several equivalent systems of axioms exist. (Such structures that possess multiple equivalent axiomatizations are called cryptomorphic.)

Circuit axioms

Let  be any set. We refer to

be any set. We refer to  as the ground set.

Let

as the ground set.

Let  be a collection of signed sets, each of which is supported by a subset of

be a collection of signed sets, each of which is supported by a subset of  .

If the following axioms hold for

.

If the following axioms hold for  , then equivalently

, then equivalently  is the set of signed circuits

for an oriented matroid on

is the set of signed circuits

for an oriented matroid on  .

.

- (C0)

- (C1) (symmetric)

- (C2) (incomparable)

- (C3) (weak elimination)

-

Chirotope axioms

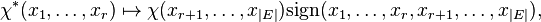

Let  be as above. A chirotope of rank

be as above. A chirotope of rank  is a function

is a function  that satisfies the following axioms.

that satisfies the following axioms.

- (B0)

is not identically zero

is not identically zero

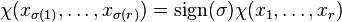

- (B1) (alternating) For any permutation

and

and  ,

,  , where

, where  is the sign of the permutation.

is the sign of the permutation.

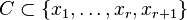

- (B2) (exchange) For any

such that

such that  for each

for each  , then we also have

, then we also have  .

.

The term chirotope is derived from the mathematical notion of chirality, which is a concept abstracted from chemistry used to distinguish molecules.

Equivalence

Every chirotope of rank  gives rise to a set of bases of a matroid on

gives rise to a set of bases of a matroid on  consisting of those

consisting of those  -element subsets that

-element subsets that  assigns a nonzero value.[5] The chirotope can then sign the circuits of that matroid. If

assigns a nonzero value.[5] The chirotope can then sign the circuits of that matroid. If  is a circuit of the described matroid, then

is a circuit of the described matroid, then  where

where  is a basis. Then

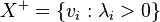

is a basis. Then  can be signed with positive elements

can be signed with positive elements

and negative elements the compliment. Thus a chirotope gives rise to the oriented bases of an oriented matroid. In this sense, (B0) is the nonempty axiom for bases and (B2) is the basis exchange property.

Examples

Oriented matroids are often introduced (e.g., Bachem and Kern) as an abstraction for directed graphs or systems of linear inequalities. Below are the explicit constructions.

Directed graphs

Given a digraph, we define a signed circuit from the standard circuit of the graph by the following method. The support of the signed circuit  is the standard set of edges in a minimal cycle. We go along the cycle in the clockwise or anticlockwise direction assigning those edges whose orientation agrees with the direction to the positive elements

is the standard set of edges in a minimal cycle. We go along the cycle in the clockwise or anticlockwise direction assigning those edges whose orientation agrees with the direction to the positive elements  and those edges whose orientation disagrees with the direction to the negative elements

and those edges whose orientation disagrees with the direction to the negative elements  . If

. If  is the set of all such

is the set of all such  , then

, then  is the set of signed circuits of an oriented matroid on the set of edges of the directed graph.

is the set of signed circuits of an oriented matroid on the set of edges of the directed graph.

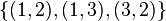

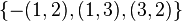

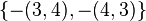

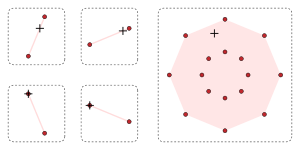

If we consider the directed graph on the right, then we can see that there are only two circuits, namely  and

and  . Then there are only four possible signed circuits corresponding to clockwise and anticlockwise orientations, namely

. Then there are only four possible signed circuits corresponding to clockwise and anticlockwise orientations, namely  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . These four sets form the set of signed circuits of an oriented matroid on the set

. These four sets form the set of signed circuits of an oriented matroid on the set  .

.

