Nightmare Abbey

| Nightmare Abbey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | Thomas Love Peacock |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Gothic novel, Romance novel, Satire |

| Publisher | T. Hookham Jr. and Baldwin, Craddock & Joy |

Publication date | November 1818 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| ISBN | NA |

| Preceded by | Melincourt |

| Followed by | Maid Marian |

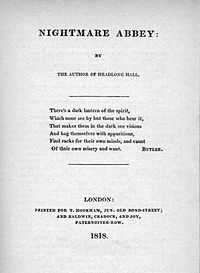

Nightmare Abbey was the third of Thomas Love Peacock's novels to be published. It was written in late March and June 1818, and published in London in November of the same year by T. Hookham Jr of Old Bond Street and Baldwin, Craddock & Joy of Paternoster Row. The novel was lightly revised by the author in 1837 for republication in Volume 57 of Bentley's Standard Novels.

Plot summary

Nightmare Abbey is a Gothic topical satire in which the author pokes light-hearted fun at the romantic movement in contemporary English literature, in particular its obsession with morbid subjects, misanthropy and transcendental philosophical systems. Most of the characters in the novel are based on historical figures whom Peacock wishes to pillory.

Insofar as Nightmare Abbey may be said to have a plot, it follows the fortunes of Christopher Glowry, Esquire, a morose widower who lives with his only son Scythrop in his semi-dilapidated family mansion Nightmare Abbey, which is situated on a strip of dry land between the sea and the fens in Lincolnshire.

Mr Glowry is a melancholy gentleman who likes to surround himself with servants with long faces or dismal names such as Raven, Graves or Deathshead. The few visitors he welcomes to his home are mostly of a similar cast of mind: Mr Flosky, a transcendental philosopher; Mr Toobad, a Manichaean Millenarian; Mr Listless, Scythrop's languid and world-weary college friend; and Mr Cypress, a misanthropic poet. The only exception is the sanguine Mr Hilary, who, as Mr Glowry's brother-in-law, is obliged to visit the abbey from family interests. The Reverend Mr Larynx, the vicar of nearby Claydyke, readily adapts himself to whatever company he is in.

Scythrop is recovering from a love affair which ended badly when Mr Glowry and the young woman's father quarrelled over terms and broke off the proposed match. To distract himself Scythrop takes up the study of German romantic literature and transcendental metaphysics. With a penchant for melancholy, gothic mystery and abstruse Kantian metaphysics, Scythrop throws himself into a quixotic mission of reforming the world and regenerating the human species, and dreams up various schemes to achieve these ends. Most of these involve secret societies of Illuminati. He writes a suitably impenetrable treatise on the subject, which only sells seven copies. But Scythrop is not despondent. Seven is a mystical number and he determines to seek out his readers and make of them seven golden candlesticks with which to illuminate the world. He has a hidden chamber constructed in his gloomy tower as a secret retreat from the enemies of mankind, who will no doubt seek to thwart his attempts at social regeneration.

Meanwhile, however, he is constantly distracted from these projects by his dalliance with two women – the worldly and flirtatious Marionetta and the mysterious and intellectual Stella – and by the constant stream of visitors to the abbey. Things become interesting when Mr and Mrs Hilary arrive with their niece, the beautiful Marionetta Celestina O'Carroll. She flirts with Scythrop, who quickly falls in love; but when she plays hard to get, he retreats to his tower to nurse his wounded heart. Mr Glowry tries to dissuade Scythrop from setting his mind on a woman who not only has no fortune but is insufferably merry-hearted into the bargain. When this fails he turns to Mrs Hilary, who decides in the interests of propriety to take Marionetta away. But Scythrop threatens to drink poison unless his father drops the matter and allows the young woman to stay. Mr Glowry agrees. Unknown to Scythrop, Mr Glowry and Mr Toobad have already come to a secret arrangement to marry Scythrop to Mr Toobad's daughter Celinda; but when Mr Toobad breaks the news to his daughter in London, she goes into hiding.

