Orbit equation

In astrodynamics an orbit equation defines the path of orbiting body  around central body

around central body  relative to

relative to  , without specifying position as a function of time. Under standard assumptions, a body moving under the influence of a force, directed to a central body, with a magnitude inversely proportional to the square of the distance (such as gravity), has an orbit that is a conic section (i.e. circular orbit, elliptic orbit, parabolic trajectory, hyperbolic trajectory, or radial trajectory) with the central body located at one of the two foci, or the focus (Kepler's first law).

, without specifying position as a function of time. Under standard assumptions, a body moving under the influence of a force, directed to a central body, with a magnitude inversely proportional to the square of the distance (such as gravity), has an orbit that is a conic section (i.e. circular orbit, elliptic orbit, parabolic trajectory, hyperbolic trajectory, or radial trajectory) with the central body located at one of the two foci, or the focus (Kepler's first law).

If the conic section intersects the central body, then the actual trajectory can only be the part above the surface, but for that part the orbit equation and many related formulas still apply, as long as it is a freefall (situation of weightlessness).

Central, inverse-square law force

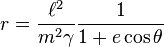

Consider a two-body system consisting of a central body of mass M and a much smaller, orbiting body of mass m, and suppose the two bodies interact via a central, inverse-square law force (such as gravitation). In polar coordinates, the orbit equation can be written as[1]

where  is the separation distance between the two bodies and

is the separation distance between the two bodies and  is the angle that

is the angle that  makes with the axis of periapsis (also called the true anomaly). The parameter

makes with the axis of periapsis (also called the true anomaly). The parameter  is the angular momentum of the orbiting body about the central body, and is equal to

is the angular momentum of the orbiting body about the central body, and is equal to  .[note 1] The parameter

.[note 1] The parameter  is the constant for which

is the constant for which  equals the acceleration of the smaller body (for gravitation,

equals the acceleration of the smaller body (for gravitation,  is the standard gravitational parameter,

is the standard gravitational parameter,  ). For a given orbit, the larger

). For a given orbit, the larger  , the faster the orbiting body moves in it: twice as fast if the attraction is four times as strong. The parameter

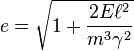

, the faster the orbiting body moves in it: twice as fast if the attraction is four times as strong. The parameter  is the eccentricity of the orbit, and is given by[1]

is the eccentricity of the orbit, and is given by[1]

where  is the energy of the orbit.

is the energy of the orbit.

The above relation between  and

and  describes a conic section.[1] The value of

describes a conic section.[1] The value of  controls what kind of conic section the orbit is. When

controls what kind of conic section the orbit is. When  , the orbit is elliptic; when

, the orbit is elliptic; when  , the orbit is parabolic; and when

, the orbit is parabolic; and when  , the orbit is hyperbolic.

, the orbit is hyperbolic.

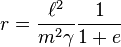

The minimum value of r in the equation is

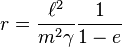

while, if  , the maximum value is

, the maximum value is

If the maximum is less than the radius of the central body, then the conic section is an ellipse which is fully inside the central body and no part of it is a possible trajectory. If the maximum is more, but the minimum is less than the radius, part of the trajectory is possible:

- if the energy is non-negative (parabolic or hyperbolic orbit): the motion is either away from the central body, or towards it.

- if the energy is negative: the motion can be first away from the central body, up to

- after which the object falls back.

If r becomes such that the orbiting body enters an atmosphere, then the standard assumptions no longer apply, as in atmospheric reentry.

Low-energy trajectories

If the central body is the Earth, and the energy is only slightly larger than the potential energy at the surface of the Earth, then the orbit is elliptic with eccentricity close to 1 and one end of the ellipse just beyond the center of the Earth, and the other end just above the surface. Only a small part of the ellipse is applicable.

If the horizontal speed is  , then the periapsis distance is

, then the periapsis distance is  . The energy at the surface of the Earth corresponds to that of an elliptic orbit with

. The energy at the surface of the Earth corresponds to that of an elliptic orbit with  (with

(with  the radius of the Earth), which can not actually exist because it is an ellipse fully below the surface. The energy increase with increase of a is at a rate

the radius of the Earth), which can not actually exist because it is an ellipse fully below the surface. The energy increase with increase of a is at a rate  . The maximum height above the surface of the orbit is the length of the ellipse, minus

. The maximum height above the surface of the orbit is the length of the ellipse, minus  , minus the part "below" the center of the Earth, hence twice the increase of

, minus the part "below" the center of the Earth, hence twice the increase of  minus the periapsis distance. At the top the potential energy is

minus the periapsis distance. At the top the potential energy is  times this height, and the kinetic energy is

times this height, and the kinetic energy is  . This adds up to the energy increase just mentioned. The width of the ellipse is 19 minutes times

. This adds up to the energy increase just mentioned. The width of the ellipse is 19 minutes times  .

.

The part of the ellipse above the surface can be approximated by a part of a parabola, which is obtained in a model where gravity is assumed constant. This should be distinguished from the parabolic orbit in the sense of astrodynamics, where the velocity is the escape velocity. See also trajectory.

Categorization of orbits

Consider orbits which are at one point horizontal, near the surface of the Earth. For increasing speeds at this point the orbits are subsequently:

- part of an ellipse with vertical major axis, with the center of the Earth as the far focus (throwing a stone, sub-orbital spaceflight, ballistic missile)

- a circle just above the surface of the Earth (Low Earth orbit)

- an ellipse with vertical major axis, with the center of the Earth as the near focus

- a parabola

- a hyperbola

Note that in the sequence above,  ,

,  and

and  increase monotonically, but

increase monotonically, but  first decreases from 1 to 0, then increases from 0 to infinity. The reversal is when the center of the Earth changes from apoapsis to periapsis (the other focus starts near the surface and passes the center of the Earth). We have

first decreases from 1 to 0, then increases from 0 to infinity. The reversal is when the center of the Earth changes from apoapsis to periapsis (the other focus starts near the surface and passes the center of the Earth). We have

Extending this to orbits which are horizontal at another height, and orbits of which the extrapolation is horizontal below the surface of the Earth, we get a categorization of all orbits, except the radial trajectories, for which, by the way, the orbit equation can not be used. In this categorization ellipses are considered twice, so for ellipses with both sides above the surface one can restrict oneself to taking the side which is lower as the reference side, while for ellipses of which only one side is above the surface, taking that side.

Notes

- ↑ There is a related parameter, known as the specific relative angular momentum,

. It is related to

. It is related to  by

by  .

.

References

See also

- Kepler's first law

- Circular orbit

- Elliptic orbit

- Parabolic trajectory

- Hyperbolic trajectory

- Rocket equation

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||