Nodal precession

Nodal precession is the precession of an orbital plane around the rotation axis of an astronomical body such as the Earth. This precession is due to the non-spherical nature of a spinning body, which creates a non-uniform gravitational field.

Around a spherical body, an orbital plane would remain fixed in space around the central body. However, most bodies rotate, which causes an equatorial bulge. This bulge creates a gravitational effect that causes orbits to precess around the rotational axis of the central body.

The direction of precession is opposite the direction of revolution. For a typical prograde (in the direction of central body rotation) satellite orbit in an about the Earth, the longitude of the ascending node decreases, i.e. node precesses westward. If the orbit is retrograde, this increases the longitude of the ascending node i.e. node precesses eastward. This nodal progression enables sun-synchronous orbits to maintain approximately constant angle relative to the Sun.

Description

A non-rotating body of planetary scale or larger would be pulled by gravity into a sphere. Virtually all bodies rotate, however. The centrifugal force deforms the body so that it has an equatorial bulge. Because of the bulge the gravitational force on the satellite is not directly toward the center of the central body, but is offset toward the equator. Whichever hemisphere the satellite is in it is preferentially pulled slightly toward the equator. This creates a torque on the orbit. This torque does not reduce the inclination; rather, it causes a torque-induced gyroscopic precession, which causes the orbital nodes to drift with time.

Equation

The rate of precession depends on the inclination of the orbital plane to the equatorial plane, as well as the orbital eccentricity.

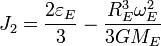

For a satellite in a prograde orbit about the Earth, the precession is westward (nodal regression), the node and satellite move in opposite directions.[1] A good approximation of the precession rate is

where

is the precession rate (rad/s)

is the precession rate (rad/s) is the body's equatorial radius (6 378 137 m for Earth)

is the body's equatorial radius (6 378 137 m for Earth) is the semi-major axis of the satellite orbit

is the semi-major axis of the satellite orbit is the eccentricity of the satellite orbit

is the eccentricity of the satellite orbit is its angular frequency of the satellite's motion (

is its angular frequency of the satellite's motion ( radians divided by its period)

radians divided by its period) its inclination

its inclination is the body's second dynamic form factor (

is the body's second dynamic form factor ( for Earth.)

for Earth.)

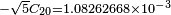

This last quantity is related to the oblateness as follows:

where

is the central body's oblateness

is the central body's oblateness is central body's equatorial radius

is central body's equatorial radius is the central body's rotation rate (7.292115×10−5 rad/s for Earth)

is the central body's rotation rate (7.292115×10−5 rad/s for Earth) is the product of the universal constant of gravitation and the central body's mass (3.986004418×1014 m3/s2 for Earth.)

is the product of the universal constant of gravitation and the central body's mass (3.986004418×1014 m3/s2 for Earth.)

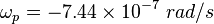

The nodal progression of low earth orbits is typically a few degrees per day to the west (negative). For a satellite in a circular 800 km altitude orbit at 56° inclination about the earth

The orbital period is 6052.4 s, so the angular velocity is 0.001038 rad/s. The precession is therefore

This is equivalent to -3.683 degrees/day, so the orbit plane will make one complete turn (in inertial space) in 98 days.

The apparent motion of the sun is approximately +1° per day (360° per year / 365.2422 days per tropical year ≈ 0.9856473° per day), so apparent motion of the sun relative to the orbit plane is about 2.8° per day, resulting in a complete cycle in about 127 days. For retrograde orbits  is negative, so the precession becomes positive. (Alternatively,

is negative, so the precession becomes positive. (Alternatively,  can be thought of as positive but the inclination is greater than 90°, so the cosine of the inclination is negative.) In this case it is possible to make the precession approximately match the apparent motion of the sun, resulting in a sun-synchronous orbit.

can be thought of as positive but the inclination is greater than 90°, so the cosine of the inclination is negative.) In this case it is possible to make the precession approximately match the apparent motion of the sun, resulting in a sun-synchronous orbit.

See also

- Axial precession or precession of the equinoxes in astronomy (same kind)

- Apsidal precession, the other kind of precession (argument of periapsis change)

References

- ↑ Brown, Charles. Elements of spacecraft design. p. 106.