Noah

| Noah | |

|---|---|

Noah's Sacrifice by Daniel Maclise | |

| Constructor of the Ark | |

| Honored in |

Judaism Christianity Islam Mandaeism Baha'i Faith |

In Abrahamic religions, Noah (/ˈnoʊ.ə/[1]) or Noé or Noach, (Hebrew: נֹחַ, נוֹחַ, Modern Noaẖ Tiberian Nōăḥ; Syriac: ܢܘܚ Nukh; Arabic: نُوح Nūḥ; Ancient Greek: Νῶε) was the tenth and last of the pre-flood Patriarchs. The story of Noah's Ark is told in the Genesis flood narrative, and also told in Sura 71 of the Quran. The biblical account is followed by the story of the Curse of Ham. Besides the book of Genesis, Noah is also mentioned in 1st Chronicles, Isaiah, Ezekiel, the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, the book of Hebrews and the 1st and 2nd Epistles of Peter. He was the subject of much elaboration in later Abrahamic traditions, including the Qur'an.

Biblical account

Genesis

Noah was the tenth of the pre-flood (antediluvian) Patriarchs. His father Lamech "called his name Noah, saying, This [same] shall comfort us concerning our work and toil of our hands, because of the ground which the LORD hath cursed."[2] When Noah was five hundred years old, he begat Shem, Ham and Japheth (Genesis 5:32).

Genesis chapter six speaks of the conditions before the flood, that led to the decision by the LORD to destroy the earth – but there is a delay – for "Noah found grace in the eyes of the LORD." (6:1-8) A new section, "the generations of Noah", is begun in verse 9, and a repeat mention of the birth of Shem, Ham and Japheth appears in verse 10, providing a fixed time reference for the chronology of the chapter. (6:9-10) After these things, Noah was instructed by God to "make an ark", and fill it with two of every sort of living thing, and gather "all food that is eaten" for provisions for them all. (Genesis 6:11-22) The chapter ends with Noah's ark loaded with two of every sort, and fully provisioned, "according to all that God commanded him".

Genesis chapters seven and eight detail events related to the Genesis flood narrative.

After the Flood, Noah offered a sacrifice to God, who promised never again to destroy all life on Earth by a flood (Genesis 9:11) and gave the rainbow, called "my bow", as the sign of a covenant "between me and you and every living creature that [is] with you, for perpetual generations", (9:12-17) called the Noahic covenant. After this, Noah became a husbandman and he planted a vineyard: and he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and was uncovered within his tent. Noah's son Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father and told his brethren, which led to Ham's son Canaan being cursed by Noah.[3]

Noah died 350 years after the Flood, at the age of 950,[4] the last of the extremely long-lived antediluvian Patriarchs. The maximum human lifespan, as depicted by the Bible, diminishes rapidly thereafter, from almost 1,000 years to the 120 years of Moses.

Enoch

In 10:1-3 of the Book of Enoch, Uriel was dispatched by "the Most High" to inform Noah of the approaching "deluge".[5]

Origins

The Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, composed about 2500 BC, contains a flood story almost exactly the same as the Noah story in the Pentateuch, with a few variations such as the number of days of the deluge, the order of the birds, and the name of the mountain on which the ark rests. Andrew R. George submits that the flood story in Genesis 6–8 matches the Gilgamesh flood myth so closely, "few doubt" that it derives from a Mesopotamian account.[6] What is particularly noticeable is the way the Genesis flood story follows the Gilgamesh flood tale "point by point and in the same order", even when the story permits other alternatives.[7]

Comparative mythology

Mesopotamian

The earliest written flood myth is found in the Mesopotamian Epic of Atrahasis and Epic of Gilgamesh texts. Many scholars believe that Noah and the Biblical Flood story are derived from the Mesopotamian version, predominantly because Biblical mythology that is today found in Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Mandeanism shares overlapping consistency with far older written ancient Mesopotamian story of The Great Flood, and that the early Hebrews were known to have lived in Mesopotamia.[8]

Gilgamesh’s historical reign is believed to have been approximately 2700 BCE,[9] shortly before the earliest known written stories. The discovery of artifacts associated with Aga and Enmebaragesi of Kish, two other kings named in the stories, has lent credibility to the historical existence of Gilgamesh.[10]

