Chirality (chemistry)

A chiral molecule /ˈkaɪərəl/ is a type of molecule that has a non-superposable mirror image. The presence of an asymmetric carbon atom is often the feature that causes chirality in molecules.[1][2][3][4]

Achiral (not chiral) objects, such as molecules, are symmetrical, identical to their mirror image.

Human hands are perhaps the most universally recognized example of chirality: the left hand is a non-superposable mirror image of the right hand; no matter how the two hands are oriented, it is impossible for all the major features of both hands to coincide. This difference in symmetry becomes obvious if a left-handed glove is placed on a right hand. The term chirality is derived from the Greek word for hand, χειρ (kheir). It is a mathematical approach to the concept of "handedness".

In chemistry, chirality usually refers to molecules. Two mirror images of a chiral molecule are called enantiomers or optical isomers. Pairs of enantiomers are often designated as "right-" and "left-handed".

Molecular chirality is of interest because of its application to stereochemistry in inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry, physical chemistry, biochemistry, and supramolecular chemistry.

History

The term optical activity is derived from the interaction of chiral materials with polarized light. In solution, the (−)-form, or levorotary form, of an optical isomer rotates the plane of a beam of polarized light counterclockwise. The (+)-form, or dextrorotatory form, does the opposite. The property was first observed by Jean-Baptiste Biot in 1815,[5] and gained considerable importance in the sugar industry, analytical chemistry, and pharmaceuticals. Louis Pasteur deduced in 1848 that this phenomenon has a molecular basis.[6] Artificial composite materials displaying the analog of optical activity but in the microwave region were introduced by J.C. Bose in 1898,[7] and gained considerable attention from the mid-1980s.[8] The term chirality itself was coined by Lord Kelvin in 1894.[9] Different enantiomers or diastereomers of a compound were formerly called optical isomers due to their different optical properties.[10]

Symmetry

The symmetry of a molecule (or any other object) determines whether it is chiral. A molecule is achiral (not chiral) when an improper rotation, that is a combination of a rotation and a reflection in a plane, perpendicular to the axis of rotation, results in the same molecule - see chirality (mathematics). For tetrahedral molecules, the molecule is chiral if all four substituents are different.

A chiral molecule is not necessarily asymmetric (devoid of any symmetry element), as it can have, for example, rotational symmetry.

Naming conventions

By configuration: R- and S-

For chemists, the R / S system is the most important nomenclature system for denoting enantiomers, which does not involve a reference molecule such as glyceraldehyde. It labels each chiral center R or S according to a system by which its substituents are each assigned a priority, according to the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog priority rules (CIP), based on atomic number. If the center is oriented so that the lowest-priority of the four is pointed away from a viewer, the viewer will then see two possibilities: If the priority of the remaining three substituents decreases in clockwise direction, it is labeled R (for Rectus, Latin for right), if it decreases in counterclockwise direction, it is S (for Sinister, Latin for left).[11]

This system labels each chiral center in a molecule (and also has an extension to chiral molecules not involving chiral centers). Thus, it has greater generality than the D/L system, and can label, for example, an (R,R) isomer versus an (R,S) — diastereomers.

The R / S system has no fixed relation to the (+)/(−) system. An R isomer can be either dextrorotatory or levorotatory, depending on its exact substituents.

The R / S system also has no fixed relation to the D/L system. For example, the side-chain one of serine contains a hydroxyl group, -OH. If a thiol group, -SH, were swapped in for it, the D/L labeling would, by its definition, not be affected by the substitution. But this substitution would invert the molecule's R / S labeling, because the CIP priority of CH2OH is lower than that for CO2H but the CIP priority of CH2SH is higher than that for CO2H.

For this reason, the D/L system remains in common use in certain areas of biochemistry, such as amino acid and carbohydrate chemistry, because it is convenient to have the same chiral label for all of the commonly occurring structures of a given type of structure in higher organisms. In the D/L system, they are nearly all consistent - naturally occurring amino acids are all L, while naturally occurring carbohydrates are nearly all D. In the R / S system, they are mostly S, but there are some common exceptions.

