Nicolae Constantin Batzaria

| Nicolae Constantin Batzaria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

November 20, 1874 Kruševo |

| Died |

January 28, 1952 (aged 77) Bucharest (Ghencea) |

| Pen name | Ali Baba, Moş Ene, Moş Nae |

| Occupation | short story writer, novelist, schoolteacher, folklorist, poet, journalist, politician |

| Nationality | Ottoman, Romanian |

| Ethnicity | Aromanian |

| Period | 1901-1944 |

| Genres | anecdote, children's literature, children's rhyme, comic strip, essay, fairy tale, fantasy, genre fiction, memoir, novella, satire, travel literature |

Nicolae Constantin Batzaria (Romanian pronunciation: [nikoˈla.e konstanˈtin bat͡saˈri.a], last name also Besaria, Basarya, Baţaria or Bazaria; also known under the pen names Moş Nae, Moş Ene and Ali Baba; November 20, 1874 – January 28, 1952), was a Macedonian-born Aromanian cultural activist, Ottoman statesman and Romanian writer. A schoolteacher and inspector of Aromanian education within Ottoman lands, he established his reputation as a journalist before 1908. During his thirties, he joined the clandestine revolutionary movement known as the Young Turks, serving as its liaison with Aromanian factions. The victorious Young Turk Revolution brought Batzaria to the forefront of Ottoman politics, ensuring him a seat in the Ottoman Senate, and he briefly served as Minister of Public Works under the Three Pashas. He was tasked with several diplomatic missions, including attending the London Conference of 1913, but, alerted by the Three Pashas' World War I alliances and the Young Turks' nationalism, he soon after quit the Ottoman political scene and left into voluntary exile.

Batzaria eventually settled in Romania and became a prolific contributor to Romanian letters, producing works of genre fiction and children's literature. Together with comic strip artist Marin Iorda, he created Haplea, one of the most popular characters in early Romanian comics. Batzaria also collected and retold fairy tales from various folkloric traditions, while publishing original novels for adolescents and memoirs of his life in Macedonia. A member of the Romanian Senate for one term, he was active on the staff of Romania's leading left-wing journals, Adevărul and Dimineaţa, as well as founder of the latter's supplement for children, before switching his allegiance to the right-wing Universul. Batzaria was persecuted and imprisoned by the communist regime, and spent his final years in obscure captivity.

Biography

Early life and activities

Batzaria was a native of Kruševo (Crushuva), a village in Ottoman-ruled Monastir region, presently in the Republic of Macedonia. His Aromanian family had numerous branches outside that region: migrant members had settled in the Kingdom of Romania, in Anatolia, and in the Khedivate of Egypt.[1] Nicolae grew up in Kruševo, where he studied under renowned Aromanian teacher Sterie Cosmescu.[1] He later attended a high school sponsored by the Kingdom of Romania in Bitola, and later the Faculties of Letters and Law at the University of Bucharest.[2][3][4] The young man became a dedicated disciple of Romanian nationalist theorist Nicolae Iorga, who was inaugurating his lectures in History during Batzaria's first year there.[5] He notably shared Iorga's belief, consolidated with time, that the Aromanians were not an isolated Balkan ethnicity, but part of larger Romanian ethnic community. As he himself explained, "the Romanian people [is] a unitary and indivisible body, regardless of the region wherein historical circumstances have settled it", and the "Macedonian Romanians" constituted "the most aloof branch of the Romanian trunk".[6]

Lacking funds for his tuition, Batzaria never graduated.[1] Instead, he earned his recognition as a journalist, educator and analyst. A polyglot, he could speak Turkish, Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian and French, in addition to his native Aromanian and the related Romanian language.[7] Literary critic and memoirist Barbu Cioculescu, who befriended Batzaria as a child, recalls that the Aromanian journalist "spoke all Balkan languages", and "perfect Romanian" with a "brittle" accent.[8]

While in Romania, Batzaria also began his collaboration with Romanian journals: Adevărul, Dimineaţa, Flacăra, Arhiva, Ovidiu and Gândul Nostru.[3][9] Also notable is his work with magazines published by the Aromanian diaspora. These publications depicted the Aromanians as a subgroup of the Romanian people.[10] They include Peninsula Balcanică ("The Balkan Peninsula", the self-styled "Organ for the Romanian interests in the Orient"), Macedonia and Frăţilia ("Brotherhood").[10] The latter, published from both Bitola and Bucharest, and then from the Macedonian metropolis of Thessaloniki, had Nicolae Papahagi and Nushi Tulliu on its editorial board.[11] Batzaria made his editorial debut with a volume of anecdotes, Părăvulii (printed in Bucharest in 1901).[3]

Batzaria returned to Macedonia as a schoolteacher, educating children at the Ioannina school, and subsequently at his alma mater in Bitola.[12] In 1899, he and his colleagues notably persuaded Take Ionescu, the Romanian Education Minister, to allocate some 724,000 lei as a grant to Macedonian schools, and virulently protested when later governments halved this annual income.[13] He afterward became chief inspector of the Romanian educational institutions in the Ottoman provinces of Kosovo and Salonika.[4][14] Historian Gheorghe Zbuchea, who researched the self-identification of Aromanians as a Romanian subgroup, sees Batzaria as "the most important representative of the national Romanian movement" among early 20th century Ottoman residents,[15] and "without doubt one of the most complex personalities illustrating the history of trans-Danubian Romanianism".[1] Batzaria's debut in Macedonian cultural debates came at a turning point: through her political representatives, Romania was reexamining the scope of her involvement in the Macedonian question, and asserting that it held no ambition to annex Aromanian land.[16]

From Macedonia, Nicolae Batzaria began a correspondent of Neamul Românesc, a brochure and later magazine published in Romania by his mentor Nicolae Iorga.[6] At that stage, Batzaria, with Tulliu, Nicolae Papahagi and Pericle Papahagi, founded the Association of Educationists in Service to the Romanian People of Turkey (that is, the Aromanians), a union of professionals based in Bitola. They were on mission to Romania, where their demand for more funding sparked lively debates among Romanian politicians, but Education Minister Spiru Haret eventually signed off a special Macedonian fund, worth 600,000 lei (later increased to over 1 million).[17] The group was also granted a private audience with King Carol I, who showed sympathy for the Aromanian campaign and agreed to receive Batzaria on several other occasions.[13] Perceived as a figure of importance among the Aromanian delegates, Batzaria also began his collaboration with the magazine Sămănătorul, chaired at the time by Iorga.[18]

