Olympic-class ocean liner

Belfast, Ireland, 6 March 1912: Titanic (right) moved out of the drydock to allow her sister Olympic to replace a damaged propeller blade. | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders: | Harland and Wolff, Belfast, Ireland[1] |

| Operators: |

|

| Built: | 1908–1914 |

| In service: | 1911–1935 |

| Planned: | 3 |

| Completed: | 3 |

| Lost: | Titanic (1912) and Britannic (1916) |

| Retired: | Olympic (1935) |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Titanic's dimensions used as all three vessels dimensions were different. |

| Tonnage: | 45,000 - 48,000 gross |

| Displacement: | app. 52,500 tons |

| Length: | 882 ft 9 in (269.06 m)[1] |

| Beam: | 92 ft 6 in (28.19 m)[1] |

| Height: | app. 60 ft (18 m) above water line |

| Draught: | 34 ft 7 in (10.54 m)[1] |

| Installed power: | 24 double-ended and 5 single-ended 15 bar Scotch marine boilers, tested to 30 bar. Two 4-cylinder reciprocating engines for the two outboard wing propellers. One low-pressure turbine for centre propeller. Together 50.000 HP nominal, 59.000 max.[2][3][4] |

| Propulsion: | Two bronze 3-blade wing propellers. One bronze 4-blade centre propeller. |

| Speed: | 21 kn (38.9 km/h; 24.2 mph); 23.5 kn (43.5 km/h; 27.0 mph) max.[1] |

| Capacity: | 3,295 passengers,officers,and crew[1] |

| Notes: | Approximate cost 7.5 million (USD) (approx. $177.56m at 2008 prices) |

The Olympic-class ocean liners were a trio of ocean liners built by the Harland & Wolff shipyard for the White Star Line in the early 20th century. They were Olympic, Titanic and Britannic. Two were lost early in their careers: Titanic sank on 15 April 1912 after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic, and Britannic sank on 21 November 1916, after hitting a mine laid by the German minelayer submarine U79 in a barrier off Kea during World War I. Olympic, the lead vessel, had a career spanning 24 years and was retired in 1934 and was sold for scrapping in 1935.

Although the two younger vessels did not have successful careers, they are among the most famous ocean liners ever built. Decorative elements of Olympic were purchased to adorn many places. Titanic's story has been adapted into many films and books, and Britannic has also inspired a movie of the same name.[5]

Origin and construction

The Olympic-class had its origins in the intense competition between the United Kingdom and Germany in the construction of the liners. The Norddeutscher Lloyd and HAPAG, the two largest German companies, were indeed involved in the race for speed and size in the late 19th century. The first in service for the Norddeutscher Lloyd was SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, which won the Blue Riband in 1897 [6] before being beaten by Deutschland of HAPAG in 1900.[7] Then followed the three vessels of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse: SS Kronprinz Wilhelm, SS Kaiser Wilhelm II and SS Kronprinzessin Cecilie all of whom were part of a "Kaiser class". In response to this, the Cunard Line of the UK ordered two vessels whose speed earned them the nickname "greyhounds of the seas:" Lusitania and Mauretania.[8] Mauretania kept the Blue Riband for more than twenty years, from 1909 to 1929.[9][10]

The White Star Line knew that their Big Four, a quartet of ships built for size and luxury [11] were no match for the Cunard's new liners in terms of speed. In 1907, J. Bruce Ismay, president of White Star and William J. Pirrie, director of the shipyard Harland & Wolff decided to build three vessels. And so, the Olympic-class ships were built to surpass rival Cunard's largest ships, Lusitania and Mauretania, in size and luxury. Olympic, along with Titanic and the soon to be built Britannic,[12] were intended to be the largest and most luxurious ships to operate on the North Atlantic, but not the fastest, as the White Star Line had already switched from high speed to size and luxury. The three vessels were designed by Thomas Andrews and Alexander Carlisle.[9]

Construction of Olympic started in December 1908 and Titanic in March 1909. The two ships were built side by side.[13] The construction of Britannic began in 1911 after the commissioning of Olympic and Titanic's launch. Following the sinking of Titanic, the two remaining vessels underwent many changes in their safety provisions.[14]