Back at Nightmare Abbey Marionetta, now sure of Scythrop's heart, torments him for her own pleasure. The other guests pass the time dining, playing billiards and discussing contemporary literature and philosophy, in which discussions Mr Flosky usually takes the lead. A new visitor arrives at the Abbey, Mr Asterias the ichthyologist, who is accompanied by his son Aquarius. The guests discuss Mr Asterias's theory on the existence of mermaids and tritons. It transpires that a report of a mermaid on the sea-coast of Lincolnshire is the immediate reason for Mr Asterias's visit. A few nights later he glimpses a mysterious figure on the shore near the Abbey and is convinced that it is his mermaid, but a subsequent search fails to discover anything of note.

Over the next few days Marionetta notices a remarkable change in Scythrop's deportment, for which she cannot account. Failing to draw the secret out of him, she turns to Mr Flosky for advice, but finds his comments incomprehensible. Scythrop grows every day more distrait, and Marionetta fears that he no longer loves her. She confronts him and threatens to leave him forever. He renews his undying love for her and assures her that his mysterious reserve was merely the result of his profound meditation on a scheme for the regeneration of society. A complete reconciliation is accomplished; even Mr Glowry agrees to the match, as there is still no news of Miss Toobad.

It is only now that we learn the reason for the change in Scythrop's manner. The night on which Mr Asterias spots his mermaid, Scythrop returns to his tower only to find a mysterious young woman there. She calls herself Stella and explains how she is one of the seven people who read his treatise. Fleeing from some "atrocious persecution", she had no friend to turn to until she read Scythrop's treatise and realised that here was a kindred mind who would surely not fail to assist her in her time of need. Scythrop secretes her in his hidden chamber. After several days he finds that his heart is torn between the flirtatious Marionetta and the intellectual Stella, the one worldly and sparkling, the other spiritual and mysterious. Unable to choose between them, Scythrop decides to enjoy both, but is terrified of what might happen should either of his loves learn of the other's existence.

There is a brief and rather inconsequential interruption to the proceedings when Mr Cypress, a misanthropic poet, pays a visit to the Abbey before going into exile. After dinner there is the usual intellectual discussion, after which Mr Cypress sings a tragical ballad, while Mr Hilary and Reverend Larynx enjoy a catch. After the departure of the poet there are reports of a ghost stalking the Abbey, and the appearance of a ghastly figure in the library throws the guests into consternation. The upshot of the matter is that Mr Toobad ends up in the moat.

Inevitably Scythrop's secret comes out. Mr Glowry, who has become suspicious of his son's behaviour, is the immediate cause of it. Confronting Scythrop in his tower, he mentions Marionetta, "whom you profess to love". Hearing this, Stella comes out of the hidden chamber and demands an explanation. The ensuing row comes to the attention of the other guests, who pile into Scythrop's gloomy tower. Marionetta is distraught to discover that she has a rival and faints. But her shock is nothing to that of Mr Toobad, who recognises in Stella none other than his runaway daughter Celinda.

Celinda and Marionetta both renounce their love for Scythrop and leave the Abbey forthwith, determined never to set eyes on him again. The other guests leave (even after the ghost is revealed to have been Mr Glowry's somnambulant steward Crow) and Scythrop becomes depressed. He contemplates suicide like Werther in the Goethe novel, and asks his servant Raven to bring him "a pint of port and a pistol", though he changes his mind and opts instead for "boiled fowl and Madeira". When he renews his determination to make his exit from the world, his father begs him to give him a chance to convince one of the young women to forgive him and return to the Abbey. Scythrop promises to give him one week and not a minute more. When the week is up and there is still no sign of Mr Glowry, Scythrop temporises, convincing himself that his watch is fast. Finally Mr Glowry arrives. He is alone, but he has two letters from Celinda and Marionetta. Celinda wishes Scythrop happiness with Miss O'Carroll and announces her forthcoming marriage to Mr Flosky. Marionetta wishes Scythrop happiness with Miss Toobad and announces her forthcoming marriage to Mr Listless.

Scythrop tears the letters to shreds and consoles himself with the thought that his recent experiences "qualify me take a very advanced degree in misanthropy; and there is, therefore, good hope that I may make a figure in the world." He asks Raven to bring him "some Madeira".

