Nestorian Stele

The Nestorian Stele (also known as the Nestorian Stone, Nestorian Monument,[1] or Nestorian Tablet) is a Tang Chinese stele erected in 781 that documents 150 years of early Christianity in China.[2] It is a 279 cm tall limestone block with text in both Chinese and Syriac describing the existence of Christian communities in several cities in northern China. It reveals that the initial Nestorian Christian church had met recognition by the Tang Emperor Taizong, due to efforts of the Christian missionary Alopen in 635.[3] Buried in 845, probably during religious suppression, the stele was not rediscovered until 1625.

Content of the inscription

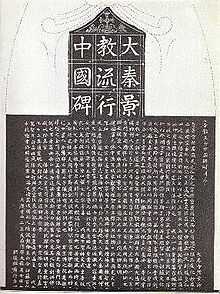

The heading on the stone, which is in Chinese, means Memorial of the Propagation in China of the Luminous Religion from Daqin (大秦景教流行中國碑; pinyin: Dàqín Jǐngjiào liúxíng Zhōngguó bēi, abbreviated 大秦景教碑). An even more abbreviated version of the title, 景教碑 (Jǐngjiào bēi, "The Stele of the Luminous Religion"), in its Wade-Giles form, Ching-chiao-pei or Chingchiaopei, was used by some Western writers to refer to the stele as well.[4]

The name of the stele can also be translated as A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Chin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom (the church referred to itself as "The Luminous Religion of Daqin", Daqin being the Chinese language term for the Roman Empire in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD,[5] and in later eras also used to refer to the Syriac Christian churches).[6] The stele was erected on January 7, 781, at the imperial capital city of Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an), or at nearby Chou-Chih (盩厔; Pinyin Zhouzhi). The calligraphy was by Lü Xiuyan (呂秀巖), and the content was composed by the Nestorian monk Jingjing in the four- and six-character euphemistic style. A gloss in Syriac identifies Jingjing with "Adam, priest, chorepiscopus and papash of Sinistan" (Adam qshisha w'kurapisqupa w'papash d'Sinistan). Although the term papash (literally "pope") is unusual and the normal Syriac name for China is Beth Sinaye, not Sinistan, there is no reason to doubt that Adam was the metropolitan of the Nestorian ecclesiastical province of Beth Sinaye, created a half-century earlier during the reign of the patriarch Sliba-zkha (714–28). A Syriac dating formula refers to the Nestorian patriarch Hnanishoʿ II (773–80), news of whose death several months earlier had evidently not yet reached the Nestorians of Chang'an. In fact, the reigning Nestorian patriarch in January 781 was Timothy I (780–823), who had been consecrated in Baghdad on 7 May 780.[7] The names of several higher clergy (one bishop, two chorepiscopi and two archdeacons) and around seventy monks or priests are listed.[8] The names of the higher clergy appear on the front of the stone, while those of the priests and monks are inscribed in rows along the narrow sides of the stone, in both Syriac and Chinese. In some cases, the Chinese names are phonetically close to the Syriac originals, but in many other cases, they bear little resemblance to them. Some of the Nestorian monks had distinctive Persian names (e.g. Isadsafas, Gushnasap), suggesting that they might have come from Fars or elsewhere in Persia, but most of them had commonplace Christian names or the kind of compound Syriac name (e.g. ʿAbdishoʿ, 'servant of Jesus') much in vogue among all Nestorian Christians. In such cases, it is impossible to guess at their place of origin.

On top of the tablet, there is a cross. Below this headpiece there is a long Chinese inscription, consisting of around 1,900 Chinese characters, which is glossed occasionally in Syriac (several sentences, amounting to about 50 Syriac words). Calling God "Veritable Majesty", the text refers to Genesis, the cross, and the baptism. It also pays tribute to missionaries and benefactors of the church, who are known to have arrived in China by 640. The text contains the name of an early missionary, Alopen. The tablet describes the "Illustrious Religion", emphasizing the Trinity and the Incarnation, but there is nothing about Christ's crucifixion or resurrection. Other Chinese elements referred to include a wooden bell, beard, tonsure, and renunciation.[2] The Syriac proper names for God, Christ and Satan (Allaha, Mshiha and Satana) were rendered phonetically into Chinese. Chinese transliterations were also made of one or two words of Sanskrit origin, such as Sphatica and Dasa. There is also a Persian word denoting Sunday.[9]