Lumina, Deşteptarea and Young Turks affiliation

Nicolae Batzaria's nationalism, aimed specifically against the Greeks, became more evident in 1903, when he founded the Bucharest gazette Românul de la Pind ("The Romanian of the Pindus"). It was published under the motto Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes, and monitored the Greek offensive against Aromanian institutions in places such as Moloviştea, calling out for action against the "perfidious" and "inhumane" enemy.[19] In 1905, Batzaria's paper fused into Revista Macedoniei ("Macedonia Magazine"), put out by a league of exiles, the Macedo-Romanian Cultural Society.[19] Batzaria and his colleagues in Bitola put out Lumina ("The Light"). A self-styled "popular magazine for the Romanians of the Ottoman Empire", it divided its content into a "clean" Romanian and a smaller Aromanian section, aiming to show "the kinship of these two languages", and arguing that "dialects are preserved, but not cultivated."[20] Batzaria became, in 1904, its editorial director, taking over from founder Dumitru Cosmulei.[11]

Lumina was the first Aromanian magazine to be published within the lands of Rumelia (Turkey-in-Europe), and espoused a cultural agenda without political objectives, setting up the first popular library for Aromanian- and Romanian-speakers of Macedonian descent.[21] However, the Association of Educationists stated explicitly that its goal was to elevate the "national and religious sentiment" among "the Romanian people of the Ottoman Empire".[22] Lumina was noted for its better quality, receiving a 2,880 lei grant from Romania's government, but was no longer in print by late 1908.[19] Following a ban on political activities by Sultan Abdul Hamid II, Batzaria was arrested by local Ottoman officials, and experience which later served him in writing the memoir În închisorile turceşti ("In Turkish Prisons").[23] In May 1905, the Ottoman ruler decided to give recognition to some Aromanian demands, principally their recognition as a distinct entity within the imperial borders.[24]

Batzaria's contribution in the press was diversified in later years. With discreet help from Romanian officials, he and Nicolae Papahagi founded, in Thessaloniki, the French-language sheet Courrier des Balkans ("Balkan Dispatch", published from 1904).[25] It was specifically designed as a propaganda sheet for the Aromanian cause, informing its international readership about the Latin origins and philo-Romanian agenda of Aromanian nationalism.[26] He also worked on, or helped found, other Aromanian organs in the vernacular, including Glasul Macedoniei ("The Macedonian Voice")[9] and Grai Bun ("The Good Speech"). Late in 1906, Revista Macedoniei turned back into Românul de la Pind, struggling to survive as a self-funded national tribune.[19] Batzaria also replaced N. Macedoneanu as Grai Bun editor in 1907, but the magazine was under-financed and went bankrupt the same year.[11] His Romanian articles were still published in Iorga's Neamul Românesc, but also in the rival journal Viaţa Românească.[9]

In 1908, Batzaria founded what is seen by some as the first ever Aromanian-language newspaper, Deşteptarea ("The Awakening"), again from Thessaloniki.[3][7][27] The next year, it received a sponsorship of 6,000 lei from the Romanian government, and began agitating for the introduction of Aromanian classes in Ottoman primary schools.[11] Nevertheless, Deşteptarea went out of business in 1910.[11][27]

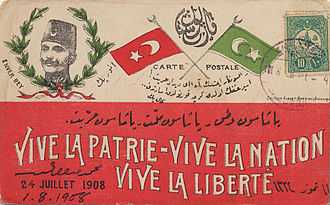

Beginning 1907, Batzaria took a direct interest in the development of revolutionary conspiracies which aimed to reshape the Ottoman Empire from within. Having first came in contact with İsmail Enver, he thereafter affiliated with the multi-ethnic Committee of Union and Progress, a clandestine core of the Young Turks movement.<ref name="eaturcia"/[28]> According to his own statements, he was acquainted with figures at the forefront of the Young Turks organizations: Mehmed Talat, Ahmed Djemal (the future "Three Pashas", alongside Enver), Mehmet Cavit Bey, Hafiz Hakki and others.[29] This was partly backed by Enver's notes in his diary, which includes the mention: "I was instrumental in bringing into the Society the first Christian members. For instance Basarya effendi."[30] Batzaria himself claimed to have been initiated into the society by Djemal and following a ritual similar to that of "nihilists" in the Russian Empire: an oath on a revolver placed inside a poorly lit room, while guarded by men dressed in black and red cloth.[4] Supposedly, Batzaria also joined the Freemasonry at some point in his life.[4]

Modern Turkish historian Kemal H. Karpat connects these events with a larger Young Turks agenda of attracting Aromanians into a political alliance, in contrast to the official policies of the rival Balkan states, all of which refused to recognize the Aromanian ethnicity as distinct.[31] Zbuchea passed a similar judgment, concluding: "Balkan Romanians actively supported the actions of the Young Turks, believing that they provided good opportunities for modernization and perhaps guarantees regarding their future."[15] Another Turkish researcher, M. Şükrü Hanioğlu, looks at the alliance from the point of view of a larger dispute between Greece (and the Greeks in Ottoman lands) on one hand, and, on the other, Ottoman leaders and their Aromanian subjects. Proposing that Aromanian activists, like their Albanian counterparts, "supported the preservation of Ottoman rule in Macedonia" primarily for fear of the Greeks, Hanioğlu highlights the part played by British mediators in fostering the Ottoman-Aromanian entente.[32] He notes that, "with the exception of the Jews", Aromanians were the only non-Islamic community to be drawn into the Ottomanist projects.[33]

Ottoman senator and minister

In 1908, the Aromanian intellectual was propelled to high office by the Young Turk Revolution and the Second Constitutional Era: the party rewarded his contribution, legally interpreted as "high services to the State", by assigning him a special non-elective seat in the Ottoman Senate (a status similar to that of another Young Turk Aromanian, Filip Mişea, who became a deputy).[34] As Zbuchea notes, Batzaria was unqualified for the office, as he was neither forty years old nor a distinguished bureaucrat, and only owed his promotion to his conspiratorial background.[35] By then, Batzaria is said to have also become a personal friend of the new sultan, Mehmed V,[9] and of Education Minister Abdurrahman Şeref, who reportedly shared his reverence for Nicolae Iorga.[36] A regular contributor to Le Jeune Turc and other newspapers based in Istanbul, the Aromanian campaigner was also appointed vice-president of the Turkish Red Crescent, a humanitarian society, which provided him with close insight into the social contribution of Muslim women volunteers, and, through extension, an understanding of Islamic feminism.[37]

The next few years were a period of maximal autonomy for Mehmed's Aromanian subjects, who could elect their own local government, eagerly learned Ottoman Turkish, and, still committed to Ottomanism, were promoted within the bureaucratic corps.[38] The community was still dissatisfied with various issues, most of all their automatic inclusion in the millet of Ottoman Greeks. Batzaria was personally becoming involved in a dispute with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, campaigning among the Turks for the recognition of a separate Aromanian bishopric.[39] The failure of this project, like the underrepresentation of Aromanians in the Senate, caused some of Batzaria's fellow activists to feel disgruntled.[40]

