Nicolas Steno

| Blessed Nicolas Steno | |

|---|---|

| Vicar Apostolic of Nordic Missions | |

Portrait of Steno as bishop | |

| See | Titopolis |

| Appointed |

21 August 1677 by Pope Innocent XI |

| Term ended | 5 December 1686 |

| Predecessor | Valerio Maccioni |

| Successor | Friedrich von Tietzen[notes 1] |

| Other posts | Titular Bishop of Titopolis |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 13 April 1675[2] |

| Consecration |

19 September 1677 by Saint Gregorio Barbarigo[3][4] |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Niels Stensen |

| Born |

1 January 1638 [NS: 11 January 1638] Copenhagen, Denmark-Norway |

| Died |

25 November 1686 (aged 48) [NS: 5 December 1686] Schwerin, Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

| Buried | Basilica of San Lorenzo, Italy |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Parents | |

| Occupation |

|

| Previous post |

|

| Coat of arms |

|

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 5 December |

| Venerated in | 1686 |

| Beatified |

23 October 1988 Rome, Vatican City by Pope John Paul II |

Nicolas Steno (1 January 1638 – 25 November 1686[7][8] [NS: 11 January 1638 – 5 December 1686][7]) was a Danish Catholic bishop and scientist and a pioneer in both anatomy and geology. Steno was trained in the classical texts on science; however, by 1659 he seriously questioned accepted knowledge of the natural world.[9] Importantly he questioned explanations for tear production, the idea that fossils grew in the ground and explanations of rock formation. His investigations and his subsequent conclusions on fossils and rock formation have led scholars to consider him one of the founders of modern stratigraphy and modern geology.[10][11]

Born to a Lutheran family, Steno converted to Catholicism in 1667. After his conversion, his interest for natural sciences rapidly waned giving way to his interest in theology.[12] At the beginning of 1675, he decided to become a priest. Four months after, he was ordained in the Catholic clergy in Easter 1675. As a clergyman, he was later appointed by Pope Innocent XI Vicar Apostolic of Nordic Missions and Titular Bishop of Titopolis. Steno played an active role in the Counter-Reformation in Northern Germany. He was venerated as a saint after his death and the Roman Catholic canonization process was begun in 1938. Pope John Paul II beatified Steno in 1988.[13]

Early life and career

Nicolas Steno (Danish: Niels Stensen; Latinized to Nicolaus Stenonis or Nicolaus Stenonius[notes 2]) was born in Copenhagen on New Year's Day 1638 (Julian calendar), the son of a Lutheran goldsmith who worked regularly for King Christian IV of Denmark. Suffering from an unknown disease, he grew up in isolation during his childhood. In 1644 his father died, after which his mother married another goldsmith. In 1654–1655, 240 pupils of his school died because of the plague. Across the street lived Peder Schumacher (who would offer Steno a post as professor in Copenhagen in 1671). At the age of 19, Steno entered the University of Copenhagen to pursue medical studies.[14] After completing his university education, Steno set out to travel through Europe; in fact, he would be on the move for the rest of his life. In the Netherlands, France, Italy and Germany he came into contact with prominent physicians and scientists. These influences led him to use his own powers of observation to make important scientific discoveries. At a time when scientific questions were mostly answered by appeal to ancient authorities, Steno was bold enough to trust his own eyes, even when his observations differed from traditional doctrines.

At the urging of Thomas Bartholin, Steno first travelled to Rostock, then to Amsterdam, where he studied anatomy under and lodged at Gerard Blasius, focusing on the Lymphatic system. Within a few months Steno moved to Leiden, where he met the students Jan Swammerdam, Frederik Ruysch, Reinier de Graaf, Franciscus de le Boe Sylvius, a famous professor, and Baruch Spinoza.[15] At the time Descartes was publishing on the working of the brain, and Steno did not think his explanation of the origin of tears[16] produced by the brain was correct. He travelled to Paris where he was invited by Henri Louis Habert de Montmor and Pierre Bourdelot, and met Ole Borch and Melchisédech Thévenot who were all interested in new research and demonstrations of his skills. In 1665 Stensen travelled to Saumur, Bordeaux and Montpellier, where he met Martin Lister and William Croone, who introduced Steno's work to the Royal Society.