By optical activity: (+)- and (−)- or d- and l-

An enantiomer can be named by the direction in which it rotates the plane of polarized light. If it rotates the light clockwise (as seen by a viewer towards whom the light is traveling), that enantiomer is labeled (+). Its mirror-image is labeled (−). The (+) and (−) isomers have also been termed d- and l-, respectively (for dextrorotatory and levorotatory). Naming with d- and l- is easy to confuse with D- and L- labeling and is therefore strongly discouraged by IUPAC.[12]

By configuration: D- and L-

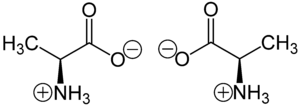

An optical isomer can be named by the spatial configuration of its atoms. The D/L system, not to be confused with the d- and l-system, see above, does this by relating the molecule to glyceraldehyde. Glyceraldehyde is chiral itself, and its two isomers are labeled D and L (typically typeset in small caps in published work). Certain chemical manipulations can be performed on glyceraldehyde without affecting its configuration, and its historical use for this purpose (possibly combined with its convenience as one of the smallest commonly used chiral molecules) has resulted in its use for nomenclature. In this system, compounds are named by analogy to glyceraldehyde, which, in general, produces unambiguous designations, but is easiest to see in the small biomolecules similar to glyceraldehyde. One example is the amino acid alanine, which has two optical isomers, and they are labeled according to which isomer of glyceraldehyde they come from. On the other hand, glycine, the amino acid derived from glyceraldehyde, has no optical activity, as it is not chiral (achiral). Alanine, however, is chiral.

The D/L labeling is unrelated to (+)/(−); it does not indicate which enantiomer is dextrorotatory and which is levorotatory. Rather, it says that the compound's stereochemistry is related to that of the dextrorotatory or levorotatory enantiomer of glyceraldehyde—the dextrorotatory isomer of glyceraldehyde is, in fact, the D- isomer. Nine of the nineteen L-amino acids commonly found in proteins are dextrorotatory (at a wavelength of 589 nm), and D-fructose is also referred to as levulose because it is levorotatory.

A rule of thumb for determining the D/L isomeric form of an amino acid is the "CORN" rule. The groups:

- COOH, R, NH2 and H (where R is the side-chain)

are arranged around the chiral center carbon atom. With the hydrogen atom away from the viewer, if the arrangement of the CO→R→N groups around the carbon atom is center is clockwise, then it is the D form.[13] If the arrangement is counter-clockwise, it is the L form. The L form is the usual one found in natural proteins. For most amino acids, the L form corresponds to an S absolute stereochemistry, but is R instead for certain side-chains.

Nomenclature

- Any non-racemic chiral substance is called scalemic.[14]

- A chiral substance is enantiopure or homochiral when only one of two possible enantiomers is present.

- A chiral substance is enantioenriched or heterochiral when an excess of one enantiomer is present but not to the exclusion of the other.

- Enantiomeric excess or ee is a measure for how much of one enantiomer is present compared to the other. For example, in a sample with 40% ee in R, the remaining 60% is racemic with 30% of R and 30% of S, so that the total amount of R is 70%.

Stereogenic centers

In general, chiral molecules have point chirality at a single stereogenic atom, which has four different substituents. The two enantiomers of such compounds are said to have different absolute configurations at this center. This center is thus stereogenic (i.e., a grouping within a molecular entity that may be considered a focus of stereoisomerism).

Normally when an atom has four different substituents, it is chiral. However in rare cases, two of the ligands differ from each other by being mirror images of each other. When this happens, the mirror image of the molecule is identical to the original, and the molecule is achiral. This is called pseudochirality.

A molecule can have multiple stereogenic centers without being chiral overall if there is a symmetry between the two (or more) stereocenters themselves. Such a molecule is called a meso compound.

