Nordic countries

| Nordic countries |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| Capitals | ||

| Languages | ||

| Membership | Countries / territories

|

|

| Area | ||

| - | Total | 3,501,721 km2 1,352,022 sq mi |

| Population | ||

| - | 2012 estimate | 25,650,540 |

| - | 2000 census | 25,478,559 |

| - | Density | 7.24/km2 18.8/sq mi |

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate | |

| - | Total | $1,049,8564136[??] million |

| - | Per capita | $41,205 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate | |

| - | Total | $1,621,658 million |

| - | Per capita | $63,647 |

| Currency | ||

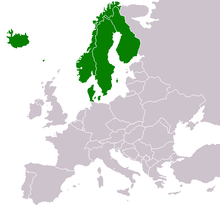

The Nordic countries make up a region in Northern Europe and the North Atlantic, consisting of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden as well as their associated territories, the Åland Islands, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Svalbard and Jan Mayen. In English, "Scandinavia" is sometimes used as a synonym for the Nordic countries (often excluding Greenland), but that term more properly refers only to Denmark, Norway and Sweden.[1]

The region's five nation-states and three autonomous regions share much common history as well as common traits in their respective societies, such as political systems and the Nordic model. Politically, Nordic countries do not form a separate entity, but they co-operate in the Nordic Council. The Nordic countries have a combined population of approximately 25 million spread over a land area of 3.5 million km² (Greenland accounts for around 60% of the total area).

Although the area is linguistically heterogeneous, with three unrelated language groups, the common linguistic heritage is one of the factors making up the Nordic identity. The North Germanic languages – Danish, Norwegian and Swedish – are considered mutually intelligible. These languages are taught in school throughout the Nordic countries; Swedish, for example, is a mandatory subject in Finnish schools, whereas Danish is mandatory in Icelandic, Faroese and Greenlandic schools. Besides these and the insular Scandinavian languages Faroese and Icelandic, all belonging to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European language group, there are the Finnic and Sami branches of the Uralic languages, spoken in Finland and in northern Norway, Sweden and Finland, respectively, and Greenlandic, an Eskimo–Aleut language, spoken in Greenland.

Etymology and terminology

The term "Nordic countries" is derived indirectly from the local term Norden (used in the North Germanic languages; Danish, Norwegian and Swedish), which literally means "The North(ern lands)".

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines "Nordic" as an adjective dated to 1898 with the meaning "of or relating to the Germanic peoples of northern Europe and especially of Scandinavia" or "of or relating to a group or physical type of the Caucasian race characterized by tall stature, long head, light skin and hair, and blue eyes".[2]

Use of Nordic countries vs. Scandinavia

In English usage, the term "Scandinavia" is sometimes used—though not consistently—as a synonym for the Nordic countries. From the 1850s, Scandinavia was considered to include, politically and culturally, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Geographically, the Scandinavian Peninsula includes mainland Sweden and mainland Norway. The Faroe Islands and Iceland are "Scandinavian" in the sense that they were settled by Scandinavians and speak Scandinavian languages, but geographically they are not part of Scandinavia. Having once been a part of Sweden, Finland has been significantly influenced by Swedish culture and part of it is geographically within Scandinavia, whereas the Finnish language is not related to the Scandinavian languages. Greenland was settled by the Norse, and is currently under Danish sovereignty, while geographically it is part of North America.

The "Nordic countries" is used unambiguously for Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland, including their associated territories (Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and the Åland Islands).[3] Scandinavia can thus be considered a subset of the Nordic countries. Furthermore, the term Fennoscandia refers to Scandinavia, Finland and Karelia, excluding Denmark and overseas territories; however, the usage of this term is restricted to geology, when speaking of the Fennoscandian Shield (Baltic Shield).

In addition to the mainland Scandinavian countries of:

-

Denmark (a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system)

Denmark (a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system) -

Norway (a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system, independent since 1905)

Norway (a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system, independent since 1905) -

Sweden (a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system)

Sweden (a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system)

...the Nordic countries also include:

-

Faroe Islands (an autonomous country within the Danish Realm, self-governed since 1948)

Faroe Islands (an autonomous country within the Danish Realm, self-governed since 1948) -

Finland (a parliamentary republic, independent since 1917)

Finland (a parliamentary republic, independent since 1917) -

Åland Islands (an autonomous province of Finland since 1920)

Åland Islands (an autonomous province of Finland since 1920) -

Greenland (an autonomous country within the Danish Realm, self-governed since 1979)

Greenland (an autonomous country within the Danish Realm, self-governed since 1979) -

Iceland (a parliamentary republic, independent since 1918, )

Iceland (a parliamentary republic, independent since 1918, )

