Near-Earth object

A near-Earth object (NEO) is a Solar System object whose orbit brings it into proximity with Earth. All NEOs have a closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) of less than 1.3 AU.[2] They include a few thousand near-Earth asteroids (NEAs), near-Earth comets, a number of solar-orbiting spacecraft, and meteoroids large enough to be tracked in space before striking the Earth. It is now widely accepted that collisions in the past have had a significant role in shaping the geological and biological history of the planet.[3] NEOs have become of increased interest since the 1980s because of increased awareness of the potential danger some of the asteroids or comets pose to the Earth, and active mitigations are being researched.[4]

Those NEOs that are asteroids (NEA) have orbits that lie partly between 0.983 and 1.3 astronomical units away from the Sun.[5] When an NEA is detected it is submitted to the IAU's Minor Planet Center (located at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) for cataloging. Some near-Earth asteroids' orbits intersect that of Earth's so they pose a collision danger.[6] The United States, European Union, and other nations are currently scanning for NEOs[7] in an effort called Spaceguard.

In the United States, NASA has a congressional mandate to catalogue all NEOs that are at least 1 kilometer wide, as the impact of such an object would be catastrophic. As of August 2012, there had been 848 near-Earth asteroids larger than 1 km discovered, of which 154 are potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs).[8] It was estimated in 2006 that 20% of the mandated objects have not yet been found.[7] As a result of NEOWISE in 2011, it is estimated that 93% of the NEAs larger than 1 km have been found and that only about 70 remain to be discovered.[9]

Potentially hazardous objects (PHOs) are currently defined based on parameters that measure the object's potential to make threatening close approaches to the Earth.[10] Mostly objects with an Earth minimum orbit intersection distance (MOID) of 0.05 AU or less and an absolute magnitude (H) of 22.0 or brighter (a rough indicator of large size) are considered PHOs. Objects that cannot approach closer to the Earth (i.e. MOID) than 0.05 AU (7,500,000 km; 4,600,000 mi), or are smaller than about 150 m (500 ft) in diameter (i.e. H = 22.0 with assumed albedo of 13%), are not considered PHOs.[2] The NASA Near Earth Object Catalog also includes the approach distances of asteroids and comets measured in lunar distances,[11] and this usage has become a common unit of measure used by the news media in discussing these objects.

Some NEOs are of high interest because they can be physically explored with lower mission velocity even than the Moon, due to their combination of low velocity with respect to Earth (ΔV) and small gravity, so they may present interesting scientific opportunities both for direct geochemical and astronomical investigation, and as potentially economical sources of extraterrestrial materials for human exploitation.[12] This makes them an attractive target for exploration.[13] As of 2012, three near-Earth objects have been visited by spacecraft: 433 Eros, by NASA's Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous probe,[14] 25143 Itokawa, by the JAXA Hayabusa mission,[15] and 4179 Toutatis, by CNSA's Chang'e 2 spacecraft.[4][16]

History of human awareness of NEOs

Human perception of near-Earth objects as benign objects of fascination or killer objects with high risk to human society have ebbed and flowed in the short period of human history that NEOS have been scientifically observed.[17]

Risk

More recently, a typical frame of reference for looking at NEOs has been through the scientific concept of risk. In this frame, the risk that any near-Earth object poses is typically seen through a lens that is a function of both the culture and the technology of human society. "NEOs have been understood differently throughout history." Each time an NEO is observed, "a different risk was posed, and throughout time that risk perception has evolved. It is not just a matter of scientific knowledge."[18]

Such perception of risk is thus "a product of religious belief, philosophic principles, scientific understanding, technological capabilities, and even economical resourcefulness."[18]

Risk scales

There are two schemes for the scientific classification of impact hazards from NEOs:

- the simple Torino Scale, and

- the more complex Palermo Technical Impact Hazard Scale

The annual background frequency used in the Palermo scale for impacts of energy greater than E megatonnes is estimated as:[19]

For instance, this formula implies that the expected value of the time from now until the next impact greater than 1 megatonne is 33 years, and that when it occurs, there is a 50% chance that it will be above 2.4 megatonnes. This formula is only valid over a certain range of E.

However, another paper[20] published in 2002 – the same year as the paper on which the Palermo scale is based – found a power law with different constants:

This formula gives considerably lower rates for a given E. For instance, it gives the rate for bolides of 10 megatonnes or more (like the Tunguska explosion) as 1 per thousand years, rather than 1 per 210 years as in the Palermo formula. However, the authors give a rather large uncertainty (once in 400 to 1800 years for 10 megatonnes), due in part to uncertainties in determining the energies of the atmospheric impacts that they used in their determination.