Discovery of the stele

The stele is thought to have been buried in 845, during a campaign of anti-Buddhist persecution, which also affected the Nestorians.[10]

The stele was unearthed in the late Ming Dynasty (between 1623 and 1625) beside Chongren Temple (崇仁寺).[11] According to the account by the Jesuit Alvaro Semedo, the workers who found the stele immediately reported the find to the governor, who soon visited the monument, and had it installed on a pedestal, under a protective roof, requesting the nearby Buddhist monastery to care for it.[12] The newly discovered stele attracted attention of local intellectuals. It was Zhang Gengyou (Wade-Giles: Chang Keng-yu) who first identified the text as Christian in content. Zhang, who had been aware of Christianity through Matteo Ricci, and who himself may have been Christian, sent a copy of the stele's Chinese text to his Christian friend, Leon Li Zhizao in Hangzhou, who in his turn published the text and told about it to the locally based Jesuits.[12]

Alvaro Semedo was the first European to visit the stele (some time between 1625 and 1628).[13] Nicolas Trigault's Latin translation of the monument's inscription soon made its way in Europe, and was apparently first published in a French translation, in 1628. Portuguese and Italian translations, and a Latin re-translation, were soon published as well. Semedo's account of the monument's discovery was published in 1641, in his Imperio de la China.[14]

Early Jesuits attempted to claim that the stele was erected by a historical community of Roman Catholics in China and called Nestorianism a heresy and claimed that it was Catholics who first brought Christianity to China, but later historians and writers admitted that it was indeed Nestorian, not Catholic.[15]

The first publication of the original Chinese and Syriac text of the inscription in Europe is attributed to Athanasius Kircher. China Illustrata edited by Kircher (1667) included a reproduction of the original inscription in Chinese characters,[16] Romanization of the text, and a Latin translation.[17] This was perhaps the first sizeable Chinese text made available in its original form to the European public. A sophisticated Romanization system, reflecting Chinese tones, used to transcribe the text, was the one developed earlier by Matteo Ricci's collaborator Lazzaro Cattaneo (1560–1640).

The work of the transcription and translation was carried out by Michał Boym and two young Chinese Christians who visited Rome in the 1650s and 1660s: Boym's traveling companion Andreas Zheng (Chinese: 郑安德勒; pinyin: Zhèng Āndélè, Wade-Giles: Cheng An-to-le) and, later, another person who signed in Latin as "Matthaeus Sina". D.E. Mungello suggests that "Matthaeus Sina" may have been the person who traveled from China to Europe overland with Johann Grueber.[18]

Debate about the stele

The Nestorian Stone has attracted the attention of some anti-Christian, Christian anti-Catholic, or Catholic anti-Jesuit groups in the 17th century, who have argued that the stone is a fake or that the inscriptions were modified by the Jesuits who served in the Ming Court. The three most prominent early skeptics were the German-Dutch Presbyterian scholar Georg Horn (born 1620) (De originibus Americanis, 1652), the German historian Gottlieb Spitzel (1639–1691) (De re literaria Sinensium commentarius, 1660), and the Dominican missionary Domingo Navarrete (1618–1686) (Tratados historicos, politicos, ethicos, y religiosos de la monarchia de China, 1676). Later, Navarrete's point of view was picked by French Jansenists and Voltaire.[19]

By the 19th century, the debate had become less sectarian and more scholarly. Notable skeptics include Karl Friedrich Neumann, Stanislas Julien, Edward E. Salisbury and Charles Wall.[14][20] Ernest Renan initially had "grave doubts", but eventually changed his mind in the light of later scholarship, in favor of the stele's genuineness.[21] The defenders included some non-Jesuit scholars, such as Alexander Wylie, James Legge, and Jean-Pierre-Guillaume Pauthier, although the most substantive work in defense of the stele's authenticty – the three-volume La stèle chrétienne de Si-ngan-fou (1895 to 1902) was authored by the Jesuit scholar Henri Havret (1848–1902).[14]