Chronology

| Century | Nordic political entities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21st | Denmark (EU) | Iceland | Faroes | Greenland | Norway | Sweden (EU) | Åland (EU) | Finland (EU) | |

| 20th | Denmark | Sweden | Åland | Finland | |||||

| 19th | Denmark | United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway | Grand Duchy of Finland | ||||||

| 18th | Denmark–Norway | Sweden | |||||||

| 17th | |||||||||

| 16th | |||||||||

| 15th | Kalmar Union | ||||||||

| 14th | Denmark | Norway | Sweden | ||||||

| 13th | |||||||||

| 12th | Icelandic Free State | ||||||||

| Peoples | Danes | Icelanders¹ | Faroese¹ | Greenlanders | Norwegians | Swedes | Swedes | Finns | |

| Minorities | Germans | Danes | Norwegians/Danes | Sami/Kvens | Finns/Sami /Jamts² | Finns | Swedes/Sami/Karelians | ||

- Note: Italics indicate a dependent territory or autonomous area and italicised countries (e.g. Greenland and the Faroe Islands) are not sovereign states.

- 1: The original settlers of the Faroes and Iceland were of Nordic (mainly Norwegian) origin, with a considerable element of Celtic or Pictish origin (from Ireland and Scotland).

- 2: The settlers of Jämtland were of Norwegian — more specifically Trøndish — origin and their ancestors founded their own state similar to the Icelandic one governed by the Jamtamót assembly of free men.[citation needed]

Nordic Passport Union

The Nordic Passport Union, created in 1954, and implemented on May 1, 1958, allows citizens of the Nordic countries: Denmark (Faroe Islands included since January 1, 1966, Greenland not included), Sweden, Norway (Svalbard, Jan Mayen, Bouvet Island and Queen Maud's Land not included), Finland and Iceland (since September 24, 1965) to cross approved border districts without carrying and having their passport checked. Other citizens can also travel between the Nordic countries' borders without having their passport checked, but still have to carry some sort of approved travel identification documents.

Since 1996, these countries have been part of the larger EU directive Schengen Agreement area, comprising 30 countries in Europe. Border checkpoints have been removed within the Schengen zone and only a national ID card is required. Within the Nordic area any means of proving one's identity, e.g. a driving licence, is valid for Nordic citizens, because of the Nordic Passport Union.

Since March 25, 2001, the Schengen acquis has fully applied to the five countries of the Nordic Passport Union (except for the Faroe Islands). There are some areas in the Nordic Passport Union that give extra rights for Nordic citizens, not covered by Schengen, such as less paperwork if moving to a different Nordic country, and fewer requirements for naturalisation.

Political dimension and divisions

| EU | Eurozone | NATO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | Yes | No | Yes |

| Finland | Yes | Yes | No |

| Iceland | No | No | Yes |

| Norway | No | No | Yes |

| Sweden | Yes | No | No |

The Nordic region has a political dimension in the joint official bodies called the Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers. In this context, several aspects of the common market as in the European Union have been implemented decades before the EU implemented them. Intra-Nordic trade is not covered by the CISG, but by local law.

In the European Union, the Northern Dimension refers to external and cross-border policies covering the Nordic countries, the Baltic countries, and Russia.

The political cooperation between the Nordic Countries has not led to a common policy or an agreement on the countries' memberships in the European Union, Eurozone, and NATO. Norway and Iceland are only members of NATO, while Finland and Sweden are only members of the European Union. Denmark alone participates in both organizations. Only Finland is a member of the Eurozone. The tasks and policies of the European Union overlap with the Nordic council significantly, e.g. the Schengen Agreement partially supersedes the Nordic passport free zone and a common labor market.

Additionally, certain areas of Nordic countries have special relationships with the EU. For example, Finland's autonomous island province Åland is not a part of the EU VAT zone.

National symbols

All Nordic countries, including the autonomous territories of Faroe and Åland Islands, have a similar flag design, all based on the Dannebrog, the Danish flag. They display an off-center cross with the intersection closer to the hoist, the "Nordic cross". Greenland and the Sami people have adopted flags without the Nordic cross, but they both feature a circle which is placed off-center, similar to the cross.

Denmark

-

Flag of Denmark, "Dannebrog"

-

Mute Swan, the National Bird of Denmark

-

Ogier the Dane, H.P. Pedersen-Dan's statue of Holger Danske at Kronborg castle, Denmark

Faroe Islands

-

Flag of the Faroe Islands, "Merkið"

-

The Brinn, the National Bird of the Faroe Islands

-

Students wearing the National Costume of Faroe Islands

Greenland

-

Flag of Greenland, "Erfalasorput"

-

Polar bear, the National Animal of Greenland

-

Kangertittivaq,

Icebergs in Scoresby Sund, eastern Greenland - the longest fjord in the world

Finland

-

Flag of Finland, "Siniristilippu"

-

Brown bear, the National Animal of Finland

-

Finnish Maiden, "Suomen neito"

Åland Islands

-

.jpg)

Roe Deer, the National Animal of the Åland Islands

-

Reenactment of an 1800s farmer's wedding

Iceland

-

Gyrfalcon, the National Animal of Iceland

-

The Mountain Lady, Fjallkonan

Norway

-

Elk (Moose), the National Animal of Norway

-

National costumes of Norway

Sweden

-

Elk (Moose), the National Animal of Sweden

Sami people

-

Coat of arms of the Finnish region of Lapland

-

Man wearing traditional Sami costume

Geography

-

Satellite map of European part of the Nordic countries, except for Jan Mayen and Svalbard.