Highly rated risks

On 24 December 2004, minor planet 99942 Apophis (at the time known by its provisional designation 2004 MN4) was assigned a 4 on the Torino scale, the highest rating ever achieved. There was a 2.7% chance of Earth impact on 13 April 2029. However, on 28 December 2004, the risk of impact dropped to zero for 2029, but future potential impact solutions were still rated 1 on the Torino scale. The 2036 risk was lowered to a Torino rating of 0 in August 2006. The Palermo rating is −3.2.[21]

The only known NEO with a Palermo scale value currently greater than zero is (29075) 1950 DA, which may pass very close to or collide with the Earth (probability ≤ 0.003) in the year 2880. Depending on the unknown orientation of its axis of rotation, it will either miss the Earth by tens of millions of kilometers, or have a 1 in 300 chance of hitting the Earth. However, humanity has over 800 years to refine the orbit of (29075) 1950 DA, and to deflect it, if necessary.[22]

List of current threats

NASA maintains a continuously updated Sentry Risk Table of the most significant NEO threats in the next 100 years.[21] All or nearly all of the objects are highly likely to eventually drop off the list as more observations come in, reducing the uncertainties and enabling more accurate orbital predictions. (The list does not include 1950 DA, because that will not strike for at least 800 years.)[4][22]

History of NEO science and exploratory mission proposals

In a 2013 article in Wired Science, David Portree provides an overview of NEO science and proposed asteroidal missions, with an emphasis on the outcome of two conferences held in the 1970s. The International Astronomical Union minor planets workshop was held in Tucson, Arizona in March 1971 and a consensus "emerged that launching spacecraft to asteroids would be 'premature'."[17] "In January 1978, NASA’s Office of Space Science held a workshop at the University of Chicago to "assess the state of asteroid studies and consider options for the future."[17]

Of all of the near-Earth asteroids (NEA) that had been discovered by mid-1977, it was estimated that spacecraft could rendezvous with and return from only about one in 10 using less propulsive energy than is necessary to reach Mars. "Because even the most massive NEA—35 kilometres (22 mi)-wide 1036 Ganymed, discovered in 1924, has a very low surface gravity—landing and takeoff would need very little energy. This meant that a single spacecraft could sample multiple sites on any given NEA."[17] Overall, it was estimated that about one percent of all NEAs might provide opportunities for human-crewed missions, or no more than about ten known NEAs. Therefore, unless the NEA discovery rate were "immediately increased five-fold, no opportunity to launch 'astronaut-scientists' to an NEA was likely to occur within a decade of the Chicago workshop."[17]

Number and classification of near-Earth objects

| Name/Year | (H) |

|---|---|

| 2008 EJ1 | 15.8 |

| (243298) 2008 EN82 | 15.6 |

| 2011 UL21 | 15.8 |

| 2012 SF51 | 15.4 |

| 2012 US136 | 15.9 |

| 2013 GJ35 | 15.8 |

| 2013 UQ4 | 12.8 |

Near-Earth objects are classified as meteoroids, asteroids, or comets depending on size and composition. Asteroids can also be members of an asteroid family, and comets create meteoroid streams that can generate meteor showers.

As of February 2013, 9,683 NEOs have been discovered:[8] 93 near-Earth comets and 9,590 near-Earth Asteroids. Of those there are 751 Aten asteroids, 3,613 Amor asteroids, and 5,214 Apollo asteroids. There are 1,360 NEOs that are classified as potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs). Currently, 155 PHAs and 861 NEAs have an absolute magnitude of 17.75 or brighter, which roughly corresponds to at least 1 km in size.[8]

As of February 2013, there are 430 NEAs on the Sentry impact risk page at the NASA website.[21] A significant number of these NEAs – 215 as of May 2010 – are equal to or smaller than 50 meters in diameter and none of the listed objects are placed even in the "yellow zone" (Torino Scale 2), meaning that none warrant the attention of general public.[24] As of January 2013, only asteroid 2007 VK184 is listed as having a Torino Scale of 1. The JPL Small-Body Database lists 1,518 near Earth asteroids with an absolute magnitude (H) dimmer than 25 (roughly 50 meters in diameter).[25]

Near-Earth asteroids smaller than ~1 meter are near-Earth meteoroids and are listed as asteroids on most asteroid tables. The smallest known near-Earth meteoroid is 2008 TS26 with an absolute magnitude of 33 and estimated size of only 1 meter.[25]