After travelling through France, he settled in Italy in 1666. At first as professor of anatomy at the University of Padua and then in Florence as in-house physician of Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando II de' Medici, who supported arts and science and whom Steno had met in Pisa.[17] Steno was invited to live in the Palazzo Vecchio, in return he had to gather a Cabinet of curiosities. Steno went to Rome and met Pope Alexander VII and Marcello Malpighi, who he admired. On his way back he watched a Corpu Christi procession in Livorno and wondered if he had the right belief.[18] In Florence Steno focused on the muscular system and the nature of muscle contraction. He became a member of Accademia del Cimento and had long discussions with Francesco Redi. Like Vincenzo Viviani, Steno proposed a geometrical model of muscles to show that a contracting muscle changes its shape but not its volume.[19][20]

Scientific contributions

Anatomy

During his stay in Amsterdam, Steno discovered a previously undescribed structure, the "ductus stenonianus" (the duct of the parotid salivary gland) in sheep, dog and rabbit heads. A dispute with Blasius over credit for the discovery arose, but Steno's name remained associated with this structure known today as the Stensen's duct.[21] In Leiden, Steno studied the boiled heart of a cow, and determined that it was an ordinary muscle[22][23] and not the center of warmth as Galenus and Descartes believed.[24]

Paleontology

In October 1666 two fishermen caught a huge female shark near the town of Livorno, and Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, ordered its head to be sent to Steno. Steno dissected the head and published his findings in 1667. He noted that the shark's teeth bore a striking resemblance to certain stony objects, found embedded within rock formations, that his learned contemporaries were calling glossopetrae or "tongue stones". Ancient authorities, such as the Roman author Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia, had suggested that these stones fell from the sky or from the Moon. Others were of the opinion, also following ancient authors, that fossils naturally grew in the rocks. Steno's contemporary Athanasius Kircher, for example, attributed fossils to a "lapidifying virtue diffused through the whole body of the geocosm", considered an inherent characteristic of the earth – an Aristotelian approach. Fabio Colonna, however, had already shown in a convincing way that glossopetrae are shark teeth,[25] in his treatise De glossopetris dissertatio published in 1616.[26] Steno added to Colonna's theory a discussion on the differences in composition between glossopetrae and living sharks' teeth, arguing that the chemical composition of fossils could be altered without changing their form, using the contemporary corpuscular theory of matter.

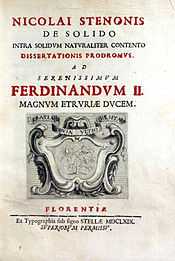

Steno's work on shark teeth led him to the question of how any solid object could come to be found inside another solid object, such as a rock or a layer of rock. The "solid bodies within solids" that attracted Steno's interest included not only fossils, as we would define them today, but minerals, crystals, encrustations, veins, and even entire rock layers or strata. He published his geologic studies in De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento dissertationis prodromus, or Preliminary discourse to a dissertation on a solid body naturally contained within a solid in 1669. This book was his last scientific work of note.[27][notes 3] Steno was not the first to identify fossils as being from living organisms; his contemporaries Robert Hooke and John Ray also argued that fossils were the remains of once-living organisms.

Geology and stratigraphy

Steno, in his Dissertationis prodromus of 1669 is credited with three of the defining principles of the science of stratigraphy: the law of superposition: "... at the time when any given stratum was being formed, all the matter resting upon it was fluid, and, therefore, at the time when the lower stratum was being formed, none of the upper strata existed"; the principle of original horizontality: "Strata either perpendicular to the horizon or inclined to the horizon were at one time parallel to the horizon"; the principle of lateral continuity: "Material forming any stratum were continuous over the surface of the Earth unless some other solid bodies stood in the way"; and the principle of cross-cutting relationships: "If a body or discontinuity cuts across a stratum, it must have formed after that stratum."[28] These principles were applied and extended in 1772 by Jean-Baptiste L. Romé de l'Isle. Steno's ideas still form the basis of stratigraphy and were key in the development of James Hutton's theory of infinitely repeating cycles of seabed deposition, uplifting, erosion, and submersion.[28]

Steno's landmark theory that the fossil record was a chronology of different living creatures in different eras was a sine qua non for Darwin's theory of natural selection.