-

Saana fell in Northern Finland seen from the south.

-

The beach Grenen, Skagen in Denmark

-

Galdhøpiggen in Norway is the highest mountain in Nordic Countries.

-

The erupting Great Geysir in Haukadalur valley, Iceland, the oldest known geyser in the world.

-

The southernmost island of the Faroe Islands, Suðuroy.

-

Moskusokselandet in Northeast Greenland National Park, Greenland

-

Archipelago Sea in Finland and Åland is the largest archipelago in the world by the number of islands

-

Lake Päijänne is one of tens of thousands of lakes in Finnish Lakeland.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1800 | 5,161,000 | — |

| 1850 | 8,736,000 | +69.3% |

| 1900 | 12,306,000 | +40.9% |

| 1950 | 18,757,000 | +52.4% |

| 2000 | 24,116,000 | +28.6% |

Demographics

| Name of country, with flag | Population (2011) |

Source | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|

| |

9,540,065 | [4] | Stockholm |

| |

5,600,000 | [5] | Copenhagen |

| |

57,615 | [6] | Nuuk |

| |

49,267 | [7] | Tórshavn |

| |

5,426,090 | [8] | Helsinki |

| |

28,361 | [9] | Mariehamn |

| 5,050,133 | [10] | Oslo | |

| |

321,575 | [11] | Reykjavík |

| Total | 26,071,668 | [12] |

Countries with close relations to the Nordic countries

Several countries have a long and close relationship with and often identify with some or all of the Nordic countries. These are for the most part not regarded as part of the Nordic group themselves, although all except Germany and Poland are classified as Northern Europe in the United Nations geoscheme.

Estonia

Estonia has widely been thought of as geographically a Baltic state and a part of Northern Europe; Many Estonians consider themselves to be Nordic, as the term Balts or Baltic people does not apply to Estonians because of their descending from the Baltic Finns.[13] The term Baltic as a concept to group Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia has been criticized, as what the three nations have in common almost wholly derives from shared experiences of occupation, deportation, and oppression; what these countries do not share is a common culture or identity. Furthermore, the original use of the word Balt appears in the 19th century referring only to the Germans living in the region.[14]

With the rise of Christianity, centralized authority in Scandinavia and Germany eventually led to the Northern crusades. The northern part of Estonia was part of medieval Denmark during the 13th-14th centuries, being sold to the Teutonic Order after St. George's Night Uprising in 1346. The name of the Estonian capital, Tallinn, is thought to be derived from the Estonian taani linn, meaning 'Danish town' (see Flag of Denmark for details). Parts of Estonia were under Danish rule again in the 16th-17th centuries, before being transferred to Sweden in 1645.

Estonia was part of the Swedish Empire from 1561 until 1721, when it was ceded to Russia in the Treaty of Nystad, following the outcome of the Great Northern War. The Swedish era became colloquially known in Estonia as the "good old Swedish times". However, the local Baltic German upper classes had stronger political and cultural dominance in the country from the 12th to the early 20th century than the Swedes, Danes, or Russians. There were Finnish, Danish, and Swedish volunteer units in the Estonian War of Independence. There were Estonian volunteers in the Finnish Winter War, Continuation War and the Alta Battalion in Norway during World War II.[citation needed]

In 2011, being a member of EU, NATO, OSCE, OECD, and the Eurozone, Estonia has taken another step north from the Baltic states closer to the Northern European society.[citation needed] Swedish ambassador, Mr. Dag Hartelius's speech on the Estonian Independence day, February 24, 2009, where he considered Estonia "A Nordic Country" gathered a lot of attention in the country and was widely considered as a great compliment.

The Nordic cross has a long history in Estonia, dating back to 1219. The Nordic flag is originated from Estonia, where according to the Danish legend, it fell from the sky during the Battle of Lyndanisse. Because of the long Danish and Swedish rule in Estonia, the Nordic cross flags have been evident as county flags in many of Estonian counties since 1219.

-

.svg.png)

The coat of arms of Tallinn (small) and Harjumaa -

Flag of Estonia proposed in 1919.

Historically, large parts of Estonia's north-western coast and islands have been populated by an indigenous ethnically Swedish population, the Estonian Swedes. The majority of Estonia's Swedish population fled to Sweden in 1944, escaping the advancing Soviet Army. In 2007, Estonian Swedes were granted official cultural autonomy under Estonian law.[15] Since regaining independence in 1991, Estonia has expressed interest in joining the Nordic Council. In 2003, the foreign ministry hosted an exhibit called "Estonia: Nordic with a Twist."[16] In 2005, Estonia also joined the European Union's Nordic Battle Group.