Near-Earth asteroids

These are objects in a near-Earth orbit without the tail or coma of a comet. As of June 2013, 9,991 near-Earth asteroids are known,[8] ranging in size from 1 meter up to ~32 kilometers (1036 Ganymed). The number of near-Earth asteroids over one kilometer in diameter is estimated to be about 981.[9][26][27] The composition of near-Earth asteroids is comparable to that of asteroids from the asteroid belt, reflecting a variety of asteroid spectral types.[28]

NEAs survive in their orbits for just a few million years.[5] They are eventually eliminated by planetary perturbations, causing ejection from the Solar System or a collision with the Sun or a planet. With orbital lifetimes short compared to the age of the Solar System, new asteroids must be constantly moved into near-Earth orbits to explain the observed asteroids. The accepted origin of these asteroids is that asteroid-belt asteroids are moved into the inner Solar System through orbital resonances with Jupiter. The interaction with Jupiter through the resonance perturbs the asteroid's orbit and it comes into the inner Solar System. The asteroid belt has gaps, known as Kirkwood gaps, where these resonances occur as the asteroids in these resonances have been moved onto other orbits. New asteroids migrate into these resonances, due to the Yarkovsky effect that provides a continuing supply of near-Earth asteroids.[29]

A small number of NEOs are extinct comets that have lost their volatile surface materials, although having a faint or intermittent comet-like tail does not necessarily result in a classification as a near-Earth comet, making the boundaries somewhat fuzzy. The rest of the near-Earth asteroids are driven out of the asteroid belt by gravitational interactions with Jupiter.[5][30]

Near-Earth asteroids are divided into groups based on their semi-major axis (a), perihelion distance (q), and aphelion distance (Q):[2][5]

- The Atiras or Apohele asteroids have orbits strictly inside Earth's orbit: an Atira asteroid's aphelion distance (Q) is smaller than Earth's perihelion distance (0.983 AU). That is, Q < 0.983 AU. (This implies that the asteroid's semi-major axis is also less than 0.983 AU.)

- The Atens have a semi-major axis of less than 1 AU and cross Earth's orbit. Mathematically, a < 1.0 AU and Q > 0.983 AU.

- The Apollos have a semi-major axis of more than 1 AU and cross Earth's orbit. Mathematically, a > 1.0 AU and q < 1.017 AU. (1.017 AU is Earth's aphelion distance.)

- The Amors have orbits strictly outside Earth's orbit: an Amor asteroid's perihelion distance (q) is greater than Earth's aphelion distance (1.017 AU). Amor asteroids are also near-earth objects so q < 1.3 AU. In summary, 1.017 AU < q < 1.3 AU. (This implies that the asteroid's semi-major axis (a) is also larger than 1.017 AU.) Some Amor asteroid orbits cross the orbit of Mars.

(Note: Some authors define the Atens group differently: they define it as being all the asteroids with a semi-major axis of less than 1 AU. That is, they consider the Atiras to be part of the Atens. Historically, until 1998, there were no known or suspected Atiras, so the distinction wasn't necessary.)

Because the Atens and all Apollos have orbits that cross Earth's orbit, they might impact the Earth. Atiras and Amors do not cross the Earth's orbit and are not immediate impact threats, but their orbits may change to become Earth-crossing orbits in the future.

Near-Earth comets

As of February 2013, 93 near-Earth comets have been discovered.[8] Although no impact of a comet in Earth's history has been conclusively confirmed, the Tunguska event may have been caused by a fragment of Comet Encke.[31] Cometary fragmenting may also be responsible for some impacts from near-Earth objects. It is rare for a comet to pass within 0.1 AU (15,000,000 km; 9,300,000 mi) of Earth.[32]

These near-Earth objects were probably derived from the Kuiper belt, beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Impact rate

Stony asteroids with a diameter of 4 meters (13 ft) impact Earth approximately once per year.[33] Asteroids with a diameter of roughly 7 meters enter Earth's atmosphere with as much energy as Little Boy (the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, approximately 15 kilotonnes of TNT) about every 5 years.[33] These ordinarily explode in the upper atmosphere, and most or all of the solids are vaporized.[34] Every 2000–3000 years, objects produce explosions of 10 megatons comparable to the one observed at Tunguska in 1908.[35] Objects with a diameter of one kilometer hit the Earth an average of twice every million year interval.[5] Large collisions with five kilometer objects happen approximately once every twenty million years.[33]

