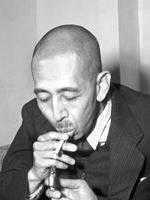

Nobusuke Kishi

| Nobusuke Kishi 岸 信介 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 31 January 1957 – 19 July 1960 Acting until 25 February 1957 | |

| Monarch | Shōwa |

| Preceded by | Tanzan Ishibashi |

| Succeeded by | Hayato Ikeda |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 November 1896 Tabuse, Japan |

| Died | 7 August 1987 (aged 90) |

| Political party | Liberal Democratic Party (1955–1987) |

| Other political affiliations |

Imperial Rule Assistance Association (1941-1945) Democratic Party (1952–1955) |

| Alma mater | Tokyo Imperial University |

| Signature |  |

Nobusuke Kishi (岸 信介 Kishi Nobusuke, 13 November 1896 – 7 August 1987) was a Japanese politician and the 56th and 57th Prime Minister of Japan from 25 February 1957 to 12 June 1958, and from then to 19 July 1960. Kishi was called Shōwa no yōkai (昭和の妖怪 or "the Shōwa era monster/devil").

Early life

Kishi was born Nobusuke Satō in Tabuse, Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi Prefecture, but left his family at a young age to move in with the more affluent Kishi family, adopting their family name. His biological younger brother, Eisaku Satō, would also go on to become a prime minister.

Early political career and WWII

Kishi attended Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) and entered the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in 1920. In 1935, he became one of the top officials involved in the industrial development of Manchukuo, where he was later accused of exploiting Chinese forced labor.[1] Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō, himself a veteran of the Manchurian campaign, appointed Kishi Minister of Munitions [2] in 1941, and he held this position until Japan's surrender in 1945. He was also elected to the Lower House of the Diet of Japan in 1942.

As with other members of the former Japanese government, Kishi was held at Sugamo Prison as a "Class A" war crimes suspect by the order of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers. Unlike Tōjō (and several other cabinet members), however, Kishi was released in 1948 and was never indicted or tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. However, he remained legally prohibited from entering public affairs because of the Allied occupation's purge of members of the old regime.

Post-WWII political career

When the purge was fully rescinded in 1952 with the end of the Allied occupation of Japan, Kishi was central in creating the "Japan Reconstruction Federation" (Nippon Saiken Renmei). He built his federation party around a number of former Minseito (one of the two main prewar conservative parties) politicians and control bureaucrats, and made Shigemitsu Mamoru, the former Foreign Minister, its nominal leader. The party goals were anti-communism, promotion of small and medium-sized businesses, deepening of U.S.-Japan economic relations, and revision of the Constitution. Kishi's federation failed in its first (and only) electoral test. When Yoshida Shigeru called for elections in the autumn of 1952, Kishi was not prepared and his young party was crushed at the polls.

Kisi flirted with joining the Japan Socialist Party but, at the urging of his brother, Sato Eisaku, he turned reluctantly to Yoshida's Liberal Party. Kishi rationalized cooperation with Yoshida as a way of getting inside the main conservative tent so that he might transform it from within. At first, Yoshida—whose battles with Kishi dated from their opposing positions during the wartime mobilization—wanted no part of him, so much so that he had intervened with the Occupation authorities to keep Kishi from being de-purged. But this was a time of fluid ideological borders and great political desperation. Kishi brought to the table considerable political resources. He had money and (not unrelatedly) a battalion of politicians, both of which made his partnership palatable, if not appealing, to Yoshida. In the event, Yoshida took him in and Kishi won his first postwar Diet seat in 1953, and was reelected eight times until his retirement from politics in 1979.

In 1955, the Democratic Party and Liberal Party merged to elect Ichirō Hatoyama as the head of the new Liberal Democratic Party. Two prime ministers later, in 1957, Kishi was voted in following the resignation of the ailing Tanzan Ishibashi.

In the first year of Kishi's term, Japan joined the United Nations Security Council, paid reparations to Indonesia, set up a new commercial treaty with Australia, and signed peace treaties with Czechoslovakia and Poland. In 1959, he visited Buenos Aires, Argentina. Kishi's next foreign policy initiative was much more difficult: reworking Japan's security relationship with the United States.

That November, Kishi laid down his proposals for a revamped extension of the US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty. After closing the discussion and vote without the opposition group in the Diet of Japan, demonstrators clashed with police in Nagatachō, at the steps of the National Diet Building. About 500 people were injured in the first month of demonstrations. Despite their magnitude, Kishi did not think much of the demonstrations, referring to them as "distasteful" and "insignificant." [3] Once the protests died down, Kishi went to Washington, and in January 1960 returned to Japan with a new and unpopular Treaty of Mutual Cooperation. Demonstrations, strikes and clashes continued as the government pressed for ratification of the treaty.