Crystallography

Steno gave the first accurate observations on a type of crystal in his 1669 book "De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento".[29] The principle in crystallography, known simply as Steno's law, or Steno's law of constant angles or the First Law of Crystallography [30], states that the angles between corresponding faces on crystals are the same for all specimens of the same mineral. Steno's seminal work paved the way for the law of the rationality of the crystallographic indices of French mineralogist René-Just Haüy in 1801.[29][31] This fundamental breakthrough formed the basis of all subsequent inquiries into crystal structure.

Religious studies

Steno's questioning mind also influenced his religious views. Having been brought up in the Lutheran faith, he nevertheless questioned its teachings, something which became a burning issue when confronted with Roman Catholicism while studying in Florence. After making comparative theological studies, including reading the Church Fathers and by using his natural observational skills, he decided that Catholicism, rather than Lutheranism, provided more sustenance for his constant inquisitiveness. In 1667, Steno converted to Catholicism on All Souls' Day when Lavinia Cenami Arnolfini, a noblewoman of Lucca, insisted.[32][33]

Steno traveled to Hungary, Austria and in Spring 1670 he arrived in Amsterdam. There he met with old friends Jan Swammerdam and Reinier de Graaf. With Anna Maria van Schurman and Antoinette Bourignon he discussed scientific and religious topics. The following quote is from a 1673 speech:

- Fair is what we see, Fairer what we have perceived, Fairest what is still in veil.[34]

It is not clear if he met Nicolaes Witsen, but he did read Witsen's book on shipbuilding. In 1671 he accepted the post of professor of anatomy in the University of Copenhagen,[17] but promised Cosimo III de' Medici he would return when he was appointed tutor to Ferdinando III de' Medici.

At the beginning of 1675, Steno decided to continue his theological studies, which he had begun even before his conversion, toward his ordination to the priesthood.[35] After only 4 months, he was ordained priest and celebrated his first mass on 13 April 1675 in the Basilica of the Santissima Annunziata in Florence at the age of 37.[36][32][35] Athanasius Kircher expressly asked what were the reasons why he decided to become priest.[35] Steno had left natural sciences for education and theology and became one of the leading figures in the Counter-Reformation.[27] Upon request of Duke Johann Friedrich of Hanover, Pope Innocent XI made him Vicar Apostolic for the Nordic Missions on 21 August 1677. He was consecrated titular bishop of Titiopolis on 19 September by Cardinal Barbarigo and moved to the Lutheran North.[3]

In the year after he was made bishop, he was probably involved in the banning of publications by Spinoza,[37] There he had talks with Gottfried Leibniz, the librarian; the two argued about Spinoza and his letter to Albert Burgh, then Steno's pupil.[38] Leibniz recommended a reunification of the churches. Steno worked at the city of Hannover until 1680.

After John Frederick death's, Prince-Bishop of Paderborn Ferdinand of Fürstenberg appointed him as Auxiliary Bishop of Münster (Church Saint Liudger) on 7 October 1680.[36] The new prince-elector Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover was a Protestant. Earlier, Augustus' wife, Sophia of Hanover, had made fun of Steno's piousness; he had sold his bishop's ring and cross to help the needy.[citation needed] He continued zealously the work of counter reform begun by Bernhard von Galen.[36]