Characters

- Mr Christopher Glowry, Esquire

- The master of Nightmare Abbey; a gentleman of an atrabilarious temperament, a widower and the father of Scythrop Glowry. Mr Glowry regularly suffers from depression and melancholy and cannot abide to see other people cheerful. He surrounds himself with domestics whose only qualification is a long face or a dismal name. His house is open to those of his friends and acquaintances who share his gloomy outlook on life. Mr Glowry is apparently a purely fictional character.

- Scythrop Glowry

- Mr Glowry's only son. Scythrop's forename was that of an ancestor of Mr Glowry's who hanged himself. It is generally accepted that Scythrop is a humorous portrait of Peacock's friend the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. His name is actually derived from the Greek skythrōpos (σκυθρωπος), "of sad or gloomy countenance", which does not suit Shelley; but almost everything else about him confirms this identification. Like Shelley, Scythrop is devoted to social regeneration, and has a penchant for the gothic and the mysterious. Nor is Scythrop conventionally monogamous: he would much prefer to enjoy two mistresses than choose between them. (It has also not escaped the notice of some critics that in both of Shelley's gothic novels Zastrozzi and St Irvyne, the hero is loved by two women at the same time.) Scythrop's impenetrable treatise on social regeneration, Philosophical Gas; or, a Project for a General Illumination of the Human Mind, pokes fun at Shelley's pamphleteering, his ambitions to reform society and his long-held desire to create a utopian society of kindred spirits.

- Miss Marionetta Celestina O'Carroll

- The orphaned daughter of Mr Glowry's youngest sister. She made a runaway love-match with an Irish officer O'Carroll. In one year her fortune was gone; in two years love was gone; and in three years the Irishman was gone. When her mother died, Marionetta was taken in by Mr Glowry's other sister, Mrs Hilary. Marionetta is a blooming and accomplished young lady; she combines in her character the Allegro Vivace of the O'Carrolls and the Andante Doloroso of the Glowries. She is pretty and graceful, and proficient in music. Her conversation is sprightly but light in nature. Moral sympathies have no place in her mind. She is capricious and a coquette. She is generally identified with Harriet Westbrook, a schoolmate of Shelley's sister Hellen. She and Shelley eloped to Scotland and got married in 1811; he was 19 and she was 16 at the time. Three years later Shelley left her and fell in love with and eventually married Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (the future Mary Shelley). In 1816, barely a year before Peacock began Nightmare Abbey, Harriet committed suicide and Shelley married Mary. It has also been noted that in 1814–15 Peacock himself was involved in a love triangle with two women: Marianne de St Croix, to whom he had been attached for many years; and a supposedly rich heiress who fell in love with him. It has been suggested that there is something of Marianne in Marionetta.

- Miss Celinda Toobad

- Mr Toobad's daughter. Celinda's intellectual and philosophical qualities are contrasted with the more conventional femininity of Marionetta. She is the "Penserosa" to Marionetta's "Allegra". Her father, who describes her as being "altogether as gloomy and antithalian a young lady as Mr Glowry himself could desire", sends her to a German convent to finish her education. When her father arranges for her to marry a man she has never met, she absconds. She later turns up at Nightmare Abbey to seek the assistance of Scythrop Glowry, the author of a treatise that has affected her greatly, not realising the Scythrop is none other than her intended husband. She adopts the pseudonym Stella, the name of the eponymous heroine of a drama by Goethe who is involved in a similar love-triangle. There is some uncertainty about the identity of Celinda's historical counterpart. It is often said that she is based upon Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin. In 1814 Shelley abandoned his wife Harriet Westbrook and eloped with the 16-year-old daughter of William Godwin and the late Mary Wollstonecraft, taking with him also Mary's 16-year-old stepsister Jane (later Claire) Clairmont. But Celinda's appearance is quite different from that of the future Mary Shelley, and this has led some commentators to surmise that the person Peacock had in mind when he created Celinda/Stella was in fact Elizabeth Hitchener or Claire Clairmont. Shelley had met Hitchener at Hurstpierpont in Sussex in 1811; the following year she paid a lengthy visit to Shelley and Harriet. Claire had lived with Shelley and Mary for much of the time from their elopement in 1814 until Shelley's death in August 1822; she was undoubtedly very close to Shelley throughout this period, though how close their relationship was is not known.

