Nicosia

| Nicosia Λευκωσία (Greek) Lefkoşa (Turkish) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital city | |||

| |||

| |||

Nicosia | |||

| Coordinates: 35°10′N 033°22′E / 35.167°N 33.367°ECoordinates: 35°10′N 033°22′E / 35.167°N 33.367°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| District | Nicosia District | ||

| Status | Recognised by the international community[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] as territory of the Republic of Cyprus (northern half under control of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, only recognised by Turkey) | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Constantinos Yiorkadjis (Ind.) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Capital city | 111 km2 (43 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 220 m (720 ft) | ||

| Population (2011 (south), 2006 (north)) | |||

| • Capital city | 310,355 | ||

| • Density | 2,800/km2 (7,200/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro |

239,277 (south) 71,078 (north) | ||

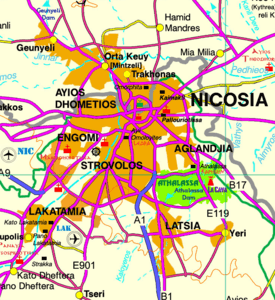

| (South includes municipalities of Nicosia (only the south part), Agios Dometios, Egkomi, Strovolos, Aglantzia, Lakatameia, Anthoupolis, Latsia and Yeri.[8] North includes Mandres (Hamitköy), Mia Milia (Haspolat), Gönyeli (Kioneli), Gerolakkos (Alayköy) and Kanlıköy (Kanli) as well as the northern part of Nicosia[9]) | |||

| Demonym | Nicosian | ||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+02:00) | ||

| Post code | 1010–1107 | ||

| Area code(s) | +357 22 | ||

| ISO 3166 code | CY-01 | ||

| Website |

| ||

Nicosia (/ˌnɪkəˈsiːə/ NIK-ə-SEE-ə; Greek: Λευκωσία; Turkish: Lefkoşa) is the capital and largest city on the island of Cyprus, as well as its main business centre.[10] After the collapse of the Berlin Wall, Nicosia became the last remaining divided capital in the world,[11] with the southern and the northern portions divided by a Green Line.[12] It is located near the centre of the island, on the banks of the River Pedieos.

Nicosia is the capital and seat of government of the Republic of Cyprus. It is the southeasternmost capital of the EU member states. The northern part of the city functions as the capital of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, a disputed region recognized only by Turkey, and which the international community recognises as Cypriot territory under Turkish occupation, and has done so since the Turkish invasion in 1974.

Through the years Nicosia has established itself as the island's financial capital and its main international business centre. The city is ranked as the 5th richest city in the world in per capita income terms.[13]

In the past few years Nicosia has seen remarkable progress regarding its infrastructure with the most remarkable being the central Eleftheria square currently in progress.[14]

Landmarks

Ledra Street is in the middle of the walled city. The street has historically been the busiest shopping street of the capital and adjacent streets lead to the most lively part of the old city with narrow streets, boutiques, bars and art-cafés. The street today is a historic monument on its own. It is about 1 km (0.6 mi) long and connects the south and north parts of the old city. During the EOKA struggle that ran from 1955–1959, the street acquired the informal nickname The Murder Mile in reference to the frequent targeting of the British colonialists by nationalist fighters along its course.[15][16] In 1963, during the outbreak of hostilities between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities, following the announcement of amendments to the Cypriot Constitution, Turkish Cypriots withdrew to the northern part of Nicosia which became one of the many Turkish Cypriot enclaves which existed throughout the island. Various streets which ran between the northern and southern part of the city, including Ledra Street, were blockaded. During the Turkish army invasion of Cyprus in 1974, Turkish troops occupied northern Nicosia (as well as the northern part of Cyprus). A buffer zone was established across the island along the ceasefire line to separate the northern Turkish controlled part of the island, and the south. The buffer zone runs through Ledra Street. After many failed attempts on reaching agreement between the two communities, Ledra Street was reopened on 3 April 2008.

To the east of Ledra Street, Faneromeni Square was the centre of Nicosia before 1974. It hosts a number of historical buildings and monuments including Faneromeni Church, Faneromeni School, Faneromeni Library and the Marble Mausoleum. Faneromeni Church, is a church built in 1872 in the stead of another church located at the same site, constructed with the remains of La Cava castle and a convent. There rest the archbishop and the other bishops who were executed by the Ottomans in the Saray Square during the 1821 revolt. The Palace of the Archbishop can be found at Archbishop Kyprianos Square. Although it seems very old, it is a wonderful imitation of typical Venetian style, built in 1956. Next to the palace is the late Gothic Saint John cathedral (1665) with picturesque frescos. The square leads to Onasagorou Street, another busy shopping street in the historical centre.

The walls sourrounding the old city have three gates. In The Kyrenia Gate which was responsible to the transport to the north, and especially Kyrenia, the Famagusta Gate which was responsible for the transport from Famagusta, Larnaca and Limassol and Karpasia, and the Paphos Gate for transport to the west and especially Paphos. All three gates are well-preserved.[17]

The historical centre is clearly present inside the walls, but the modern city has grown beyond. Presently, the main square of the city is Eleftheria (Freedom) Square, with the city hall, the post office and the library. The square which is currently under renovation, connects the old city with the new city where one can find the main shopping streets such as the prestigious Stasikratous Street, Themistokli Dervi Avenue and Makarios Avenue.

Nicosia is also known for its fine museums. The Archbishop's Palace contains a Byzantine museum containing the largest collection of religious icons on the island. Leventis Municipal Museum is the only historical museum of Nicosia and revives the old ways of life in the capital from ancient times up to our days. Other interesting museums include the Folk Art Museum, National Struggle Museum (witnessing the rebellion against the British administration in the 1950s), Cyprus Ethnological Museum (House of Dragoman Hadjigeorgakis Kornesios, 18th century) and the Handicrafts Centre.

Nicosia also hosts an Armenian achbishopship, a small Buddhist temple and also the Maronite arbishopship and convent. Cyprus is the second most important country for the Maronite people worldwide after Lebanon.[citation needed] During the Pope's visit to the island in June 2010, the Pontiff resided inside the convent.

History

Ancient times

Nicosia has been in continuous habitation since the beginning of the Bronze Age 2500 years BC, when the first inhabitants settled in the fertile plain of Mesaoria.[18] Nicosia later became a city-state known as Ledra or Ledrae, one of the twelve kingdoms of ancient Cyprus built by Achaeans after the end of the Trojan War. [citation needed] Remains of old Ledra today can be found in the Ayia Paraskevi hill in the south east of the city. We only know about one king of Ledra, Onasagoras. The kingdom of Ledra was destroyed early. Under Assyrian rule of Cyprus, Onasagoras, was recorded as paying tribute to Esarhaddon of Assyria in 672 BC. Rebuilt by Lefkonas, son of Ptolemy I around 300 BC, Ledra is described as a small and unimportant town, also known as Lefkotheon. The main activity of the town inhabitants was farming. During this era, Ledra did not have the huge growth that the other Cypriot coastal towns had, which was primarily based on trade.[19]

Roman and Byzantine times

In Byzantine times the town was also referred to as Lefkousia and also as Kallinikisis. In the 4th century AD, the town became the seat of bishopship, with bishop Saint Tryphillius (Trifillios), a student of Saint Spyridon.[20]

After the destruction of Salamis by Arab raids in 647, the existing capital of Cyprus, Nicosia became the capital of the island around 965, when Cyprus rejoined the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines moved the islands administration seat to Nicosia, primarily for security reasons as coastal towns were often suffering from raids. Since then it remains as the capital of Cyprus. Nicosia had acquired a castle and was the seat of the Byzantine governor of Cyprus. The last Byzantine governor of the Island was Isaac Comnenus who declared himself emperor of the island and ruled the island from 1183–1191.[21]