Assuming that these rates will continue for the next billion years, there exist at least 2,000 objects of diameter greater than 1 km that will eventually hit Earth. However, most of these are not yet considered potentially hazardous objects because they are currently orbiting between Mars and Jupiter. Eventually they will change orbits and become NEOs. Objects spend on average a few million years as NEOs before hitting the Sun, being ejected from the Solar System, or (for a small proportion) hitting a planet.[5]

Historic impacts

The general acceptance of the Alvarez hypothesis, explaining the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event as the result of a large object impact event, raised the awareness of the possibility of future Earth impacts with other objects that cross the Earth's orbit.[3]

1908 Tunguska event

It is now highly believed that on 30 June 1908 a stony asteroid exploded over Tunguska with the energy of 10 megatons of TNT. The explosion occurred at a height of 8.5 kilometers. The object that caused the explosion has been estimated to have had a diameter of 45–70 meters.[36]

1930 Brazilian event

On August 13, 1930 the area near Curuçá River at latitude 5° S and longitude 71.5° W experienced a meteoric air burst, also known as the "Brazilian Tunguska event".[37][38]

The mass of the meteorite was estimated at between 1,000 and 25,000 tons, with an energy release estimated between 0.1 and 5 megatons, significantly smaller than the Tunguska Event.[37] [38][39][40]

1979 Vela Incident

On the 22 of September 1979 event recorded as occurring near the junction of the South Atlantic and the Indian Ocean was possibly a low-yield nuclear test, but was also initially thought to have been caused by the possible impact of an extraterrestrial object. The event, which became known as the Vela Incident, was identified by a U.S. Vela defense satellite in Earth orbit. The event alarm triggered multi-year investigations by several organizations which could not conclusively determine if the explosion was of nuclear or non-nuclear origin.

2002 Eastern Mediterranean event

On 6 June 2002 an object with an estimated diameter of 10 meters collided with Earth. The collision occurred over the Mediterranean Sea, between Greece and Libya, at approximately 34°N 21°E and the object exploded in mid-air. The energy released was estimated (from infrasound measurements) to be equivalent to 26 kilotons of TNT, comparable to a small nuclear weapon.[41]

2008 Sudan event

On 6 October 2008, scientists calculated that a small near-Earth asteroid, 2008 TC3, just sighted that night, would impact the Earth on 7 October over Sudan, at 0246 UTC, 5:46 local time.[42][43] The asteroid arrived as predicted.[44][45] This is the first time that an asteroid impact on Earth has been accurately predicted. While hundreds of rock fragments have subsequently been recovered on ground,[46] no reports of the actual impact have so far been published since it occurred in a very sparsely populated area.[47]

2009 Indonesia event

A large fireball was observed in the skies near Bone, Indonesia on October 8, 2009. This was thought to be caused by an asteroid approximately 10 meters in diameter. The fireball contained an estimated energy of 50 kilotons of TNT, or about twice the Nagasaki atomic bomb. No injuries were reported.[48]

2013 Chelyabinsk meteor

On 15 February 2013, an Apollo asteroid entered Earth's atmosphere over Russia at about 09:20 YEKT (03:20 UTC)[49][50][51][52] with an estimated speed of 18 km/s (40,000 mph);[49] it became a brilliant superbolide meteor over the southern Ural region.[53] The dazzling light of the meteor was bright enough to cast moving shadows during the morning daylight in Chelyabinsk and was observed from Sverdlovsk, Tyumen, Orenburg Oblasts, the Republic of Bashkortostan, and in Kazakhstan. Eyewitnesses also felt intense heat from the fireball.[54]

The object exploded in an air burst over Chelyabinsk Oblast at a height of about 15 to 25 km (9.3 to 15.5 mi),[49][55] with 23.3 km (14.5 mi) being the most recent official burst height.[56] It exploded with the generation of a bright flash, small fragmentary meteorites and a powerful shock wave. The atmosphere absorbed most of the object's energy,[57] with a total kinetic energy before atmospheric impact equivalent to ~ 440 kilotons of TNT (~ 1.8 PJ),.[49][56][58][59] This is about 20–30 times more energy than was released from the atomic bombs detonated at Hiroshima and Nagasaki,[49][58][59][60] but much less than the 50 to 57 Mt (210 to 240 PJ) Tsar bomb.[61] Also, unlike a nuclear explosion the object and its fragments did not release all of its energy at once, with the total radiated energy of the fireball, which generated the main explosion, predicted to have emitted an energy equivalent to ~ 90 kilotons of TNT (~ 0.4 PJ), according to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[56]

About 1,500 people were injured, two seriously. All of the injuries were due to indirect effects rather than the meteor itself, mainly from broken glass from windows that were blown in when the shock wave arrived, several minutes after the bright flash.[58][62] Initially 4,300,[63][64] later 7,200 buildings in six cities across the region were reported to have been damaged by the explosion.