- Mr Ferdinando Flosky

- A very lachrymose and morbid gentleman, of some note in the literary world. His name is identified in a footnote by Peacock as a corruption of Filosky, from the Greek philoskios (φιλοσκιος), "a lover, or sectator, of shadows". Mr Flosky is a satirical portrait of the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. His criticisms of contemporary literature echo remarks made by Coleridge in his Biographia Literaria; his ability to compose verses in his sleep is a playful reference to Coleridge's account of the composition of Kubla Khan; and his claim to have written the best parts of his friends' books also echoes a similar claim made by Coleridge. Both men are deeply influenced by German philosophy, especially the transcendental idealism of Immanuel Kant. Throughout the novel there are many minor allusions that confirm the Flosky-Coleridge identification. Peacock also satirises Coleridge as Mr Skionar in Crotchet Castle.

- Mr Hilary

- Scythrop's uncle, the husband of Mr Glowry's elder sister. His name is derived from the Latin hilaris, "cheerful", which is an apt description of his outlook on life. If Nightmare Abbey has a character who acts as the author's mouthpiece, it is surely Mr Hilary. His criticisms of the contemporary "conspiracy against cheerfulness" and his advocacy of nature, the music of Mozart and the life-affirming wisdom of the ancient Greeks are distinctly Peacockian qualities.

- Mrs Hilary

- Mr Hilary's wife; a model of propriety and social rectitude.

- Mr Toobad

- A Manichaean Millenarian. That is to say, he is a Manichaean in that he believes that the world is governed by two powers, one good and one evil, and he is a Millenarian in that he believes that the evil power is currently in the ascendant but will eventually be succeeded by the good power – "though not in our time". His favourite quotation is Revelation 12:12: "Woe to the inhabiters of the earth and of the sea! for the devil is come among you, having great wrath, because he knoweth that he hath but a short time". His character is based on J. F. Newton, a member of Shelley's circle.

- Reverend Mr Larynx

- The vicar of Claydyke, a village about ten miles from Nightmare Abbey. Like most clergymen in Peacock's novels, he loves nothing better than "a dinner and a bed at the house of any country gentleman in distress for a companion".

- The Honourable Mr Listless

- A former fellow-collegian of Scythrop's and a fashionable young gentleman. Mr Glowry comes across him on a visit to London and is sufficiently impressed by his gloomy and misanthropical nil curo that he invites him to Nightmare Abbey. He is based on Sir Lumley Skeffington, a friend of Shelley's, and represents the "reading public" (a phrase which occurs frequently in Coleridge's critical works and is thought to have been coined by him).

- Mr Asterias

- An ichthyologist, Mr Asterias is an amateur gentleman scientist. His name is that of the genus of echinoderms to which starfish belong. He is a comical character, but his denunciations of the "inexhaustible varieties of ennui" and his enthusiasm for "the more humane pursuits of philosophy and science" set him apart from the melancholic guests and identify him firmly with Mr Hilary and Peacock himself.

- Mr Cypress

- A misanthropic poet, who is about to go into exile. Mr Cypress is a friend whom Scythrop had known at college and a great favourite of Mr Glowry's. He is based on Lord Byron. Although he only appears briefly in a single chapter, and one which has all the feeling of being an interpolation that does nothing to advance the plot, Mr Cypress is partly the reason Peacock wrote Nightmare Abbey in the first place. Writing to Shelley on 30 May 1818, Peacock notes: "I have almost finished Nightmare Abbey. I think it necessary to 'make a stand' against 'encroachments' of black bile. The fourth canto of Childe Harold is really too bad. I cannot consent to be auditor tantum of this systematical 'poisoning' of the 'mind' of the 'reading public'". Most of Mr Cypress's conversation in Chapter XI is made up of phrases borrowed from the fourth canto of Byron's Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, whose misanthropy Peacock could not stomach.

- Fatout

- Mr Listless's French valet. He also doubles as Mr Listless's walking memory, constantly reminding his master of things that Mr Listless is too listless to bother remembering for himself (such as whether he ever saw a mermaid).