Medieval times

On his way to the Holy Land during the Third Crusade in 1187, Richard I of England fleet was plagued by storms. He himself stopped first at Crete and then at Rhodes. Three ships continued on, one of which was carrying Queen Joan of Sicily and Berengaria of Navarre, Richard's bride-to-be. Two of the ships were wrecked off Cyprus, but the ship bearing Joan and Berengaria made it safely to Limassol. Joan refused to come ashore, fearing she would be captured and held hostage by Isaac Comnenus, who hated all Franks. Her ship sat at anchor for a full week before Richard finally arrived on 8 May. Outraged at the treatment of his sister and his future bride, Richard invaded.[22]

Richard laid siege to Nicosia. Richard finally met and defeated Isaac Comnenus at Tremetousia. Richard became ruler of the island but sold the island to the Knights Templar. The Knights Templar ruled the island having bought it from Richard the Lionheart for 100.000 gold byzantiums. Their seat was the castle of Nicosia. On Easter day on 11 April 1192 the people of Nicosia revolted and drove the Knights Templar off the city. Having driven the Knights Templar away, fearing their return the Nicosians demolished the castle of the city almost to its foundations.[23]

Guy of Lusignan, King of Jerusalem, bought Cyprus from the Knights Templar and brought many noble men and other adventurers, from France, Jerusalem, Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch and Kingdom of Armenia, to the island. Guy shared the land he had bought among them and Nicosia became capital off their kingdom. He imposed harsh feudal system and the vast majority of Cypriots were reduced to the status of serfs.[24] The Frankish rule of Cyprus started from 1192 and lasted until 1489. During this time, Nicosia was the capital of the medieval Kingdom of Cyprus, the seat of Lusignan kings, the Latin Church and the Frankish administration of the island. During the Frankish rule, the walls of the city were built along with many other palaces and buildings, including the gothic Saint Sofia Cathedral. The tombs of the Lusignan kings can be found there. The first Lusignan castle was built during the reign of King Henry I, 1211. On seals of the king and his mother Alix in 1234, a castle with one or two towers is depicted surrounded with the inscription "CIVITAS NICOSIE".[25] The exonym Nicosia appeared with the arrival of the Lusignans. The French-speaking Crusaders either could not, or did not care to, pronounce the name Lefkosia, and tended to say "Nicosie" translated into Italian and then internationally known as "Nicosia". [citation needed]

In 1374 Nicosia was occupied and ravaged by the Genoans and in 1426 from the Mamelukes of Egypt. [citation needed]

In 1489, when Cyprus came under Venetian rule, Nicosia became their administrative center and the seat of the Republic of Venice. The Venetian Governors saw it as a necessity for all the cities of Cyprus to be fortified due to the Ottoman threat.[26] In 1567 Venetians built the new fortifications of Nicosia, which are well-preserved until today, demolishing the old walls built by the Franks as well as other important buildings of the Frankish era including the King's Palace, other private palaces and churches and monasteries of both Orthodox and Latin Christians.[27] The new walls took the shape of a star with eleven bastions. The design of the bastion is more suitable for artillery and a better control for the defenders. The walls have three gates, to the North Kyrenia Gate, to the west Paphos Gate and to the east Famagusta Gate.[27] The river Pedieos used to flow through the Venetian walled city. In 1567 it was later diverted outside onto the newly built moat for strategic reasons, due to the expected Ottoman attack.[28]

Ottoman rule

_-_TIMEA.jpg)

On 1 July 1570, the Ottomans invaded the island. On 22 July, Piyale Pasha having captured Paphos, Limassol and Larnaca marched his army towards Nicosia and laid siege to the city.[29] The city managed to last 40 days under siege until its fall on 9 September 1570. Some 20,000 residents died during the siege and every church, public building, and palace was looted.[30] After its siege it was reported that the walls were ruined and Nicosia retained very few inhabitants. The main Latin churches were converted into mosques, such as the conversion of Saint Sofia Cathedral. From 1570 when the Ottomans took over Nicosia, the old river bed through the walled city was left open and was used as a dumping ground for refuse, where rainwater would rush through clearing it temporarily.[28]

Nicosia was the seat of the Pasha, the Greek Archbishop, the Dragoman and the Qadi. The Palazzo del Governo of Venetian times became the seat of the Pasha, the governor of Cyprus, and the building was known as the Konak or Seraglio (Saray). The square outside was known as Seraglio Square or Sarayonu (literally front of the Saray), as it is known to the present day. The saray was demolished in 1904 and the present block of Government Offices built on the site.[31]

When the newly settled Turkish population arrived they generally lived in the north of the old riverbed. Greek Cypriots remained concentrated in the south, where the Archbishopric of the Orthodox Church was built. Other ethnic minority groups such as the Armenians and Latins came to be settled near the western entry into the city at Paphos Gate.[32]

The names of the 12 quarters into which Nicosia was originally divided at the time of the Ottoman Conquest are said to be derived from the 12 generals in command of divisions of the Ottoman army at the time. Each general being posted to a quarter, that quarter was known by his name as follows:

1. General Ibrahim Pasha.

2. General Mahmoud Pasha.

3. General Ak Kavuk Pasha. (This is a nickname meaning "white cap.")

4. General Koukoud Effendi.

5. General Arab Ahmed Pasha.

6. General Abdi Pasha, known as Chavush (Sergeant) from which rank he was probably promoted.

7. General Haydar Pasha.

8. General Karamanzade (son of a Caramanian, other names not given).

9. General Yahya Pasha (now known as the Phaneromeni Quarter).

10. General Daniel Pasha (name of quarter changed subsequently to Omerie in honour of the Caliph Omar who stayed there for a night when in Cyprus).

The names of the generals in command of these quarters have been lost:

11. Tophane (Artillery Barracks)

12. Nebetkhane, meaning meaning police station or quarters of the patrol.

[31]

Later the number of neighbourhoods was increased to 24. Each neighbourhood was organized around a mosque or a church, where mainly the respective Moslem and Christian communities lived.[33]

British administration

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1881 | 11,536 | — |

| 1891 | 12,515 | +8.5% |

| 1901 | 14,481 | +15.7% |

| 1911 | 16,052 | +10.8% |

| 1921 | 11,831 | −26.3% |

| 1931 | 23,324 | +97.1% |

| 1946 | 34,485 | +47.9% |

| 1960 | 45,629 | +32.3% |

| Source for 1881-1960.[34] | ||

On 5 July 1878 the administration of the island was officially transferred to Great Britain. On 31 July 1878, Garnet Wolseley, the first High Commissioner, arrived in Nicosia. He immediately established a skeletal administration by sending officers to each district to supervise the administration of justice and obtain all possible information about the area. Garnet Wolseley immediately established a Post Office at his camp at Kykko Metochi monastery outside Nicosia. Garnet Wolseley lived at ‘Monastery Camp' until a prefabricated residence had been built for him near Strovolos on the site of today's Presidential Palace.[35] The old Ottoman administrative headquarters (the Saray) was replaced in 1904 by a new building containing Law Courts, the Land Registry, and the Forestry, Customs, and Nicosia Commissioner's Offices.[31] Adjacent was the Nicosia Police headquarters, while opposite were the General Post Office and the Telegraph Office.[36] A Venetian Column, previously in a fenced courtyard near the Saray,[37] was restored on a new site in the summer of 1915 in the middle of Saray Square. The Nicosia column was presumably erected in compliment to the reigning Doge Francesco Donati about the year 1550.[31]