The earliest Sumerian Gilgamesh poems date from as early as the Third dynasty of Ur (2100–2000 BC).[11] One of these poems mentions Gilgamesh’s journey to meet the flood hero, as well as a short version of the flood story.[12] The earliest Akkadian versions of the unified epic are dated to ca. 2000–1500 BC.[13] Due to the fragmentary nature of these Old Babylonian versions, it is unclear whether they included an expanded account of the flood myth; although one fragment definitely includes the story of Gilgamesh’s journey to meet Utnapishtim. The “standard” Akkadian version included a long version of the flood story and was edited by Sin-liqe-unninni sometime between 1300 and 1000 BC.[14]

Ancient Greek

Noah has often been compared to Deucalion, the son of Prometheus and Pronoia in Greek mythology. Like Noah, Deucalion is a wine maker or wine seller; he is warned of the flood (this time by Zeus and Poseidon); he builds an ark and staffs it with creatures – and when he completes his voyage, gives thanks and takes advice from the gods on how to repopulate the Earth. Deucalion also sends a pigeon to find out about the situation of the world and the bird returns with an olive branch.

Narrative analysis

According to the documentary hypothesis, the first five books of the Bible (Pentateuch/Torah), including Genesis, were collated during the 5th century BC from four main sources, which themselves date from no earlier than the 10th century BC. Two of these, the Jahwist, composed in the 10th century BC, and the Priestly source, from the late 7th century BC, make up the chapters of Genesis which concern Noah. The attempt by the 5th century editor to accommodate two independent and sometimes conflicting sources accounts for the confusion over such matters as how many pairs of animals Noah took, and how long the flood lasted.[15][16]

Noah's drunkenness

As early as the Classical era, commentators on Genesis 9:20–21 have excused Noah’s excessive drinking because he was considered to be the first wine drinker, the first person to discover the soothing, consoling, and enlivening effects of wine.[17] John Chrysostom, a church father, writes that Noah’s behaviour is defensible: as the first human to taste wine, he would not know its aftereffects: "Through ignorance and inexperience of the proper amount to drink, fell into a drunken stupor".[18]

Philo, a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher, also exonerates Noah by noting that one can drink in two different manners: (1) to drink wine in excess, a peculiar sin to the vicious evil man or (2) to partake of wine as the wise man, Noah being the latter.[19]

In Jewish tradition, rabbis blame Satan for saturating the vine with intoxicating properties from the blood of certain animals, thus Noah behaved not knowing what he was doing.[20]

Curse of Ham

In the field of psychological biblical criticism, J. H. Ellens and W. G. Rollins address the narrative of Genesis 9:18 - 27 that narrates the unconventional behavior that occurs between Noah and Ham. Because of its brevity and textual inconsistencies, it has been suggested that this narrative is a “splinter from a more substantial tale”.[21][22] A fuller account would explain what exactly Ham had done to his father; or why Noah directed a curse at Canaan for Ham’s misdeed; or how Noah came to know what occurred. The narrator relates two facts: (1) Noah became drunken and "he was uncovered within his tent" and (2) Ham "saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without". Thus, these passages revolve around sexuality and the exposure of genitalia as compared with other Hebrew bible texts, such as Habakkuk 2:15 and Lamentations 4:21.[23]

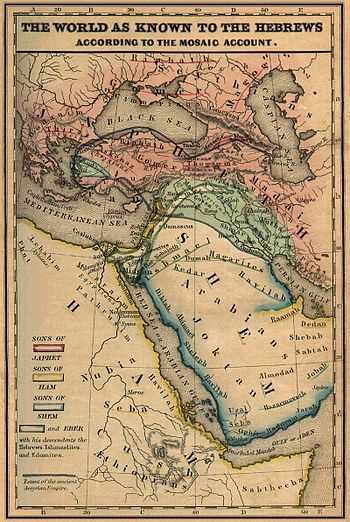

Table of Nations

Genesis 10 sets forth the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, from whom the nations branched out over the earth after the Flood. Among Japheth’s descendants were the maritime nations. (Genesis 10:2–5) Ham’s son Cush had a son named Nimrod, who became the first man of might on earth, a mighty hunter, king in Babylon and the land of Shinar. (Genesis 10:6–10) From there Asshur went and built Nineveh. (Genesis 10:11–12) Canaan’s descendants — Sidon, Heth, the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, the Hivites, the Arkites, the Sinites, the Arvadites, the Zemarites, and the Hamathites — spread out from Sidon as far as Gerar, near Gaza, and as far as Sodom and Gomorrah. (Genesis 10:15–19) Among Shem’s descendants was Eber. (Genesis 10:21)