In 1912, during the First Balkan War, the partition of Macedonia put a stop to Românul de la Pind, which closed down at the same time as other Aromanian nationalist papers.[41] However, Batzaria's political career was advanced further by Enver's military coup: he became Minister of Public Works in Enver's cabinet, but without interrupting his journalistic activities.[4][42] It was also he who represented the executive at the London Conference, where he acknowledged the Ottoman defeat.[4][43][44] Against the law which specified that members of the Ottoman executive could not serve in the Senate, Batzaria did not lose his seat.[45] As was later revealed, he continued to act as a partisan of Romanian policies, and sent secret reports to his friend, King Carol I of Romania.[13] In early 1914, Le Jeune Turc published his praise for Iorga and the Bucharest Institute of South-East European Studies.[46]

As Ottoman administrators were being expelled from the Balkans, Batzaria and fellow Aromanian intellectuals tended to support the doomed project of an independent, multi-ethnic, Macedonia.[47] In the short peaceful hiatus which followed his return from London, Batzaria represented the empire in secret talks with Romania's Titu Maiorescu government, negotiating a new alliance against the victorious Kingdom of Bulgaria.[48] As he himself recalled, the request was refused by Romanian politicians, who stated that they wished to avoid attacking other Christian nations.[49] The Ottoman approach however resonated with Romania's intentions, and both states eventually defeated Bulgaria in the Second Balkan War.[50]

Relocation to Romania

The following years brought a clash of interests between the Three Pashas and Batzaria. Already alarmed by the officialized Turkification process,[4][15][51] the Aromanian intellectual proved himself an opponent of the new policies which linked the Ottoman realm to the German Empire, Bulgaria and the other Central Powers.[52] In 1916, two years into World War I, he left Istanbul for neutral Switzerland.[4][53] He was by then a correspondent for Iorga's new magazine, Ramuri.[6]

Nicolae Batzaria eventually resettled in Bucharest. He embarked on a career in writing, publishing a succession of fiction and nonfiction volumes in Romanian. He was, in January 1919, a co-founder of Greater Romania's original journalists' trade union (Union of Professional Journalists),[54] and, in 1921, published his În închisorile turceşti with Editura Alcaly.[55] He later produced a series of books detailing the lives of women in the Ottoman Empire and the modern Turkish state: Spovedanii de cadâne. Nuvele din viaţa turcească ("Confessions of Turkish Odalisques. Novellas from Turkish Life", 1921), Turcoaicele ("The Turkish Women", 1921), Sărmana Lila. Roman din viaţa cadânelor ("Poor Leila. A Novel from the Life of Odalisques", 1922), Prima turcoaică ("The First of Turkish Women", n.d.), as well as several translations of foreign books on this subject.[56] One of his stories about Ottoman womanhood, Vecina dela San-Stefano ("The Neighbor of Yeşilköy"), was published by the literary review Gândirea in its June 1922 issue.[57] Around the same time, the Viaţa Românească publishers issued his booklet România văzută de departe ("Romania Seen from a Distance"), a book of essays which sought to revive confidence and self-respect among Romanian citizens.[58]

A member of the People's Party, Batzaria served a term in the Senate of Greater Romania (coinciding with Alexandru Averescu's term as Premier).[4][59] By 1926, he had rallied with the opposition Romanian National Party (PNR). Included in its Permanent Delegation together with his old acquaintance Nicolae Iorga, he approved of PNR's fusion with the Romanian Peasantists, affiliating with the resulting National Peasants' Party (PNŢ).[60] He also participated in meetings of the Cultural League for the Unity of All Romanians (presided upon by Iorga), including a 1929 rally in Cluj city.[61]

During the interwar period, he also became a regular contributor to the country's main left-wing dailies: Adevărul and Dimineaţa. The journals' owners assigned Batzaria with the task of managing and editing a junior version of Dimineaţa, Dimineaţa Copiilor ("The Children's Morning"). Story goes that he was not just managing the supplement, but in effect writing down most content for each issue.[62] While at Adevărul, Batzaria stood accused by right-wing competitors of excessively promoting the National Peasantist leader Iuliu Maniu in view of the 1926 election. A nationalist newspaper, Ţara Noastră, argued that Batzaria's political columns were effectively coaching the public to vote PNŢ, and mocked their author as "a former Young Turk and ministerial colleague of that famous [İsmail] Enver-bey".[63] Like the PNŢ, the Adevărul journalist proposed the preservation of communal and regional autonomy in Greater Romania, denouncing centralization schemes as "ferocious reactionarism".[64] A while after, Batzaria drew attention to himself for writing, in Dimineaţa, about the need to protect the religious and communal liberties of the Jewish minority. The National-Christian Defense League, an antisemitic political faction, reacted strongly against his arguments, accusing Batzaria of having "sold his soul" to the Jewish owners of Adevărul, and to "kike interests" in general.[61] The year 1928 saw Batzaria protesting against the escalation of violence against journalists. His Adevărul piece was prompted by a brawl at the offices of Curentul daily, as well as by attacks on provincial newspapers.[65]

Later activity

Batzaria still maintained an interest in propagating the cause of Aromanians. The interwar years saw him joining the General Board of the Macedo-Romanian Cultural Society, of which he was for a while President.[66] He was one of the high-level Aromanian intellectuals who issued public protests when, in 1924, the Greek Gendarmes organized a crackdown against Aromanian activism in Pindus.[67] In 1927, Societatea de Mâine journal featured one of Batzaria's studies on the ethnic minorities of the Balkans, where he contrasted the persecution of Aromanians in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia with their "unexpected" toleration in Greece.[68]

In 1928, Batzaria was a judge for a national Miss Romania beauty contest, organized by Realitatea Ilustrată magazine and journalist Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaş (the other members of this panel being female activist Alexandrina Cantacuzino, actress Maria Giurgea, politician Alexandru Mavrodi, novelist Liviu Rebreanu and visual artists Jean Alexandru Steriadi and Friedrich Storck).[69] As an Adevărul journalist, Batzaria nevertheless warned against politically militant feminism and women's suffrage, urging women to find their comfort in marriage.[70] Speaking in 1930, he suggested that the idea of a feminist party in gender-biased Romania was absurd, arguing that women could either support their husbands' political activities or, at most, affiliate with the existing parties.[71]

