Operation Alpha Centauri

| Operation Alpha Centauri | |

|---|---|

| Part of South African Border War | |

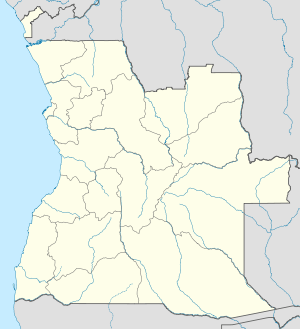

| Location | Angola Mavinga Jamba Cuito Cuanavale Operation Alpha Centauri (Angola)

|

| Objective | Artillery Bombardment and Ground Assault of Cuito Cuanavale |

| Date | 15–17 August 1986 |

| |||||

Operation Alpha Centauri (1986) was a military operation by the South African Defence Force during the South African Border War and Angolan Civil War.

Background

This aim of this operation was to stop a People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) advance on the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) "capital" of Jamba. Operation Alpha Centauri was developed out of a cancelled plan that had been modified to become Operation Southern Cross that occurred during July 1986.[1] Operation Southern Cross was not successful and therefore Operation Alpha Centauri called for a ground assault during August 1986 on the FAPLA town and airbase at Cuito Cuanavale.[2] Originally the plan called for a night attack by 32 Battalion and UNITA troops supported by artillery but the South African government decided that the attack would be carried out by UNITA and 32 Battalion would protect the SADF support troops and artillery.[3]

Order of Battle

Source: Nortje, Piet (2004). 32 Battalion. The Inside Story of South Africa's Elite Fighting Unit. p. 227.

South African Forces

32 Battalion

- Four rifle companies

- Support company (mortar, anti-aircraft, anti-tank and assault pioneer platoons)

120mm mortar platoon (61st Mechanised Battalion)

Valkiri MRL troop

G5 155mm artillery

Ratel 90 anti-tank squadron

Ystervark anti-aircraft platoon + one BRDM SA-9 system

UNITA forces

Two battalions (1500 men)

Angolan forces

- 13th Brigade

- 25th Brigade

Battle

The SADF troops assigned to the operation began their training for the assault on Cuito Cuanavale. Meanwhile supplies were being moved up to Mavinga, establishing on 15 July a logistics base for the operation. G5 artillery was then attached to the 32 Battalion and by the end of July the SAAF begun flying in the anti-aircraft systems directly into Mavinga.

On the 29 July, the South African government made the decision that UNITA would carry out the assault on Cuito and not 32 Battalion who would again be relegated to escort and protection duties of the SADF support troops and artillery. The plan now called for UNITA to first attack the 25th Brigade east of the town and river, drawing the tanks out of the town, then capturing the bridge over the river to the town. A day later, another UNITA brigade would attack the 13th Brigade in and around the town from the south.

By the 4 August the SADF units begun position themselves around Cuito Cuanavale. SADF operation headquarters was moved to 28 km east of Cuito, the artillery and two 32 Battalion companies 60 km east and further units in between the two. 32 Battalion reconnaissance units were based even closer, 4 km from the town and an engineer team was building a bridge just 7 km south of the town's easterly bridge. However the operation was postponed as the SADF awaited the arrival of UNITA's Jonas Savimbi.

By the 13 August, UNITA was still not ready but the SADF begun to move its troops closer to the town. The SADF HQ was now 4 km from the town, the G5 artillery moved in 30 km south east and the MRLs even closer at 14 km. The artillery bombardment would begin the operation on the early evening of the 14 August, but it did not. Now the SADF commanders were becoming nervous and threatened to withdraw their troops as the Angolan air-force increased its day flights trying to establish the whereabouts of the South African troops.[4] The bombardment finally began in the early evening of 15 August.

The UNITA brigade succeeded in briefly capturing the town of Cuito Cuanavale but during a counter-attack by FAPLA, and the failure of the second UNITA brigade to attack from the south, the UNITA forces were driven from the town. The bridge to the east of the town was then blown up. It was later established that UNITA had not succeeded in entering the airbase and the destruction of the airbase infrastructure was due to the SADF artillery and MRLs. By the 17 August, 32 Battalion began to withdraw back to Mavinga.

Vital artillery support

The G5 howitzer was used operationally for the first time by the SADF on 9 August 1986 during Operation Alpha Centauri. This operation lasted until 16 August 1986. One battery of G5s 42 Quebec battery out Potchefstroom (town) (4 field and 14 field the base for G5 and G6) at that time were stationed in South West Africa with 32 Battalion (a battery consists of eight guns) was employed in conjunction with one battery of multiple rocket launchers (MRL). The operation was an artillery attack against Cuban and FAPLA formations concentrating in Cuito Cuanavale for their 1986 offensive against UNITA. The 25th Cuban-FAPLA Brigade was situated east of Cuito Cuanavale near Tumpo. The 13th Brigade was situated in Cuito Cuanavale and the 8th Brigade operated between Menongue and Cuito Cuanavale, the former being a large logistics depot. Convoys regularly travelled from Menongue to supply Cuito Cuanavale.