Just after the British Occupation a Municipal Council was constituted in Nicosia in 1882 for the general administration of public affairs within the city and for a certain area without the walls, under the presidency of a Mayor.[31] The first municipal offices were in Municipality Square (now the central municipal market), but in 1944 the offices were transferred temporarily to the d'Avila bastion and in 1952 this was made permanent with a decision to renovate the building[38]

At the time of British administration, Nicosia was still contained entirely within its Venetian walls. Although full of private gardens and amply supplied with water carried to public fountains in aqueducts, the streets remained unpaved and just wide enough for a loaded pack animal. In 1881, macadamized roads through the town were completed to connect with the main roads to the coastal towns but no roads were asphalted until after World War I. A series of openings in the Venetian walls provided direct access to areas beyond the walls. The first opening was cut in the Paphos Gate in 1879. The Limassol or Hadjisavva opening, now Eleftheria Square linked the city to the government offices in 1882. An opening was made at the Kyrenia Gate in 1931 after one of Nicosia's first buses proved too high to go through the original gate. Many more openings followed. During the post-war period the villages around Nicosia began to expand. By 1958 they had been engulfed in suburbia. Only Strovolos and Aglandja maintained separate physical identities, chiefly because of intervening state-owned land. By this time, the old city was increasingly given over to shops and workshops."[39]

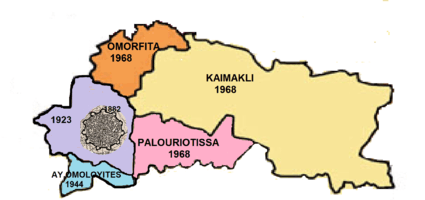

Originally aligned with the walls, the municipal limits were extended in June 1882 to "a circle drawn at a distance of five hundred yards beyond the salient angles of the bastions of the fortifications".[39] In 1923 the municipal limits were extended further (see map) and this new area was divided among several of the existing intramural Neighbourhoods.[40] The next extension came in 1944 with the annexation of Ayii Omoloyites and finally, shortly after independence, Palouriotissa, Kaimakli and Omorfita were annexed to the city in 1968.[41]

In 1955 an armed struggle against the British rule began aiming to unite the island with Greece, Enosis. The struggle was led by EOKA, a Greek Cypriot nationalist military resistance organisation,[42][43] and supported by the vast majority of Greek Cypriots. The unification with Greece failed and instead the independence of Cyprus was declared in 1960. During the period of the struggle, Nicosia was the scene of violent protests against the British rule.[citation needed]

Independence and division

In 1960 Nicosia became the capital of the Republic of Cyprus, a state established by the Greek and Turkish Cypriots. In 1963, the Greek Cypriot side proposed amendments to the constitution, which were rejected by the Turkish Cypriot community.[44] During the aftermath of this crisis, on 21 December 1963, intercommunal violence broke out between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. Nicosia was divided into Greek and Turkish Cypriot quarters with the Green Line, named after the colour of the pen used by the United Nations officer to draw the line on a map of the city.[45] This resulted in Turkish Cypriots withdrawing from the government, and following more intercommunal violence in 1964, a number of Turkish Cypriots moved to the Turkish quarter of Nicosia, causing serious overcrowding.[46]

On 15 July 1974, there was an attempted coup d'état led by the Greek military junta to unite the island with Greece. The coup ousted president Makarios III and replaced him with pro-enosis nationalist Nikos Sampson.[47]

On 20 July 1974, the Turkish army invaded the island on the pretext of restoring the constitutional order of the Republic of Cyprus. However, even after the restoration of constitutional order and the return of Archbishop Makarios III to Cyprus in December 1974, the Turkish troops remained on the island occupying the northeastern portion of the island.[48] The invasion was given the codename Operation Attila and included two phases.

The second phase of the Turkish invasion was performed on 14 August 1974, where the Turkish army advanced their positions, eventually capturing a total of 37% of Cypriot territory including the northern part of Nicosia and the cities of Kyrenia and Famagusta. The fighting left the island with a massive refugee problem. Out of a population of 600,000, an estimated 200,000 Greek-Cypriots had been uprooted and forced to flee south of the Attila line, while an estimated 60,000 Turkish-Cypriots remained south of the Attila line, uncertain of their fate.[49]

On 13 February 1975 the Turkish Cypriot community declared the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus in the area occupied by Turkish forces.[50] On 15 November 1983, Turkish Cypriots proclaimed their independence as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

On 23 April 2003, the Ledra Palace crossing was opened through the Green Line, the first time that crossing was allowed since 1974.[51] This was followed by the opening of Ayios Dometios/Metehan crossing point on 9 May 2003.[52] On 3 April 2008, the Ledra Street crossing was also reopened.[53]

The Turkish invasion, the continuous occupation of Cyprus as well as the self-declaration of independence of the TRNC have been condemned by several United Nations Resolutions adopted by the General Assembly and the Security Council. The Security Council is reaffirming their condemnation every year.[54]

Local Government

Governance of the metropolitan area

The population of the conurbation is 300,000 (2011 census, plus Turkish Cypriot administered census of 2006) of which 100,000 live within the Nicosia municipal area. Because Nicosia municipality has separate communal municipal administrations, the population of Strovolos (67,904 (2011 Census)) is actually the largest of all the local authorities in Greater Nicosia.

Within Nicosia municipality, most of the population resides in the more recently annexed outlying areas of Kaimakli, Pallouriotissa, Omorfita and Ayii Omoloyites.

There is no metropolitan authority as such for Greater Nicosia and various roles, responsibilities and functions for the wider area are undertaken by the Nicosia District administration, bodies such as the Nicosia Water Board and, to some extent, Nicosia municipality.

The Nicosia Water Board supplies water to the following municipalities: Nicosia, Strovolos, Aglandjia, Engomi, Ay. Dometios, Latsia, Geri and Tseri. The board consists of three persons nominated by the Council of each municipality, plus three members appointed by the government, who are usually the District Officer of Nicosia District, who chairs the Board, the Accountant General and the Director of the Water Department. The board also supply Anthoupolis and Ergates, for whom the government provide representatives. Thus the board is in the majority controlled by the municipalities of Greater Nicosia in providing this vital local government service.[55]

The Nicosia Sewerage Board, is likewise majority controlled by the municipalities of Greater Nicosia. It is chaired ex officio by the Mayor of Nicosia and consists of members chosen by the municipalities of Nicosia (6 members), Strovolos (5 members), Aglandjia (2 members), Lakatamia (2 members), Ay. Dometios (2 members), Engomi (2 members), Latsia (1 member). The sewage treatment plant is at Mia Milia. The Nicosia Sewerage System serves a population of approximately 140,000 and an area of 20 km2 (8 sq mi). Approximately 30% of the influent is contributed by the Turkish Cypriot Side.[56]

Public transport is not controlled by the local authorities, but comes under the Nicosia District administration, which is an arm of the Ministry of the Interior. Transport services (primarily bus and taxi) are provided by an agency of the Nicosia District (OSEL) or private companies.[57]

Nicosia Municipality

The Nicosia Municipality is responsible for all the municipal duties within the walled city and the immediately adjacent areas. The Constitution states that various main government buildings and headquarters must be situated within the Nicosia municipal boundaries.[58] However separate municipalities are prescribed by the constitution for in the five largest towns, including Nicosia,[59] and in the case of Nicosia the separate administration was established in 1958. The Turkish Municipal Committees (Temporary Provisions) Law, 1959[60] established a municipal authority run by a "Turkish Municipal Committee", defined as "the body of persons set up on or after the first day of July, 1958, in the towns of Nicosia, Limassol, Famagusta, Larnaca and Paphos by the Turkish inhabitants thereof for the purpose of performing municipal functions within the municipal limits of such towns".The Nicosia Turkish Municipality, founded in 1958, carries out municipal duties in the northern and north-western part of city.[61] The remaining areas, in the south and east of the city, are administered by Nicosia Municipality.

