No-Prize

A No-Prize is a faux award given out by Marvel Comics to readers. Originally for those who spotted continuity errors in the comics, the current "No-Prizes" are given out for charitable works or other types of "meritorious service to the cause of Marveldom". As the No-Prize evolved, it was distinguished by its role in explaining away potential continuity errors. Rather than rewarding fans for simply identifying such errors, a No-Prize was only awarded when a reader successfully explained why the continuity error was not an error at all.

History

The No-Prize, originally implemented in 1964, was inspired by the policies of many other comic book publishers of the time — namely, that if a fan found a continuity error in a comic and wrote a letter to the publisher of the comic,[1] he or she would receive a prize of cash, free comics, or something similar.

When readers began pressuring Marvel to start giving out a similar prize,[citation needed] Stan Lee created the No-Prize — basically as a joke by the Marvel staff on the readers. In Fantastic Four #26, Lee ran a contest asking readers to send in their definition of what "the Marvel Age of Comics" really meant. As part of the letter, Lee wrote "there will be no prizes, and therefore, no losers."[2] Originally, the "prize" was simply Lee publishing the letter and informing the letter-writer that he or she had won a No-Prize, which was actually nothing.[3]

Other No-Prize contests asked readers questions and rewarded the most creative responses. For instance, one example asked readers for proof of whether the Sub-Mariner was a mutant or not. Winners had their letters printed along with Lee congratulating them on winning a No-Prize. When fans began demanding No-Prizes for no real reason, Lee took on a new approach. Since other comic companies had given out prizes for pointing out oversights and continuity errors in their books, Lee started doing the same thing, and awarded No-Prizes to people who found errors in the Marvel line of books — which at the time was quite a feat since Marvel was well known for its rigorous continuity.

The No-Prize soon evolved as a reward to those who performed "meritorious service to the cause of Marveldom": readers who first spotted a mistake, or came up with a plausible way to explain a mistake others spotted, or made some great suggestion or performed a service for Marvel in general.[4]

Distribution

The No-Prize had been intended as a reminder for Marvel readers to "lighten up" and read comics for pleasure rather than for prizes, or at least the thrill of being recognized for their efforts.[citation needed] However, letters soon tripled as fans wrote in looking for errors in every comic they could, and suddenly the non-existent prize was in high demand. In addition, many recipients of the "award" began to write Lee and ask why they had not received an actual prize.[citation needed]

In response, in 1967 Lee began mailing No-Prize-winners pre-printed empty envelopes that said "Congratulations, this envelope contains a genuine Marvel Comics No-Prize which you have just won!" But even this was a problem, as some clueless fans wrote back asking where their prize was, even going so far as to suggest their prize had fallen out of the envelope.[citation needed]

Confusion and decline

After Lee stepped down as Marvel editor-in-chief in 1972, Marvel's various editors, who were left in charge of dispensing No-Prizes, developed differing policies toward awarding them. By 1986, these policies ranged from Ralph Macchio's practice of giving them away to anyone who wrote a letter asking for one to Mike Higgins' policy of not awarding them at all. As reported in Iron Man #213 (Dec. 1986), these were the various editors' policies:

- Ann Nocenti (X-Men): "The spirit of the No-Prize is not just to complain and nitpick but to offer an exciting solution. Do that and you will get one from me."

- Carl Potts (Alpha Flight and Power Pack): "If someone points out a major story problem I'm not aware of and solves it to my satisfaction, I'll award a No-Prize. I give away very few."

- Mike Higgins (Starbrand): "No No-Prizes for New Universe no-no's no way!"

- Larry Hama (Conan, G.I. Joe): "No one writes in for them in the Conan books so we don't award them. On G.I. Joe, which I write, I give them to people who get me out of jams if they are very ingenious about it."

- Archie Goodwin (Epic): "We acknowledge our mistakes in print, but Epic Comics doesn't award No-Prizes."

- Bob Budiansky (Secret Wars II): "If someone finds a clever enough explanation for what seems to be a mistake, I'll send them a No-Prize."

- Bob Harras (Incredible Hulk, X-Factor): "My policy is if a certain mistake wouldn't have bothered me when I was a kid, it's not worth a No-Prize. But if someone does really help us out, I'll send them one."

- Don Daley (Captain America): "First I place a temporal statute of limitations on No-Prize mistakes. If the mistake is more than six issues old, it doesn't qualify anymore. Second, I only give them out for things that count, not trivial nitpicking and faultfinding. Third, the explanation should not only be logical but emotionally appealing. I don't award many of them."

- James Owsley (Spider-Man): "We only mail them out to people who send us the best possible explanations for important mistakes. Panels where someone's shirt is colored wrong do not count. We send out the No-Prize envelopes to everyone who gets the same best answer, and sometimes will send out postcards to runners-up who come close."

- Ralph Macchio (Daredevil): "The No-Prize is an honored Marvel tradition. Of course I give them away — for just about any old stupid thing. I have a million of them."[5]

A typical mid-1980s attempt at a No-Prize comes from the letters page of The Incredible Hulk #324 (Oct. 1986), in response to Hulk #321: ". . . On page 12, panel 5, Wonder Man's glasses are knocked off, but in following panels on the next page, he has them on. He didn’t have enough time to get them after they fell off, and Hawkeye’s explosive arrow probably would have destroyed them when it detonated on the Hulk. Never fear, though. I have the solution — while flying down to help Hawkeye, Wonder Man pulled out an extra pair he carries in case of just such emergencies." (Editor Bob Harras awarded the writer a No-Prize.)[6]