Batzaria's work in children's literature, taking diverse forms, was often published under the pen names Moş Nae ("Old Man Nae", a term of respect applied to the hypocorism of Nicolae) and Ali Baba (after the eponymous character in One Thousand and One Nights).[72] Another variant he favored was Moş Ene.[73] By 1925, Batzaria had created the satirical character Haplea (or "Gobbles"), whom he made into a protagonist for some of Romania's first comic strips.[44][74][75][76] A Christmas 1926 volume, comprising 73 Haplea stories, was welcomed at the time as one of the best books for children.[77] Other characters created by Batzaria in various literary genres include Haplina (the female version and regular companion of Haplea), Hăplişor (their child), Lir and Tibişir (known together as doi isteţi nătăfleţi, "two clever gawks"), and Uitucilă (from a uita, "to forget").[78]

The graphics to Batzaria's rhymed captions were provided by caricaturist Marin Iorda, who also worked on a cinema version of Haplea (one of the first samples of Romanian animation).[44][76] It was a compendium of the Dimineaţa comics, with both Iorda and Batzaria (the credited screenwriter) drawn in as supporting characters.[76] Premiered in December 1927 at Cinema Trianon of Bucharest, it had been in production for almost a year.[76] From 1929, Batzaria also took over as editor and host of the children's show Ora Copiilor, on National Radio.[79] This collaboration lasted until 1932, during which time Batzaria also gave radio conferences on Oriental subjects (historical Istanbul, the Albanian Revolt of 1912 and the Quran) or on various other topics.[79]

By 1930, Nicolae Constantin Batzaria also became known for his genre fiction novels, addressed to a general public and registering much success. Among these were Jertfa Lilianei ("Liliana's Sacrifice"), Răpirea celor două fetiţe ("The Kidnapping of the Two Little Girls"),[78] Micul lustragiu ("The Little Shoeshiner") and Ina, fetiţa prigonită ("Ina, the Persecuted Little Girl").[80] His main fairy tale collection was published as Poveşti de aur ("Golden Stories").[81] Also in 1930, he worked state-approved textbooks for the 2nd, 3rd and 4th grades, co-authored with P. Puchianu and D. Stoica and published by Scrisul Românesc of Craiova.[82]

In addition, Batzaria took to the applied study of philology. He reportedly consulted researcher Şerban Cioculescu about the Balkan origins of classical Romanian dramatist Ion Luca Caragiale.[8] His interest in Oriental themes also touched his reviews of works by other writers, such as his 1932 essay on the Arabic and Persian motifs reused by Caragiale in the Kir Ianulea story.[83] Caragiale's acquaintance with Ottoman sources was also the subject of Batzaria's last known radio conference, aired in August 1935.[84] A few months later, Batzaria was appointed Commissioner of the "Bucharest Month" Exhibit, organized with official support and attended by Romanian King Carol II.[85]

Final years, persecution and death

In mid 1936, Batzaria parted with Dimineaţa and joined its right-wing and nationalist rival, Universul, becoming Universul publisher.[86] He was then appointed editor of Universul Copiilor ("Children's Universe"), the Universul youth magazine, which took up his Haplea stories and comics. According to literary critic Gabriel Dimisianu, who was a fan of the magazine in his boyhood, Universul Copiilor was "very good".[87]

Batzaria also switched to National Liberal Party politics, and represented the National Liberal group on the General Council of Bucharest.[88] At Universul, he became involved in political disputes facing the leftists and rightists, siding with the latter. As observed by historian Lucian Boia, this was a common enough tendency among the Aromanian elite and, as Batzaria himself put it in one of his Universul texts, was read as a "strengthening of the Romanian element."[89]

The writer also became directly involved in the conflict opposing Universul and Adevărul, during which the latter was accused of being a tool for "communism". He urged the authorities to repress what he argued was a communist conspiracy, led by his former employers.[90] In manifest contrast to Adevărul, and in agreement with Romanian fascists, Batzaria supported the Italian invasion of Abyssinia as a step forward for "that sound and creative Latin civilization."[91]

Batzaria expressed sympathy toward the fascist and antisemitic "Iron Guard" movement. This political attitude touched his editorial pieces concerning the Spanish Civil War. He marked the death of Iron Guardist politico Ion Moţa, in service to the Francoist side, likening him to heroes such as Giuseppe Garibaldi and Lafayette (see Funerals of Ion Moţa and Vasile Marin).[92]

Batzaria was nevertheless marginalized for the larger part of World War II, when Romania came under the rule of far right and fascist regimes (the Iron Guard's National Legionary State and the authoritarian system of Conducător Ion Antonescu).[52] He was nevertheless featured and reviewed in an issue of Familia magazine, where he discussed the loss of Northern Transylvania, and compared the plight of its inhabitants with that of the Aromanians.[93] Batzaria's 50th book of stories also saw print, as Regina din Insula Piticilor ("The Queen of Dwarf Island"), set to coincide with Christmas 1940.[94] He also put out the Universul children's almanac.[95]

In 1942, after the Guard's downfall, Familia published a posthumous homage to Nicolae Iorga, who had been assassinated by the Guard in 1940.[96] From November 1942, Universul hosted a new series of his political articles, on the subject of "Romanians Abroad". Reflecting the Antonescu regime's rekindled interest in the Aromanian issue, these offered advice on standardizing the official Aromanian dialect.[97] At around that time, Universul Copillor began contributing to Antonescu's propaganda effort, supporting Romania's Eastern Front efforts, against the Soviet Union.[98][99] With its comics and its editorial content, the magazine spearheaded a xenophobic campaign, targeting the Frenchified culture of the upper class, ridiculing the Hungarians of Northern Transylvania, and portraying the Soviets as savages.[99] In addition to his work as editor, Batzaria focused on translating stories by the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, which saw print under the Moş Ene signature in stages between 1942 and 1944.[73]

The war's end and the rise of the Communist Party made Batzaria a direct target for political persecution. Shortly after the August 23 Coup, the communist press began targeting Batzaria with violent rhetoric, calling for his exclusion from the Romanian Writers' Society (or SSR): "in 1936, when Ana Pauker stood trial, [Batzaria] joined the enemies of the people, grouped under Stelian Popescu's quilt at Universul, instigating in favor of racial hatred".[100] The party organ, Scînteia, identified Universul Copiilor as a "fascist and anti-Soviet" publication, noting: "The traitor Batzaria, aka Moş Nae, should be aware that there is no longer a place for him in today's Romanian media."[98]

Batzaria was stripped of his SSR membership in the early months of 1945,[101] and, in 1946, Universul Copiilor was suppressed.[87] The consolidation of a communist regime in 1947-1948 led to his complete ostracizing, beginning when he was forced out of his house by the authorities (an action which reportedly caused the destruction of all his manuscripts through neglect).[52]

Sources diverge on events occurring during Batzaria's final years. Several authors mention that he became a political prisoner of the communists.[3][8][88][102][103] According to Karpat, Batzaria died in poverty at his Bucharest house during the early 1950s.[52]