In 1683, Steno resigned as auxiliary bishop after an argument about the election of the new bishop, Maximilian Henry of Bavaria and moved in 1684 to Hamburg.[32] There Steno became involved again in the study of the brain and the nerve system with an old friend Dirck Kerckring.[39] Steno was invited to Schwerin, when it became clear he was not accepted in Hamburg. Steno dressed like a poor man in an old cloak. He drove in an open carriage in snow and rain. Living four days a week on bread and beer, he became emaciated.[notes 4] When Steno had fulfilled his mission, some years of difficult tasks, he wanted to go back to Italy. Before he could return, Steno became severely ill, his belly swelling day by day. Steno died in Germany, after much suffering. His corpse was shipped to Florence by Kerckring upon request of Cosimo III de' Medici and buried in the Basilica of San Lorenzo close to his protectors, the De' Medici family.[36] In 1946 his grave was opened,[40] and the corpse was reburied after a procession through the streets of the city.[41]

Beatification

After his death in 1686, Steno was venerated as a saint in the diocese of Hildesheim.[36] Steno's piety and virtue have been evaluated with a view to an eventual canonization. His canonization process was begun in Osnabrück in 1938.[36] In 1953 his grave in the crypt of the church of San Lorenzo was opened as part of the beatification process.[42] His corpse was transferred to a fourth-century Christian sarcophagus found in the river Arno donated by the Italian state. His remains were placed in a lateral chapel of the church that received the name of "Capella Stenoniana".[36][42] He was declared "beatus" — the third of four steps to being declared a saint — by Pope John Paul II in 1988. He is thus now called by Catholics Blessed Nicolas Steno. His feast day is 5 December.[36]

Legacy

Steno's life and work has been studied, in particular in relation to the developments in geology in the late nineteenth century.

- The Steno Museum in Aarhus, Denmark, named after Nicolas Steno, holds exhibitions on the history of science and medicine.[43] It also operates a planetarium, a medicinal herb garden and the greenhouses in Aarhus Botanical Gardens.

- Impact craters on Mars (68°00′S 115°36′W / 68.0°S 115.6°W) and the Moon are named in his honor.

- The mineral stenonite was named in his honour.[44][45]

- The Catholic parish church of Grevesmühlen, North Germany, built from 1989 to 1991, is dedicated to Nicolas Steno.[46]

- In 1950 the "Niels Steensens Gymnasium", a Catholic preparatory school, was founded by the Jesuit Order in Copenhagen.[47]

- Steno Diabetes Center, a research and teaching hospital dedicated to diabetes in Gentofte, Denmark, was named after Nicolas Steno.

- The Istituto Niels Stensen was founded in 1964 in Florence, Italy. Administered by the Jesuit Order, it is dedicated to his memory.

- On 11 January 2012, Steno was commemorated with a Google doodle.[48][49][50]

Major works

- Steensen, Niels / Sténon, Nicolas. Nicolai Stenonis Observationes anatomicae quibus varia oris, oculorum et narium vasa describuntur, novique salivae, lacrymarum et muci fontes deteguntur, et novum nobilissimi Bilsii de lymphae motu et usu commentum examinatur et rejicitur, Lugduni Batavorum: apud J. Chouet, (1662) via Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine (Paris)

- Steensen, Niels /Steno, Nicolas. Nicolai Stenonis De Musculis et glandulis observationum specimen, cum epistolis duabus anatomicis, Hafniae: lit. M. Godicchenii, (1664). via Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine (Paris)

- Nicolai Stenonis Elementorum Myologiae Specimen, seu Musculi Descriptio Geometrica, cui accedunt canis carchariae dissectum caput et dissectus piscis ex canum genere... Florentiae : ex typ. sub signo Stellae, (1667) via Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine (Paris).