According to the constitution of Cyprus, Nicosia Municipality was divided into a Greek and Turkish sector with two Mayors: a representative of the Greek community which was the majority, and a second one representing the Turkish community. The Mayors and the members of the Council were appointed by the President of the Republic. Since 1986, the Mayors and members of the Council are elected. The Mayor and the Municipal Councillors are elected by direct popular suffrage but into separate ballots – one for the Mayor and the other for all the Councillors. Municipal elections are held every five years.

The Municipality of Nicosia is now headed by the Mayor, who is Constantinos Yiorkadjis supported by Democratic Rally and Democratic Party and the council composed of 26 councilors, one of who is Deputy Mayor.

The Mayor and the Councillors exercise all the powers vested in them by the Municipal Corporation Law. Sub-committees consisting of members of the Municipal Council act only on an advisory level and according to the procedures and regulations issued by the Council.

The Mayor is the executive authority of the Municipality, exercising overall control and managing the Municipal Council. The Council is responsible for appointing personnel employed by the Municipality. All municipalities in the Republic of Cyprus are members of the Union of Cyprus Municipalities. The executive Committee is the governing organ of the Union. This Committee is appointed from among the representatives of the Municipalities for a term of two and a half years. The Mayor of Nicosia is the President of the Union and the Chairman of the Executive Committee.

Nicosia Turkish Municipality

The first attempt to establish a Nicosia Turkish Municipality was made in 1958. In October 1959, the British Colonial Administration passed the Turkish Municipality Committees law. In 1960 with the declaration of independence of Cyprus, the Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus gave Turkish Cypriots the right to establish their own municipality.[62][63][64] As negotiations between the two sides to establish separate municipalities failed in 1962, implementing legislation was never passed.[65][66] Since the complete division of Nicosia following the Turkish Invasion in 1974, the Nicosia Turkish Municipality has become the de facto local authority of northern Nicosia. The Nicosia Turkish Municipality is a member the Union of Cyprus Turkish Municipalities.[67] The current mayor is Kadri Fellahoğlu from Republican Turkish Party (CTP)Cemal Metin Bulutoğluları.

Other Municipalities in Greater Nicosia

Until 1986 there were no suburban municipalities. Then, following the procedures in the Municipal Law 111/1985, Strovolos, Engomi, Ay. Dometios, Aglandjia, Latsia and Lakatamia were erected into municipalities.[68] Each municipal council has the number of members described in the Municipal Law 111/1985 depending on the population figures. All members of the council are elected directly by the people for a period of 5 years.

Administrative Divisions

Nicosia within the city limits is divided into 29 administrative units, according to the latest census. This unit is termed in English as quarter, neighbourhood, parish, enoria or mahalla. These units are: Ayios Andreas (Tophane), Trypiotis, Nebethane, Tabakhane, Phaneromeni, Ayios Savvas, Omerie, Ayios Antonios (St. Anthony), St. John, Taht-el-kale, Chrysaliniotissa, Ayios Kassianos (Kafesli), Kaïmakli, Panayia, St Constantine & Helen, Ayioi Omoloyites, Arab Ahmet, Yeni Jami, Omorfita, Ibrahim Pasha, Mahmut Pasha, Abu Kavouk, St. Luke, Abdi Chavush, Iplik Bazar & Korkut Effendi, Ayia Sophia, Haydar Pasha, Karamanzade,[69] and Neapoli (separated from Ibrahim Pasha 25 Jan 2010[70]).Some of the these units were previously independent Communities (village authorities). Ayioi Omoloyites was annexed in 1944, while Kaïmakli and Omorfita were annexed in 1968. Pallouriotissa, also annexed in 1968, was subsequently divided into the neighbourhoods of Panayia, and St Constantine & Helen.[71]

The municipality of Strovolos, established in 1986, is the second largest municipal authority in Cyprus in terms of population after Limassol and encompasses the southern suburbs of the capital immediately adjacent to Nicosia municipality. Strovolos is divided into six parishes: Chryseleousa, Ayios Demetrios, Apostle Barnabas and Ayios Makarios, Ayios Vasilios, Kyprianos and Stavros.[72]

Beyond Strovolos on the south-western fringes of the metropolis lies the municipality of Lakatamia, created in 1986 out of the two Communities (village authorities) of Lower Lakatamia and Upper Lakatamia . After being declared a municipality Lakatamia was, for administrative purposes, divided into the following four parishes: Ayia Paraskevis, St. Nicholas, Ayios Mamas, Archangel-Anthoupolis. Contrary to other Municipalities, Lakatamia Municipality has its own water supply (Lakatamia Water Board). It has jurisdiction over the water supply and sees to the construction, maintenance and functioning of water supply systems within its boundaries.[73]

South of Strovolos lies the municipality of Latsia, established in 1986. Latsia is divided into three parishes: St. George (covering most of the area of Latsia), Ayios Eleftherios (covering the Ayios Eleftherios refugee housing estate) and Archangel Michael (covering the refugee self-housing estate of that name).[74]

East of Latsia lies Yeri, which became a municipality in 2011. The built up area of Yeri just touches Latsia near their mutual boundary and thus the new municipality is conurbated with Nicosia.

The municipality of Aglandjia, established in 1986, encompasses the south-eastern suburbs of the capital immediately adjacent to Nicosia municipality. The Nicosia-Limassol highway forms the boundary with Strovolos to the west. The name of the municipality has various spellings, but derives from the Turkish word 'Eğlence - Entertainment'. The older English spelling is Eylenja.[75]

The western suburbs are encompassed in the municipalities of Ayios Dometios and Engomi, both established in 1986. The municipality of Ayios Dometios is divided into the parishes of St. George and St. Paul.

The town of Geunyeli(Gonyeli or Kioneli) is now conurbated with the northern suburbs. Previously a village authority, it now functions as a municipality[76] within the same area[77] Geunyeli is divided into the Neighbourhoods of Baraj (barrage), Çarşı, Baz and Yeni Kent (new town).[78]

The suburbs immediately to the north of the city have not been erected into municipalities. The village authority of Hamid Mandres[79] continued to exist until 1 September 2008, when it was included within the borders of Nicosia Turkish Municipality[80] and is now functioning as a Nicosia neighbourhood headed by a Mukhtari[81]

Ortakeuy Village authority[82] has similarly been redefined as a neighbourhood of Nicosia Turkish Municipality.

After the invasion the inhabitants of Mia Milia were displaced to other parts of Cyprus[83] together with their Village Council, which continues to operate in exile,[84] although the Nicosia Turkish Municipality considers it one of its neighbourhooods[85]

The ethnically mixed Village of Trakhonas has suffered several displacements of both its Greek and Turkish Cypriot inhabitants since the 1960s and since the invasion has been heavily urbanised.[86] It does not currently function as a local government unit[87]

The settlement of Anthoupolis is an enclave created within Lakatamia after the invasion of 1974 and is directly administered by the government and not the municipality within which it is situated.

