Nimravidae

| Nimravidae Temporal range: 40–23Ma Middle Eocene - Late Oligocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hoplophoneus mentalis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | †Nimravidae Cope (1880) |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

The Nimravidae, sometimes known as false saber-toothed cats, is an extinct family of mammalian carnivores that was endemic to North America, Europe, and Asia. Not considered to belong to the true cats (family Felidae), Nimravidae is generally considered closely related and classified as part of suborder Feliformia. Fossils have been dated from the Middle Eocene through the Late Miocene epochs (Bartonian through Tortonian stages, 40.4—7.2 mya), spanning approximately 33.2 million years.[1]

Previously classified as a subfamily of Nimravidae, the barbourofelids have recently been reassigned to their own distinct family Barbourofelidae.[2]

Morphology and evolution

Most nimravids had muscular, low-slung, catlike bodies, with shorter legs and tails than are typical of cats. Unlike extant Feliformia, the Nimravidae had a different bone structure in the small bones of the ear. The middle ear of true cats is housed in an external structure called an auditory bulla, which is separated by a septum into two chambers. Nimravid remains show ossified bullae with no septum, or no trace at all of the entire bulla. It is assumed they had a cartilaginous housing of the ear mechanism.[3]

Although some nimravids physically resembled the sabre-toothed cats of the genus Smilodon, they were not closely related,[4] but evolved a similar form through parallel evolution. They possessed synapomorphies with the barbourofelids in the cranium, mandible, dentition, and postcranium.[5] They also had a flange on the front of the mandible, not as prominent as those on Thylacosmilus, that projected downward as long as the canine tooth.

The ancestors of nimravids and felids diverged from a common ancestor soon after the Caniformia-Feliformia split, in the middle Eocene about 50 million years ago (mya), with a minimum constraint of 43 mya. Recognizable nimravid fossils date from the late Eocene (37 mya), from the Chadronian White River Formation at Flagstaff Rim, Wyoming, to the late Miocene (5 mya). Nimravid diversity appears to have peaked about 28 mya.

Taxonomy

Nimravidae was named by American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in 1880.[6] Its type is Nimravus. It was assigned to Fissipedia by Cope (1889); to Caniformia by Flynn and Galiano (1982); to Aeluroidea by Carroll (1988); to Feliformia by Bryant (1991); and to Carnivoramorpha; by Wesley-Hunt and Werdelin (2005).[7]

Nimravids are placed in tribes by some authors to reflect closer relationships in genera within the family. Some nimravids evolved into large toothed cat-like forms with massive flattened upper canines and accompanying mandibular flanges. Some had dentition similar to felids, or modern cats, with smaller canines. Others had moderately increased canines in a more intermediate relationship between the saber-toothed cats and felids. The upper canines were not only shorter, but also more conical, than those of the true saber-toothed cats (Machairodontinae). These nimravids are referred to as False sabre-tooths.

Not only did nimravids exhibit diverse dentition, but they also showed the same diversity in size and morphology as felids. Some were leopard-sized, others the size of today's lions and tigers, and one had the short face, rounded skull and smaller canines of the modern cheetah.

Natural history

Nimravids appeared in the middle Eocene epoch, about 40 mya, in North America and Asia. The global climate in the middle Eocene was warm and wet, but was trending cooler and drier toward the late Eocene. The lush forests of the Eocene were transitioning to scrub and open woodland. This climatic trend continued in the Oligocene, and nimravids evidently flourished in this environment. North America and Asia were connected and shared much related fauna.[8] Europe in the Oligocene was more an archipelago than a continent, though some land bridges must have existed, for Nimravids spread there, as well.

In the Miocene, the fossil record suggests that many animals suited for forest or woodland were replaced by grazers suited for living in grasslands, so evidently much of North America and Asia became dominated by savanna. Nimravids disappeared along with the woodlands, but survived in relictual humid forests in Europe to the late Miocene. When conditions ultimately changed there in the late Miocene, the last nimravids disappeared about 9 mya.[8]

Classification

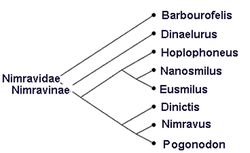

- Family: Nimravidae

- Subfamily Nimravinae

- Genus: Dinictis

- Genus: Dinaelurus

- Genus: Dinailurictis

- Genus: Eofelis

- Genus: Nimravus

- Genus: Pogonodon

- Genus: Quercylurus

- Subfamily Hoplophoninae

- Genus: Eusmilus

- Genus: Hoplophoneus

- Subfamily Nimravinae

References

| Wikispecies has information related to: Nimravidae |

- ↑ PaleoBiology Database: Nimravidae, basic info

- ↑ Morlo, Michael; Stéphane Peigné and Doris Nagel (January 2004). "A new species of Prosansanosmilus: implications for the systematic relationships of the family Barbourofelidae new rank (Carnivora, Mammalia).". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 140 (1): 43. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00087.x.

- ↑ Turner, Alan (1997). The Big Cats and their Fossil Relatives: an illustrated guide. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 234. ISBN 0-231-10228-3.

- ↑ "Meet the Cat Family". The Sunday Observer (Colombo, Sri Lanka: Associated Newspapers of Ceylon). July 16, 2012.

- ↑ Bryant, Harold N. (Feb 1991). "Phylogenetic Relationships and Systematics of the Nimravidae (Carnivora)". Journal of Mammalogy (Lawrence, Kansas: American Society of Mammalogists) 72 (1): 56.

- ↑ Cope, E. D. (Edward Drinker). 1889. "Synopsis of the Families of Vertebrata." The American Naturalist 23:1-29

- ↑ Flynn, John J. and Henry Galiano. 1982. Phylogeny of early Tertiary Carnivora, with a description of a new species of Protictis from the middle Eocene of Northwestern Wyoming. American Museum Novitates.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Prothero, Donald R. (2006). After the Dinosaurs: The Age of Mammals. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 9, 132–134, 160, 167, 174, 176, 198, 222–233. ISBN 978-0-253-34733-6.

- Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2003, 138, 477–493