Nyctosaurus

| Nyctosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 85–84.5Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

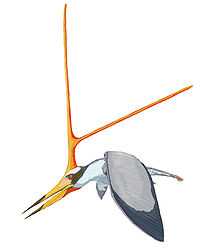

| Carnegie Museum specimen of N. gracilis, CM 11422 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Family: | †Nyctosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Nyctosaurinae Nicholson & Lydekker, 1889 |

| Genus: | †Nyctosaurus Marsh, 1876 |

| Type species | |

| Pteranodon gracilis Marsh, 1876 | |

| Species | |

|

N. gracilis (Marsh, 1876 [originally Pteranodon]) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Nyctodactylus Marsh, 1881 | |

Nyctosaurus is a genus of pterodactyloid pterosaur, the remains of which have been found in the Niobrara Formation of the mid-western United States, which, during the late Cretaceous Period, was covered in an extensive shallow sea. The genus Nyctosaurus has had numerous species referred to it, though how many of these may actually be valid requires further study. At least one species possessed an extraordinarily large antler-like cranial crest.[1]

Description

Nyctosaurus was similar in anatomy to its close relative and contemporary, Pteranodon. It had relatively long wings, similar in shape to modern seabirds. However, it was smaller overall than Pteranodon, with an adult wingspan of 2 meters (6.6 ft)[1] and a maximum weight of about 1.86 kg. The overall body length was 37 cm.[2] Some specimens preserve a distinctive crest, at least 55 cm tall in old adults, relatively gigantic compared to the rest of the body and over three times the length of the head. The crest is composed of two long, grooved spars, one pointed upward and the other backward, arising from a common base projecting up and back from the back of the skull. The two spars were nearly equal in length, and both were nearly as long or longer than the total length of the body. The upward-pointing crest spar was at least 42 cm long (1.3 ft) and the backward-pointing spar was at least 32 cm long (1 ft).[1]

The jaws of Nyctosaurus were long and extremely pointed. The jaw tips were thin and needle sharp, and are often broken off in fossil specimens, giving the appearance that one jaw is longer than the other, though in life they were probably equal in length.[1]

Nyctosaurus is the only pterosaur to have lost its clawed "fingers", with the exception of the wing finger (of which however the fourth phalanx was lost),[1] which is likely to have impaired its movement on the ground, leading scientists to conjecture that it spent almost all of its time on the wing and rarely landed. In particular, the lack of claws with which to grip surfaces would have made climbing or clinging to cliffs and tree trunks impossible for Nyctosaurus.

Biology

Life history

Nyctosaurus, like its relative Pteranodon, appears to have grown very rapidly after hatching. Fully adult specimens are no larger than some immature specimens such as P 25026 (pictured below), indicating that Nyctosaurus went from hatching to adult size (with wingspans of 2 m or more) in under a year. Some sub-adult specimens have been preserved with their skulls in nearly pristine condition, and lack any trace of a head crest, indicating that the distinctively large crest only began to develop after the first year of life. The crest may have continued to grow more elaborate as the animal aged, though no studies have examined the age of the fully adult, large-crested specimens. These individuals may have been 5 or even 10 years old at the time of their deaths.[1]

Crest function

Only five relatively complete Nyctosaurus skulls have been found. Of those, one is juvenile and does not possess a crest (specimen FMNH P 25026), and two are more mature and may show signs of having had a crest but are too badly crushed to say for sure (FHSM 2148 and CM 11422). Two specimens (KJ1 and KJ2) described in 2003, however, preserved an enormous double-pronged crest.[1]

A few scientists had initially hypothesized that this crest, which resembles an enormous antler, may have supported a skin "headsail" used for stability in flight. While there is no fossil evidence for such a sail, studies have shown that a membranous attachment to the bony crest would have imparted aerodynamic advantages.[3] However, in the actual description of the fossils, paleontologist Christopher Bennett argued against the possibility of a membrane or soft tissue extension to the crest. Bennett noted that the edges of each prong were smooth and rounded, and showed no evidence for any soft-tissue attachment points. He also compared Nyctosaurus with large-crested tapejarids, which do preserve soft tissue extensions supported by prongs, and showed that in those species, the attachment points were obvious, with jagged edges where the transition from bone to soft tissue occurred. Bennett concluded that the crest was most likely used solely for display, citing similar structures in modern animals.[1] The 2009 study by Xing and colleagues testing the aerodynamics of the giant crest with a "headsail" also tested the aerodynamics of the same crest with no sail, and found that it added no significant negative factors, so a crest with no headsail would not have hindered normal flight.[3] It is more likely that the crest acted mainly for display, and that any aerodynamic effects it may have had were secondary. Bennett also argued that the crest was probably not a sexually dimorphic character, as in most crested pterosaurs, including the related Pteranodon, both sexes are crested and it is only the size and shape of the crest that differs. The apparently non-crested Nyctosaurus specimens therefore probably came from sub-adults.[1]

The function of a very large headcrest such as the one possessed by Nyctosaurus is still a great mystery. It is theorized that a headsail would be able to harness the dynamic winds and add power to its flight. When it was in contact with water, whether skimming the water with its beak, dragging its wings, at rest or some combination of the like, the areas of surface contact would function like the keel of a boat pushing against the water medium and controlling its course. The loss of digits I, II, and III further streamlined the wing and support the use of sailing in some form.