- Miss Emily Girouette

- A young woman with whom Scythrop is for a time in love. He meets her at his uncle Mr Hilary's house in London and the match is favourably viewed by both Mr Glowry and Mr Girouette, but the latter quarrel over terms and the match is called off. Emily and Scythrop pledge their undying love for one another, but within three weeks Emily is married to the Honourable Mr Lackwit. She is usually identified with Harriet Grove, Shelley's cousin and first love. In 1809 Shelley developed an attachment for her, but when she reported his republican and atheistic views to her father, the pair were separated. Shelley poured his feelings of regret into his poetry. Emily's surname, Girouette, is French for "weathercock", which is probably an allusion to the apparent facility with which Harriet transferred her affections elsewhere after she and Shelley were forced to give up their affair. In 1811 Harriet married William Helyar of Sedghill and Coker Court, to whom she bore 14 children.

- Mr Girouette

- Emily Girouette's father. He does not appear in the novel and is mentioned only once.

- The Honourable Mr Lackwit

- Emily Girouette's husband after she and Scythrop become forcibly estranged. He does not appear in the novel and is mentioned only once.

- Raven

- Mr Glowry's butler.

- Crow

- Mr Glowry's steward.

- Skellet

- Mr Glowry's valet. It is Mr Glowry's opinion that he is of French extraction and that his name is a corrupt form of the French squellette, "skeleton".

- Mattocks

- One of Mr Glowry's grooms.

- Graves

- One of Mr Glowry's grooms.

- Diggory Deathshead

- Formerly Mr Glowry's footman. He was hired solely on account of his gloomy name, but Mr Glowry was horrified to discover that he had a round ruddy face, a pair of laughing eyes and was always smiling. By the time Mr Glowry gives him his discharge, he has bedded all the maids and left Mr Glowry with a flourishing colony of young Deathsheads.

Major themes

- The predilection of contemporary poets and novelists for morbid subjects and gothic settings.

- The affected misanthropy, ennui and world-weariness of contemporary writers, philosophers and intellectuals.

- The contemporary interest in philosophical systems that are unworldly, transcendental, and abstruse.

- The conflict between art and science.

- The contrast between the Classical and the Romantic.

Famous passages and quotations

- MR FLOSKY: Modern literature is a north-east wind – a blight of the human soul. I take credit to myself for having helped to make it so. The way to produce fine fruit is to blight the flower. You call this a paradox. Marry, so be it. Ponder thereon.

- There are, indeed, some learned casuists, who maintain that love has no language, and that all the misunderstandings and dissensions of lovers arise from the fatal habit of employing words on a subject to which words are inapplicable; that love, beginning with looks, that is to say, with the physiognomical expression of congenial mental dispositions, tends through a regular gradation of signs and symbols of affection, to that consummation which is most devoutly to be wished; and that it neither is necessary that there should be, nor probable that there would be, a single word spoken from first to last between two sympathetic spirits, were it not that the arbitrary institutions of society have raised, at every step of this very simple process, so many complicated impediments and barriers in the shape of settlements and ceremonies, parents and guardians, lawyers, Jew-brokers, and parsons, that many an adventurous knight (who, to obtain the conquest of the Hesperian fruit, is obliged to fight his way through all these monsters), is either repulsed at the onset, or vanquished before the achievement of his enterprise: and such a quantity of unnatural talking is rendered inevitably necessary through all the stages of the progression, that the tender and volatile spirit of love often takes flight on the pinions of some of the επεα πτεροεντα, or winged words which are pressed into his service in despite of himself.

- MR CYPRESS: Sir, I have quarrelled with my wife; and a man who has quarrelled with his wife is absolved from all duty to his country.

- Scythrop ... threw himself into his arm-chair, crossed his left foot over his right knee, placed the hollow of his left hand on the interior ancle of his left leg, rested his right elbow on the elbow of the chair, placed the ball of his right thumb against his right temple, curved the forefinger along the upper part of his forehead, rested the point of the middle finger on the bridge of his nose, and the points of the two others on the lower part of the palm, fixed his eyes intently on the veins in the back of his left hand, and sat in this position like the immoveable Theseus, who, as is well known to many who have not been at college, and to some few who have, sedet, æternumque sedebit. We hope the admirers of the minutiæ in poetry and romance will appreciate this accurate description of a pensive attitude.