In the weeks before the first assault, the 8 G5s were flown in darkness from Rundu to Mavinga (15°47'36 S 20°21'49 E) over 2 nights by South African Air Force Lockheed C-130 Hercules aircraft, whilst the remainder of the battery including the gun-tractors drove the distance. The heavy guns were difficult to drag through the sandy terrain and this avoided a significant part of the journey from the border to the target area.

The G5 assault began at last light, about 17h10. It was time for dinner, and the first shots were fired after most of the Brigade at Cuito Cuanavale went into the mess for supper. By 23h00 the back of the opposition was broken. Heavy fire was brought down upon the enemy in the first five hours resulting in large scale destruction. The G5s fired little during daytime, only when observation posts gave the OK.

The G5 battery, aka Quebec Battery, didn't move for the first three days, while they were shooting. This was a first for any artillery movement. Normally, after the guns fired, they would pack up and move, to avoid being fired upon.

It took the battery of G5s three days to break the offensive. Unita was left at Cuito Cuanavale, to keep control, and the battery of G5s were already retreating, when they had to turn around and go back, as Unita were chased out of Cuito Cuanavale by re-enforcements of Cuban and FAPLA forces. The battery of G5s then started another full-scale attack, taking out the re-enforcements as well. The battery of G5s then blew up a landing strip the Angolans used as an attack platform for their Migs, and an ammo-base, which exploded for hours, and burned for two-to-three days.

This destroyed the 1986 Cuban and FAPLA offensive against UNITA and showed the tremendous destructive force that lay within one battery of G5s. Owing to the long range and the accuracy with which the G5 could fire and the effect of the ammunition, authority was forced upon the enemy.

The battery of G-5s became known as the Ghost-Battery, because they couldn't be found by the opposition. As a result of the daylight activities of the MiG-23 jet fighters employed by the Cubans, artillery fire missions could only be executed at night. As it was the first time that the G5 was used operationally there was great cause for concern that the MiGs would spot the G5s. The spotter planes went over the G-5 battery everyday, but it must have looked like a dummy shelter. The MiGs were continuously in the air trying to locate the G5s and bombed the surrounding area at random in the hope of hitting the artillery.

The closest the bombs ever got to the battery of G-5s, was to hit the shelter the G-5s stayed at for 3 days, only 2 hours after the G-5s moved to a new shelter.The battery of G-5s battled for weeks to retreat out of Angola, because of Migs, and spotter planes, being in the air all the time.

This operation proved to the SADF that survival was possible despite an unfavourable air situation. As a result of the enemy's air superiority, great attention was given to passive defensive measures such as camouflage, track discipline and the concealment of movement.

Special techniques of concealment were practised beforehand which prevented the enemy from observing the artillery. Before the operation was undertaken these techniques of concealment were also tested under conditions similar to those that the artillery would experience during the operation. Another factor in favour of the artillery was the unprofessional manner in which the enemy employed its air force. The MiG fighters mostly flew at very high altitudes, making observation very difficult for the pilots. The apparent reason for this was to avoid being shot down by UNITA's Stinger anti-aircraft missiles. In addition, owing to the dryness of the season, the many bush fires in the area created a lot of dust and smoke in the air. During this operation approximately 2 500 multiple rocket launcher projectiles and approximately 4 500 G5 projectiles were used.

Aftermath

The SADF artillery and MRLs had succeeded in destroying most of the airbase's radar installations, its anti-aircraft installations and most of the fuel and ammunition depots.[5] UNITA succeeded in destroying Angolan aircraft and tanks. As would be seen in later battles, the SADF realised that UNITA was not capable of launching conventional attacks against FAPLA and the Cuban forces and would not be able to stop a combined offensive. This SADF operation had slowed down the Angolan, Cuban and Soviet troops planned offensive against UNITA but they would again regroup around the major towns close to Cuito and rearm for the future operations.

See also

References

- ↑ Nortje, Piet (2004). 32 Battalion. The Inside Story of South Africa's Elite Fighting Unit. p. 227.

- ↑ Nortje, Piet (2004). 32 Battalion. The Inside Story of South Africa's Elite Fighting Unit. p. 227.

- ↑ Nortje, Piet (2004). 32 Battalion. The Inside Story of South Africa's Elite Fighting Unit. p. 228.

- ↑ Nortje, Piet (2004). 32 Battalion. The Inside Story of South Africa's Elite Fighting Unit. p. 228-9.

- ↑ Steenkamp, Willem (1989). South Africa's Border War 1966–1989. p. 144.

Further reading

- Nortje, Piet (2004). 32 Battalion : the inside story of South Africa's elite fighting unit. Cape Town: Zebra Press. ISBN 1868729141.

- Scholtz, Leopold (2013). The SADF in the Border War 1966-1989. Cape Town: Tafelberg. ISBN 978-0-624-05410-8.

- Steenkamp, Willem (1989). South Africa's border war, 1966-1989. Gibraltar: Ashanti Pub. ISBN 0620139676.