It is also possible for a molecule to be chiral without having actual point chirality. Common examples include 1,1'-bi-2-naphthol (BINOL), 1,3-dichloro-allene, and BINAP, which have axial chirality, (E)-cyclooctene, which has planar chirality, and certain calixarenes and fullerenes, which have inherent chirality.

A form of point chirality can also occur if a molecule contains a tetrahedral subunit which cannot easily rearrange, for instance 1-bromo-1-chloro-1-fluoroadamantane and methylethylphenyltetrahedrane.

It is important to keep in mind that molecules have considerable flexibility and thus, depending on the medium, may adopt a variety of different conformations. These various conformations are themselves almost always chiral. When assessing chirality, a time-averaged structure is considered and for routine compounds, one should refer to the most symmetric possible conformation.

When the optical rotation for an enantiomer is too low for practical measurement, it is said to exhibit cryptochirality.

Even isotopic differences must be considered when examining chirality. Replacing one of the two 1H atoms at the CH2 position of benzyl alcohol with a deuterium (2H) makes that carbon a stereocenter. The resulting benzyl-α-d alcohol exists as two distinct enantiomers, which can be assigned by the usual stereochemical naming conventions. The S enantiomer has [α]D = +0.715°.[15]

The identity of the stereogenic atom

The stereogenic atom in chiral molecules is usually carbon, as in many biological molecules. However, it may also be a metal atom (as in many chiral coordination compounds), nitrogen, phosphorus, or sulfur.

| The chiral atom | Carbon | Nitrogen | Phosphorus (phosphates) | Phosphorus (phosphines) | Sulfur | Metal (type of metal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 stereogenic center | Serine, glyceraldehyde | Sarin, VX | Esomeprazole, armodafinil | Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) (ruthenium), cis-Dichlorobis(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) (cobalt), hexol (cobalt) | ||

| 2 stereogenic centers | Threonine, isoleucine | Tröger's base | Adenosine triphosphate | DIPAMP | Dithionous acid | |

| 3 or more stereogenic centers | Met-enkephalin, leu-enkephalin | DNA |

Properties of enantiomers

Normally, the two enantiomers of a molecule behave identically to each other. For example, they will migrate with identical Rf in thin layer chromatography and have identical retention time in HPLC. Their NMR and IR spectra are identical. However, enantiomers behave differently in the presence of other chiral molecules or objects. For example, enantiomers do not migrate identically on chiral chromatographic media, such as quartz or standard media that have been chirally modified. The NMR spectra of enantiomers are affected differently by single-enantiomer chiral additives such as EuFOD.

Chiral compounds rotate plane polarized light. Each enantiomer will rotate the light in a different sense, clockwise or counterclockwise. Molecules that do this are said to be optically active.

Characteristically, different enantiomers of chiral compounds often taste and smell differently and have different effects as drugs – see below. These effects reflect the chirality inherent in biological systems.

One chiral 'object' that interacts differently with the two enantiomers of a chiral compound is circularly polarised light: An enantiomer will absorb left- and right-circularly polarised light to differing degrees. This is the basis of circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Usually the difference in absorptivity is relatively small (parts per thousand). CD spectroscopy [16] is a powerful analytical technique for investigating the secondary structure of proteins and for determining the absolute configurations of chiral compounds, in particular, transition metal complexes. CD spectroscopy is replacing polarimetry as a method for characterising chiral compounds, although the latter is still popular with sugar chemists.

In biology

Many biologically active molecules are chiral, including the naturally occurring amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) and sugars. In biological systems, most of these compounds are of the same chirality: most amino acids are L and sugars are D. Typical naturally occurring proteins, made of L amino acids, are known as left-handed proteins, whereas D amino acids produce right-handed proteins.