Allusions and references in Nightmare Abbey

It is often said that Peacock's novels are not widely read today on account of the plethora of topical and other allusions with which they are loaded. Peacock himself elucidated a number of these in his own footnotes. The following is a comprehensive list of the works of art and literature to which Peacock alludes or which he quotes or paraphrases in Nightmare Abbey.

- Samuel Butler

- Hudibras

- Upon the Weakness and Misery of Man

- Ben Jonson

- Every Man in His Humour

- François Rabelais

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- William Shakespeare

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Queen Mab

- Proposals for an Association of Those Philanthropists who convinced of the inadequacy of the moral and political state of Ireland to produce benefits which are nevertheless attainable are willing to unite to accomplish its regeneration

- Henry Carey

- Robert Forsyth

- Principles of Moral Science

- C. F. A. Grosse

- Der Genius (translated into English by P. Will as Horrid Mysteries)

- William Godwin

- Alexander Pope

- William Drummond of Logiealmond

- Academical Questions

- Lord Byron

- Voltaire

- Gioachino Rossini

- Giovanni Paisiello

- Samuel Johnson

- Robert Southey

- Roderick, The Last of the Goths

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey

- Omniana

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Dante Alighieri

- The Divine Comedy (translated into English in 1814 by Henry Francis Cary)

- Horace

- Ars Poetica

- Pierre Denys de Montfort

- Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques

- John Milton

- Pliny the Elder

- Henry Joseph Du Laurens

- Le Compère Matthieu

- Edmund Spenser

- Euclid

- Edmund Burke

- Plautus

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Stella

- The Sorrows of Young Werther

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- William Wordsworth

- Goody Blake and Harry Gill (in Lyrical Ballads)

- Virgil

- Pausanias

- Description of Greece

- Anonymous

- Ecclesiastes

- The Royal Kalendar (a Who's Who of the British gentry, published annually from 1767 to 1893 and popularly known as The Red Book)

- The Norfolk Tragedy, a ballad on the story of Babes in the Wood, published in 1595 by Thomas Millington

Literary significance & criticism

Nightmare Abbey is generally considered to be the most lastingly successful of Peacock's novels. Together with four other Peacock novels – Headlong Hall, Melincourt, Crotchet Castle and Gryll Grange – it comprises a matching set of satirical works that are quite exceptional in English literature. As a satirist Peacock owed something to Rabelais, Swift and to Voltaire and various French writers of the 18th century; but as a novelist he seems to owe little if anything to his predecessors. He tended to dramatise where traditional novelists narrated; he is more concerned with the interplay of ideas and opinions than of feelings and emotions; his dramatis personae is more likely to consist of a cast of more or less equal characters than of one outstanding hero or heroine and a host of minor auxiliaries; his novels have a tendency to approximate the Classical unities, with few changes of scene and few if any subplots; his novels are novels of conversation rather than novels of action; in fact, Peacock is so much more interested in what his characters say to one another than in what they do to one another that he often sets out entire chapters of his novels in dialogue form. Plato's Symposium is the literary ancestor of these works, by way of the Deipnosophists of Athenaeus, in which (as in much of Peacock) the conversation relates less to exalted philosophical themes than to the points of a good fish dinner.

Peacock's gentle and bantering sense of satire lacks the caustic indignation of Swift or the cutting edge of Rabelais. Often the targets of his satire are his own friends and acquaintances. It would be more accurate to say that Peacock's satire is directed not at individuals but at the opinions they hold or the popular nostrums they subscribe to. In the preface to the collected edition of his novels (1837) he makes it clear that the characters of his novels are mouthpieces for such things when he lists them under such categories as, perfectibilians, deteriorationists, status-quo-ites, phrenologists, transcendentalists, political economists, theorists in all the sciences, projectors in all arts, morbid visionaries, romantic enthusiasts, lovers of music, lovers of the picturesque and lovers of good dinners.

References

- Peacock, Thomas Love (1969). Wright, Raymond, ed. Nightmare Abbey. Penguin.

External links

The text of Nightmare Abbey is now in the public domain.

| |||||