Oneida people

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 45,000+ | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Onyota'aka, English, other Iroquoian dialects | |

| Religion | |

| Kai'hwi'io, Kanoh'hon'io, Kahni'kwi'io, Christianity, Longhouse, Handsome Lake, Other Indigenous Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, Tuscarora, and Cayuga |

The Oneida (Onę˙yóteˀ or Onayotekaono, meaning "Upright Stone Place, or standing stone", Thwahrù·nęʼ[1] in Tuscarora) are a Native American/First Nations people; they are one of the five founding nations of the Iroquois Confederacy in the area of upstate New York. The Iroquois call themselves Haudenosaunee ("The people of the longhouses") in reference to their communal lifestyle and the construction of their dwellings.

Historically the Oneida were believed to have emerged as a tribe in the 14th century; they inhabited approximately 6,000,000 acres (24,000 km2) of the area that later became central New York, particularly around Oneida Lake and Oneida and Madison counties.[2] The Great Swamp south of the lake was an important wetlands area with a rich habitat.[3] After the American Revolutionary War, they were forced to cede all but 300,000 acres (1,200 km2), and were later forced to cede more. Under federal and state pressure, many Oneida resettled in Wisconsin in the early 1800s. Others who had allied with the British had already migrated to Canada.

In the 21st century, the Oneida have four federally recognized, independent tribes groups with their own governments in New York and Wisconsin (following 19th-century forced removal by the United States), as well as Ontario, Canada. In the late twentieth century, three tribes filed land claim suits against New York State because of its unauthorized taking of land after the American Revolutionary War in a treaty that was never ratified by the United States Senate. The United States Supreme Court ruled that New York's action was unconstitutional, but settlement or compensation has not been determined.

The People of the Standing Stone

The name Oneida is the English mispronunciation of Onyota'a:ka. Onyota'a:ka means "People of the Standing Stone". The identity of the People of the Standing Stone is based on a legend in which the Oneida people were being pursued on foot by an enemy tribe. The Oneida people were chased into a clearing within the woodlands and suddenly disappeared. The enemy of the Oneida could not find them and so it was said that these people had turned themselves into stones that stood in the clearing. As a result, they became known as the People of the Standing Stone.

In older legends, the Oneida people identify as the "Big Tree People". Not much is written about this and Iroquoian elders would have to be consulted on the oral history of this identification. This may correspond to other Iroquoian notions of the Great Tree of Peace and the associated belief system of the people. Historians and anthropologists believe that the Iroquois Confederacy was formed about the early fifteenth century, among the five major Iroquoian-speaking peoples in New York.

Individuals born into the Oneida Nation are identified according to their spirit name, or what most outsiders now call an Indian name, their family unit, and their clan. The people have a matrilineal kinship system, in which children are born into the mother's clan and have their social status and identity within it. Their mother's elder brothers have important roles in raising them, as they belong to the same clan; their biological father, of a different clan, does not have the same status. Each gender and family unit within a clan has particular duties and responsibilities. Clan identities are derived from the Creation Story of the Onyota'a:ka peoples. The Oneida people identify with three clans: the Wolf, Turtle or Bear.

Although colonizing forces tried to assimilate the Native Americans of North America into their culture, the majority of the Oneida Nation who descend from the Oneida Settlement can still identify their clan. Historically, the Oneida took captives during warfare and absorbed them into their nation by adoption. As European colonists entered the area, the Oneida sometimes adopted Europeans as well and assimilated them. The act of adopting is primarily a responsibility of the Wolf clan, so many adoptees are identified as Wolf.

History

The Oneida inhabited a territory of about six million acres in central present-day New York, around Oneida Lake and in current Oneida and Madison counties.

American Revolution

The Iroquois had a long history of trade with Europeans, both French colonists from Canada and Dutch who reached out from settlements along the Hudson River, and later the English. Located further west from these areas of settlement, the Oneida did not encounter as many Europeans directly as did the Mohawk, the easternmost nation of the Iroquois. Until after the American Revolutionary War, most English and European settlement in the state generally went no further west than slightly beyond Little Falls, or the middle of the Mohawk Valley.

The Oneida and the five other tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy initially maintained a policy of neutrality in the American Revolution. This policy allowed the Confederacy increased leverage against both sides in the war, because they could threaten to join one side or the other in the event of any provocation. Neutrality quickly crumbled, as native villages got caught up in the conflict. The preponderance of the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga sided with the Loyalists and British, related both to long trading relationships, good relations with Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs who was located in New York, and hopes of restricting colonial encroachment into their territory.

Because of their proximity and relations with the rebel communities on the frontier, most Oneida favored the colonists. In contrast, the pro-British tribes were closer to the British stronghold at Fort Niagara and had trading relationships with English at Albany. The Oneida were influenced by the Protestant missionary Samuel Kirkland, who had spent several decades among them and through whom they had begun to form stronger cultural links to the colonists.