The origin of this homochirality in biology is the subject of much debate.[17] Most scientists believe that Earth life's "choice" of chirality was purely random, and that if carbon-based life forms exist elsewhere in the universe, their chemistry could theoretically have opposite chirality. However, there is some suggestion that early amino acids could have formed in comet dust. In this case, circularly polarised radiation (which makes up 17% of stellar radiation) could have caused the selective destruction of one chirality of amino acids, leading to a selection bias which ultimately resulted in all life on Earth being homochiral.[18]

Enzymes, which are chiral, often distinguish between the two enantiomers of a chiral substrate. Imagine an enzyme as having a glove-like cavity that binds a substrate. If this glove is right-handed, then one enantiomer will fit inside and be bound, whereas the other enantiomer will have a poor fit and is unlikely to bind.

D-form amino acids tend to taste sweet, whereas L-forms are usually tasteless.[19] Spearmint leaves and caraway seeds, respectively, contain R-(–)-carvone and S-(+)-carvone - enantiomers of carvone.[20] These smell different to most people because our olfactory receptors also contain chiral molecules that behave differently in the presence of different enantiomers.

Chirality is important in context of ordered phases as well, for example the addition of a small amount of an optically active molecule to a nematic phase (a phase that has long range orientational order of molecules) transforms that phase to a chiral nematic phase (or cholesteric phase). Chirality in context of such phases in polymeric fluids has also been studied in this context.[21]

D-Amino Acid Natural Abundance

The relative abundances of each of the different D-isomers of several amino acids have recently been quantified by collecting experimentally reported data from the proteome across all organisms in the Swiss-Prot database. The D-isomers observed experimentally were found to occur very rarely as shown in the following table in the database of protein sequences containing over 187 million amino acids.[22]

| D-amino acid | # of Times Experimentally Observed |

|---|---|

| D-alanine | 664 |

| D-serine | 114 |

| D-methionine | 19 |

| D-phenylalanine | 15 |

| D-valine | 8 |

| D-tryptophan | 7 |

| D-leucine | 6 |

| D-asparagine | 2 |

| D-threonine | 2 |

However, the D-isomers are not uncommon as free amino acids. Humans have special enzymes to process then, D-amino acid oxidase and D-aspartate oxidase. D-glutamic acid, D-glutamin, and D-alanine are also extremely common at a part of the peptidoglycan layer in the bacterial cell wall. In addition, D-serine is a neurotransmitter, and produced in humans by serine racemase.

Inorganic chemistry

-cation-3D-balls.png)

Many coordination compounds are chiral. At one time, chirality was only associated with organic chemistry, but this misconception was overthrown by the resolution of a purely inorganic compound, hexol, by Alfred Werner. A famous example is tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) complex in which the three bipyridine ligands adopt a chiral propeller-like arrangement.[23] In this case, the Ru atom is the stereogenic center. The two enantiomers of complexes such as [Ru(2,2′-bipyridine)3]2+ may be designated as Λ (capital lambda, the Greek version of "L") for a left-handed twist of the propeller described by the ligands, and Δ (capital delta, Greek "D") for a right-handed twist – pictured.

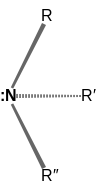

Chirality of compounds with a stereogenic "lone pair"

When a nonbonding pair of electrons, a lone pair, occupies space, chirality can result. The effect is pervasive in certain amines, phosphines,[24] sulfonium and oxonium ions, sulfoxides, and even carbanions. The main requirement is that aside from the lone pair, the other three substituents differ mutually. Chiral phosphine ligands are useful in asymmetric synthesis.

Chiral amines are special in the sense that the enantiomers can rarely be separated. The energy barrier for nitrogen inversion of the stereocenter is generally only about 30 kJ/mol, which means that the two stereoisomers rapidly interconvert at room temperature. As a result, such chiral amines cannot be resolved into individual enantiomers unless some of the substituents are constrained in cyclic structures as in Tröger's base.

See also

- Stereochemistry for overview of stereochemistry in general

- Supramolecular chirality

- Chirality (physics)

- Chirality (mathematics)

- Pfeiffer Effect

- Chemical chirality in popular fiction

References

- ↑ Organic Chemistry (4th Edition) Paula Y. Bruice.