Wing loading and speed

Sankar Chatterjee and R.J. Templin used estimates based on complete Nyctosaurus specimens to determine weight and total wing area, and to calculate its total wing loading. They also estimated its total available flight power based on estimated musculature. Using these calculations, they estimated the cruising speed of Nyctosaurus gracilis as 9.6 meters/second (34.5 kilometers/hour or 21.4 miles/hour).[2]

Ecology

All known Nyctosaurus fossils come from the Smokey Hills Chalk of Kansas, part of the Niobrara Formation. Specifically, they are found only within a narrow zone characterised by the abundance of ammonite fossils belonging to the species Spinaptychus sternbergi. These limestone deposits were laid down during a marine regression of the Western Interior Seaway that lasted between 85 and 84.5 million years ago. Therefore, Nyctosaurus was a relatively short-lived species, unlike its relative Pternodon, which is found throughout almost all of the Niobrara layers into the overlying Pierre Shale Formation, and existed between 88 and 80.5 million years ago.[4]

The ecosystem preserved in this zone was unique in its abundance of vertebrate life. Nyctosaurus shared the sky with the bird Ichthyornis and with Pteranodon longiceps, though the second Niobrara Pteranodon species, P. sternbergi, had disappeared from the fossil record by this point. In the waters of the Western Interior Seaway below swam mosasaurs (Clidastes, Ectenosaurus and Tylosaurus), the flightless diving bird Parahesperornis, and a wide variety of fish, including swordfish-like Protosphyraena, the predatory Xiphactinus and the shark Cretolamna.[4]

Discovery and species

The first Nyctosaurus fossils were described in 1876 by Othniel Charles Marsh, based on fragmentary material, holotype YPM 1178, from the Smoky Hill River site in Kansas. Marsh referred the specimen to a species of his new genus Pteranodon, as Pteranodon gracilis.[5] Later that year, Marsh reclassified the species in its own genus, which he named Nyctosaurus, meaning "night lizard" or "bat lizard", in reference to the wing structure somewhat paralleling those of bats.[6] In 1881, Marsh incorrectly assumed the name was preoccupied and changed it into Nyctodactylus, which thus is now a junior synonym.[7] In 1902, Samuel Wendell Williston described the most complete skeleton then known (P 25026) discovered in 1901 by H. T. Martin. In 1903, Williston named a second species, N. leptodactylus, but this is today considered identical to N. gracilis.

In 1953, Llewellyn Ivor Price named a partial humerus, DGM 238-R found in Brazil, N. lamegoi; the specific name honours the geologist Alberto Ribeiro Lamego. This species has an estimated wingspan of four metres; it is today generally considered to be a form different from Nyctosaurus, but has not yet been assigned its own genus name.[1] [8] [9]

In 1972 a new skeleton, FHSM VP-2148, in 1962 discovered by George Fryer Sternberg, was named N. bonneri; it is today generally seen as identical to N. gracilis.[1]

In 1978 Gregory Brown prepared the most complete Nyctosaurus skeleton currently known, UNSM 93000.[citation needed]

In 1984 Robert Milton Schoch renamed Pteranodon nanus (Marsh 1881), "the dwarf",[7] Nyctosaurus nanus. The question of this species validity is currently pending further study.[1]

In the early 2000s, Kenneth Jenkins of Ellis, Kansas collected two specimens of Nyctosaurus which were the first to demonstrate conclusively that not only was this species crested, the crest in mature specimens was very large and elaborate. The specimens were purchased by a private collector in Austin, Texas. Despite being in private hands rather than a museum collection, paleontologist Chris Bennett was able to study the specimens and gave them the manuscript reference numbers KJ1 and KJ2 (for Kenneth Jenkins). Bennett published a description of the specimens in 2003. Despite the unusual crests, the specimens were otherwise indistinguishable from other specimens of Nyctosaurus. However, the then-currently named species were extremely similar and Bennett declined to refer them to a specific one pending further study of the differences, or lack therof, between species of Nyctosaurus.[1]

See also

- List of pterosaurs

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 Bennett, S.C. (2003). "New crested specimens of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Nyctosaurus." Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 77: 61-75.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chatterjee, S. and Templin, R.J. (2004). Posture, Locomotion, and Paleoecology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society of America, 64 pp. ISBN 0-8137-2376-0, ISBN 978-0-8137-2376-1

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Xing, L., Wu, J., Lu, Y., Lu, J., and Ji, Q. (2009). "Aerodynamic characteristics of the crest with membrane attachment on Cretaceous pterodactyloid Nyctosaurus." Acta Geologica Sinica, 83(1): 25-32.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Carpenter, K. (2003). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale)." High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9053-0

- ↑ Marsh, O.C. (1876a). "Notice of a new sub-order of Pterosauria." American Journal of Science, 11(3): 507-509.

- ↑ Marsh, O.C. (1876b). "Principal characters of American pterodactyls." American Journal of Science, 12: 479-480.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Marsh, O.C. (1881). "Note on American pterodactyls." American Journal of Science, 21: 342-343.

- ↑ Price, Llewellyn Ivor (1953). "A presença de Pterosauria no Cretáceo Superior do Estado da Paraíba". Notas Preliminares e Estudos, Divisão de Geologia e Mineralogia, Brasil (71): 1–10.

- ↑ Kellner, Alexander Wilhelm Armin (1989). "Os répteis voadores do cretáceo brasileiro". Anuário do Instituto de Geociências 12: 86–106. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

External links

- Nyctosauridae (scroll down) in The Pterosaur Database