Religious views

Judaism

The righteousness of Noah is the subject of much discussion among the rabbis.[24] The description of Noah as "righteous in his generation" implied to some that his perfection was only relative: In his generation of wicked people, he could be considered righteous, but in the generation of a tzadik like Abraham, he would not be considered so righteous. They point out that Noah did not pray to God on behalf of those about to be destroyed, as Abraham prayed for the wicked of Sodom and Gomorrah. In fact, Noah is never seen to speak; he simply listens to God and acts on his orders. This led such commentators to offer the figure of Noah as "the man in a fur coat," who ensured his own comfort while ignoring his neighbour. Others, such as the medieval commentator Rashi, held on the contrary that the building of the Ark was stretched over 120 years, deliberately in order to give sinners time to repent. Rashi interprets his father's statement of the naming of Noah (in Hebrew נֹחַ) “This one will comfort (in Hebrew– yeNaHamainu יְנַחֲמֵנו) from our work and our hands sore from the land that the Lord had cursed”,[25] by saying Noah heralded a new era of prosperity, when there was easing (in Hebrew – nahah – נחה) from the curse from the time of Adam when the Earth produced thorns and thistles even where men sowed wheat and that Noah then introduced the plow.

Christianity

According to 2 Peter 2:5, Noah is considered a "preacher of righteousness". Of the Gospels in the New Testament, the Gospel of Luke compares Noah's Flood with the coming Day of Judgement: “Just as it was in the days of Noah, so too it will be in the days of the coming of the Son of Man.”[26]

The First Epistle of Peter compares the saving power of baptism with the Ark saving those who were in it. In later Christian thought, the Ark came to be compared to the Church: salvation was to be found only within Christ and his Lordship, as in Noah's time it had been found only within the Ark. St Augustine of Hippo (354–430), demonstrated in The City of God that the dimensions of the Ark corresponded to the dimensions of the human body, which corresponds to the body of Christ; the equation of Ark and Church is still found in the Anglican rite of baptism, which asks God, "who of thy great mercy didst save Noah," to receive into the Church the infant about to be baptised.

In medieval Christianity, Noah's three sons were generally considered as the founders of the populations of the three known continents, Japheth/Europe, Shem/Asia, and Ham/Africa, although a rarer variation held that they represented the three classes of medieval society – the priests (Shem), the warriors (Japheth), and the peasants (Ham).

In Latter-day Saint theology, the angel Gabriel lived in his mortal life as the patriarch Noah. Gabriel and Noah are regarded as the same individual; Noah being his mortal name and Gabriel being his heavenly name.[27]

Islam

Noah is a highly important figure in Islam, and is seen as one of the most significant prophets of all. The Qur'an contains 43 references to Noah in 28 chapters and the seventy-first chapter, Chapter Noah, is named after him. Noah's narratives largely consist around his preaching as well the story of the Deluge. Noah's narrative lays the prototype for many of the subsequent prophetic stories, which begin with the prophet warning his people and then the community rejecting the message and facing a punishment. Noah is not the first prophet sent to mankind, according to the Qur'an (The first prophet according to Islam is Adam, who was the first man and he was sent to populate earth). Noah has several titles in Islam, based primarily on praise for him in the Qur'an, including True Messenger of Allah (XXVI: 107) and Grateful Servant of Allah (XVII: 3).

The Qur'an focuses on several instances from Noah's life more than others, and one of the most significant events is the Deluge. Allah makes a covenant with Noah just as with Abraham, Moses, Jesus and Muhammad later on (XXXIII: 7). Noah is later reviled by his people and reproached by them for being a mere human messenger and not an angel (X: 72-74). Moreover, the people of Noah mock Noah's words and call him a liar (VII: 62) and even suggest that Noah is possessed by a devil when the prophet ceases to preach (LIV: 9). Only the lowest in the community join Noah in believing in Allah's message (XI: 29), and Noah's narrative further describes him preaching both in private and public. The Qur'an narrates that Noah received a revelation to build an Ark, after his people refused to believe in his message and hear the warning. The narrative goes on to describe that waters poured forth from the Heavens, destroying all the sinners. After the Great Flood ceased, the Ark rested atop Mount Judi (Qur'an 11:44). Also, Islam beliefs deny the idea of Noah to be the first person to drink wine and experience the aftereffects of doing so.