Lithuania

Lithuania's relations with Nordic countries date back to ancient times. Early written sources mention battles between the Vikings, led by king Olof, and the Curonians in Apuolė village in A.D. 850. The oldest reference of Lithuanians is found in Eric's Chronicle, dated between about 1320 and 1335. It includes narration of Swedish Junker Karl, who due to his bad relations with Birger Jarl went into voluntary exile by joining the Teutonic Knights in Livonia and was later killed by Samogitians in 1260 at a Battle of Durbe. The ties between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Sweden intensified from 1562, when John III of Sweden married Katarina Jagellonica in the Cathedral of Vilnius and the Royal Palace of Lithuania. Sixteen years after this marriage the throne of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth passed to Sigismund III Vasa and later to his son Ladislaus IV Vasa. In 1648 John II Casimir Vasa became the Grand Duke of Lithuania and the King of Poland.

The next important step in the history of Lithuania-Sweden relations is the Kėdainiai Union, an agreement between several magnates of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the king of the Swedish Empire, Charles X Gustav. It was signed on 20 October 1655 during the "Swedish Deluge", part of the Second Northern War. In contrast the preceding Treaty of Kėdainiai of 17 August, which put Lithuania under Swedish protection, the purpose of the Swedish-Lithuanian union was to end Lithuania's union with Poland, and set up two separate principalities in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The agreement did not last for long and never came into effect, as the Swedish defeat in the Battles of Warka and Prostki as well as a popular uprising in both Poland and Lithuania put an end both to Swedish power and the influence of the Radziwiłłs.

The Great Northern War (1700–21) started when an alliance of Denmark–Norway, Saxony, Poland-Lithuania and Russia declared war on the Swedish Empire, launching a threefold attack at Swedish Holstein-Gottorp, Swedish Livonia, and Swedish Ingria, sensing an opportunity as Sweden was ruled by the young Karl XII, who was 18 years old and inexperienced at the time.

Despite the tense relations in the 18th century, Sweden was the first state to accord Lithuania de facto recognition on the 12th of December, 1918. On the 18th of December,1918, the Bureau of Lithuanian Press was opened, and on the 12th of January, 1919, the first Lithuanian Diplomatic Agency was established in Stockholm. Diplomatic relations between Lithuania and Norway were established on the 29th of July, 1921, when a diplomatic mission, led by Jonas Aukštuolis, was established.

During the Lithuania‘s occupation by the USSR, Stockholm became the centre of culture, politics and resistance. After the regain of independence and during the integration into the European and transatlantic structures, Nordic countries strongly supported by their Baltic neighbors. The Nordic-Baltic co-operation took place in various levels: networking and cooperation were established among politicians, civil servants and civil societies.

Currently, Nordic and Baltic cooperation takes place within various formats: European Union's Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region, NB8, NB6, E-PINE, Nordic Council, Baltic Assembly, Council of the Baltic Sea States, etc. The cooperation between Lithuania and Other Baltic and Nordic countries includes not only political and security topics – countries are bound together by business and economic matters too. Lithuanian banking system is mainly operated by the Scandinavian banks SEB, Nordea, Swedbank, and DnB. Nordic countries are also amongst the largest investors in Lithuania. In 2010 Denmark's share in total FDI in Lithuania was 10.4%, Sweden's 8.9%, Finland's 4.8%, Norway's 3.3% and Iceland's 0.5%. All together Nordic countries account for nearly 1/3 of all FDI in Lithuania (27.9%).

Nordic countries are also important Lithuania's trade partners all together accounting for 9.1% of all Lithuania's exports in 2011. The largest Nordic market for Lithuania's products and services is Sweden accounting for 3.6% of all Lithuania's exports. Denmark's share in Lithuania's exports is 2.1%, Norway's 2.0%, Finland's 1.3% and Iceland's 0.1%.

Also, Nordic countries are important in Lithuania's import structure – all together they account for 7.5% of all Lithuania's imports. Again, Sweden is the leader from all the Nordic countries with its 3.3% in all Lithuania's imports (Finland – 2.1%, Denmark – 1.6%, Norway – 0.4% and Iceland – 0.1%).

Nordic countries are a popular destination for Lithuanian emigrants – in 2011 more that 7% of all the Lithuania's people who declared emigration, chose Norway as their new country of residence. Immigrants from Norway account for 7.5% of all the immigration to Lithuania.