Later research however suggests that this occurred in 1952, at a concentration camp. The most specific such sources mentions that his life ended at a penal facility located in Bucharest's Ghencea district.[3][102] Scientist Claudiu Mătasă, who shared his cell there, recalled: "His stomach ill, [Batzaria] basically died in my arms, with me taking as much care of him as circumstances would allow..."[102] Barbu Cioculescu gives a more complex account: "In very old age [Batzaria] was arrested, not for being a right-wing man, as he had not in fact been one, but for having served as a city councilor. A spinal cancer sufferer, he died in detention [...] not long after having been sentenced".[8] According to historian of journalism Marin Petcu, Batzaria's confinement was effectively a political assassination.[104]

Work

Fiction

Anthumous editions of Nicolae Constantin Batzaria's work include some 30 volumes, covering children's, fantasy and travel literature, memoirs, novels, textbooks, translations and various reports.[105] According to his profile at the University of Florence Department of Neo-Latin Languages and Literatures, Batzaria was "lacking in originality but a talented vulgarizer".[3] Writing in 1987, children's author Gica Iuteş claimed that the "most beautiful pages" in Batzaria's work were those dedicated to the youth, making Batzaria "a great and modest friend of the children".[78]

His short stories for children generally build on ancient fairy tales and traditional storytelling techniques. A group among these accounts retell classics of Turkish, Arabic and Persian literatures (such as One Thousand and One Nights), intertwined with literary styles present throughout the Balkans.[105] This approach to Middle Eastern themes was complemented by borrowings from Western and generally European sources, as well as from the Far East. The Poveşti de aur series thus includes fairy tales from European folklore and Asian folktales: Indian (Savitri and Satyavan), Spanish (The Bird of Truth), German, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Scandinavian and Serbian.[81] Other works retold modern works of English children's literature, including Hugh Lofting's The Story of Doctor Dolittle.[8] His wartime renditions from Andersen's stories covered The Emperor's New Clothes, The Ugly Duckling and The Little Mermaid.[73]

Among the writer's original contributions was a series of novels for the youth. According to literary critic Matei Călinescu, who recalled having enjoyed these works as a child, they have a "tearjerker" and "melodramatic" appeal.[80] Essayist and literary historian Paul Cernat calls them "commercial literature" able to speculate public demand, and likens them to the texts of Mihail Drumeş, another successful Aromanian author (or, beyond literature, to the popular Aromanian singer Jean Moscopol).[106] Other stories were humorous adaptations of the fairy tale model. They include Regina din Insula Piticilor, in which Mira-Mira, Queen of the Dolls, and her devoted servant Grăurel fend off the invasion of evil wizards.[94] Batzaria is also credited with having coined popular children's rhymes, such as:

|

Sunt soldat şi călăreţ,

|

I'm a soldier and a cavalryman, |

Batzaria's Haplea was a major contribution to Romanian comics culture and interwar Romanian humor, and is ranked by comics historiographer Dodo Niţă as the top Romanian series of all times.[75] The comics, the books and the animated film all ridicule the boorish manners of peasants, and add comic effect to the clash of cultures between city and village lives.[76] The scripts were not entirely original creations: according to translator and critic Adrian Solomon, one Haplea episode retold a grotesque theme with some tradition in the Romanian folklore (the story of Păcală), that in which the protagonist murders people for no apparent reason.[107] Another influence on Haplea, as noted by Batzaria reviewers, was the 19th-century fabulist and shorty author Anton Pann.[77]

Memoirs and essays

A large segment of Batzaria's literary productions was constituted by subjective recollections. Kemal H. Karpat, according to whom such writings displayed the attributes of "a great storyteller" influenced by both Romanian classic Ion Creangă and the Ottoman meddahs, notes that they often fail to comply with orthodox attested timelines and accuracy checks.[108] Reviewing În închisorile turceşti, journalist D. I. Cucu recognized Batzaria as an entertaining raconteur, but noted that the text failed to constitute a larger fresco of the Aromanian "denationalization".[55] Cucu described the account as entirely opposed to the romanticized narratives of Ottoman affairs, by Pierre Loti or Edmondo De Amicis.[55] More such criticism came from Batzaria's modernist contemporary Felix Aderca, who suggested that Batzaria and Iorga (himself an occasional writer) had "compromised for good" the notion of travel literature.[109]

The main book in this series is Din lumea Islamului. Turcia Junilor Turci ("From the World of Islam. The Turkey of the Young Turks"), which traces Batzaria's own life in Macedonia and Istanbul. Its original preface was a contribution of Iorga, who recommended it for unveiling "that interesting act in the drama of Ottoman decline that was the first phase of Ottoman nationalism".[4] In Karpat's opinion, these texts bring together the advocacy of liberalism, modernization and Westernization, flavored with "a special understanding of the Balkan and Turkish societies".[105] Batzaria's books also describe Christianity as innately superior to Islam, better suited for modernization and education, over Islamic fatalism and superstition.[4][110] His extended essay on women's rights and Islamic feminism, Karpat argues, shows that the Young Turks' modernizing program anticipated the Kemalist ideology of the 1920s.[56] Overall, Batzaria gave voice to an anticlerical agenda targeting the more conservative ulema, but also the more ignorant of Christian priests, and discussed the impact of religious change, noting that the Young Turks eventually chose a secular identity over obeying their Caliphate.[111]

În închisorile turceşti and other such writings record the complications of competing nationalisms in Ottoman lands. Batzaria mentions the Albanian landowners' enduring reverence for the Ottoman Dynasty, and the widespread adoption of the vague term "Turk" as self-designation in the Balkan Muslim enclaves.[112] Likewise, he speaks about the revolutionary impact of ethnic nationalism inside the Christian millet, writing: "it was not rare to see in Macedonia a father who would call himself a Greek without actually being one [...], while one of his sons would become a fanatical Bulgarian, and the other son would turn into a killer of Bulgarians."[113] While theorizing an Aromanian exception among the "Christian peoples" of the Ottoman-ruled Balkans, in that Aromanians generally worked to postpone the evident Ottoman decline, Batzaria also argued that the other ethnic groups were innately hostile to the Young Turks' liberalism.[113] However, Karpat writes, "Batzaria believed, paradoxically, that if the Young Turks had remained genuinely faithful to their original liberal ideals they might have succeeded in holding the state together."[113]