Table of Administrative Divisions

| Code | Name | Loc. auth. | CY Pop. 2011 | TC Pop. 2011 |

CY Ctrl. | TC Ctrl. |

Pop. 1946 | GC 1946 | TC 1946 | On map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | Nicosia | Mun | 55,014 | 49,868 | P | P | 34,485 | 60% | 30% | |

| 1000-01 | Ayios Andreas (Tophane) | Neigh | 5,767 | Y | 3,012 | 74% | 5% | AA/T | ||

| 1000-02 | Trypiotis | Neigh | 2,158 | Y | 3,247 | 92% | 1% | Try | ||

| 1000-03 | Nebethane | Neigh | 189 | Y | 520 | 84% | 4% | Ne | ||

| 1000-04 | Tabakhane | Neigh | 299 | Y | 757 | 93% | 3% | TH | ||

| 1000-05 | Phaneromeni | Neigh | 512 | Y | 1,088 | 98% | 1% | Ph | ||

| 1000-06 | Ayios Savvas | Neigh | 581 | Y | 1,266 | 96% | 3% | ASa | ||

| 1000-07 | Omerie | Neigh | 206 | Y | 1,193 | 77% | 21% | Om | ||

| 1000-08 | Ayios Antonios | Neigh | 5,801 | Y | 2,090 | 98% | 0% | AAn | ||

| 1000-09 | Ayios Ioannis | Neigh | 221 | Y | 1,436 | 96% | 4% | AI | ||

| 1000-10 | Taht-el-kale | Neigh | 826 | Y | 1,433 | 63% | 36% | TEK | ||

| 1000-11 | Chrysaliniotissa | Neigh | 124 | Y | 901 | 96% | 3% | Ch | ||

| 1000-12 | Ayios Kassianos (Kafesli) | Neigh | 82 | P | P | 1,177 | 90% | 10% | AKs | |

| 1000-13 | Kaimakli | Neigh | 11,564 | P | Un | 3,671 | 98% | 2% | ||

| 1000-14 | Panayia[90] | Neigh | 12,398 | Y | 2,368 | 98% | 2% | |||

| 1000-15 | St. Constantine & Helen[90] | Neigh | 3,209 | Y | ||||||

| 1000-16 | Ayioi Omoloyites | Neigh | 10,528 | Y | 1,810 | 93% | 1% | |||

| 1000-17 | Arab Ahmet | Neigh | 50 | P | S | 2,617 | 22% | 32% | AA[91] | |

| 1000-18 | Yeni Jami | Neigh | 215 | P | S | 2,345 | 28% | 72% | YJ | |

| 1000-19 | Omorfita | Neigh | 284 | P | P | 2,231 | 55% | 45% | ||

| 1000-20 | Ibrahim Pasha[70][92] | Neigh | Y | 2,334 | 28% | 66% | IP | |||

| 1000-21 | Mahmut Pasha | Neigh | 314[89] | Y | 875 | 7% | 82% | MP | ||

| 1000-22 | Abu Kavouk | Neigh | 793[89] | Y | 1,202 | 9% | 91% | AK (North) | ||

| 1000-23 | St. Luke | Neigh | 489[89] | Y | 806 | 33% | 67% | AL | ||

| 1000-24 | Abdi Chavush | Neigh | 568[89] | Y | 902 | 8% | 89% | AC | ||

| 1000-25 | Iplik Bazar & Korkut Effendi | Neigh | 229[89] | Y | 556 | 21% | 42% | IPKE | ||

| 1000-26 | Ayia Sophia | Neigh | 878[89] | P | P | 1,936 | 33% | 64% | ASo | |

| 1000-27 | Haydar Pasha | Neigh | 155[89] | Y | 385 | 12% | 87% | HP | ||

| 1000-28 | Karamanzade | Neigh | P | P | 597 | 21% | 10% | KZ | ||

| 1000-29 | Neapoli[70][92] | Neigh | Y | IP | ||||||

| 1010 | Ayios Dometios | Mun | 12,456 | P | P | 2,532 | 95% | 5% | ||

| 1011 | Engomi | Mun | 18,010 | Y | 1,396 | 100% | 0% | |||

| 1012 | Strovolos | Mun | 67,904 | Y | 3,214 | 98% | 2% | |||

| 1013 | Aglandjia | Mun | 20,783 | P | Un | 2,008 | 93% | 7% | ||

| 1014 | Ortakeuy | Vill | Y[93] | 477 | 12% | 88% | ||||

| 1015 | Trachonas | Vill | M[94] | 690 | 95% | 5% | ||||

| 1021 | Lakatameia | Mun | 3,8345 | Y | 1,537 | 94% | 6% | |||

| 1022 | Anthoupolis[95] | Set | 1,756 | Y | ||||||

| 1023 | Latsia | Mun | 16,774 | Y | 179 | 100% | 0% | |||

| 1024 | Yeri | Mun | 8,235 | P | Un | 655 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 1031 | Mia Milia | Vill | Y | 772 | 100% | 0% | ||||

| 1032 | Hamit Mandres | Vill | 2,823 | Y | 361 | 0% | 100% | |||

| 1251 | Geunyeli | Mun | 11,964 | Ind | 814 | 0% | 100% | |||

|

Code: census code. | ||||||||||

Culture

Museums

The Cyprus Archaeological Museum in Nicosia is the biggest archaeological museum in the country. It is home to the richest and largest collection of Cypriot antiques in the world. These consist exclusively of objects discovered on the island. The exhibits have been stored in the same building outside the city walls of Nicosia ever since the establishment of the museum in 1882 by the British administration reigning the island at that time.

The Ethnographic Museum of Cyprus hosts the largest collection of ethnographic artifacts in the country which includes costumes, pottery, lace, metalwork, woodcarving and paintings.

In old Nicosia, the Ethnological Museum (Hadjigeorgakis Kornesios Mansion) is the most important example of urban architecture of the last century of Ottoman domination which survives in old Nicosia. Today, the mansion which was awarded the Europa Nostra prize for its exemplary renovation work, functions as a museum where a collection of artifacts from the Byzantine, Medieval and Ottoman era are displayed.

Other museums in Nicosia include the Cyprus Museum of Natural History.

Performing arts

Nicosia offers a wide variety of musical and theatrical events, organized either by the municipality or independent organizations. The Cyprus Symphony Orchestra, established in 1987, is based in Nicosia. The orchestra, whose main sponsor is the Cyprus government, presents symphonic performances for audiences of all ages, promoting knowledge and cultivating appreciation for classical music. In addition to symphonic concerts the CySO actively engages in educational and outreach programmes, as well as other cultural activities all over Cyprus.[96] Its artistic director and chief conductor is Maestro Alkis Baltas.[97] THOC (Theatrical Organization of Cyprus) was founded in 1971 and is a member of the European Theatre Convention. It hosts a wide variety of theatre shows on a regular basis at the Latsia Municipal Theatre, Nea Skini and Theatro Ena. Skali Aglantzias is a multifunctional space in the Scali area of Aglantzia. It is made up of an open air square, amphitheatre, exhibition space, restaurant & bar. It hosts many shows, concerts and cultural events. The Satirical Theatre of Cyprus was founded in October 1983 by actor and director Vladimiros Kafkaridis. It is the first Free Theatre to be supported financially by the government. It is also the only drama school in Cyprus. Strovolos Municipal Theatre is located in the municipality's main avenue. It has hosted many charitable, cultural and educational events, as well as theatre shows, concerts, operas and ballets. Cultural events are also hosted by the Ammochostos Gate Cultural Centre, the Municipal Arts Centre, the Municipal Centre of Contemporary Social and Cultural Services and others. In June 2011, Nicosia launched its campaign to become the European Capital of Culture for 2017.[98]

Education

Nicosia has a large student community as it is the seat of eight universities, the University of Cyprus (UCY), the University of Nicosia, the European University Cyprus, the Open University of Cyprus, Frederick University, Near East University, the University of Mediterranean Karpasia and Cyprus International University.