Latvia

Latvia has a long history of political, economic and cultural relations with the Nordic countries. During the Viking Age the indigenous tribes of present-day Latvia, the Latvian Vikings - the Couronians, Semigallians, Latgallians and Livs - both fought and traded with Scandinavian Vikings. The chief items of barter were bees-wax, furs, amber and silver. The Vikings travelled their so-called Eastern route, across the Baltic Sea, along the Daugava and Dnieper rivers and across the Black Sea towards Constantinople.[17] The seafaring Couronians ("Latvian Vikings") from Courland and the Oeselians ("Estonian Vikings") from Saaremaa battled the Scandinavian Vikings and raided their lands.[18] In 1187 they pillaged and sacked Sigtuna, by that time Sweden's largest and richest city.[19] People in Denmark prayed: "save us Our God from the Couronian pirates".[20][21] The Couronians participated in the Battle of Bråvalla on Swedish side against the Danes.[22] Courland (or Kurland) and the Couronians (or Kurs) are mentioned in the Old Norse sagas, such as the Heimskringla[23] and Egill Skallagrímsson's saga.[24] Seeburg (now Grobiņa near Liepāja) was a Scandinavian settlement in Courland.[18][25] Weapons, ornaments and large cemeteries of mixed Baltic and Viking character prove Swedes and Gotlanders were dwelling among the native population.[26] Boats of the Couronians and Vikings were similar in construction and decoration.[17] It is thought that in this age loanwords were adopted, like lord or king: in Swedish kung or konung, Latvian kungs and Danish konge .[18]

The Northern Crusades, undertaken by the kings of Denmark and Sweden and German Livonian and Teutonic military orders, brought Christianity to the pagan tribes of Latvia. The Reformation brought Protestant Lutheranism. Between 1560-1585 the Bishopric of Courland belonged to king Frederick II of Denmark, his brother Magnus of Holstein lived and died at Piltene. Between 1561-1721 the Duchy of Livonia, which constituted the southern part of modern Estonia and northern part of modern Latvia, became Swedish Livonia, a dominion of the Swedish Empire. These times became known as "the good Swedish period",[27] although the local Baltic German upper class kept their strong political, economic and cultural dominance over the peasant people. Alongside Finns and Estonians, Latvians fought with the Swedes in the Thirty Years' War against the Holy Roman Empire. Livonia, Sweden and Gothland were part of the same Hanseatic League trading chamber, with first Visby and later Riga as its chief city. Duke Jacob (1642-1682) of Courland leased iron and copper mines in Norway to support ship building and global seafaring.[28] The flags of Ventspils, Cēsis and Alūksne bear a Nordic cross. Like other Northern Europeans the Latvians celebrate Midsummer solistice and St. Johns Day.

An ethnic-linguistic minority of Latvia are the Finnic Livs. The Liv people are indigenous inhabitants of present-day Latvia and ancient Livonia. The extinct[29] Liv language is a Baltic-Finnic language related to Estonian, Finnish, Karelian, Veps and Votic. Researchers believe about 15,000-28,000 Livs to have lived in the 12th century.[30] In 2011 there were 180 registered Livs in Latvia.[31] and about 30 native speakers in the world.[32] The Livonian Coast (Livonian: Līvõd Rānda) in Northern Courland is a protected area encompassing twelve Livonian villages. The Liv Peoples House (Livonian: Līvõd Rovkuodā) is located in the Livonian village of Mazirbe Livonian: Irē) and the Liv Culture Center (Livonian: Līvõ Kultūr Sidām) in Riga.[33] Livonian is taught in universities in Latvia, Estonia and Finland.

Since the early 1990s Latvia takes part in Nordic-Baltic cooperation (NB8: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Sweden),[34] for which former Latvian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Valdis Birkavs and former Danish Minister of Defence Søren Gade wrote the 2010 NB8 Wise Men Report.[35] The NB6 (Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia) is a framework for meetings on EU related issues. On August 30, 2011 the Nordic and Baltic countries signed an agreement on diplomatic cooperation.[36][37][38] Latvia also cooperates with the Nordic countries within the Council of the Baltic Sea States and the European Union's Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region. The Nordic Council has an office in Riga and Latvia is a member of the Nordic Investment Bank. The Nordic countries are among the most important trading partners of Latvia.

| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1919—1940 1991–present | Naval ensign | |

| ?—present | Rear Admiral’s Flag | |

| ?—present | Border guard |

Poland

The King of Denmark, Norway and Sweden Erik of Pomerania ruled the Kalmar Union countries during the period of 1396 to 1442. His real name was Bogislav though, and he was son of Duke Vratislav VII of the Slavonic dynasty of Gryf. King Erik's native language was Polish.

By the marriage of the Swedish king Johan III (1537-1592, king from 1568) and Polish princess Catherine Jagellon their son, Sigismund III of Poland and Sigismund of Sweden (without number in Swedish history) became sovereign of both kingdoms. Due to the reformation, which had been adapted in Sweden by Sigismund's grandfather, Gustav Wasa, problems with the catholic Sigismund soon arrived and ended with that Sigismund was thrown aside by his uncle Karl IX of Sweden in Sweden.