According to Batzaria, the descent into civil war and the misapplication of liberal promises after the Young Turk Revolution made the Young Turk executive fall back on its own ethnic nationalism, and then on Turkification.[4][51] That policy, the author suggested, was ineffective: regular Turks were poor and discouraged, and Europe looked with displeasure on the implicit anti-colonialism of such theories.[114] In Din lumea Islamului, Batzaria looks to the individuals who pushed for this policy. He traces psychological sketches of İsmail Enver (who, although supportive of a "bankrupt" Pan-Turkic agenda, displayed "an insane courage and an ambition that kept growing and solidifying with every step"), Ahmed Djemal (an uncultured chauvinist), Mehmed Talat ("the most sympathetic and influential" of the Young Turk leaders, "never bitten by the snake of vanity").[4]

Batzaria also noted that Turkification alienated the Aromanians, who were thus divided and forced to cooperate with larger ethnic groups within their millet just before the First Balkan War, and that cooperation between them and the Bulgarians was already unfeasible before the Second War.[115] According to Betzaria's anecdotal account, he and the Ottoman Armenian politician Gabriel Noradunkyan rescued Istanbul from a Bulgarian siege, by spreading false rumors about a cholera epidemic in the city.[4] His explanation of World War I depicts the Central Powers alliance as a gamble by the most daring of the Young Turks.[116] Deploring the repeated acts of violence perpetrated by the Ottomans against members of the Armenian community (Noradunkyan included),[4] Batzaria also maintains that the Armenian Genocide was primarily perpetrated by rogue Ottoman Army units, Hamidieh regiments and other Kurds.[4][117] He claims to have unsuccessfully asked the Ottoman Senate to provide Armenians with weaponry against the "bandits carrying a firman".[4]

In other works, Batzaria expanded his range, covering the various problems of modernity and cultural identity. România văzută de departe, described by D. I. Cucu as a "balm" for patriotic feeling, illustrated with specific examples the hopes and aspirations of philo-Romanians abroad: a Romanian-Bulgarian priest, a Timok Romanian mayor, an Aromanian schoolteacher, etc.[58] The 1942 series of essays offered some of Batzaria's final comments on the issue of Aromanian politics. Although he offered implicit recognition to the existence of an "Aromanian dialect", Batzaria noted that Romanian had always been seen by him and his colleagues as the natural expression of Aromanian culture.[97] On the occasion, he referred to "the Romanian minorities" of the Balkans as "the most wronged and persecuted" Balkan communities.[118]

Legacy

The work of Nicolae Constantin Batzaria was the subject of critical reevaluation during the last decades of the communist regime, when Romania was ruled by Nicolae Ceauşescu. Writing at the time, Kemal H. Karpat argued: "Lately there seems to be a revived interest in [Batzaria's] children's stories."[52] During the period, Romania's literary scene included several authors whose talents had been first noticed by Batzaria when, as children, they sent him their debut works. Such figures include Ştefan Cazimir,[62] Barbu Cioculescu[119] and Mioara Cremene.[120]

Batzaria's various works for junior readers were published in several editions beginning in the late 1960s,[52] and included reprints of Poveşti de aur with illustrations by Lívia Rusz.[121] Writing the preface to one such reprint, Gica Iuteş defined Batzaria as "one of the eminent Aromanian scholars" and "a master of the clever word", while simply noting that he had "died in Bucharest in the year 1952."[122] Similarly, the 1979 Dicţionarul cronologic al literaturii române ("Chronological Dictionary of Romanian Literature") discussed Batzaria, but gave no clue as to his death.[88] In tandem with this official recovery, Batzaria's work became an inspiration for the dissident poet Mircea Dinescu, the author of a clandestinely circulated satire which compared Ceauşescu to Haplea and referred to both as figures of destruction.[123][124]

Renewed interest in Batzaria's work followed the 1989 Revolution, which signified the communist regime's end. His work was integrated into new reviews produced by literary historians, and awarded a sizable entry in the 2004 Dicţionar General al Literaturii Române ("The General Dictionary of Romanian Literature"). The character of this inclusion produced some controversy: taking Batzaria's entry as a study case, critics argued that the book gave too much exposure to marginal authors, at the detriment of writers from the Optzecişti generation (whose respective articles were comparatively shorter).[125][126] The period saw a number of reprints from his work, including the Haplea comics[74] and a 2003 reissue of his Haplea la Bucureşti ("Haplea in Bucharest"), nominated for an annual prize in children's fiction.[127] Fragments of his writings, alongside those of George Murnu, Hristu Candroveanu and Teohar Mihadaş, were included in the Romanian Academy's standard textbook for learning Aromanian (Manual de aromână-Carti trâ înviţari armâneaşti, edited by Matilda Caragiu-Marioţeanu and printed in 2006).[128]

Batzaria was survived by a daughter, Rodica, who died ca. 1968.[52] She had spent much of her life abroad, and was for a while married to painter Nicolae Dărăscu.[8] Batzaria's great-granddaughter, Dana Schöbel-Roman, was a graphic artist and illustrator, who worked with children's author Grete Tartler on the magazine Ali Baba (printed in 1990).[129]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Zbuchea (1999), p.79

- ↑ Karpat, p.563; Zbuchea (1999), p.62-63, 79. See also Batzaria (1942), p.37-39

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 (Romanian) "Batzaria Nicolae", biographical note in Cronologia della letteratura rumena moderna (1780-1914) database, at the University of Florence's Department of Neo-Latin Languages and Literatures; retrieved August 19, 2009

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 (Romanian) Eduard Antonian, "Turcia, Junii Turci şi armenii în memoriile lui Nicolae Batzaria", in the Armenian-Romanian community's Ararat, Nr. 8/2003, p.6

- ↑ Batzaria (1942), p.37-38

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Batzaria (1942), p.41

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Karpat, p.563

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 (Romanian) Barbu Cioculescu, "Soarele Cotrocenilor", in Litere, Nr. 2/2011, p.11

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Zbuchea (1999), p.82

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Zbuchea (1999), p.81-82

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Gică, p.6

- ↑ Karpat, p.563; Zbuchea (1999), p.79-80

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Zbuchea (1999), p.80

- ↑ Hanioğlu, p.259; Karpat, p.563; Zbuchea (1999), p.79, 82

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Gheorghe Zbuchea, "Varieties of Nationalism and National Ideas in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Southeastern Europe", in Răzvan Theodorescu, Leland Conley Barrows (eds.), Studies on Science and Culture. Politics and Culture in Southeastern Europe, UNESCO-CEPES, Bucharest, 2001, p.247. ISBN 92-9069-161-6

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.63-65

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.80-81

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.80, 81. See also Batzaria (1942), p.41

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Gică, p.7

- ↑ Gică, p.6-7

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.58, 81. See also Gică, p.6-7

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.81

- ↑ Karpat, p.567-568

- ↑ Gică, p.8; Zbuchea, p.67, 72-73, 84, 85, 90, 94-95, 116, 139, 142, 191-192, 241, 265