With an estimated initial mass of 11,000 tonnes, and measuring approximately 17 to 20 meters across,[56] the Chelyabinsk meteor is the largest object[65] to have entered Earth's atmosphere since the 1908 Tunguska event and the 1930 Brazilian event,[66] and it is the only meteor known to have resulted in a large number of injuries.[64] The object had not been detected before atmospheric entry.[67]

Close approaches

On August 10, 1972 a meteor that became known as 1972 Great Daylight Fireball was witnessed by many people moving north over the Rocky Mountains from the U.S. Southwest to Canada. It was an Earth-grazing meteoroid that passed within 57 kilometers (about 34 miles) of the Earth's surface. It was filmed by a tourist at the Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming with an 8-millimeter color movie camera.[68]

On March 23, 1989 the 300-meter (1,000-foot) diameter Apollo asteroid 4581 Asclepius (1989 FC) missed the Earth by 700,000 kilometers (430,000 mi) passing through the exact position where the Earth was only 6 hours before. If the asteroid had impacted it would have created the largest explosion in recorded history, 12 times as powerful as the Tsar Bomba, the most powerful nuclear bomb ever exploded. It attracted widespread attention as early calculations had its passage being as close as 64,000 km (40,000 mi) from the Earth, with large uncertainties that allowed for the possibility of it striking the Earth.[69]

On March 18, 2004, LINEAR announced a 30-meter asteroid, 2004 FH, which would pass the Earth that day at only 42,600 km (26,500 mi), about one-tenth the distance to the Moon, and the closest miss ever noticed. They estimated that similar-sized asteroids come as close about every two years.[70]

On March 31, 2004, two weeks after 2004 FH, meteoroid 2004 FU162 set a new record for closest recorded approach, passing Earth only 6,500 km (4,000 mi) away (about one-sixtieth of the distance to the Moon). Because it was very small (6 meters/20 feet), FU162 was detected only hours before its closest approach. If it had collided with Earth, it probably would have harmlessly disintegrated in the atmosphere.

On March 2, 2009, near-Earth asteroid 2009 DD45 flew by Earth at about 13:40 UT. The estimated distance from Earth was 72,000 km (45,000 mi), approximately twice the height of a geostationary communications satellite. The estimated size of the space rock was about 35 meters (115 feet) wide.[71]

On January 13, 2010 at 12:46 UT, near-Earth asteroid 2010 AL30[72] passed at about 122,000 km (76,000 mi). It was approximately 10–15 m (33–49 ft) wide. If 2010 AL30 had entered the Earth's atmosphere, it would have created an air burst equivalent to between 50 kt and 100 kt (kilotons of TNT). The Hiroshima "Little Boy" atom bomb had a yield between 13-18 kt.[73]

On June 28, 2011 an asteroid designated 2011 MD, estimated at 5–20 m (16–66 ft) in diameter, passed within 20,000 km (12,000 mi) of the Earth, passing over the Atlantic Ocean.[74]

On November 8, 2011 2005 YU55 (at about 400m diameter) passed within 324,600 km (201,700 mi) (0.85 lunar distances) of Earth. Ten weeks later, on January 27, 2012, the 10-metre wide asteroid 2012 BX34 passed a mere 60,000 km (37,000 mi) from Earth.[75]

On February 15, 2013, 2012 DA14 passed approximately 27,700 km (17,200 mi) above the surface of Earth. This was closer than satellites in geosynchronous orbit. The asteroid was not visible to the unaided eye.

Future impacts

Although there have been a few false alarms, a number of objects have been known to be threats to the Earth. (89959) 2002 NT7 was the first asteroid with a positive rating on the Palermo Technical Impact Hazard Scale, with approximately one in a million on a potential impact date of February 1, 2019; it is now known that on January 13, 2019, 2002 NT7 will safely pass 0.4078 AU (61,010,000 km; 37,910,000 mi) from the Earth.[76]

Asteroid (29075) 1950 DA was lost after its discovery in 1950, since not enough observations were made to allow plotting of its orbit, and then rediscovered on December 31, 2000. The chance it will impact Earth on March 16, 2880, during its close approach has been estimated as 1 in 300. This chance of impact for such a large object is roughly 50% greater than that for all other such objects combined up until 2880.[77] It has a diameter of about a kilometer (0.6 miles). The next radar opportunity for 1950 DA is in 2032,[78] and our knowledge of the orbit won't improve considerably until then.