Eastern parts of former Swedish Pomerania, including the Capital city of the area, Stettin (today known as Szczecin), became in 1945 Polish.

Both Sweden and Denmark have several ferry lines that cross the Baltic Sea. These include Świnoujście - Ystad, Świnoujście - Copenhagen, Świnoujście - Bornholm, and Gdańsk - Karlskrona. Polish labour is in high demand especially in the southern parts of Sweden and in Denmark. Most of the Polish workers are employed in construction, carpentry, painting and landscaping, but academic collaboration and employment at university level is not uncommon.

Some medical services are notably cheaper in Poland than in Denmark and Sweden, including plastic surgery and dental care. Polish dentists in combination with ferry lines and Polish tourist offices of Szczecin and Gdańsk often advertise their lower fares in the Nordic countries in order to encourage visits. Cross border-shopping combined with weekend travels is also popular. Alcohol and cigarettes, as well as a lot of building materials, construction products (like windows etc.) and other tradable goods are cheaper in Poland.

United Kingdom

England

The Kingdom of England was mostly founded by the invading Angles, Jutes (from the Jutland Peninsula) and Saxons from what is now southern Denmark and Northern Germany. The name of England means 'land of the Angles', and the use of this term can be traced back to Bede in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum.

Despite this however the Viking Age had a very important impact on the demographic makeup of modern-day England. In addition to the Migration Period, much of England, particularly East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria and York (known as "Jorvik"),[39] were once part of the Danelaw, an area of England ruled by the Scandinavian Vikings.

In contrast to England, the Norwegian Vikings tended to raid, rather than settle what is now Scotland, Wales and Ireland. In the 11th century, Danish King Cnut the Great inherited the Kingdom of England, which was then the most prosperous monarchy in Europe, becoming king of England, Denmark, Norway and part of Sweden. This monarchy became known as the "North Sea Empire".[40]Scotland

During the Viking Age, Scotland was frequently attacked from Norway, giving rise to a culture of Norse-Gaels, similar to the Anglo-Dane culture of Northern England. Many Scottish clans are Norse-Gaelic in origin, including the Macdonalds. Areas such as Caithness, Sutherland and the Hebrides were under Norse rule for long periods.

In the Middle Ages under David I, many people arrived in the newly founded burghs from other European countries including Scandinavia. During the Middle Ages and Early Modern Era, Scotland traded extensively with the lands along the Baltic, including Scandinavia and the Baltic. Some of these people emigrated to the places where they were trading.[41]

Nowadays, many Scottish National Party members and supporters of Scottish independence see the Nordic countries as strong allies and see the Nordic model as something which should be implemented in Scotland.[42][43][44] The Icelandic Prime Minister, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson stated that in the event of a yes vote in the 2014 referendum, the other Nordic nations could allow Scotland to become a member of the Nordic Council.[45][46] In recent years, Nordic conferences on the environment have also included delegates from Scotland.[47]

Shetland and Orkney

The Northern Isles of Scotland—Orkney and Shetland—have a long-established Nordic identity. The islands were ruled from Norway and later also Denmark for more than 500 years, but ownership defaulted to the crown of Scotland in 1472 following non-payment of the marriage dowry of Margaret of Denmark and Norway, queen of James III of Scotland.

The impact of centuries of Scandinavian rule and migration has led to an arguably distinct culture and identity within Orkney and Shetland, that has survived even after 500 years since the transfer of the islands to Scotland. For example, almost every place name in use can be traced back to the Vikings.[48] The Norn language was a form of Old Norse, which continued to be spoken until the 18th century when it was replaced by an insular dialect of Scots known as Shetlandic.[49]

Another form this culture manifests itself in is the Up Helly Aa festival in Shetland. This festival is one of a variety of fire festivals of Scandinavian origin held annually in the middle of winter. The festival in its present, highly organised form is just over 100 years old. Originally, a festival held to break up the long nights of winter and mark the end of Yule, the festival has become one celebrating the isles' heritage and includes a procession of men dressed as Vikings and the burning of a replica longship.[50]

In later years financial relations, particularly in the maritime industries, have been important. Cultural and sporting exchanges are frequent. A genetic survey showed that over 60% of the male population of Shetland and Orkney had Western Norwegian genes.[citation needed]

These links to Scandinavia are reflected in the islands' flags, both of which are based around a Nordic cross:

|

|

| Orkney | Shetland |

In the context of the Scottish independence debate, a number of Islanders have discussed the possibility of becoming independent of Scotland.[51][52] Citing similar arguments to the Yes Campaign, such as Oil wealth vs population size, and arguably significant cultural differences from the rest of Scotland, this particular viewpoint is growing amongst the population of Shetland and Orkney.[53]

Ireland

Ireland had a long history with the Norse. Viking raids from Norway commonly struck the island. Eventually, the Norse came to settle, and many of Ireland's towns, including Dublin, Waterford, Wexford, and Limerick, were originally Viking settlements, and at the Battle of Clontarf, Gaels and Norse fought on both sides, and intermarriage between the two groups by this time was routine. As in Scotland, the Norse assimilated into the larger population, many Irish surnames of Norse origin. Ireland was also invaded and settled by Normans, who were Norse who had adopted the French language in Normandy.