Specification

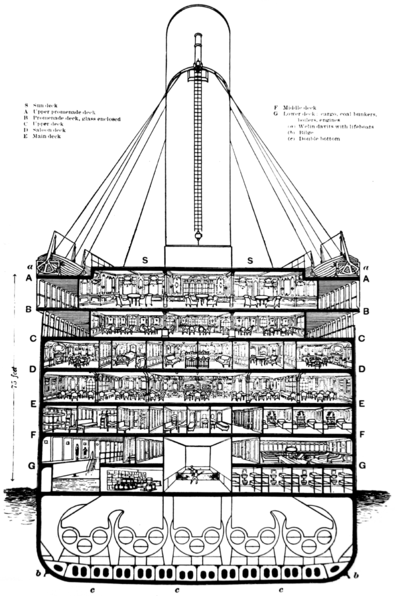

All three of the Olympic-class ships had eleven decks, eight of which were for passenger use. From top to bottom, the decks were:

- The Boat Deck, on which the lifeboats were positioned. The bridge and wheelhouse were at the forward end, in front of the captain's and officers' quarters. The bridge stood 8 feet (2.4 m) above the deck, extending out to either side so that the ship could be controlled while docking. The wheelhouse stood directly behind and above the bridge. The entrance to the First Class Grand Staircase and gymnasium were located midships along with the raised roof of the First Class lounge, while at the rear of the deck were the roof of the First Class smoke room and the relatively modest Second Class entrance. The wood-covered deck was divided into four segregated promenades; for officers, First Class passengers, engineers and Second Class passengers respectively. Lifeboats lined the side of the deck on both sides except in the First Class area, where there was a gap so that the view would not be blocked.[15][16]

- A Deck, also called the Promenade Deck, extended along the entire 546 feet (166 m) length of the superstructure. It was reserved only for First Class passengers and contained First Class cabins, the First Class lounge, smoke room, reading and writing rooms and Palm Court.[15] The promenade on Olympic was unenclosed along its whole length, whereas on Titanic and Britannic, the forward half was enclosed by a steel screen with sliding windows.[17]

- B Deck, the Bridge Deck, was the top weight-bearing deck and the uppermost level of the hull. More First Class passenger accommodation was located here with six staterooms (cabins) featuring their own private promenades. The Second Class smoking room and entrance hall were both located on this deck. The raised forecastle of the ship was forward of the Bridge Deck, accommodating Number 1 hatch (the main hatch through to the cargo holds), numerous pieces of machinery and the anchor housings. It was off limits to passengers and only accessible by the crew. Aft of the Bridge Deck was the raised Poop Deck, 106 feet (32 m) long, used as a promenade by Third Class passengers. The forecastle and Poop Deck were separated from the Bridge Deck by well decks.[18][19]

- C Deck, the Shelter Deck, was the uppermost deck to run uninterrupted from the ships' bow to stern. It included the two well decks; the aft one served as part of the Third Class promenade. Crew cabins were located under the forecastle and Third Class public rooms were situated under the Poop Deck. In between were the majority of First Class cabins and the Second Class library.[18][20]

- D Deck, the Saloon Deck, was dominated by three large public rooms – the First Class Reception Room, the First Class Dining Saloon and the Second Class Dining Saloon. An open space was provided for Third Class passengers. First, Second and Third Class passengers had cabins on this deck, with berths for firemen located in the bow. It was the highest deck reached by the ships' watertight bulkheads (though only by eight of the fifteen bulkheads).[18][21]

- E Deck, the Upper Deck, was predominantly a passenger accommodation for all three classes as well as berths for cooks, seamen, stewards and trimmers. Along its length ran a long passageway nicknamed Scotland Road by the crew, in reference to a famous street in Liverpool.[18][22]

- F Deck, the Middle Deck, was the last complete deck and predominantly accommodated Third Class passengers. There were also some Second Class cabins and crew accommodation. The Third Class dining saloon was located here, as were the swimming pool and Turkish bath.[18][22]

- G Deck, the Lower Deck, was the lowest complete deck to accommodate passengers, and had the lowest portholes, protruding above the waterline. The squash court was located here along with the travelling post office where mail clerks sorted letters and parcels so that they would be ready for delivery when the ship docked. Food was also stored here. The deck was interrupted at several points by orlop (partial) decks over the boiler, engine and turbine rooms.[18][23]

- The Orlop decks and the Tank Top were at the lowest level of the ship, below the waterline. The orlop decks were used as cargo space, while the Tank Top – the inner bottom of the ship's hull – provided the platform on which the ship's boilers, engines, turbines and electrical generators were housed. This part of the ship was dominated by the engine and boiler rooms, areas which were generally never seen by passengers. They were connected with higher levels of the ship by flights of stairs; twin spiral stairways near the bow gave access up to D Deck.[18][23]