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.82. See also Gică, p.7-8

- ↑ Gică, p.7-8

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 (Aromanian) Agenda Armâneascâ, at Radio Romania International, April 14, 2009; retrieved August 20, 2009

- ↑ Karpat, p.563; Zbuchea (1999), p.78-79, 82-84

- ↑ Karpat, p.563, 569. See also Zbuchea (1999), p.79, 83-84

- ↑ Karpat, p.569

- ↑ Karpat, p.571-572

- ↑ Hanioğlu, p.259-260

- ↑ Hanioğlu, p.260

- ↑ Hanioğlu, p.259; Karpat, p.563, 569, 571, 576-577. See also Zbuchea (1999), p.78-79, 83-84

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.83-84, 283

- ↑ Batzaria (1942), p.38-39

- ↑ Karpat, p.563-564

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.84-99, 109

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.83, 99-101, 143-144, 146, 155

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.100-101, 155-156

- ↑ Gică, p.7, 8

- ↑ Hanioğlu, p.468; Karpat, p.564. See also Zbuchea (1999), p.83, 84

- ↑ Karpat, p.564, 569-570; Zbuchea (1999), p.79

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Gobbles" (with biographical notes), in the Romanian Cultural Institute's Plural Magazine, Nr. 30/2007

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.84

- ↑ (Romanian) "Informaţiuni", in Românul (Arad), Nr. 32/1914, p.8 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.109-110

- ↑ Karpat, p.564, 580; Zbuchea (1999), p.108-109. See also Hanioğlu, p.468

- ↑ Karpat, p.580; Zbuchea (1999), p.109

- ↑ Karpat, p.564, 580

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Karpat, p.577-584

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 52.5 52.6 Karpat, p.564

- ↑ Karpat, p.564; Zbuchea (1999), p.84

- ↑ (Romanian) G. Brătescu, "Uniunea Ziariştilor Profesionişti, 1919 - 2009. Compendiu aniversar", in Mesagerul de Bistriţa-Năsăud, December 11, 2009

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 (Romanian) D. I. Cucu, "Cărţi şi reviste. N. Batzaria, În închisorile turceşti", in Gândirea, Nr. 11/1921, p.211 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Karpat, p.567

- ↑ (Romanian) N. Batzaria, "Vecina dela San-Stefano", in Gândirea, Nr. 5/1922, p.90-93 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 (Romanian) D. I. Cucu, "Cărţi şi reviste. N. Batzaria, România văzută de departe", in Gândirea, Nr. 4/1922, p.80-81 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ Karpat, p.564; Zbuchea (1999), p.79

- ↑ (Romanian) "Frontul Democratic", in Chemarea Tinerimei Române, Nr. 23/1926, p.23 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 (Romanian) Şt. Peneş, "Jos masca Domnule Batzaria!", in Înfrăţirea Românească, Nr. 19/1929, p.221-222 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 (Romanian) Ştefan Cazimir, "Dimineaţa copilului", in România Literară, Nr. 19/2004

- ↑ (Romanian) Alexandru Hodoş, "Însemnări. Însuşiri profesionale", in Ţara Noastră, Nr. 13/1926, p.423 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ Marilena Oana Nedelea, Alexandru Nedelea, "Law of 24 June 1925 – Administrative Unification Law. Purpose, Goals, Limits", in the , in the Ştefan cel Mare University of Suceava's Annals (Fascicle of The Faculty of Economics and Public Administration), Nr. 1 (13)/2011, p.346

- ↑ Petcu, p.60

- ↑ (Romanian) Traian D. Lazăr, "Din istoricul Societăţii de Cultură Macedo-române", in , in Revista Română (ASTRA), Nr. 3/2011, p.23-24

- ↑ (Romanian) Delavardar, "Raiul aromânilor", in Cultura Poporului, Nr. 6/1924, p.1 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ (Romanian) N. Batzaria, "Minorităţile etnice din Peninsula Balcanică", in Societatea de Mâine, Nr. 25-26, June–July 1927, p.323-325 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ (Romanian) Dumitru Hîncu, "Al. Tzigara-Samurcaş - Din amintirile primului vorbitor la Radio românesc", in România Literară, Nr. 42/2007

- ↑ Maria Bucur, "Romania", in Kevin Passmore (ed.), Women, Gender, and Fascism in Europe, 1919-45, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2003, p.72. ISBN 0-7190-6617-4

- ↑ (Romanian) "Ancheta ziarului Universul 'Să se înscrie femeile în partidele politice?', Ziarul Nostru, anul IV, nr. 2, februarie 1930", in Ştefania Mihăilescu, Din istoria feminismului românesc: studiu şi antologie de texte (1929-1948), Polirom, Iaşi, 2006, p.116. ISBN 973-46-0348-5 (e-book version at the Aletta Institute)

- ↑ Batzaria (1987), passim; Karpat, p.564

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Mihaela Cernăuţi-Gorodeţchi, notes to Hans Christian Andersen, 14 poveşti nemuritoare, Institutul European, Iaşi, 2005, p.20, 54, 78, 103. ISBN 973-611-378-7

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 (Romanian) Maria Bercea, "Incursiune în universul BD", in Adevărul, June 29, 2008

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 (Romanian) Ioana Calen, "Cărtărescu e tras în bandă - Provocarea desenată", in Cotidianul, June 13, 2006

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 76.4 (Romanian) Alex Aciobăniţei, "Filmul românesc între 1905–1948 (18). Arta animaţiei nu a început cu Gopo!", in Timpul, Nr. 72/2004, p.23

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 (Romanian) Ion Băilă, "Literatură pentru copii. Haplea de N. Batzaria", in Societatea de Mâine, Nr. 49-50, December 1926, p.766 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 Iuteş, in Batzaria (1987), p.3

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Muşeţeanu, p.41-42

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Matei Călinescu, Ion Vianu, Amintiri în dialog. Memorii, Polirom, Iaşi, 2005, p.76. ISBN 973-681-832-2

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Batzaria (1987), passim

- ↑ (Romanian) "Cărţi şcolare", in Învăţătorul, Special Issue, August 20, 1930, p.37 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ (Romanian) Florentina Tone, "Scriitorii de la Adevĕrul", in Adevărul, December 30, 2008

- ↑ Muşeţeanu, p.42

- ↑ Illustration 11, in Boia

- ↑ Boia, p.66-67, 70; Karpat, p.564

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 (Romanian) Mircea Iorgulescu, Gabriel Dimisianu, "Prim-plan Gabriel Dimisianu. 'Noi n-am crezut că se va termina' ", in Vatra, Nr. 3-4/2005, p.69