Genetically, the Irish, Germans and Scandinavians are closely related. According to recent genetic analysis, both mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms showed a noticeable genetic affinity between the Irish, Swedes, Germans and Norwegians. These factors lead to a significant number of Irish people being included in the Nordic race.

Ireland is a member of the EU's Nordic Battle Group.

Germany

Before the Industrial Revolution, the Low German-speaking peoples of northern Germany were a part of the seafaring culture of Scandinavia, rather than the more land-based lifestyle in the rest of Germany. Even today, the folk tales of northern Germany have a unique focus on the sea and sailing. Low German itself is a North Sea Germanic language, giving it the same origin as English, and a closer cultural position to Scandinavia than the continental Germanic lands.

Parts of the states in northern Germany, namely Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg were at times part of Denmark and Lower Saxony, Bremen and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern part of Sweden, and have a long history of cooperation dating back to the medieval Hanseatic League. In the 15th century, Stockholm had a German majority population, and Germans paid more than half of the city's taxes.

Southern Schleswig on the Jutland peninsula was conquered and reconquered both by the Germans and the Danes, i.e. the border between Denmark and Germany changed several times over the centuries. Particularly the northern parts of present Schleswig-Holstein have a significant ethnic Danish minority. The region had a Scandinavian identity in Hedeby and Angeln up until its transfer to Germany in the mid 19th century and its subsequent Germanisation. Today, the Nordic character of Southern Schleswig's society and its inhabitants is still very prominent. There are Danish state schools in the area, and the Danish minority is active both politically and culturally.

Likewise there is also a German community in South Jutland.

Swedish Pomerania was once part of the Swedish kingdom; a time when the local University of Greifswald, at that time Sweden's oldest university, attracted both students and professors from Sweden. The cultural heritage survives in the form of many buildings, though the Swedish population either left the region when the Swedish Empire declined or was assimilated into mainstream German society.

Genetically, Germans and Scandinavians are also closely related. According to recent genetic analysis, both mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms showed a noticeable genetic affinity between Swedes and Germans (conclusions also valid for Norwegians).[54]

See also

- Baltoscandia

- Climate of the Nordic countries

- Nordic Council / Northern Dimension

- Nordic Cross

- Scandinavia / Northern Europe / Baltic region

- Subdivisions of the Nordic countries

References

- ↑ "Scandinavia". In Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. Retrieved 10 January 2008: "Scandinavia: Denmark, Norway, Sweden—sometimes also considered to include Iceland, the Faeroe Islands, & Finland." (Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines "Nordic" as an adjective dated to 1898 with the meaning "of or relating to the Germanic peoples of northern Europe and especially of Scandinavia."), "Scandinavia" (2005). The New Oxford American Dictionary, Second Edition. Ed. Erin McKean. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-517077-6: "a cultural region consisting of the countries of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark and sometimes also of Iceland, Finland, and the Faroe Islands"; Scandinavia (2001). The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Retrieved January 31, 2007: "Scandinavia, region of N Europe. It consists of the kingdoms of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark; Finland and Iceland are usually considered part of Scandinavia"; Scandinavia. (2007). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 31, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: "Scandinavia, historically , part of northern Europe, generally held to consist of the two countries of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Norway and Sweden, with the addition of Denmark"; and Scandinavia. (2006). Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 30, 2007: "Scandinavia (ancient Scandia), name applied collectively to three countries of northern Europe—Norway and Sweden (which together form the Scandinavian Peninsula), and Denmark". Archived 2009-11-01.

- ↑ Nordic. Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ↑ Saetre, Elvind (2007-10-01). "About Nordic co-operation". Nordic Council of Ministers & Nordic Council. Retrieved 2008-01-09. "The Nordic countries consist of Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Finland, the Åland Islands, Iceland, Norway and Sweden."

- ↑ "Befolkningsstatistik". Statistiska centralbyrån. 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ "Quarterly Population (ultimo)". Statistics Denmark. 2011-02-09. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ "Greenland". Statistics Greenland. 2011-01-01. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ "Statistics Faroe Islands". Statistics Faroe Islands. 2011-04-01. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ "The current population of Finland". Statistics Finland. 2011-03-31. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ "ÅSUB". ÅSUB. 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ "Population". Statistics Norway. 2011-04-01. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ "Statistics Iceland". Government. The National Statistical Institute of Iceland. 2011-01-01. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ This number was derived by adding up the referenced populations (from the provided table) of Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Iceland, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Åland.