Propulsion was achieved through three propellers: two outboard or wing propellers had three blades, while the central propeller had four. The two lateral propellers were powered by reciprocating steam triple expansion, while the central shaft was driven by a steam turbine.[24] All power on board was derived from a total of 29 coal-fired steam boilers in six compartments. However, Olympic's boilers were adapted for firing by oil at the end of the First World War,[25] which reduced the number of engine crew required from 350 to 60.[26]

The vessels were 269 metres (883 ft) long, displaced approx. 66,000 tons, and their tonnage surrounded 46,000 GRT.[27] Olympic, originally the smallest of the three, became the biggest British built ship ever constructed after her refit in 1912, until the commissioning of RMS Queen Mary in 1936.[28] All three vessels sported four funnels, with the fourth being a dummy which was used for ventilation purposes. Smoke from the galleys and Smoking Room fireplaces was exhausted through a chimney up the forward portion of this funnel. On the one hand it was a decoration to establish a symmetry in the ships' profile, on the other hand, acting as a huge ventilation shaft, it prevented the large amount of ventilation cowls on deck as on Cunard's Lusitania and Mauretania.[29]

Sixty-four lifeboats were the number possible to be added to each ships.[30] However, only 20 boats were installed on Olympic and Titanic to avoid cluttering the deck and provide more space for passengers. Shipbuilders of the era envisaged the ocean liner itself as the ultimate lifeboat and therefore imagined that a lifeboat's purpose was that of a ferry between a foundering liner and a rescue ship. Despite the low number of lifeboats, both Olympic and Titanic exceeded Board of Trade regulations of the time.[31] Following the sinking of Titanic, more lifeboats were added to Olympic (some lifeboats might even have been from the foundered Titanic[30]). Britannic, meanwhile, was equipped with eight special large davits to be able to launch many lifeboats at the same time.

Features

The Grand Staircase, only built for Olympic-Class Liners.

The three vessels had several levels of passenger accommodation, with slight variations between the ships. However, no class was neglected. The first class passengers enjoyed luxurious cabins, some were equipped with bathrooms. The two most luxurious even included a private promenade deck.[lower-alpha 1] There were also large dining rooms, a lavish Grand Staircase built only for the Olympic-class ships,[32] a Georgian-style smoking room, a Cafe Veranda decorated with palm trees,[33] a swimming pool, Turkish bath,[34] gymnasium,[35] and several other places for meals and entertainment.

The second class also included a smoking room, a library, a spacious dining room, and an elevator. Britannic's second class also featured a gymnasium.[36]

Finally, the third-class passengers enjoyed reasonable accommodation compared to other ships, if not up to the second and first classes. Instead of large dormitories offered by most ships of the time, the third-class passengers of the Olympic-class lived in cabins containing two to ten bunks. The class also had a smoking room, a common area, and a dining room. Britannic provided third-class passengers more comfort than its two sister ships.[37]

Careers

Olympic

Olympic was launched on 20 October 1910[38] and commissioned on 14 June 1911.[39] She made her maiden voyage on 14 June 1911. On September 20 of the same year, under Edward J. Smith, she collided with the cruiser HMS Hawke in the port of Southampton, leading to her repair back at Harland and Wolff.[40] When RMS Titanic sank, the Olympic was on her way across the Atlantic just in the opposite direction. She was able to receive a distress call from Titanic but too far away to reach her before she sank.[41] After the sinking of Titanic, Olympic underwent a number of refinements to improve her safety. She then resumed her commercial service.

During the First World War, the ship served as a troop transport. On 12 May 1918, she rammed and sank the German submarine U-103.[42] Once placed back in the commercial service during 1920, she crossed the Atlantic with two ships seized from Germany, Majestic and Homeric.[28] In 1934, she again sank a ship by a collision with the Nantucket Lightship LV-117, causing the death of the four occupants; three more died later.[43]

Following the merger of White Star Line and Cunard Line in 1934, Olympic was taken out of service in 1935, and scrapped between 1935 & 1937.