Economy

Nicosia is the financial and business heart of Cyprus. The city hosts the headquarters of all Cypriot banks namely Cyprus Popular Bank (also known as Laiki Bank), Bank of Cyprus, the Hellenic Bank. Further, the Central Bank of Cyprus is located in the Acropolis area of the Cypriot capital.

A number of international businesses base their Cypriot headquarters in Nicosia, such as the big four audit firms PWC, Deloitte, KPMG and Ernst & Young. International technology companies such as NCR and TSYS have their regional headquarters in Nicosia. The city is also home to local financial newspapers such as the Financial Mirror and Stockwatch.

Cyprus Airways has its head offices in the entrance of Makariou Avenue.[99]

According to a recent UBS survey in August 2011, Nicosia is the wealthiest per capita city of the Eastern Mediterranean and the tenth richest city in the world by purchasing power in 2011.[100]

Climate

Nicosia has a subtropical-hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh)[101] with long, hot and dry summers. Most of the rainfall occurs in winter.

| Climate data for Athalassa, Nicosia, elevation: 162 m (Satellite view) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

33.9 (93) |

36.9 (98.4) |

36.7 (98.1) |

33.6 (92.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

26 (79) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

22.2 (72) |

27.2 (81) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.0 (86) |

27.1 (80.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

20.0 (68) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.2 (73.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.2 (54) |

6.8 (44.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 54.7 (2.154) |

41.6 (1.638) |

28.3 (1.114) |

19.9 (0.783) |

23.5 (0.925) |

17.6 (0.693) |

5.80 (0.2283) |

1.30 (0.0512) |

11.7 (0.461) |

17.4 (0.685) |

54.6 (2.15) |

65.8 (2.591) |

342.2 (13.472) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 7.3 | 6.5 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 7.7 | 43.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 182.9 | 200.1 | 238.7 | 267.0 | 331.7 | 369.0 | 387.5 | 365.8 | 312.0 | 275.9 | 213.0 | 170.5 | 3,314.1 |

| Source: Meteorological Service (Cyprus)[102] | |||||||||||||

Another chart with cooler temperatures.[103]

| Climate data for Nicosia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

16 (61) |

18.7 (65.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

28.6 (83.5) |

33 (91) |

35.9 (96.6) |

36 (97) |

32.6 (90.7) |

27.8 (82) |

22.2 (72) |

17 (63) |

25.53 (78) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

21.1 (70) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

25 (77) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.1 (61) |

11.9 (53.4) |

18.82 (65.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5 (41) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

14 (57) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

12.16 (53.88) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 60 (2.36) |

45 (1.77) |

39 (1.54) |

20 (0.79) |

18 (0.71) |

5 (0.2) |

1 (0.04) |

2 (0.08) |

7 (0.28) |

27 (1.06) |

34 (1.34) |

71 (2.8) |

329 (12.97) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org, altitude: 149m[103] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Transportation

Nicosia is linked with other major cities in Cyprus via a modern motorway network. The A1 connects Nicosia with Limassol in the south with the A6 going from Limassol onto Paphos. The A2 links Nicosia with the south eastern city of Larnaca with the A3 going from Larnaca to Ayia Napa. The A9 connects Nicosia to the west Nicosia district villages and the Troodos mountains.

Public transport within the city is currently served by a new and reliable bus service. Bus services in Nicosia are run by OSEL.[104] In the northern part, the company of LETTAŞ provides this service.[105] Many taxi companies operate in Nicosia. Fares are regulated by law and taxi drivers are obliged to use a taximeter.

In 2010, as part of the Nicosia Integrated Mobility Plan, a pre-feasibility study for a proposed tram network has taken place and sponsored by the Ministry of Communications and Works. The study compared two scenarios, with and without the operation of a tramway in terms of emitted polluting loads. The study realised that the reduction in the pollutants per transported passenger for the scenario with tramway, fluctuates from 5–10% and reaches up to 90% specifically in the central roads of Nicosia.[106]

In 2011, the Nicosia Municipality introduced the Bike in Action scheme, a bicycle sharing system which covers the Greater Nicosia area. The scheme is run by the Inter-Municipal Bicycle Company of Nicosia (DEPL).[107] While the bike-lane network is being upgraded, the scheme aims to serve a large portion of the population, university students and tourist groups in their movement to and from downtown. The scheme has 27 docking stations spread across seven municipalities and involves 315 bikes which people can borrow from any designated station and return to any other station of their choosing. Specifically the Nicosia Municipality has installed 100 bikes in 5 stations, the Aglandjia Municipality 50 bikes at 4 stations, the Municipality of Strovolos 80 bikes at 8 stations, the Municipality of Dali 20 cycles at 3 stations, the Municipality of Ayios Dhometios 20 cycles at 2 stations, the Municipality of Latsia 15 bikes at 2 station and the Municipality of Engomi 30 cycles at 3 stations. People do not have to register to use the bikes as long as they have a credit or debit card in order to pay a €150 security deposit. The deposit is paid back within 24 hours of returning the bike.[108][109]

There is currently no train network in Cyprus however plans for the creation of an intercity railway are currently under way. The first railway line on the island was the Cyprus Government Railway which operated from 1905 to 1951. There were 39 stations, stops and halts, the most prominent of which served Famagusta, Prastio Mesaoria, Angastina, Trachoni, Nicosia, Kokkinotrimithia, Morphou, Kalo Chorio and Evrychou. It was closed down due to financial reasons.[110]

Mayors of Nicosia

Pre-Independence (1882–1959)

- Christodoulos Severis, 15 November 1882 – 31 July 1888.

- Achilleas Liassides, 1 August 1888 – 10 April 1906.

- Antonios Theodotou, 8 January 1888 – 10 April 1906.

- Mehmet Şevket Bey, 11 April 1908 – 31 March 1911.

- Antonios Theodotou, 1924–1926

- George Markides, 6 April 1926 – 31 March 1929.

- Themistoclis Dervis, 5 April 1929 – 28 September 1946.

- Ioannis Clerides, 1 June 1946 – 31 May 1949 (Last elected Mayor until 1986).

- Themistoclis Dervis, 1 June 1949 – 18 December 1959.

Post-Independence (1959–1974)

- Diomedes Skettos, 1959–1960.

- George M. Spanos, 1960–1962; 1963–1964.

- Odysseas Ioannides, 1964–1970.

- Lellos Demetriades, December 1971 – July 1974 (dismissed by the July 15 Coup).

After 1974

- Christoforos Kithreotis, August 1974.

- Lellos Demetriades, October 1974 – 2001 (Elected in 1986; reelected in 1991 and 1996).

- Michalis Zampelas, 2002–2006.

- Eleni Mavrou, 2007–2011.

- Constantinos Yiorkadjis, 2011–present.

Sports

Football

Football is the most popular sport in Cyprus, and Nicosia is home of three major teams of the island; APOEL, Omonia and Olympiakos. APOEL and Omonia dominate Cypriot football. There are also many other football clubs in Nicosia and the suburbs. Nicosia is also home to Ararat FC, the island's only Armenian FC.

Other sports

Nicosia is also the home for many clubs for basketball, handball and other sports. APOEL and Omonia have basketball and volleyball sections and Keravnos is one of the major basketball teams of the island. The Gymnastic Club Pancypria (GSP), the owner of the Neo GSP Stadium, is one of the major athletics clubs of the island. Also, all teams in the Futsal First Division are from Nicosia.

Venues

Nicosia has some of the biggest venues in the island; The Neo GSP Stadium, the biggest in Cyprus, with capacity of 23,400 is the home for the national team, APOEL, Olympiakos and Omonia. The other big football stadium in Nicosia is Makario Stadium with capacity of 16,000. The Eleftheria Indoor Hall is the biggest basketball stadium in Cyprus, with capacity of 6,500 seats and is the home for the national team, APOEL and Omonia. The Lefkotheo indoor arena is the volleyball stadium for APOEL and Omonia.