- ↑ "Estonian Life"

- ↑ Ilves, Toomas Hendrik. "Estonia as a Nordic Country" to the Swedish Institute for International Affairs – December 14, 1999.

- ↑ "Estonian Swedes Embrace Autonomy Rights" Citypaper, 2007

- ↑ "Estonia – Nordic with a Twist". Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs, 2004 (last updated).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Latvia in Brief". Latvian Institute. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Ģērmanis, Uldis (2007). The Latvian Saga. Atēna. p. 41. ISBN 978-9984-34-291-7.

- ↑ Ģērmanis, Uldis (2007). The Latvian Saga. Atēna. p. 44. ISBN 978-9984-34-291-7.

- ↑ Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to the past: a cultural history of the Baltic people. Central European University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-963-9116-42-9.

- ↑ Ģērmanis, Uldis (2007). The Latvian Saga. Atēna. p. 43. ISBN 978-9984-34-291-7.

- ↑ Ģērmanis, Uldis (2007). The Latvian Saga. Atēna. p. 42. ISBN 978-9984-34-291-7.

- ↑ "Heimskringla - Online collection of Old Norse source material". Heimskringla.no - Old Norse Prose and Poetry. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ Hallvard, Lie; Snorri Sturluson. Egil's Saga. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Logan, F. Donald (2005). The Vikings in History (Third Edition). Hutchinson & Co (Publishers) Ltd. p. 164. ISBN 0-415-32756-3.

- ↑ Kendrick, T. D. (2004). A history of the Vikings. Dover Publications. p. 189. ISBN 0-486-43396-X.

- ↑ Ģērmanis, Uldis (2007). The Latvian Saga. Atēna. p. 126. ISBN 978-9984-34-291-7.

- ↑ Ģērmanis, Uldis (2007). The Latvian Saga. Atēna. p. 132. ISBN 978-9984-34-291-7.

- ↑ "Death of a language: last ever speaker of Livonian passes away aged 103". June 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Livonia Maritima Project - History of Livonia". Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības (Latvian)". Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ Ernštreits, Valts. "The Liv language today". Livones.lv - Liv culture and language portal. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Livones.lv - Liv culture and language portal". Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Nordic-Baltic co-operation". Nordic Council. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Cooperation of Baltic and Nordic States". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Latvia. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Reinforced diplomatic cooperation between the Nordic and Baltic countries". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Norway - Regjeringen.no. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Reinforced diplomatic cooperation between the Nordic and Baltic countries". Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Sweden - Regeringen.se. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Nordics, Baltics Agree on Exchanging Diplomats". Estonian Public Broadcasting. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "York's history". City of York Council. 20 December 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- ↑ Laurence Marcellus Larson, Canute the Great: 995 (circ.)-1035 and the Rise of Danish Imperialism During the Viking Age, New York: Putnam, 1912, OCLC 223097613, p. 257.

- ↑ Haggett, Peter (2001-07-01). Encyclopedia of World Geography: The Nordic Countries. ISBN 9780761472896.

- ↑ Keating, Michael (2007). Scottish social democracy: progressive ideas for public policy. ISBN 9789052010663.

- ↑ McCall Smith, Alexander (1978). Power & manoeuvrability. ISBN 9780905470047.

- ↑ Mercer, John (1978). Scotland: the devolution of power. ISBN 9780714536279.

- ↑ National Collective. "Icelandic Prime Minister Ready to Welcome an Independent Scotland". Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ National Collective. "Scottish EU Membership Straightforward and in Denmark’s Interest". Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Heritage, Scottish Natural; Studies; Scottish Natural Heritage,Centre for Mountain Studies (2005-10-03). Mountains of Northern Europe: conservation, management, people and nature. ISBN 9780114973193.

- ↑ Julian Richards, Vikingblod, page 236, Hermon Forlag, ISBN 82-3020-016-5

- ↑ "Velkomen!" nornlanguage.com. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ "Up Helly Aa" Visit.Shetland.org. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ "Freedom for Shetland" blogs.spectator.co.uk Retrieved 31 February 2012.

- ↑ "Scottish Islands Home Rule" theguardian.com Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "Orkney Islands see Scottish referendum as chance of freedom " www.ft.com Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ http://hpgl.stanford.edu/publications/EJHG_2002_v10_521-529.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Nordic region. |

- Norden, website of the Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Nordregio, European centre for research, education and documentation on spatial development, established by the Nordic Council of Ministers. Includes maps and graphs.

- Go Scandinavia, official website of the Scandinavian Tourist Boards in North America.

- Scandinavia House, the Nordic Center in New York, run by the American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- vifanord, a digital library that provides scientific information on the Nordic and Baltic countries as well as the Baltic region as a whole.

- Mid Nordic Committee, Nordic organization to promote sustainable development and growth in the region.

- The Helsinki Treaty of 1962 Nicknamed as constitution of the The Nordic Countries.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Coordinates: 64°00′N 10°00′E / 64.000°N 10.000°E