Only the asteroids 99942 Apophis (provisionally known as 2004 MN4) and (144898) 2004 VD17 have briefly had above-normal rankings on the Torino Scale.

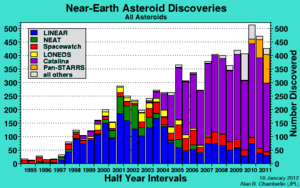

Projects to minimize the threat

Several surveys have undertaken "Spaceguard" activities (an umbrella term), including Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR), Spacewatch, Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT), Lowell Observatory Near-Earth-Object Search (LONEOS), Catalina Sky Survey, Campo Imperatore Near-Earth Object Survey (CINEOS), Japanese Spaceguard Association, and Asiago-DLR Asteroid Survey. In 1998, the United States Congress mandated the Spaceguard Survey – detection of 90% of near-earth asteroids over 1 km diameter (which threaten global devastation) by 2008. In 2005, this was extended by the George E. Brown, Jr. Near-Earth Object Survey Act, which calls for NASA to detect 90% of NEOs with diameters of 140 meters or greater, by 2020.[79]

As of 2011, 911 of the largest (>1 km diameter) near-Earth asteroids have been found, with an estimate of 70 yet to be found.[9]

See also

- 6Q0B44E, in Earth orbit with a period of 80 days

- Asteroid mining

- Bolide

- BRAMS (Belgian Radio Meteor Stations); study of meteor population[80]

- Co-orbital configuration

- CubeSat

- Euronear

- J002E3, probably the third stage of the Apollo 12 Saturn V

- List of Earth-crossing minor planets

- Mission Marco Polo

- 2010 SO16

- Near Earth Object Camera

- NEODyS

- Orbit@home

- Potentially hazardous object

- Quasi-satellites and trojans

- Space debris

- Spaceguard

References

- ↑ "ESA/ESO Collaboration Successfully Tracks Its First Potentially Threatening Near-Earth Object". ESO Announcement. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "NEO Groups". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Richard Monastersky (March 1, 1997). "The Call of Catastrophes". Science News Online. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "The IAU and Near Earth Objects". Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 A. Morbidelli, W. F. Bottke Jr., Ch. Froeschlé, P. Michel; Bottke; Froeschlé; Michel (January 2002). "Origin and Evolution of Near-Earth Objects" (PDF). In W. F. Bottke Jr., A. Cellino, P. Paolicchi, and R. P. Binzel. Asteroids III (University of Arizona Press): 409–422. Bibcode:2002aste.conf..409M.

- ↑ Clark R. Chapman (May 2004). "The hazard of near-Earth asteroid impacts on earth". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 222 (1): 1–15. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.222....1C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.03.004.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Shiga, David (2006-06-27). "New telescope will hunt dangerous asteroids". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-11-15.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "NEO Discovery Statistics". Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "WISE Revises Numbers of Asteroids Near Earth". NASA/JPL. 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2012-05-17. (NASA Space Telescope Finds Fewer Asteroids Near Earth)

- ↑ "Potentially Hazard Asteroids". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ NEO Earth Close Approaches at NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office

- ↑ Dan Vergano (February 2, 2007). "Near-Earth asteroids could be 'steppingstones to Mars'". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Rui Xu, Pingyuan Cui, Dong Qiao and Enjie Luan (18 March 2007). "Design and optimization of trajectory to Near-Earth asteroid for sample return mission using gravity assists". Advances in Space Research 40 (2): 200–225. Bibcode:2007AdSpR..40..220X. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.03.025.

- ↑ Donald Savage and Michael Buckley (January 31, 2001). "NEAR Mission Completes Main Task, Now Will Go Where No Spacecraft Has Gone Before". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Don Yeomans (August 11, 2005). "Hayabusa's Contributions Toward Understanding the Earth's Neighborhood". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Emily Lakdawalla. "Chang'e 2 imaging of Toutatis".