International and European events

Nicosia hosted the 2000 ISSF World Cup Final shooting events for the shotgun. Also the city hosted two basketball events; the European Saporta Cup in 1997 and the 2005 FIBA Europe All Star Game in the Eleftheria Indoor Hall. Another event which was hosted in Nicosia were the Games of the Small States of Europe in 1989 and 2009.

Famous Nicosians

- Glafkos Klerides, president of the Republic of Cyprus (1993–2003).

- Kıbrıslı Mehmed Kamil Pasha, Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire.

- Fazıl Küçük, former vice president of the Republic of Cyprus (1960–1963).

- Marios Garoyian, former President of the House of Representatives Republic of Cyprus (2008–2011), President of Democratic Party since 2006.

- Michalis Hatzigiannis, singer.

- Manoug Parikian,(1920–1987), a top-ranking world-class concert violinist and violin professor in the United Kingdom, with numerous concerts and recordings

- Peter I of Cyprus, King of Cyprus.

- Benon Sevan, Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations (1992–2005) and the Head of the Oil for Food program (1996–2005)

- Diam's, French rap singer.

- Hazar Erguclu, actress on the Turkish drama, Medcezir.

- Christopher A. Pissarides, Nobel Prize winner in Economics.

- Suat Günsel, entrepreneur, businessman and founder of the Near East University.

- Kutlu Adali, journalist, poet and socio-political researcher and peace advocate.

- Mustafa Djamgoz, professor of cancer biology at Imperial College London and chairman of the College of Medicine’s Science Council.

- Neoklis Kyriazis, historian and member of the National Council of Cyprus.

- Nicos Tornaritis, politician and jurist, member of the Cyprus Parliament and Consultant of the Republic of Kenya

- Constandinos Yiorkadjis, Mayor of Nicosia since December of 2011

- Tassos Papadopoulos, President of the Republic of Cyprus (2003–2008)

- Mick Karn (Andonis Michaelides), musician, bassist of the art rock/New Wave band Japan (1974–1982)

International relations

Twin towns and Sister cities

Twinnings[111]

Collaborations[111]

Gallery

-

View of Central Business Destrict from Solomos Square.

-

Makariou Avenue

-

Faneromeni School façade, Faneromeni Square

-

Old mansions in Nicosia old city

-

Saint Antonios food market

-

National Bank of Greece Building – Lyssiotis Mansion in Makariou Avenue

-

Historical mansions in Nicosia old city

-

Nicosia skyline view from old part of city

-

Old quarter in Nicosia city center with Medieval architecture

-

House in old part of the city

-

-

Themistokli Dervi Avnue

-

Downtown Nicosia

-

Nicosia fruit market

-

Interior of the "Mall of Cyprus"

-

Nicosia Theatre House

-

Venetian historic ancient walls

-

Makariou Avenue during the afternoon

-

Kykkos Monastery exterior

-

Kykkos Monastery interior

-

Ledra Street during Christmas

-

Faneromeni church

See also

References

- ↑ Farid Mirbagheri (1 October 2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6298-2. "But the international community did not recognise the changes brought about by the use of force and continued to acknowledge the Government of Cyprus, run by Greek Cypriots, as the only legal representation of the state of Cyprus."

- ↑ John Van Oudenaren (2005). Uniting Europe: An Introduction to the European Union. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 352–. ISBN 978-0-7425-3661-6. "The northern part of the island declared itself to be an independent state, which the international community does not recognise."

- ↑ Max Hilaire (1 January 2005). United Nations Law and the Security Council. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-7546-4489-7. "The international community continues to recognise the Greek Cypriot Government based in Nicosia as the legitimate ..."

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. (1 March 2010). Britannica Book of the Year 2010. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. pp. 558–. ISBN 978-1-61535-366-8. "...the Republic of Cyprus (ROC), predominantly Greek in character, occupying the southern two-thirds of the island, which is the original and still the internationally recognised de jure government of the whole island,"

- ↑ Marise Cremona (2008). Developments in EU External Relations Law. Oxford University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-19-955289-4. "The EU had to take account of the situation that the Republic of Cyprus is the only dejure recognised State on the island,"

- ↑ Susannah Verney (13 September 2013). EUROSCEPTICISM IN SOUTHERN EUROPE. Routledge. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-1-317-99612-5. "The international community (UN, EU, Council of Europe and other international organisations) recognise the de jure sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus over the whole island."

- ↑ Thomas Diez (2002). The European Union and the Cyprus Conflict: Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union. Manchester University Press. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-0-7190-6079-3. "In other words, it is only the Republic of Cyprus that is internationally recognised, and so the Greek-Cypriot government has been also accepted as the de jure government of the island as a whole,..."

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Population Enumerated by Sex, Age, District, Municipality/Community and Quarter, 2011 – (2011 Census of the Republic of Cyprus, Statistical Service)" (in (Greek)). Mof.gov.cy. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "TRNC General Population and Housing Unit Census – (TRNC State Planning Organisation)" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ Derya Oktay, "Cyprus: The South and the North", in Ronald van Kempen, Marcel Vermeulen, Ad Baan, Urban Issues and Urban Policies in the new EU Countries, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005, ISBN 978-0-7546-4511-5, p. 207.

- ↑ Wolf, Sonia (26 October 2009). "20 years after Berlin Wall fell, Nicosia remains divided". Google news (AFP). Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ↑ Phoebe Koundouri, Water Resources Allocation: Policy and Socioeconomic Issues in Cyprus. Springer, 2010, ISBN 9789048198245, p. 69.

- ↑ "World's richest cities by purchasing power". City Mayors. 2011-08-18. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Follow the mail on Twitter. (2011-05-24). "Trees fall ahead of Eleftheria project". Cyprus-mail.com. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "The First Move". Time Magazine. 27 August 1956. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ "War and Politics-Cyprus". Britains-smallwars.com. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Keshishian, Kevork K. (1978). Nicosia: Capital of Cyprus Then and Now, p. 78-83, The Mouflon Book and Art Centre.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Saint Tryphillius". Saintsoftheday108.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "The Crusades – home page". Boisestate.edu. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Nicosia" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Cyprus – Historical Setting – Ottoman Rule". Historymedren.about.com. 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 A description of the historic monuments of Cyprus. Studies in the archaeology and architecture of the island, by George Jeffery, Architect, 1918

- ↑ "Nicosia". Conflictincities.org. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Coexistence in the Disappeared Mixed Neighbourhoods of Nicosia, by Ahmet An (Paper read at the conference, “Nicosia: The Last Divided Capital in Europe”, organized by the London Metropolitan University on 20th June 2011)

- ↑

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ See map drawn in 1952 published in "Romantic Cyprus", by Kevork Keshishian, 1958 edition

- ↑ "Levkosia, the capital of Cyprus" by Archduke Louis Salvator, 1881

- ↑ Municipality web site: http://www.nicosia.org.cy retrieved Aug 2013, section on Municipal Building

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Order No. 397 published in Cyprus Gazette No. 1597, 4th August 1923

- ↑ Nicosia Capital of Cyprus by Kevork Keshishian, pub 1978

- ↑ "EOKA (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston)". Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ↑ "War and Politics – Cyprus". Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ↑ Solsten, Eric. "The Republic of Cyprus". US Library of Congress. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Solsten, Eric. "Intercommunal Violence". US Library of Congress. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ "CYPRUS: Big Troubles over a Small Island". TIME. 29 July 1974.

