Newtonian dynamics

In physics, the Newtonian dynamics is understood as the dynamics of a particle or a small body according to Newton's laws of motion.

Mathematical generalizations

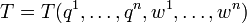

Typically, the Newtonian dynamics occurs in a three-dimensional Euclidean space, which is flat. However, in mathematics Newton's laws of motion can be generalized to multidimensional and curved spaces. Often the term Newtonian dynamics is narrowed to Newton's second law  .

.

Newton's second law in a multidimensional space

Let's consider  particles with masses

particles with masses  in the regular three-dimensional Euclidean space. Let

in the regular three-dimensional Euclidean space. Let  be their radius-vectors in some inertial coordinate system. Then the motion of these particles is governed by Newton's second law applied to each of them

be their radius-vectors in some inertial coordinate system. Then the motion of these particles is governed by Newton's second law applied to each of them

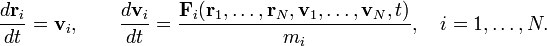

-

(1)

The three-dimensional radius-vectors  can be built into a single

can be built into a single  -dimensional radius-vector. Similarly, three-dimensional velocity vectors

-dimensional radius-vector. Similarly, three-dimensional velocity vectors  can be built into a single

can be built into a single  -dimensional velocity vector:

-dimensional velocity vector:

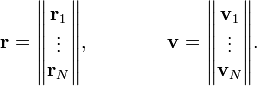

-

(2)

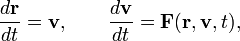

In terms of the multidimensional vectors (2) the equations (1) are written as

-

(3)

i. e they take the form of Newton's second law applied to a single particle with the unit mass  .

.

Definition. The equations (3) are called the

equations of a Newtonian dynamical system in a flat multidimensional Euclidean space, which is called the configuration space of this system. Its points are marked by the radius-vector

. The space whose points are marked by the pair of vectors

. The space whose points are marked by the pair of vectors  is called the phase space of the dynamical system (3).

is called the phase space of the dynamical system (3).

Euclidean structure

The configuration space and the phase space of the dynamical system (3) both are Euclidean spaces, i. e. they are equipped with a Euclidean structure. The

Euclidean structure of them is defined so that the kinetic energy of the single multidimensional particle with the unit mass  is equal to the sum of kinetic energies of the three-dimensional particles with the masses

is equal to the sum of kinetic energies of the three-dimensional particles with the masses  :

:

-

.

.(4)

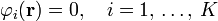

Constraints and internal coordinates

In some cases the motion of the particles with the masses  can be constrained. Typical constraints look like scalar equations of the form

can be constrained. Typical constraints look like scalar equations of the form

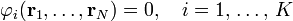

-

.

.(5)

Constraints of the form (5) are called holonomic and scleronomic. In terms of the radius-vector  of the Newtonian dynamical system (3) they are written as

of the Newtonian dynamical system (3) they are written as

-

.

.(6)

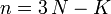

Each such constraint reduces by one the number of degrees of freedom of the Newtonian dynamical system (3). Therefore the constrained system has  degrees of freedom.

degrees of freedom.

Definition. The constraint equations (6) define an  -dimensional manifold

-dimensional manifold  within the configuration space of the Newtonian dynamical system (3). This manifold

within the configuration space of the Newtonian dynamical system (3). This manifold  is called the configuration space of the constrained system. Its tangent bundle

is called the configuration space of the constrained system. Its tangent bundle  is called the phase space of the constrained system.

is called the phase space of the constrained system.

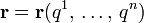

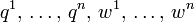

Let  be the internal coordinates of a point of

be the internal coordinates of a point of  . Their usage is typical for the Lagrangian mechanics. The radius-vector

. Their usage is typical for the Lagrangian mechanics. The radius-vector  is expressed as some definite function of

is expressed as some definite function of  :

:

-

.

.(7)

The vector-function (7) resolves the constraint equations (6) in the sense that upon substituting (7) into (6) the equations (6) are fulfilled identically in  .

.

Internal presentation of the velocity vector

The velocity vector of the constrained Newtonian dynamical system is expressed in terms of the partial derivatives of the vector-function (7):

-

.