Titanic

Titanic was launched on 31 May 1911,[44] and her commissioning was slightly delayed due to ongoing repairs of Olympic.[45] The ship left the port of Southampton 10 April 1912 for her maiden voyage, narrowly avoiding a collision with SS New York, a ship moored in the port pulled by the propellers of Titanic. After a stopover at Cherbourg, France and another in Queenstown, Ireland, she sailed into the Atlantic with 2,200 passengers on board (a total capacity of 3,500), under the command of Captain Edward J. Smith headed for New York City. The crossing took place without major incident until Sunday, 14 April at 23:40.[46]

Titanic struck an iceberg at 41°46′N 50°14′W / 41.767°N 50.233°W.[47] while sailing about 400 miles south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland shortly before midnight. The strike and the resulting shock sheared the rivets, thus opening a leak in the hull below the waterline. This caused the first five compartments to be flooded with flooding in a sixth compartment controlled by the pumps; the ship could only stay afloat with four compartments flooded. The Titanic sank 2 hours and 40 minutes after the collision. There not being enough lifeboats for all of the passengers,[30] 1,517 of the 2,223 people on board died, making it one of the deadliest peacetime maritime disasters in history.

Britannic

Britannic was launched on 26 February 1914 at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast and fitting out began.[48] In August 1914, before Britannic could commence transatlantic service between New York and Southampton, World War I began. Immediately, all shipyards with Admiralty contracts were given top priority to use available raw materials. All civil contracts (including the Britannic) were slowed down.

On 13 November 1915, Britannic was requisitioned as a hospital ship from her storage location at Belfast. Repainted white with large red crosses and a horizontal green stripe, she was renamed HMHS (His Majesty's Hospital Ship) Britannic.[48]

.jpg)

08:12 am on 21 November 1916, The HMHS Britannic struck a mine[lower-alpha 2] at 37°42′05″N 24°17′02″E / 37.70139°N 24.28389°E,[49] and sank. 1,036 people were saved. Thirty men lost their lives in the disaster. One survivor, nurse Violet Jessop was notable as having also survived the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912, and had also been on board RMS Olympic, when it collided with the HMS Hawke in 1911. The Britannic was the largest ship lost during World War I, but her sinking did not receive the same attention as the sinking of her sister, Titanic, and the sinking of the Cunard superliner Lusitania, when she was sunk by a torpedo in the Irish Sea.[50]

Legacy

Wrecks and expeditions

When Titanic sank in 1912 and Britannic sank in 1916, their sinkings did not receive the same attention, due to the death toll (1,517 on Titanic and 30 on Britannic). Because the exact position of the sinking of the Britannic is known and the location is shallow, the wreck was discovered relatively easily in 1975.[51] Titanic, however, drew everyone's attention in 1912. After several attempts, the wreck was finally located by Jean-Louis Michel of Ifremer and Robert Ballard following a secret mission for the U.S. Navy.[52] The discovery of the wreck occurred on 1 September 1985, at 25 kilometres from the position given of the sinking. The wreck lies about 4,000 metres deep, broken in two. The bow is relatively well preserved, but the stern partially imploded, and to a large extent disintegrated during the descent and impact on the seabed.[lower-alpha 3]

The wreck of Britannic was discovered in 1975 by Jacques-Yves Cousteau. It has a large tear in the front caused by the bend of the bow when the ship rolled over. She has been, after the discovery, regularly seen as part of many other expeditions. In contrast to Titanic, which lies at the very bottom of the North Atlantic and is being fed on by iron-eating bacteria, the current wreck of Britannic is in remarkably good condition, and is much more accessible than her infamous sister. Many external structural features are still intact, including her huge propellers, and a great deal of her superstructure and hull.[53]

Cultural heritage

Museums and exhibitions pay tribute to the ships, and the two tragedies have inspired many movies, novels, and even musicals and video games.

When decommissioned, Olympic was previously set to be converted into a floating hotel,[54] but the project was canceled. However, its decorative elements were auctioned. The First Class Lounge and part of the Aft Grand Staircase, can be found in the White Swan Hotel, in Alnwick, Northumberland, England. The à la carte restaurant of Olympic is now restored on the Celebrity Millennium.[55]

Replicating the class

Several attempts have been made to make new ships based on the Olympic-class, the most recent - the Titanic II - started in 2012 by Australian businessman Clive Palmer.

Notes

- ↑ This last provision was a novelty on board Titanic.