Linear algebra

If  is any finite subset of

is any finite subset of  , then the set of minimal linearly dependent sets forms the circuit set of a matroid on

, then the set of minimal linearly dependent sets forms the circuit set of a matroid on  . To extend this construction to oriented matroids, for each circuit

. To extend this construction to oriented matroids, for each circuit  there is a minimal linear dependence

there is a minimal linear dependence

with  . Then the signed circuit

. Then the signed circuit  has positive elements

has positive elements  and negative elements

and negative elements  . The set of all such

. The set of all such  forms the set of signed circuits of an oriented matroid on

forms the set of signed circuits of an oriented matroid on  . Oriented matroids that can be realized this way are called representable.

. Oriented matroids that can be realized this way are called representable.

Given the same set of vectors  , we can define the same oriented matroid with a chirotope

, we can define the same oriented matroid with a chirotope  . For any

. For any  let

let

where the right hand side of the equation is the sign of the determinant. Then  is the chirotope of the same oriented matroid on the set

is the chirotope of the same oriented matroid on the set  .

.

Convex polytope

Ziegler introduces oriented matroids via convex polytopes.

Results

Orientability

A standard matroid is called orientable if its circuits are the supports of signed circuits of some oriented matroid. It is known that all real representable matroids are orientable. It is also known that the class of orientable matroids is closed under taking minors, however the list of forbidden minors for orientable matroids is known to be infinite.[6] In this sense, oriented matroids is a much stricter formalization than regular matroids.

Duality

Much like matroids have unique dual, oriented matroids have unique orthogonal dual. What this means is the underlying matroids are dual and that the cocircuits are signed so that they are orthogonal to every circuit. Two signed sets are said to be orthogonal if the intersection of their supports is empty or if the restriction of their positive elements to the intersection and negative elements to the intersection form two nonidentical and non-opposite signed sets. The existence and uniqueness of the dual oriented matroid depends on the fact that every signed circuit is orthogonal to every signed cocircuit.[7] To see why orthogonality is necessary for uniqueness one needs only to look to the digraph example above. We know that for planar graphs, that the dual of the circuit matroid is the circuit matroid of the graph's planar dual. Thus there are as many different oriented matroids that are dual as there are ways to orient a graph and its dual.

To see the explicit construction of this unique orthogonal dual oriented matroid, consider an oriented matroid's chirotope  . If we consider a list of elements of

. If we consider a list of elements of  as a cyclic permutation then we define

as a cyclic permutation then we define  to be the sign of the associated permutation. If

to be the sign of the associated permutation. If  is defined as

is defined as

then  is the chirotope of the unique orthogonal dual oriented matroid.[8]

is the chirotope of the unique orthogonal dual oriented matroid.[8]

Topological representation

Oriented matroids are abstractions of geometric constructs. The exact constructs are arrangements of pseudospheres. A  -dimensional pseudosphere is an embedding of

-dimensional pseudosphere is an embedding of  such that there exists a homeomorphism

such that there exists a homeomorphism  so that

so that  embeds

embeds  as an equator of

as an equator of  . In this sense a pseudosphere is just a tame sphere (as opposed to wild spheres). A pseudosphere arrangement in

. In this sense a pseudosphere is just a tame sphere (as opposed to wild spheres). A pseudosphere arrangement in  is a collection of pseudospheres that intersect along pseudospheres. The Folkman Lawrence topological representation theorem states that every oriented matroid of rank

is a collection of pseudospheres that intersect along pseudospheres. The Folkman Lawrence topological representation theorem states that every oriented matroid of rank  can be obtained from a pseudosphere arrangement in

can be obtained from a pseudosphere arrangement in  .[9]

.[9]

Geometry

The theory of oriented matroids has influenced the development of combinatorial geometry, especially the theory of convex polytopes, zonotopes, and of configurations of vectors (arrangements of hyperplanes).[10] Many results—Carathéodory's theorem, Helly's theorem, Radon's theorem, the Hahn–Banach theorem, the Krein–Milman theorem, the lemma of Farkas—can be formulated using appropriate oriented matroids.[11]