.(8)

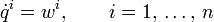

The quantities  are called internal components of the velocity vector. Sometimes they are denoted with the use of a separate symbol

are called internal components of the velocity vector. Sometimes they are denoted with the use of a separate symbol

-

(9)

and then treated as independent variables. The quantities

-

(10)

are used as internal coordinates of a point of the phase space  of the constrained Newtonian dynamical system.

of the constrained Newtonian dynamical system.

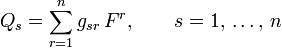

Embedding and the induced Riemannian metric

Geometrically, the vector-function (7) implements an embedding of the configuration space  of the constrained Newtonian dynamical system into the

of the constrained Newtonian dynamical system into the  -dimensional flat comfiguration space of the unconstrained

Newtonian dynamical system (3). Due to this embedding the Euclidean structure of the ambient space induces the Riemannian metric onto the manifold

-dimensional flat comfiguration space of the unconstrained

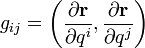

Newtonian dynamical system (3). Due to this embedding the Euclidean structure of the ambient space induces the Riemannian metric onto the manifold  . The components of the metric tensor of this induced metric are given by the formula

. The components of the metric tensor of this induced metric are given by the formula

-

,

,(11)

where  is the scalar product associated with the Euclidean structure (4).

is the scalar product associated with the Euclidean structure (4).

Kinetic energy of a constrained Newtonian dynamical system

Since the Euclidean structure of an unconstrained system of  particles is entroduced through their kinetic energy, the induced Riemannian structure on the configuration space

particles is entroduced through their kinetic energy, the induced Riemannian structure on the configuration space  of a constrained system preserves this relation to the kinetic energy:

of a constrained system preserves this relation to the kinetic energy:

-

.

.(12)

The formula (12) is derived by substituting (8) into (4) and taking into account (11).

Constraint forces

For a constrained Newtonian dynamical system the constraints described by the equations (6) are usually implemented by some mechanical framework. This framework produces some auxiliary forces including the force that maintains the system within its configuration manifold  . Such a maintaining force is perpendicular to

. Such a maintaining force is perpendicular to  . It is called the normal force. The force

. It is called the normal force. The force  from (6) is subdivided into two components

from (6) is subdivided into two components

-

.

.(13)

The first component in (13) is tangent to the configuration manifold  . The second component is perpendicular to

. The second component is perpendicular to  . In coincides with the normal force

. In coincides with the normal force  .

.

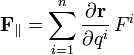

Like the velocity vector (8), the tangent force

has its internal presentation

has its internal presentation

-

.

.(14)

The quantities  in (14) are called the internal components of the force vector.

in (14) are called the internal components of the force vector.

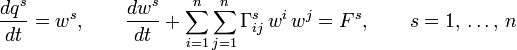

Newton's second law in a curved space

The Newtonian dynamical system (3) constrained to the configuration manifold  by the constraint equations (6) is described by the differential equations

by the constraint equations (6) is described by the differential equations

-

,

,(15)

where  are Christoffel symbols of the metric connection produced by the Riemannian metric (11).

are Christoffel symbols of the metric connection produced by the Riemannian metric (11).

Relation to Lagrange equations

Mechanical systems with constraints are usually described by Lagrange equations:

-

,

,(16)

where  is the kinetic energy the constrained dynamical system given by the formula (12). The quantities

is the kinetic energy the constrained dynamical system given by the formula (12). The quantities  in

(16) are the inner covariant components of the tangent force vector

in

(16) are the inner covariant components of the tangent force vector  (see (13) and (14)). They are produced from the inner contravariant components

(see (13) and (14)). They are produced from the inner contravariant components  of the vector

of the vector  by means of the standard index lowering procedure using the metric (11):

by means of the standard index lowering procedure using the metric (11):

-

,

,(17)

The equations (16) are equivalent to the equations (15). However, the metric (11) and

other geometric features of the configuration manifold  are not explicit in (16). The metric (11) can be recovered from the kinetic energy

are not explicit in (16). The metric (11) can be recovered from the kinetic energy  by means of the formula

by means of the formula

-

.

.(18)