- Discours de M. Stenon sur l'anatomie du cerveau..., R. de Ninville (Paris), 1669 via Gallica

- Nicolai Stenonis solido intra solidum naturaliter contento dissertationis prodromus ... Florentiae : ex typographia sub signo Stellae (1669), via Google Books The Prodromus of Nicolaus Steno's Dissertation concerning a solid body enclosed by process of nature within a solid; an English version with an introduction and explanatory notes by John Garrett Winter, New York: Macmillan Company, (1916) via Internet Archive

- Nicolai Stenonis Opera philosophica, edited by Wilhelm Maar... vol. I, Copenhagen : V. Tryde, (1910) via Gallica

- Nicolai Stenonis Opera philosophica, edited by Wilhelm Maar... vol. II, Copenhagen : V. Tryde, (1910)

References

- Notes

- ↑ Friedrich von Tietzen, called Schlüter (1626-1696)[1]

- ↑ Also known as Nikolaus or Nils Steensen, Stens.[2] Steno took his surname from his father's given name. In accordance with the academic customs of his time, Nicolas latinized the Danish form of his name Niels Ste(e)nsen as Nicolaus Stenonis. The English form, Steno, is due to an error in parsing the Latin.[3]

- ↑ Leibnitz came to know and esteem Steno in Hannover and expressed deep regrets that Steno had abandoned his earlier studies.[4]

- ↑ On the other days there were never more than four courses plus a dessert, even though noblemen from the court often dined with him.

- Citations

- ↑ Janker, Stephan M. (1990). Die Bischöfe des Heiligen Römischen Reiches : ein biographisches Lexikon (in German). Berlin: Duncker und Humblot. p. 516. ISBN 978-3-428-06763-3.

- ↑ Kermit 2002, p. 19

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Miniati 2009, Note 26, p.77

- ↑ Pope John XXIII (26 May 1960). "Canonizzazione di S. Gregorio Barbarigo". Homely of His Holiness Pope John XXIII (in Italian). Holy See. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Garrett Winter 1916, p. 184

- ↑ Cutler 2003

- ↑ 7.0 7.1

Hansen, Niels (1913). "Nicolaus Steno". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Hansen, Niels (1913). "Nicolaus Steno". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ History of Geology – Steno – Aber, James S. 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ Kooijmans 2007

- ↑ Wyse Jackson 2007

- ↑ Woods 2005, pp. 4 & 96

- ↑ Garrett Winter 1916, pp. 180, 182

- ↑ Office Of Papal Liturgical Celebrations. "Beatifications By Pope John Paul II, 1979–2000". Holy See. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ Kermit 2002

- ↑ Kooijmans 2004, p. 53. See

- ↑ René, Descartes. "The Origin of Tears". The Passions of the Soul. Jonathan Bennett. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Steno, Nicolaus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Steno, Nicolaus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press - ↑ Kooijmans, L. (2007) Gevaarlijke kennis, p. 99-100.

- ↑ Kardel 1990

- ↑ Kardel 1994, p. 1

- ↑ Kermit 2003

- ↑ Tubbs et al. 2010

- ↑ Andrault 2010

- ↑ Kooijmans (2007), p. 45.

- ↑ Breve storia della paleontologia, internet site of Centro dei Musei di Scienze Naturali, university of Naples Retrieved 10 January 2012

- ↑ Abbona 2002, Geologia. Colonna had been schooled in the collection of Ferrante Imperato, apothecary and virtuoso of Naples, who published his natural history notes in 1599

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Garrett Winter 1916, p. 182

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Brookfield 2004, p. 116

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Kunz 1918

- ↑ Molčanov, K. and Stilinović, V. (2014), Chemical Crystallography before X-ray Diffraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 53: 638–652. doi:10.1002/anie.201301319

- ↑ "Stephen A. Nelson, (Tulane U.) "Introduction to Earth Materials"" (PDF). Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Bishop Bl. Niels Stensen". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ "Niels Stensen". Whonamedit? A dictionary of medical eponyms. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "Pulchra sunt, quae videntur pulchriora quae sciuntur longe pulcherrima quae ignorantur. From a 1673 speech for the Copenhagen Anatomical Theatre". Stenomuseet.dk. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Kraus 2011, p. 35

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 36.7 Scherz 2002

- ↑ Israel 2002, pp. 251, 316

- ↑ "Skeptic files website". Skepticfiles.org. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ Perrini, Lanzino & Parenti 2010

- ↑ Nicolai Stenonis epistolae et epistolae ad eum datae quas cum prooemio ac notis germanice scriptis edidit Gustav Scherz. 2 tom, p. 997. Kopenhagen und Freiburg, Nordisk Forlag und Herder, 1952.