- ↑ "Nicosia Municipality". Nicosia.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ The Cyprus Conspiracy: America, Espionage and the Turkish Invasion. By Brendan O'Malley, Ian Craig. Books.google.com. 2001-08-25. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Malcolm Nathan Shaw, International Law, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-82473-6, p. 212.

- ↑ "Emotion as Cyprus border opens". BBC News. 2003-04-23. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Operation in Cyprus". Docs.google.com. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Symbolic Cyprus crossing reopens". BBC News. 2008-04-03. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Full list UN Resolutions on Cyprus". Un.int. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ See official web site of the Nicosia Water Board, http://www.wbn.org.cy (extract 20/5/13)

- ↑ See official web site of the Nicosia Sewerage Board, http://www.sbn.org.cy/ (extract 20/5/13)

- ↑ See the official web site of Organisation for Communications of Nicosia District. , http://www.osel.com.cy

- ↑ e.g. Constitution of Cyprus Article 153, s2 - "The seat of the High Court shall be in the capital of the Republic."

- ↑ Constitution of Cyprus Article 173 - "Separate municipalities shall be created in the five largest towns of the Republic, that is to say, Nicosia, Limassol, Famagusta, Larnaca and Paphos by the Turkish inhabitants thereof"

- ↑ Law 1959 c3

- ↑ Phoebe Koundouri, Water Resources Allocation: Policy and Socioeconomic Issues in Cyprus, p. 70.

- ↑ Phoebe Koundouri, Water Resources Allocation: Policy and Socioeconomic Issues in Cyprus, Springer, 2010, p. 70.

- ↑ The Middle East: a survey and directory of the countries of the Middle East, Europa Publications., 1966, p. 171.

- ↑ "The Constitution – Appendix D: Part 12 – Miscellaneous Provisions" (in (Greek)). Cyprus.gov.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "The Issue of Separate Municipalities and the Birth of the New Republic: Cyprus 1957–1963 (University of Minnesota Press, 2000)". Cyprus-conflict.net. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "The Library of Congress – Country Studies: Cyprus – Ch. 4 – 1960 Constitution". Lcweb2.loc.gov. 2010-07-27. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Reddick, Christopher G. Comparative E-Government. ISBN 1-4419-6535-1.

- ↑ Official web site of Engomi municipality, history section (Greek version), http://www.engomi.org.cy

- ↑ Census of Cyprus (available from Statistical Service, Nicosia). Document: Population - Place of Residence, 2011, Table C. Municipality/Community, Quarter and Street Index published by Ministry of Information (CILIS_streets_022011)

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Official Gazette of the Republic No. 4341 and dated 25.01.2010

- ↑ Official web site of Nicosia municipality http://www.nicosia.org.cy and http://www.scribd.com/doc/Οι-ενορίες-της-Λευκωσίας

- ↑ Official web site of Strovolos municipality, history section (English version), http://www.strovolos.org.cy

- ↑ Official web site of Lakatamia municipality, history section (English version), http://www.lakatamia.org.cy

- ↑ Official web site of Latsia municipality, history section (English version), http://www.latsia.org.cy

- ↑ Official web site of municipality http://www.aglantzia.com/english

- ↑ Municipal web site, August 2013: www.gonyeli.org/

- ↑ The authority has the population, economic viability and consent of the (original) inhabitants prescribed in the Municipalities Law (see Law 11/1985), without having been formally recognised as a municipality under that law. See also www.prio-cyprus-displacement.net/default_print.asp?id=300 retrieved August 2013

- ↑ See Municipal web site and postcode publication tk cyp Posta Kodları.pdf (May 2013)

- ↑ http://www.prio-cyprus-displacement.net/default.asp?id=301

- ↑ http://www.lefkosabelediyesi.org/english/news/cln_hamitkoy.htm (retrieved Aug 2013)

- ↑ http://www.lefkosaturkbelediyesi.org/turkce/muhtarlar.htm retrieved Aug 2013

- ↑ http://www.prio-cyprus-displacement.net/default.asp?id=342

- ↑ http://www.prio-cyprus-displacement.net/default.asp?id=332 (Aug 2013)

- ↑ http://www.miamilia.coop.com.cy (retrieved Aug 2013)

- ↑ http://www.lefkosaturkbelediyesi.org/turkce/muhtarlar.htm

- ↑ http://www.prio-cyprus-displacement.net/default.asp?id=362

- ↑ Nicosia Turkish Municipality treats it as four neighbourhoods, see www.lefkosaturkbelediyesi.org/turkce/muhtarlar.htm

- ↑ 6th edition of the publication “Statistical Codes of Municipalities, Communities and Quarters of Cyprus” (publ. Statistical Service of Republic of Cyprus); Census of Cyprus 1946; List of Mahalla Mukhtars publ.by Nicosia Turkish Municipality

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 89.3 89.4 89.5 89.6 89.7 Census organised by the Turkish Cypriots in the occupied area http://www.devplan.org/Nufus-2011/nufus%20ikinci_.pdf retrieved October 2013

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Pallouriotissa was split into Panaya and St. Constantine & Helen after 1968 .

- ↑ Keushk Chiftlik (Kösklüçiftlik) is the area outside of the walls in Nicosia Turkish Municiplity

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 The neighborhood of Neapoli was separated from the neighborhood of Ibrahim Pasha 25 Jan 2010.

- ↑ Small part in Göçmenköy neighbourhood

- ↑ Divided into 4 new neighbourhoods

- ↑ The settlement of Anthoupolis is an enclave created within the municipality of Lakatameia after 1974.

- ↑ "Cyprus Symphony Orchestra". Cyso.org.cy. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ Cyprus Symphony Orchestra. "Cyprus Symphony Orchestra". Cyso.org.cy. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Nicosia-Cyprus presents candidacy for European Cultural Capital". Citiesintransition.posterous.com. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Addresses Cyprus Airways

- ↑ "The most expensive and richest cities in the world – A report by UBS". Citymayors.com. 2011-08-18. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ Map

- ↑ "Meteorological Service – Climatological and Meteorological Reports". August 2011.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 "Climate: Nicosia - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ "Οργανισμός Συγκοινωνιών Επαρχίας Λευκωσίας". Osel.com.cy. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "Kurban bayramı yarın başlıyor". Star Kıbrıs. 19 December 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ↑ (Greek) http://www.mcw.gov.cy/mcw/mcw.nsf/All/07E87A85E80AD127C225781C0043861D/$file/IMMP%20Final%20Report%20Appendices.pdf

- ↑ "Ποδηλατο Εν Δρασει / Home". Podilatoendrasi.com.cy. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ Cyprus Mail – October 27, 2011 – Bike sharing scheme launched

- ↑ "Bike In Action website". Podilatoendrasi.com.cy. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ↑ "Study underway for Cyprus railway network". Famagusta Gazette. 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2012-06-13.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 http://www.nicosia.org.cy/english/lefkosia_twins.shtm Nicosia twinnings

- Nicosia Municipality (south) website

- Nicosia Municipality (north) website

- Nicosia Municipality website – Transportation

- Cyprus Island – Nicosia

- The World of Cyprus bilingual information portal with background on folk culture and Byzantine influences

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nicosia. |

- English-language website for Municipality of Nicosia (Λευκωσια)

Nicosia travel guide from Wikivoyage

Nicosia travel guide from Wikivoyage- "Nicosia in Dark and White" A photo project about the city's old abandoned buildings

- Organisational structure of Islamic religion in Cyprus

- Echoes Across the Divide (2008) is a documentary film about an attempt to bridge the Green Line with a bicommunal music project performed from the rooftops of Old Nicosia

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||