Paul Pelliot (1878–1945) did an extensive amount of research on the stele, which, however, was only published posthumously, in 1996.[22][23] His and Havret's works are still regarded as the two "standard books" on the subject.[24]

In the assessment of modern scholars (e.g., David E. Mungello), there is no scientific or historical evidence to support the claims of the non-authenticity of the stele. Both of Navarrete's main arguments – the absence of references in Chinese records to the events described on the stele, and the supposed widespread skepticism in 17th century China about the authenticity of the monument – appear to be mistaken.[19]

The attitude of Western scholars to the stele has also attracted criticism, one author saying that "when Westerners discussed the Nestorian monument they were not really talking about China at all. The stone served as a kind of screen onto which they could project their own self-image and this is what they were looking at, not China. The stone came to represent the empire and its history for many Western readers, but only because it was seen as a tiny bit of the West that was already there."[25] Similarly, some polemicists' skepticism about the stele was not a reflection of the views of Chinese themselves, but "far more a European phenomenon which sprang from sectarian rather than scholarly grounds."[19]

Other early Christian monuments in China

Numerous Christian gravestones have also been found in China in the Xinjiang region, Quanzhou and elsewhere from a somewhat later period. There are also two much later stelae (from 960 and 1365) presenting a curious mix of Christian and Buddhist aspects, which are preserved at the site of the former Monastery of the cross in the Fangshan District, near Beijing.[26]

Modern location, and replicas

Since the late 19th century a number of European scholars opined in favor of somehow getting the stele out of China and into the British Museum or some other "suitable" location (e.g., Frederic H. Balfour in his letter published in The Times in early 1886[27]). Their plans, however, were frustrated. When the Danish scholar and adventurer Frits Holm came to Xi'an in 1907 with the plans to take the monument to Europe,[28] the local authorities intervened, and moved the stele, complete with its tortoise, from its location near Chongren Temple[11][29] to Xi'an's Beilin Museum (Forest of Steles Museum).[28][30]

The disappointed Holm had to be satisfied with having an exact copy of the stele made for him. Instead of London's British Museum, he had the replica stele shipped to New York, planning to sell it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The museum's director Caspar Purdon Clarke, however, was less than enthusiastic about purchasing "so large a stone ... of no artistic value". Nonetheless, the replica stele was exhibited in the museum ("on loan" from Mr. Holm) for about 10 years.[28] Eventually, in 1917 some Mr. George Leary, a wealthy New Yorker, purchased the replica stele and sent it to Rome, as a gift to the Pope.[31] A full-sized replica cast from that replica is on permanent display in the Bunn Intercultural Center on the campus of Georgetown University (Washington, DC).

The original Nestorian Stele remains in the Forest of Steles. It is now exhibited in the museum's Room Number 2, and is the first stele on the left after the entry. When the official list of Chinese cultural relics forbidden to be exhibited abroad was promulgated in 2003, the stele was included into this short list of particularly valuable and important items.

A copy of the stele and its tortoise have been installed near Xi'an Daqin Pagoda as well.[32]

Another copy of the stele exists in Japan, installed on Mount Kōya.[33]

See also

- Jesus Sutra

References

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844 now in the public domain in the United States.

- ↑ Saeki, Yoshiro (1928) [1916]. The Nestorian monument in China. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hill, Henry, ed (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto, Canada. pp. 108–109

- ↑ Jenkins, Peter (2008). The Lost History of Christianity: the Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia - and How It Died. New York: Harper Collins. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-06-147280-0.

- ↑ E.g. Holm 2001

- ↑ Hill, John E. (2004). "The Kingdom of Da Qin". The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu (2nd ed.). Retrieved 2008-11-30.

- ↑ Foster, John (1939). The Church in T'ang Dynasty. Great Britain: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 123.

- ↑ Eliya of Nisibis, Chronography (ed. Brooks), i. 32 and 87

- ↑ Stewart, John (1928). Nestorian missionary enterprise, the story of a church on fire. Edinburgh, T. & T. Clark., p. 183.