- ↑ Organic Chemistry (3rd Edition) Marye Anne Fox ,James K. Whitesell.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Chirality".

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Superposability".

- ↑ Lakhtakia, A. (ed.) (1990). Selected Papers on Natural Optical Activity (SPIE Milestone Volume 15). SPIE.

- ↑ Pasteur, L. (1848). Researches on the molecular asymmetry of natural organic products, English translation of French original, published by Alembic Club Reprints (Vol. 14, pp. 1–46) in 1905, facsimile reproduction by SPIE in a 1990 book.

- ↑ Bose, J. C. (1898). On the rotation of plane of polarisation of electric waves by a twisted structure, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. (Vol. 63, pp. 146–152), facsimile reproduction by Wiley in a 2000 book.

- ↑ Ernest L. Eliel and Samuel H. Wilen (1994). The Sterochemistry of Organic Compounds. Wiley-Interscience.

- ↑ Ronald Bentley (1995). "From optical activity in quartz to chiral drugs: molecular handedness in biology and medicine.". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 38 (2): 188–229. PMID 7899056.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Optical isomers".

- ↑ Andrew Streitwieser and Clayton H. Heathcock (1985). Introduction to Organic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Macmillan Publishing Company.

- ↑ G.P. Moss: Basic terminology of stereochemistry ( Recommendations 1996); Pure Appl. Chem., 1996, Vol. 68, No. 12, p. 2205; doi:10.1351/pac199668122193

- ↑ "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". Pure Appl Chem 56 (5): 595–624. 1984.

- ↑ Infelicitous stereochemical nomenclatures for stereochemical nomenclature

- ↑ ^ Streitwieser, A., Jr.; Wolfe, J. R., Jr.; Schaeffer, W. D. (1959). "Stereochemistry of the Primary Carbon. X. Stereochemical Configurations of Some Optically Active Deuterium Compounds". Tetrahedron 6 (4): 338–344. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(59)80014-4.

- ↑ CD spectroscopy

- ↑ Uwe J. Meierhenrich (2008). Amino acids and the asymmetry of life. Springer, Heidelberg, Berlin, New York. ISBN 3-540-76885-8.

- ↑ , New Scientist, 2005.

- ↑ MobileReference (2008). Amino acids and the asymmetry of life. Springer, Heidelberg, Berlin, New York. ISBN 3-540-76885-8.

- ↑ Theodore J. Leitereg, Dante G. Guadagni, Jean Harris, Thomas R. Mon, and Roy Teranishi (1971). "Chemical and sensory data supporting the difference between the odors of the enantiomeric carvones". J. Agric. Food Chem. 19 (4): 785. doi:10.1021/jf60176a035.

- ↑ Srinivasarao, M. (1999). Chirality and Polymers, Current Opinion in Colloid and Interface Science (Vol. 4(5), pp. 369–376), 1999.

- ↑ Khoury, George A.; Baliban, Richard C.; and Christodoulos A. Floudas (2011). "Proteome-wide post-translational modification statistics: frequency analysis and curation of the swiss-prot database". Scientific Reports 1 (90). doi:10.1038/srep00090.

- ↑ von Zelewsky, A. "Stereochemistry of Coordination Compounds" John Wiley: Chichester, 1995. ISBN 047195599.

- ↑ Quin, L. D. A Guide to Organophosphorus Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, 2000. ISBN 0-471-31824-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chirality. |

- http://www.chirality2009.org/

- http://www.chemguide.co.uk/basicorg/isomerism/optical.html#top

- http://www.nature.com/horizon/chemicalspace/highlights/s5_nonspec1.html

- IUPAC nomenclature for amino acid configurations.

- Michigan State University's explanation of R/S nomenclature

- Chirality & Odour Perception at leffingwell.com

- Chirality & Bioactivity I.: Pharmacology

- Chirality and the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

| |||||||||||||||||