- ↑ "Niels Stensen chapel in San Lorenzo – Himetop". Himetop.wikidot.com. 21 March 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Kermit 2002, p. 21

- ↑ "The Steno Museum – Welcome". Stenomuseet.dk. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ Information about Stenonite on Mindat database, Retrieved on 26 November 2012.

- ↑ Michael Fleischer (1963), "New Mineral Names", American Mineralogist, 48, at 1178.

- ↑ "Niels-Stensen-Kirche Grevesmühlen" (in German). Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ "Niels Steensens Gymnasium" (in Danish). Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ Hom, Jennifer (2012). "Nicolas Steno's 374th Birthday". Doodles. Google. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ O'Carroll, Eoin (11 January 2012). "Nicolas Steno: The saint who undermined creationism". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ↑ Cavna, Michael (11 January 2012). "Nicolas Steno Google Doodle: Logo digs deep to celebrate Danish ‘father of geology’". Washington Post. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- Bibliography

- Abbona, Francesco (2002). "Geologia". In Strumia, Alberto; Tanzella-Nitti, Giuseppe. Dizionario Interdisciplinare di Scienza e Fede : Cultura Scientifica, Filosofia e Teologia. Città del Vaticano: Urbaniana University Press. ISBN 978-88-311-9265-1. Retrieved 12 January 2012. (Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Opus Dei)

- Kermit, Hans (2002). "The Life of Niels Stensen". In Ascani, Karen; Kermit, Hans; Skytte, Gunver. Niccolò Stenone (1638–1686) : anatomista, geologo, vescovo ; atti del seminario organizzato da Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsø e l'Accademia de Danimarca, lunedì 23 ottobre 2000. Roma: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider. ISBN 978-88-8265-213-5. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- Andrault, Raphaële (2010). "Mathématiser l'anatomie: La myologie de Stensen (1667)". Early Science and Medicine (in French) 15 (4): 505–536. doi:10.1163/157338210X516305.

- Kardel, Troels (1994). "Stensen's Myology in Historical Perspective". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 84 (1): 1–57. doi:10.2307/1006586. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- Brookfield, Michael E. (2004). Principles of stratigraphy. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publ. ISBN 978-1-4051-1164-5. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- Garrett Winter, John (1916). "Introduction – the Life of Steno". The prodromus of Nicolaus Steno's dissertation: concerning a solid body enclosed by progress of nature within a solid – an English version with an introduction and explanatory notes. Macmillan. pp. 175–187. (Public Domain)

Hansen, Niels (1913). "Nicolaus Steno". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Hansen, Niels (1913). "Nicolaus Steno". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Steno, Nicolaus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press See Archive.org for a scan of page 879.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Steno, Nicolaus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press See Archive.org for a scan of page 879.- Scherz, G. (2002). "Stensen, Niels, Bl.". In Catholic University of America. The New Catholic Encyclopedia. Volume 13 – Seq to The. Catholic University Press/Thomas Gale. pp. 508–509. ISBN 0-7876-4017-4.

- Cutler, Alan (2003). The Seashell on the Mountaintop: A Story of Science, Sainthood, and the Humble Genius Who Discovered a New History of the Earth. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-94708-6.

- Kardel, Troels (1990). "Niels Stensen's geometrical theory of muscle contraction (1667): A reappraisal". Journal of Biomechanics 23 (10): 953–65. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(90)90310-Y. PMID 2229093.

- Kunz, George F. (1918). "The Life and Work of Haüy". American Mineralogist 3 (6): 61–89. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- Israel, Jonathan I. (2002). Radical enlightenment — philosophy and the making of modernity 1650–1750. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925456-9.