Editor Mark Gruenwald believed the quest for No-Prizes negatively impacted the quality of letters sent to comic book letter columns, as readers were becoming more focused on nitpicking and pointing out errors than in responding to the comics' stories themselves. (He even cited one letter which focused on Captain America's glove being yellow in one panel, instead of the correct color red.)[4] Gruenwald then temporarily adopted a new policy, which was to award No-Prizes to readers who not only pointed out an error but also devised a clever explanation as to why it was not "really" an error. (Gruenwald was also known for awarding the "fred-prize" to readers of Captain America.)[7] But in 1986, still believing that the quest for No-Prizes was degrading the quality of reader communication, Gruenwald informed the public that his office would no longer award No-Prizes at all.[8]

By 1989, Marvel was owned by Ronald Perelman, the man who would eventually drive Marvel into bankruptcy.[9] One of the first casualties of the new financial belt-tightening was the No-Prize, considered in one memo to be "a silly, expensive extravagance to mail out."[6]

In 1991, then-Marvel editor-in-chief Tom DeFalco reinstated the No-Prize, introducing the "meritorious service to Marvel above and beyond the call of duty" criteria:

| “ | What constitutes 'meritorious service'? Lots of things could! Like sending a box of comics to the children's wing of a hospital. Or compiling a chronological cross-title index to a character's appearance. Or coming up with an explanation for a major discontinuity or discrepancy. So if you think spotting a misspelled word or miscolored boot is worth a No-Prize, you're living in the wrong decade! This policy is in effect for all Marvel titles whose editors award No-Prizes.[10] | ” |

In the late 1990s, Stan Lee returned to writing the Bullpen Bulletins column. He would answer fan questions, and anyone whose question was used would receive a physical No-Prize.

Digital No-Prize

On July 31, 2006, Marvel executive editor Tom Brevoort instituted the digital No-Prize to be awarded for "meritorious service to Marveldom". The first was awarded on August 12, 2006, to a group of Marvel fans who donated a large number of comics to U.S. servicemembers stationed in Iraq.[11]

Return of the No-Prize

In 2011 Norb Rozek was awarded an actual No-Prize.[12] Norb had previously received a digital No-Prize and was pleasantly surprised by the return of the paper envelope "actual" No-Prize.

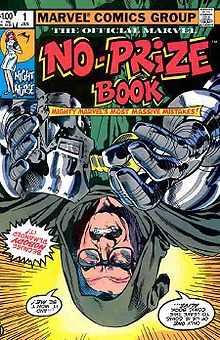

No-Prize book

In 1982, Marvel published a humorous one-shot comic featuring some of their most notorious goofs. Subtitled "Mighty Marvel's Most Massive Mistakes," the book's cover was deliberately printed upside-down. Lee, with the help of artists Bob Camp and Vince Colletta, exposes and pokes fun at typos, misspellings and other errors. Further examples include characters with two left hands, characters looking through the periscope with the eye that has a patch over it and incoherent story lines. There are also famous misnamed characters, such as the text identifying Spider-Man as "Peter Palmer" in Amazing Spider-Man #1, and Doctor Octopus calling him "Super-Man" in Amazing Spider-Man #3.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Carlson, K.C. "KC: LOC," Westfield Comics (Sept. 2008). Accessed Nov. 24, 2008: ". . . Mort Wieisinger's letter columns for the Superman titles . . . were big lists of 'goofs' that popped up in the books, that encouraged the worst kind of fan behavior (and indirectly inspired Stan [Lee] to create the No-Prize!)."

- ↑ Lee, Stan. "Stan's Soapbox," Fantastic Four #26 (Marvel Comics, May 1964).

- ↑ Gruenwald, Mark. "Mark's Remarks," West Coast Avengers #10 letter column (July 1986). Accessed Sept. 29, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gruenwald, Mark. "Avengers Assemble: Mark's Remarks," Avengers #269 (July 1986). Accessed Sept. 29, 2008.

- ↑ Gruenwald, Mark. "Printed Circuits: Mark's Remarks," Iron Man #213 (Dec. 1986).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ruch, John. "Marvel Comics No-Prize," Stupid Question (TM) (Jan. 12, 2004). Accessed Dec. 7, 2008.

- ↑ "Devil's Advocate" (letter's page), Daredevil 228 (March 1986)

- ↑ Gruenwald, Mark. "Printed Circuits: Mark's Remarks," Iron Man #208 (June 1986).

- ↑ Rozanski, Chuck. "Perelman's Team Nearly Destroyed the Entire World of Comics". Mile High Comics. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- ↑ "...No-Prize Newsflash..." The Amazing Spider-Man #347 (May 1991)

- ↑ Brevoort, Tom. "Friday, 5:50," Blah Blah Blog (Aug. 11, 2006). Accessed Sept. 29, 2008.

- ↑ Rozek pointed out that in a recent issue of New Avengers, Nick Fury is shown wearing an eye-patch in a story set in 1959. According to Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos #27 (Feb. 1966), Fury would not lose sight in his eye and start wearing an eye-patch until 1963. The Nick Fury character started out as an army sergeant in stories set during World War II, and had no eyepatch. When Marvel put Fury in stories based in the then-present, in 1965, they gave him an eye-patch and made him a secret agent. However, before they made him a secret agent, there was one story where he guest-starred with the Fantastic Four in a story set in the then-present, and he did not have the eye-patch. So, basically, in Sgt. Fury #27, they created a ludicrous back-story where Fury refuses an eye operation (during World War II) even though he knows it will cost him the vision in his eye one day; which, according to the story, does not happen until 1963 (in other words, after his one appearance in Fantastic Four but before he got the eyepatch in 1965). By this logic, Fury's eye would have still been functional in 1959; it would not fail for four more years. Norb "explained" that perhaps Fury's eye started failing intermittently during the late 1950s-early 1960s, which is why he had an eye-patch in 1959.