- ↑ Saeki, pp. 14–15

- ↑ Mungello, David E. (1989). Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology. University of Hawaii Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-8248-1219-0.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Saeki, P.Y. (1951). Nestorian Documents and Relics in China (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Maruzen.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mungello, p. 168

- ↑ Mungello (p. 168), following Legge, is inclined to date Semedo's visit to Xi'an to 1628, but also mentions that some researchers interpret Semedo's account as to mean a 1625 visit.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Mungello, p. 169

- ↑ The Chinese repository, Volume 13. VICTORIA, HONGKONG: Printed for the proprietors. 1844. p. 472. Retrieved 2011-05-08.(Original from Harvard University)

- ↑ Reproduction of the original Chinese and Syriac text in Kircher's China Illustrata

- ↑ China monumentis: qua sacris quà profanis, ..., pp. 13-28. An English translation of Kircher's work can be found as an "Appendix" in: Johan Nieuhof, An embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, emperor of China : delivered by their excellencies Peter de Goyer and Jacob de Keyzer, at his imperial city of Peking wherein the cities, towns, villages, ports, rivers, &c. in their passages from Canton to Peking are ingeniously described by John Nieuhoff ; also an epistle of Father John Adams, their antagonist, concerning the whole negotiation ; with an appendix of several remarks taken out of Father Athanasius Kircher ; Englished and set forth with their several sculptures by John Ogilby (1673); the relevant chapters appear there as "[Kircher Appendix] Chap. 2 and 3", pp. 323-339.

- ↑ Mungello, p. 167

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Mungello, p. 170-171

- ↑ Wall, Charles (1840). An examination of the ancient orthography of the Jews, and of the original state of the text of the Hebrew Bible. Whittaker and Co. pp. 159–245.

- ↑ Keevak 2008, p. 103

- ↑ Sinologists: Paul Pelliot

- ↑ Paul Pelliott, "L'inscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-fou", ed. avec supléments par Antonino Forte, Kyoto et Paris, 1996. ISBN 4-900793-12-4

- ↑ Keevak 2008, p. 4

- ↑ Keevak, Michael (2008), The Story of a Stele: China's Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916, ISBN 962-209-895-9

- ↑ Moule, A. C. (1930). Christians in China before the year 1550. London: SPCK. pp. 86−89.

- ↑ Henri Havret (1895), p.4

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Keevak 2008, pp. 117–121. Holm's original report can be found in Carus, Wylie & Holm 1909, and also in more popular form in Holm 2001

- ↑ Keevak 2008, p. 27

- ↑ See modern photos of the stele on Flickr.com, complete with the same tortoise

- ↑ NEW CAPTAIN ON ST. LOUIS.; Hartley, Young American Line Commander, Praised for Handling Ship. The New York Times, January 29, 1917

- ↑ Photos of the replica stele outside of the Daqin Pagoda

- ↑ Keevak 2008, p. 125

Further reading

- Henri Havret sj, La stèle chrétienne de Si Ngan-fou, Parts 1-3. Full text (was) available at Gallica:

Some of the volumes can also be found on archive.org.

- Carus, Paul; Wylie, Alexander; Holm, Frits (1909), The Nestorian Monument: An Ancient Record of Christianity in China, with Special Reference to the expedition of Frits V. Holm..., The Open court publishing company

- Holm, Frits (2001), My Nestorian Adventure in China: A Popular Account of the Holm-Nestorian Expedition to Sian-Fu and Its Results, Volume 6 of Georgias reprint series, Gorgias Press LLC, ISBN 0-9713097-6-0. Originally published by: Hutchinson & Co, London, 1924.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nestorian Stele. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- stele text in English from researchers at Fordham University; actually 1919 translation of C. Horne

- Large photograph of a rubbing of the stele from University of Birmingham (scroll to bottom of page)

- "The Jesus Messiah of Xi'an" ― translation and exposition of doctrinal passages in the stele text. From B. Vermander (ed.), Le Christ Chinois, Héritages et espérance (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1998).

- Photos of a replica of the Nestorian Stele in Xi-an; photos are of a replica located in Japan Japanese text.

- SIR E. A. WALLIS BUDGE, KT., THE MONKS OF KUBLAl KHAN EMPEROR OF CHINA (1928) - contains reproductions of early photographs of the stele where it stood in the early 20th century (from Havret etc.)

- Nestorian Stele – Inscription: A slice of Christian history from China. Australian Museum.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||