On June 10, White House Press Secretary James Hagerty arrived in preparation for a state visit of President Dwight Eisenhower. He was met at the airport by Ambassador Douglas MacArthur II. Knowing that leftist demonstrators lined the road from the airport they chose to travel by car rather than helicopter. They felt that if the demonstrators were going to resort to violence it would be better for both the US and Japanese governments to know rather than waiting to test their resolve at the arrival of the President. They also believed that if any violence ensued it would bias the Japanese populace against the demonstrators. As they approached the exit to the airport grounds a mob spearheaded by Zengakuren students closed in stoning the car, shattering windows, slashing tires, and trying to overturn them. Police reached them after 15 minutes and managed to clear a landing zone for a helicopter which transported them the rest of the way.[4] To his embarrassment, Kishi had to request the postponement of Eisenhower's state visit. The end of Eisenhower's term of office prevented it from being rescheduled.

The loss of face this entailed, along with his apparent inability to restrain the demonstrations resulted in factional disputes within the Liberal Democratic Party. On 15 July 1960 Kishi resigned and Hayato Ikeda became prime minister.

On 14 December 2006, Manmohan Singh, the Prime Minister of India, made a speech in the Diet of Japan. He stated "It was Prime Minister Kishi who was instrumental in India being the first recipient of Japan's ODA. Today India is the largest recipient of Japanese ODA and we are extremely grateful to the government and people of Japan for this valuable assistance."[5]

Controversies

Kishi illustrates the ambivalent role of America in post-war Japan,[6] and the difficulty of eradicating revisionism from a Japan where tainted political dynasties still clung to power. As a Prime Minister, Kishi's own heritage was ambivalent: on one hand he worked for international peace, but on the other he promoted revisionism by liberating war criminals and dedicating in Mount Sangane a headstone to Tojo and six other war criminals executed after the Tokyo trial, marking their grave as that of "the seven patriots who died for their country".[7]

Kishi's role in the late 1950s was to consolidate the conservative camp against perceived threats from the Japan Socialist Party. He is credited with being a key player in the initiation of the "1955 System": the extended period during which the LDP was the overwhelmingly dominant political party in Japan. His actions have been described as originating the most successful money-laundering operation in the history of Japanese politics.[8]

Honours

From the corresponding article in the Japanese Wikipedia

- Coronation Medal (November 1928)

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 5th Class (April 1934)

- Military Medal of Honour (April 1934)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (29 April 1967)

- United Nations Peace Medal (with Ryoichi Sasakawa) (1979)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (7 August 1987; posthumous)

Order of precedence

- Senior second rank (August 1987; posthumous)

- Senior third rank (July 1960)

- Senior fifth rank (September 1934)

- Fifth rank (September 1929)

- Senior sixth rank (September 1927)

- Sixth rank (August 1925)

- Senior seventh rank (October 1923)

Descendants

Shintarō Abe is Kishi's son-in-law, and his child Shinzō Abe, the current prime minister of Japan, is Kishi's grandson.

References

- ↑ Dower, John (2000). Embracing Defeat. W. W. Norton and Company. p. 454.

- ↑ Buruma, Ian. Year Zero: A History of 1945 (p. 187). Penguin Group US. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Bonus to be wisely spent, Time, 25 January 1960.

- ↑ Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960 Volume XVIII, Japan; Korea, Document 173

- ↑ Embassy of India in Japan; Prime Minister's speech to the Japanese diet on 14 December 2006 (Doc file)

- ↑ "America's Favorite War Criminal: Kishi Nobusuke and the Transformation of U.S.-Japan Relations" Michael Schaller

- ↑ " Far from Yasukuni, cemetery honors criminals" - Korea JoongAng Daily (15 août 2013)

- ↑ Kishi and Corruption: An Anatomy of the 1955 System, Japan Policy Research Institute Working Paper No. 83, December 2001.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Tanzan Ishibashi |

Prime Minister of Japan Jan 1957 – Jul 1960 |

Succeeded by Hayato Ikeda |

| Preceded by Mamoru Shigemitsu |

Minister of Foreign Affairs Dec 1956 – Jul 1957 |

Succeeded by Aiichiro Fujiyama |

| Preceded by Seizō Sakonji |

Minister of Commerce & Industry Oct 1941 – Oct 1943 |

Succeeded by Hideki Tōjō |

| |||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|