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Portree, David S. (2013-03-23). "Earth-Approaching Asteroids as Targets for Exploration (1978)". Wired. Retrieved 2013-03-27. "People in the early 21st century have been encouraged to see asteroids as the interplanetary equivalent of sea monsters. We often hear talk of “killer asteroids,” when in fact there exists no conclusive evidence that any asteroid has killed anyone in all of human history. ... In the 1970s, asteroids had yet to gain their present fearsome reputation ... most astronomers and planetary scientists who made a career of studying asteroids rightfully saw them as sources of fascination, not of worry."

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Fernández Carril, Luis (2012-05-14). "The evolution of near Earth objects risk perception". The Space Review. Retrieved 2012-05-25.

- ↑ "THE PALERMO TECHNICAL IMPACT HAZARD SCALE". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. 31 August 2005. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ "The flux of small near-Earth objects colliding with the Earth" by P. Brown et al., Nature, 420, pp. 294–6, November 2002.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 "Current Impact Risks". Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Asteroid 1950 DA". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ↑ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: asteroids and NEOs and H < 16 (mag)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- ↑ The Torino Impact Hazard Scale

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: asteroids and NEOs and H > 25 (mag)". JPL Small-Body Database. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Jane Platt (January 12, 2000). "Asteroid Population Count Slashed". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ David Rabinowitz, Eleanor Helin, Kenneth Lawrence and Steven Pravdo (13 January 2000). "A reduced estimate of the number of kilometer-sized near-Earth asteroids". Nature 403 (6766): 165–166. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..165R. doi:10.1038/35003128. PMID 10646594. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ D.F. Lupishko and T.A. Lupishko (May 2001). "On the Origins of Earth-Approaching Asteroids". Solar System Research 35 (3): 227–233. Bibcode:2001SoSyR..35..227L. doi:10.1023/A:1010431023010.

- ↑ A. Morbidelli, D. Vokrouhlický (May 2003). "The Yarkovsky-driven origin of near-Earth asteroids". Icarus 163 (1): 120–134. Bibcode:2003Icar..163..120M. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00047-2.

- ↑ D.F. Lupishko, M. di Martino and T.A. Lupishko; Di Martino; Lupishko (September 2000). "What the physical properties of near-Earth asteroids tell us about sources of their origin?". Kinematika i Fizika Nebesnykh Tel Supplimen 3 (3): 213–216. Bibcode:2000KFNTS...3..213L.

- ↑ Kresak, L'. (1978). "The Tunguska object – A fragment of Comet Encke". Astronomical Institutes of Czechoslovakia (Astronomical Institutes of Czechoslovakia) 29: 129. Bibcode:1978BAICz..29..129K.

- ↑ "Closest Approaches to the Earth by Comets". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Robert Marcus, H. Jay Melosh, and Gareth Collins (2010). "Earth Impact Effects Program". Imperial College London / Purdue University. Retrieved 2013-02-04. (solution using 2600kg/m^3, 17km/s, 45 degrees)

- ↑ Clark R. Chapman & David Morrison (January 6, 1994). "Impacts on the Earth by asteroids and comets: assessing the hazard". Nature 367 (6458): 33–40. Bibcode:1994Natur.367...33C. doi:10.1038/367033a0

- ↑ Asher, D. J.; Bailey; Emel'Yanenko; Napier; Bailey, M.; Emel'Yanenko, V.; Napier, W. (2005). "Earth in the Cosmic Shooting Gallery". The Observatory 125 (2): 319–322. Bibcode:2005Obs...125..319A.

- ↑ Christopher F. Chyba, Paul J. Thomas & Kevin J. Zahnle (January 7, 1993). "The 1908 Tunguska explosion: atmospheric disruption of a stony asteroid". Nature 361 (6407): 40–44. Bibcode:1993Natur.361...40C. doi:10.1038/361040a0.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Reza, Ramiro de la. O evento do Curuçá: bólidos caem no Amazonas (The Curuçá Event: Bolides Fall in the Amazon) (Portuguese), Rio de Janeiro: National Observatory. Retrieved from the Universidade Estadual de Campinas website.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Reza, Ramiro de la; Martini, P. R.; Brichta, A.; Lins de Barros, H.; Serra, P.R.M. The Event Near The Curuçá River, presented at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: 67th Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting, August 2–6, 2004. Retrieved from Universities Space Research Association (USRA) website, Columbia, MD.

- ↑ Lienhard, John H. Meteorite at Curuçá, The Engines of Our Ingenuity, University of Houston with KUHF-FM Houston.

- ↑ McFarland, John. The Day the Earth Trembled, Armagh, Northern Ireland: Armagh Observatory website, last revised on November 10, 2009.