- Kermit, Hans (2003). Niels Stensen, 1638–1686: The Scientist Who Was Beatified. Leominster, UK: Gracewing. pp. 82–83. ISBN 0-85244-583-0. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- Kooijmans, Luuc (2004). De doodskunstenaar — de anatomische lessen van Frederik Ruysch (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Bert Bakker. ISBN 978-90-351-2673-2. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- Kooijmans, Luuc (2007). Gevaarlijke kennis — inzicht en angst in de dagen van Jan Swammerdam (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Bert Bakker. ISBN 978-90-351-3250-4.

- Kraus, Max-Joseph (2011). Niels Stensen in Leiden (in German). Munich: GRIN Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-640-86454-6. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- Miniati, Stefano (2009). Nicholas Steno's challenge for Truth. Reconciling science and faith. FrancoAngeli. ISBN 88-568-2065-X.

- Tubbs, R. Shane; Mortazavi, Martin M.; Shoja, Mohammadali M.; Loukas, Marios; Cohen Gadol, Aaron A. (2010). "The bishop and anatomist Niels Stensen (1638–1686) and his contributions to our early understanding of the brain". Child's Nervous System (in Dutch) 27: 1–6. doi:10.1007/s00381-010-1236-5.

- Tubbs, R. Shane; Gianaris, Nicholas; Shoja, Mohammadali M.; Loukas, Marios; Cohen Gadol, Aaron A. (2010). ""The heart is simply a muscle" and first description of the tetralogy of "Fallot". Early contributions to cardiac anatomy and pathology by bishop and anatomist Niels Stensen (1638–1686)". International Journal of Cardiology 154 (3): 312–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.09.055. PMID 20965586.

- Perrini, Paolo; Lanzino, Giuseppe; Parenti, Giuliano Francesco (2010). "Niels Stensen (1638–1686): Scientist, Neuroanatomist, and Saint". Neurosurgery 67 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000370248.80291.C5. PMID 20559086.

- Sobiech, Frank (2009). "Nicholas Steno's way from experience to faith: Geological evolution and the original sin of mankind". In Rosenberg, Gary D. The Revolution in Geology from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment (GSM). Boulder, Co: Geological Society of America. pp. 179–186. ISBN 978-0-8137-1203-1.

- Hansen, Jens Morten (2009). "On the origin of natural history: Steno's modern, but forgotten philosophy of science". In Rosenberg, Gary D. The Revolution in Geology from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment (GSM). Boulder, Co: Geological Society of America. pp. 159–178. ISBN 978-0-8137-1203-1.

- Woods, Thomas E. (2005). How the Catholic Church built Western civilization. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publ. ISBN 0-89526-038-7.

- Wyse Jackson, Patrick N., ed. (2007). Four centuries of geological travel : the search for knowledge on foot, bicycle, sledge and camel. London: The Geological Society. ISBN 978-1-86239-234-2.

- Blessed Nicholas Steno (1638–1686). Natural-History Research and Science of the Cross by Frank Sobiech, in: Australian EJournal of Theology, August 2005, Issue 5, ISSN 1448-632

Further reading

- Wieh, Hermann (1988). Niels Stensen : sein Leben in Dokumenten u. Bildern (in German). Würzburg: Echter. ISBN 978-3-429-01165-9.

- Diederich, Georg, ed. (2011). Diener der Wahrheit – Niels Stensen (in German). Schwerin: Thomas-Morus-Bildungswerk. ISBN 978-3-9810202-6-7. Selected papers on the life and works of Niels Stensen.

- Porter, Ian Herbert (1963). "Thomas Bartholin (1616–80) And Niels Steensen (1638–86) Master And Pupil". Medical history 7 (2): 99–125. PMC 1034806. PMID 13985566.

- Holomanova, A.; Ivanova, A.; Brucknerova, I. (2002). "Niels Stensen Prestigious scholar of the 17th century". Bratisl Lek Listy 102: 90–93.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nicolaus Steno. |

|