Optimization

The theory of oriented matroids was initiated by R. Tyrrell Rockafellar to describe the sign patterns of the matrices arising through the pivoting operations of Dantzig's simplex algorithm; Rockafellar was inspired by Albert W. Tucker studies of such sign patterns in "Tucker tableaux". [12]

The theory of oriented matroids has led to break-throughs in combinatorial optimization. In linear programming, it was the language in which Robert G. Bland formulated his pivoting rule by which the simplex algorithm avoids cycles. Similarly, it was used by Terlaky and Zhang to prove that their criss-cross algorithms have finite termination for linear programming problems. Similar results were made in convex quadratic programming by Todd and Terlaky.[13] It has been applied to linear-fractional programming[14] quadratic-programming problems, and linear complementarity problems.[15][16][17]

Outside of combinatorial optimization, OM theory also appears in convex minimization in Rockafellar's theory of "monotropic programming" and related notions of "fortified descent".[18] Similarly, matroid theory has influenced the development of combinatorial algorithms, particularly the greedy algorithm.[19] More generally, a greedoid is useful for studying the finite termination of algorithms.

References

- ↑ Rockafellar 1969. Björner et alia, Chapters 1-3. Bokowski, Chapter 1. Ziegler, Chapter 7.

- ↑ Björner et alia, Chapters 1-3. Bokowski, Chapters 1-4.

- ↑ Because matroids and oriented matroids are abstractions of other mathematical abstractions, nearly all the relevant books are written for mathematical scientists rather than for the general public. For learning about oriented matroids, a good preparation is to study the textbook on linear optimization by Nering and Tucker, which is infused with oriented-matroid ideas, and then to proceed to Ziegler's lectures on polytopes.

- ↑ Björner et alia, Chapter 7.9.

- ↑ Björner et alia, Chapter 3.5

- ↑ Björner et alia, Chapter 7.9

- ↑ Björner et alia, Chapter 3.4

- ↑ Björner et alia, Chapter 3.6

- ↑ Björner et alia, Chapter 5.2

- ↑ Bachem and Kern, Chapters 1–2 and 4–9. Björner et alia, Chapters 1–8. Ziegler, Chapter 7–8. Bokowski, Chapters 7–10.

- ↑ Bachem and Wanka, Chapters 1–2, 5, 7–9. Björner et alia, Chapter 8.

- ↑ Rockafellar, R. T. (1969).

. In R. C. Bose and T. A. Dowling. Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications. The University of North Carolina Monograph Series in Probability and Statistics (4). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 104–127. MR 278972. PDF reprint.

. In R. C. Bose and T. A. Dowling. Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications. The University of North Carolina Monograph Series in Probability and Statistics (4). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 104–127. MR 278972. PDF reprint.

- ↑ Björner et alia, Chapters 8-9. Fukuda and Terlaky. Compare Ziegler.

- ↑ Illés, Szirmai & Terlaky (1999)

- ↑ Fukuda & Terlaky (1997)

- ↑ Fukuda & Terlaky (1997, p. 385)

- ↑ Fukuda & Namiki (1994, p. 367)

- ↑ Rockafellar 1984 and 1998.

- ↑ Lawler. Rockafellar 1984 and 1998.

Further reading

Books

- A. Bachem and W. Kern. Linear Programming Duality: An Introduction to Oriented Matroids. Universitext. Springer-Verlag, 1992.

- Björner, Anders; Las Vergnas, Michel; Sturmfels, Bernd; White, Neil; Ziegler, Günter (1999). Oriented Matroids. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications 46 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77750-6. Zbl 0944.52006.

- Bokowski, Jürgen (2006). Computational oriented matroids. Equivalence classes of matrices within a natural framework. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84930-2. Zbl 1120.52011.

- Lawler, Eugene (2001). Combinatorial Optimization: Networks and Matroids. Dover. ISBN 0-486-41453-1. Zbl 1058.90057.