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 (Romanian) Barbu Cioculescu, "Cum se citeşte un dicţionar", in Luceafărul, Nr. 33/2011

- ↑ Boia, p.66

- ↑ Hans-Christian Maner, Parlamentarismus in Rumänien (1930-1940): Demokratie im autoritären Umfeld, R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich, 1997, p.323-324. ISBN 3-486-56329-7

- ↑ Boia, p.66-67

- ↑ Valentin Săndulescu, "La puesta en escena del martirio: La vida política de dos cadáveres. El entierro de los líderes rumanos legionarios Ion Moţa y Vasile Marin en febrero de 1937", in Jesús Casquete, Rafael Cruz (eds.), Políticas de la muerte. Usos y abusos del ritual fúnebre en la Europa del siglo XX, Catarata, Madrid, 2009, p.260, 264. ISBN 978-84-8319-418-8

- ↑ (Romanian) N. Batzaria, "Ardeleni şi Macedoneni", in Familia, Nr. 1/1941, p.19-23 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 (Romanian) Marieta Popescu, "Note. Regina din Insula Piticilor", in Familia, Nr. 1/1941, p.103-104 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ (Romanian) Marieta Popescu, "Revista revistelor. Calendarul Universul Copiilor 1941", in Familia, Nr. 1/1941, p.112 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ Batzaria (1942), passim

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Zbuchea (1999), p.219-220

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 (Romanian) Cristina Diac, "Comunism - Avem crime! Vrem criminali!", in Jurnalul Naţional, April 11, 2006

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Lucian Vasile, "Tudorică şi Andrei, eroi ai propagandei de război", in Magazin Istoric, March 2011, p.80-82

- ↑ Victor Frunză, Istoria stalinismului în România, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1990, p.251. ISBN 973-28-0177-8

- ↑ Boia, p.264

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 (Romanian) Nicolae Dima, Constantin Mătasă, "Viaţa neobişnuită a unui om de ştiinţă român refugiat în Statele Unite", in the Canadian Association of Romanian Writers Destine Literare, Nr. 8-9 (16-17), January–February 2011, p.71

- ↑ Boia, p.312; Eugenio Coşeriu, Johannes Kabatek, Adolfo Murguía, »Die Sachen sagen, wie sie sind...«. Eugenio Coşeriu im Gespräch, Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen, 1997, p.11. ISBN 3-8233-5178-8; Zbuchea (1999), p.79

- ↑ Petcu, p.59

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 Karpat, p.565

- ↑ (Romanian) Roxana Vintilă, "Un Jean Moscopol al literaturii", in Jurnalul Naţional, June 17, 2009

- ↑ Adrian Solomon, "The Truth About Romania's Children", in the Romanian Cultural Institute's Plural Magazine, Nr. 30/2007

- ↑ Karpat, p.565, 569

- ↑ (Romanian) Felix Aderca, "O zi la Braşov. Note de drum'", in Contimporanul, Nr. 43/1923, p.3 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- ↑ Karpat, p.584

- ↑ Karpat, p.578, 584

- ↑ Karpat, p.568, 573-576

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 Karpat, p.572

- ↑ Karpat, p.578-580

- ↑ Karpat, p.580

- ↑ Karpat, p.581-584

- ↑ Karpat, p.583-584

- ↑ Zbuchea (1999), p.219

- ↑ (Romanian) Barbu Cioculescu, "Şi fiii de profesori", in Litere, Nr. 10-11/2011, p.8

- ↑ (Romanian) Avram Croitoru, Mioara Cremene, " 'N-am scris totdeauna ce am crezut, dar niciodată ce n-am crezut' ", in Realitatea Evreiască, Nr. 242-243 (1042-1043), December 2005, p.6

- ↑ (Romanian) György Györfi-Deák, "Cu ochii copiilor, pentru bucuria lor", in Caiete Silvane, June 2009

- ↑ Iuteş, in Batzaria (1987), p.3-4

- ↑ (Romanian) Daniel Cristea-Enache, "Elegii de când era mai tânăr (II)", in România Literară, Nr. 19/2006

- ↑ (Romanian) Ioan Holban, "Poezia Anei Blandiana", in Convorbiri Literare, July 2005

- ↑ (Romanian) Gabriela Adameşteanu, "Un monument friabil (II)", in Revista 22, Nr. 789, April 2005

- ↑ (Romanian) Marius Chivu, "DGLR faţă cu receptarea critică", in România Literară, Nr. 41/2005

- ↑ (Romanian) "Nominalizările pentru Premiile A.E.R", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 169, May 2003

- ↑ (Romanian) Andrei Milca, "Studii de morfologie şi un... manual de aromână", in Cronica Română, March 10, 2006

- ↑ (Romanian) Grete Tartler, "Diurna şi nocturna", in România Literară, Nr. 32/2007

References

- Nicolae Batzaria,

- (Romanian) "Profesorul N. Iorga. Impresii şi amintiri", in Familia, Nr. 11-12/1942, p. 37-42 (digitized by the Babeş-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- Poveşti de aur (with a foreword by Gica Iuteş), Editura Ion Creangă, Bucharest, 1987. OCLC 64564234

- Lucian Boia, Capcanele istoriei. Elita intelectuală românească între 1930 şi 1950, Humanitas, Bucharest, 2012. ISBN 978-973-50-3533-4

- M. Şükrü Hanioğlu, Preparation for a Revolution: the Young Turks, 1902-1908, Oxford University Press US, New York City, 2000. ISBN 0-19-513463-X

- (Romanian) Gică Gică, "Ziare şi reviste aromâne la sfârşitul secolului XIX şi începutul secolului XX", in the Tulcea County Aromanian Association Daina, Nr. 4-5/2006, p. 4-8

- Kemal H. Karpat, "The Memoirs of N. Batzaria: The Young Turks and Nationalism", in Studies on Ottoman Social and Political History, Brill Publishers, Leiden, Boston & Cologne, 2002, p. 556-585. ISBN 90-04-12101-3

- (Romanian) Laura Muşeţeanu (ed.), Bibliografie radiofonică românească. Vol. I: 1928-1935, Romanian Radio Broadcasting Company & Editura Casa Radio, Bucharest, 1998. ISBN 973-98662-2-0

- (Romanian) Marian Petcu, "Întâmplări cu ziarişti morţi şi răniţi. O istorie a agresiunilor din presă", in the University of Bucharest Faculty of Journalism Revista Română de Jurnalism şi Comunicare, Nr. 1/2007, p. 58-62

- (Romanian) Gheorghe Zbuchea, O istorie a românilor din Peninsula Balcanică, Editura Biblioteca Bucureştilor, Bucharest, 1999. ISBN 973-98918-8-8

External links

- Film samples (Haplea included) at the National Film Archive of Romania

|