Gnostic

An important Gnostic text, the Apocryphon of John, reports that the chief archon caused the flood because he desired to destroy the world he had made, but the First Thought informed Noah of the chief archon's plans, and Noah informed the remainder of humanity. Unlike the account of Genesis, not only are Noah's family saved, but many others also heed Noah's call. There is no ark in this account; instead Noah and the others hide in a "luminous cloud".

Bahá'í

The Bahá'í Faith regards the Ark and the Flood as symbolic.[28] In Bahá'í belief, only Noah's followers were spiritually alive, preserved in the ark of his teachings, as others were spiritually dead.[29][30] The Bahá'í scripture Kitáb-i-Íqán endorses the Islamic belief that Noah had a large number of companions, either 40 or 72, besides his family on the Ark, and that he taught for 950 (symbolic) years before the flood.[31]

Urantia Book

The Urantia Book considers Noah a real historical person and describes him as "a wine maker of Aram, a river settlement near Erech".[32] Noah is said to have advocated the building of wooden boat houses for the flood season, so that family animals could be kept safe; the people, however, ridiculed him for this.[32] Eventually Noah was proved right when one year an unusually high amount of rainfall occurred in the flood season and destroyed the entire village, save Noah and his immediate family.[32]

While the Urantia Book has Noah as a real person, the biblical narrative involving Noah and his ark and the universal flood is called "an invention of the Hebrew priesthood during the Babylonian captivity." According to the Urantia Book, there has never been a universal, worldwide flood while life has existed.[33]

See also

- Atra-Hasis

- Biblical Criticism

- Manu (Hinduism)

- Noahide Laws

- Nu'u

- Patriarchal Age

- Tomb of Noah

- Ziusudra

References

- ↑ LDS.org: "Book of Mormon Pronunciation Guide" (retrieved 2012-02-25), IPA-ified from «nō´a»

- ↑ Genesis 5:29

- ↑ Genesis 9:20-27

- ↑ Genesis 9:28-29

- ↑ "Chapter X". The Book of Enoch. translated by Robert H. Charles. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. 1917.

- ↑ A. R. George (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-19-927841-1. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ↑ Rendsburg, Gary. "The Biblical flood story in the light of the Gilgamesh flood account," in Gilgamesh and the world of Assyria, eds Azize, J & Weeks, N. Peters, 2007, p. 117

- ↑ Bottero (2001:21–22)

- ↑ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, pages 123, 502

- ↑ Dalley, Stephanie, Myths from Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press (1989), p. 40–41

- ↑ Andrew George, page xix

- ↑ "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature; The death of Gilgameš (three versions, translated)".

- ↑ Andrew George, page 101, “Early Second Millennium BC” in Old Babylonian

- ↑ Andrew George, pages xxiv–xxv

- ↑ Collins, John J. (2004). Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-8006-2991-4.

- ↑ Friedman, Richard Elliotty (1989). Who Wrote the Bible?. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 0-06-063035-3.

- ↑ Ellens & Rollins. Psychology and the Bible: From Freud to Kohut, 2004, (ISBN 027598348X, 9780275983482), p.52

- ↑ Hamilton, 1990, pp. 202–203

- ↑ Philo, 1971, p. 160

- ↑ Gen. Rabbah 36:3

- ↑ Speiser, 1964, 62

- ↑ T. A. Bergren. Biblical Figures Outside the Bible, 2002, (ISBN 1563384116, ISBN 978-1-56338-411-0), p. 136

- ↑ Ellens & Rollins, 2004, p.53

- ↑ "JewishEncyclopedia.com – Noah".

- ↑ Genesis 5:28

- ↑ Luke 17:26

- ↑ "NOAH, BIBLE PATRIARCH". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- ↑ From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, October 28, 1949: Bahá'í News, No. 228, February 1950, p. 4. Republished in Compilation 1983, p. 508

- ↑ Poirier, Brent. "The Kitab-i-Iqan: The key to unsealing the mysteries of the Holy Bible". Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ↑ Shoghi Effendi 1971, p. 104

- ↑ From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi to an individual believer, November 25, 1950. Published in Compilation 1983, p. 494

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Urantia Book, paper 78:7.5

- ↑ Urantia Book, paper 78:7.4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Noah. |

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Noah from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Noah

- MuslimWiki: Nuh

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||