- Evar D. Nering and Albert W. Tucker, 1993, Linear Programs and Related Problems, Academic Press. (elementary)

- R. T. Rockafellar. Network Flows and Monotropic Optimization, Wiley-Interscience, 1984 (610 pages); republished by Athena Scientific of Dimitri Bertsekas, 1998.

- Ziegler, Günter M., Lectures on Polytopes, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1994.

- Richter-Gebert, J. and G. Ziegler, Oriented Matroids, In Handbook of Discrete and Computational Geometry, J. Goodman and J.O'Rourke, (eds.), CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1997, p. 111-132.

Articles

- A. Bachem, A. Wanka, Separation theorems for oriented matroids, Discrete Math. 70 (1988) 303—310.

- Robert G. Bland, New finite pivoting rules for the simplex method, Math. Oper. Res. 2 (1977) 103–107.

- Jon Folkman and James Lawrence, Oriented Matroids, J. Combin. Theory Ser. B 25 (1978) 199—236.

- Fukuda, Komei; Terlaky, Tamás (1997). "Criss-cross methods: A fresh view on pivot algorithms". In Thomas M. Liebling and Dominique de Werra. Mathematical Programming: Series B 79 (1—3) (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co.). pp. 369–395. doi:10.1007/BF02614325. MR 1464775.

- Fukuda, Komei; Namiki, Makoto (March 1994). "On extremal behaviors of Murty's least index method". Mathematical Programming 64 (1): 365–370. doi:10.1007/BF01582581. MR 1286455.

- Illés, Tibor; Szirmai, Ákos; Terlaky, Tamás (1999). "The finite criss-cross method for hyperbolic programming". European Journal of Operational Research 114 (1): 198–214. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(98)00049-6. ISSN 0377-2217. PDF preprint.

- R. T. Rockafellar. The elementary vectors of a subspace of

, in Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications, R. C. Bose and T. A. Dowling (eds.), Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1969, 104-127.

, in Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications, R. C. Bose and T. A. Dowling (eds.), Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1969, 104-127. - Roos, C. (1990). "An exponential example for Terlaky's pivoting rule for the criss-cross simplex method". Mathematical Programming. Series A 46 (1): 79–84. doi:10.1007/BF01585729. MR 1045573.

- Terlaky, T. (1985). "A convergent criss-cross method". Optimization: A Journal of Mathematical Programming and Operations Research 16 (5): 683–690. doi:10.1080/02331938508843067. ISSN 0233-1934. MR 798939.

- Terlaky, Tamás (1987). "A finite crisscross method for oriented matroids". Journal of Combinatorial Theory. Series B 42 (3): 319–327. doi:10.1016/0095-8956(87)90049-9. ISSN 0095-8956. MR 888684.

- Terlaky, Tamás; Zhang, Shu Zhong (1993). "Pivot rules for linear programming: A Survey on recent theoretical developments". Annals of Operations Research (Springer Netherlands). 46–47 (1): 203–233. doi:10.1007/BF02096264. ISSN 0254-5330. MR 1260019. CiteSeerX: 10.1.1.36.7658.

- Michael J. Todd, Linear and quadratic programming in oriented matroids, J. Combin. Theory Ser. B 39 (1985) 105—133.

- Wang, Zhe Min (1987). "A finite conformal-elimination free algorithm over oriented matroid programming". Chinese Annals of Mathematics (Shuxue Niankan B Ji). Series B 8 (1): 120–125. ISSN 0252-9599. MR 886756.

On the web

- Ziegler, Günter (1998). "Oriented Matroids Today". The Electronic Journal of Combinatorics.

- Malkevitch, Joseph. "Oriented Matroids: The Power of Unification". Feature Column. American Mathematical Society. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

External links

- Komei Fukuda (ETH Zentrum, Zurich) with publications including Oriented matroid programming (1982 Ph.D. thesis)

- Tamás Terlaky (Lehigh University) with publications