After being recruited by the Marquis de La Fayette, to whom they referred as the 'fearsome horseman',[4] the Oneida officially joined the rebel side and contributed in many ways to the war effort. Their warriors often scouted on offensive campaigns and to assess enemy operations around Fort Stanwix (also known as Fort Schuyler). The Oneida also facilitated communication between the Patriots and their Iroquois foes. In 1777 at the Battle of Oriskany, about fifty Oneida fought alongside the colonial militia. Many Oneida formed friendships with Philip Schuyler, George Washington, the Marquis de La Fayette, and other prominent Patriot leaders. These men recognized the Oneida contributions during and after the war. In the late 18th century, U.S. Senator Philip Schuyler declared, "sooner should a mother forget her children" than we should forget you.[5]

Individuals within the Oneida nation had the right to make their own choices as authority was decentralized, and a minority supported the British. As the war progressed and the Oneida position became more dire due to frontier fighting, this minority grew more numerous. When the important Oneida settlement at Kanonwalohale was destroyed by the Sullivan Campaign, numerous Oneida defected from the rebellion and relocated to Fort Niagara to live under British protection.

1794 Treaty of Canandaigua

The frontier fighting had been fierce and destructive and, after the war, not all settlers distinguished between allies and enemies. The Oneida were subject to retaliatory and other raids, and became displaced. In 1794 they, along with other Haudenosaunee nations, signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States. The four nations allied with the British had mostly migrated to Canada; the British had ceded their territory in New York without consultation, and the Iroquois were forced to cede their millions of acres to New York state.

As allies of the Patriots, the Oneida were granted 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) of their former 6,000,000 acres (24,000 km2) territory, primarily in New York; this was effectively the first Indian reservation in the new United States.[2] (Those who had allied with the British mostly went to Canada, where they settled with others of the Six Nations and styled Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation.) The end of the war released land hunger among veterans and pioneers from New England, and thousands migrated west into New York. Sometimes the federal government paid war veterans with land grants in the western part of the state. Upstate areas along Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River were also developed by European-American land speculators, many based in New York City.

By 1802 the Stockbridge-Munsee, a group of Mohegan and northern Lenape, and the Brotherton Indians (Lenape) of southern New Jersey, had migrated to join the Oneida on their land in New York, seeking to escape settler encroachment in their traditional homelands. The Oneida offered some land to these other tribes. The Brothertown Indians, a new tribe formed in New England in 1785 from several remnant tribes of Pequot and Mohegan-speaking peoples, also migrated west into New York and joined the others on Oneida land.

Subsequent treaties and actions by the State of New York drastically reduced the Oneida land to 32 acres (0.13 km2), as the state pressured all the Native American peoples to move west, away from European-American settlers. In the 1830s many of the Oneida relocated into the province of Upper Canada; others migrated to the territory of Wisconsin under federal pressure of Indian Removal, as the United States forced Indians west of the Mississippi River. Some remained in New York.

The Oneida formed the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, which later received federal recognition. The Brotherton Indians became absorbed into the Stockbridge-Munsee; these peoples and the Brothertown Indians also migrated to Wisconsin, where the latter two are also federally recognized tribes.

Recent litigation

In 1970 and 1974 the Oneida Indian Nation of New York, Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, and the Oneida Nation of the Thames filed suit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York to reclaim land taken from them by New York after the Revolutionary War, as it had been done without approval of a treaty by the United States Congress, as required by the US constitution. In 1998, the United States intervened in the lawsuits on behalf of the plaintiffs so the claim could proceed against New York State. The state had asserted immunity from suit under the Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution.[citation needed]

The defendants moved for summary judgment based on the U. S. Supreme Court's decision in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation (2005), in which the Court ruled that tribes could not re-establish sovereignty over lands they purchased on the open market, although the land was previously part of their reservation and traditional territory. It said the city and local governments had the power to tax such lands, but not necessarily the power to collect taxes.[2] The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit applied the Sherrill precedent, and reversed a $36.9 million damages award for 204 years of back rent, in Cayuga Indian Nation v. New York (2005).[6] Through these cases, the courts began to create new interpretations of law. On May 21, 2007, Judge Kahn dismissed the Oneida's possessory land claims and allowed the non-possessory claims to proceed.[7]

More recent litigation has formalized the split between, and defined the separate interests of the tribes of the Oneida who stayed in New York, and the Oneida who removed to Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Oneida tribe has sued to reacquire lands in their ancestral homelands of New York (now part of Madison County) as part of the settlement of the aforementioned litigation.[citation needed]

On 16 May 2013, New York State announced an agreement with the Oneida Indian Nation of New York, Oneida County, and Madison County to resolve all outstanding land claims and taxation litigation between the parties. The agreement requires approvals by the New York State Legislature, Oneida County, Madison County, United States Department of the Interior, New York State Attorney General, as well as judicial approval.[8][9]