- ↑ The hypothesis of the sinking caused by a mine was the one that had been accepted by the inquiry following the sinking. However, it's possible that the sinking was caused by a torpedo (Accessed March 21, 2009)

- ↑ On the contrary to the bow, the stern of the ship was not filled with water when it sank, and imploded as a result of the air.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Maritimequest: Titanic's Data

- ↑ "Mark Chirnside's Reception Room: Olympic, Titanic & Britannic: Olympic Interview, January 2005". Markchirnside.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ↑ "http://www.titanicology.com/Titanica/TitanicsPrimeMover.htm". Retrieved September 2013.

- ↑ "http://www.cityofart.net/bship/boiler_scotch.html". Retrieved September 2013.

- ↑ "Britannic (2000) (TV)". Imdb.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Le Goff 1998, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Le Goff 1998, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Le Goff 1998, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Othfors, Daniel. "Olympic". The Great Ocean Liners. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

- ↑ Le Goff 1998, p. 70.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 11.

- ↑ Origins Of The Olympic Class, RMS Olympic Archive. Retrieved August 8, 2009

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 14.

- ↑ Piouffre 2009, p. 307.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 47.

- ↑ Gill 2010, p. 229.

- ↑ Marriot, Leo (1997). TITANIC. PRC Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85648-433-5.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 48.

- ↑ Gill 2010, p. 232.

- ↑ Gill 2010, p. 233.

- ↑ Gill 2010, p. 235.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gill 2010, p. 236.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Gill 2010, p. 237.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 30.

- ↑ Le Goff 1998, p. 37.

- ↑ Olympic Returns To Passenger Service, RMS Olympic Archive. Retrieved August 8, 2009

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 319.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Chirnside 2004, p. 308.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. .

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 (French) Les canots de sauvetage, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved July 29, 2009

- ↑ Parks Stephenson. Retrieved June 12, 2011

- ↑ (French) Les escaliers de 1 Classe, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved July 30, 2009

- ↑ (French) La Vie à bord du Titanic, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved July 30, 2009

- ↑ (French) Les Bains Turcs et la Piscine, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved July 30, 2009

- ↑ (French) Le Gymnase, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved July 30, 2009

- ↑ HMHS Britannic -"The forgotten Sister", retrieved 2012-04-12

- ↑ Third class areas, Hospital Ship Britannic. Retrieved July 30, 2009

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 47.

- ↑ Piouffre 2009, p. 69.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Paul Chack, Jean-Jacques Antier, Histoire maritime de la Première Guerre mondiale, France – Empire, 1992, p. 778

- ↑ (French) Le RMS Olympic, L'histoire du RMS Olympic, RMS Titanic et HMHS Britannic. Retrieved 8 August 2009

- ↑ Piouffre 2009, p. 60.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 135.

- ↑ (French) Chronologie d'un naufrage, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved 10 August 2009

- ↑ Question No. 25 - When and where did the collision occur?, RMS Titanic, Inc. Retrieved July 6, 2007

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Chirnside 2004, p. 240.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ "PBS Online – Lost Liners – Britannic". PBS. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ (French) L'Olympic et le Britannic, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved 3 August 2009

- ↑ Gérard Piouffre, Le Titanic ne répond plus, Larousse, 2009, p. 296

- ↑ (English) The Wreck, Hospital Ship Britannic. Retrieved August 3, 2009

- ↑ (English) Mark Chirnside interview, january 2005, Mark Chirnside's Reception Room. Retrieved August 4, 2009

- ↑ Millennium, Celebrity Cruises. Retrieved August 4, 2009

Sources

- Chirnside, Mark (2004). The Olympic-Class Ships. Stroud, England: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2868-0.

- Gill, Anton (2010). Titanic : the real story of the construction of the world's most famous ship. Channel 4 Books. ISBN 978-1-905026-71-5.

- Hutchings, David F.; de Kerbrech, Richard P. (2011). RMS Titanic 1909–12 (Olympic Class): Owners' Workshop Manual. Sparkford, Yeovil: Haynes. ISBN 978-1-84425-662-4.

- Le Goff, Olivier (1998). Les Plus Beaux Paquebots du Monde (in French). Solar. ISBN 978-2-03-584196-4.

- Piouffre, Gérard (2009). Le Titanic ne répond plus (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-263-02799-4.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olympic class ocean liners. |

- McCluskie, Tom; Sharpe, Michael; Marriott, Leo (1998). Titanic & Her Sisters. ISBN 978-1-57145-175-0.

| ||||||||