Oneida Bands and First Nations today

- Oneida Indian Nation in New York

- Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, in and around Green Bay, Wisconsin

- Oneida Nation of the Thames in Southwold, Ontario

- Oneida at Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario

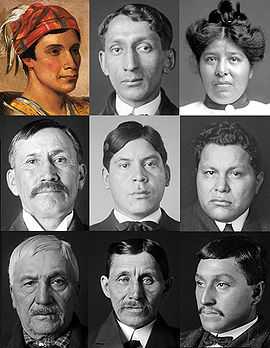

Notable Oneida

(Numerous people have been identified for needed articles on this list - please use RS)

Historical figures

- Ohstahehte, the original Oneida Chief who accepted the Message of the Great Law of Peace.

- Chief Skenandoah, Oneida leader during the American Revolution.

- Polly Cooper, leader, friend of Washington.

- Sally Ainse, diplomat, interpreter, and fur trader.

Entertainment, music and the arts

- Aaliyah, American recording artist, was of African-American and Oneida descent.

- Garrison Chrisjohn, X-Files actor.

- Graham Greene, actor

- Charlie Hill, comedian, entertainer.

- Joanne Shenandoah, award-winning singer and performer.

Sports

- Cody McCormick, Canadian professional ice hockey player for Colorado Avalanche.

- Gino Odjick, Canadian former professional ice hockey player.

Politics and government

- Carl J. Artman, Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

- Roland Chrisjohn, Director of Native Studies at St. Thomas University (New Brunswick).

- Ray Halbritter, Nation representative of the Oneida Nation of New York

- Lloyd L. House - Educator, first American Indian elected to the Arizona State Legislature.

- Purcell Powless, Tribal Chairman of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin

- Moses Schuyler, co-founder of the Oneida Nation of the Thames Settlement.

- Ernie Stevens Jr., Chairman of National Indian Gaming Association.

- Mary Winder, land claims activist.

Historians

- Alex Elijah I (Pine Tree Chief & Haudenosaunee Expert)

- Demus Elm, oral historian, Haudenosaunee expert.

- Evan John I, oral historian, traditional agriculture and horticulture expert.

- Loretta Metoxen, leader, Oneida historian.

- Venus Walker, oral historian, Haudenosaunee ceremonies expert.

Other fields

- Eileen Antone, academic, adult education expert.

- Harley Elijah Sr., President of Ironworkers Union Local 700.

- Lillie Rosa Minoka Hill, 20th-century Native American physician.

- Tehaliwaskenhas Bob Kennedy (Turtle Island)

See also

- County of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York State

- Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. County of Oneida

Notes

- ↑ Rudes, B. Tuscarora English Dictionary Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 City Of Sherrill V. Oneida Indian Nation Of N. Y

- ↑ Barbagallo, Tricia (June 1, 2005). "Black Beach: The Mucklands of Canastota, New York" (PDF). New York Archives. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ↑ Holbrook, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Joseph T. Glatthaar; James Kirby Martin (October 2, 2007). Forgotten Allies: The Oneida Indians and the American Revolution. Macmillan. p. ??.

- ↑ Cabranes, José A. (June 28, 2005). "partially dissenting pinion in CAYUGA INDIAN NATION OF NEW YORK *** v. GEORGE PATAKI ***". U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. 413 F.3d 266; 2005 U.S. App. LEXIS 12764. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- ↑ Kahn, Lawrence E. (May 21, 2007). "Memorand - Decision and order in Oneida Nation of New York, et al., v. State of New York, et al.". Albany, New York: U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York. Case 5:74-cv-00187-LEK-DRH. (reproduced at website of Upstate Citizens for Equality)

- ↑ "Governor Cuomo Announces Landmark Agreement Between State, Oneida Nation, and Oneida and Madison Counties". Albany, New York: Governor of New York. May 16, 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ↑ Toensing, Gale (May 16, 2013). "Oneida Nation and New York State Enter 'Historic' Revenue Sharing". Indian Country Today Media Network, LLC. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

References

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. and James Kirby Martin. Forgotten Allies: the Oneida Indians and the American Revolution. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006.

- Levinson, David. "An Explanation for the Oneida-Colonist Alliance in the American Revolution." Ethnohistory 23, no. 3. (Summer, 1976), pp. 265–289. Online via JSTOR (account required)

External links

- Official website of the Oneida Indian Nation of New York

- Official website of the Sovereign Oneida Nation of Wisconsin

- Oneida Indian Tribe of Wisconsin

- Official Website of the Oneida Nation of the Thames

- Oneida Nation of the Thames Radio Station Website

- Traditional Oneidas of New York, official website

- Barbagallo, Tricia (June 1, 2005). "Black Beach: The Mucklands of Canastota, New York" (PDF). New York Archives. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||