- ↑ P. Brown, R.E. Spalding, D.O. ReVelle, E. Tagliaferri and S.P. Worden (21 November 2002). "The flux of small near-Earth objects colliding with the Earth" (PDF). Nature 420 (6913): 294–296. doi:10.1038/nature01238. PMID 12447433. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Don Yeomans (October 6, 2008). "Small Asteroid Predicted to Cause Brilliant Fireball over Northern Sudan". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Richard A. Kerr (6 October 2008). "FLASH! Meteor to Explode Tonight". ScienceNOW Daily News. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Don Yeomans (October 7, 2008). "Impact of Asteroid 2008 TC3 Confirmed". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Richard A. Kerr (8 October 2008). "Asteroid Watchers Score a Hit". ScienceNOW Daily News. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ P. Jenniskens et al. (2009-03-26). "The impact and recovery of asteroid 2008 TC3". Nature 458 (7237): 485–488. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..485J. doi:10.1038/nature07920. PMID 19325630. Archived from the original on 2009-06-01. Retrieved 2009-04-04. Published in Letters to Nature

- ↑ Little Asteroid Makes a Big Splash Sky and Telescope, October 9, 2008.

- ↑ Don Yeomans, Paul Chodas and Steve Chesley (October 23, 2009). "Asteroid Impactor Reported over Indonesia". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved 2009-10-30.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 Agle, D. C. (13 February 2013). "Russia Meteor Not Linked to Asteroid Flyby". NASA news. NASA. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Arutunyan, Anna; Bennetts, Marc. "Meteor in central Russia injures at least 500". USA Today. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Heintz, Jim; Isachenkov, Vladimir (15 February 2013). "100 injured by meteorite falls in Russian Urals". Mercury News. Associated Press. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Major, Jason (15 February 2013). "Meteor Blast Rocks Russia". Universe Today. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ "CBET 3423 : 20130223 : Trajectory and Orbit of the Chelyabinsk Superbolide". Astronomical Telegrams. International Astronomical Union. 2013-02-23. Archived from the original on 2013-02-23.(registration required)

- ↑ "Russian Meteor strike eyewitnesses speak". YouTube. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013. "In Russian, with translation voiceover in English"

- ↑ Cooke, William (15 February 2013). "Orbit of the Russian Meteor". NASA blogs. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 Yeomans, Don; Chodas, Paul (1 March 2013). "Additional Details on the Large Fireball Event over Russia on Feb. 15, 2013". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- ↑ "Meteor threat wasn't expected for another 2,000 years – Russian Emergency Minister". RT. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 "Meteorite hits Russian Urals: Fireball explosion wreaks havoc, up to 1,200 injured (PHOTOS, VIDEO)". RT. 15 February 2013.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Russian meteorite blast explained: Fireball explosion equal to 20 Hiroshimas". RT. 15 February 2013.

- ↑ "Russian meteor hit atmosphere with force of 30 Hiroshima bombs". The Telegraph. 16 February 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ "The Tsar Bomba ("King of Bombs")". Retrieved 2005-01-01-2006.

- ↑ Heintz, Jim; Isachenkov, Vladimir (15 February 2013). "Meteor explodes over Russia's Ural Mountains; 1,100 injured as shock wave blasts out windows". Postmedia Network Inc. The Associated Press. Retrieved 4 March 2013. "Emergency Situations Ministry spokesman Vladimir Purgin said many of the injured were cut as they flocked to windows to see what caused the intense flash of light, which momentarily was brighter than the sun."

- ↑ Marson, James; Naik, Gautam (15 February 2013). "Falling Meteor Explodes Over Russia". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Ewalt, David M (15 February 2013). "Exploding Meteorite Injures A Thousand People in Russia". Forbes. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Brumfiel, Geoff (15 February 2013). "Russian meteor largest in a century". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.12438. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Lienhard, John H. "Meteorite at CURUÇA". Retrieved 4 March 2013. "This explosion was only 1/10 as powerful as the Tunguska explosion. Yet that's still 50 times as powerful as the Hiroshima bomb."

- ↑ "Neil deGrasse Tyson: Radar could not detect meteor". Today. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Grand Teton Meteor Video, Youtube

- ↑ Brian G. Marsden (1998-03-29). "HOW THE ASTEROID STORY HIT: AN ASTRONOMER REVEALS HOW A DISCOVERY SPUN OUT OF CONTROL". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Steven R. Chesley and Paul W. Chodas (March 17, 2004). "Recently Discovered Near-Earth Asteroid Makes Record-breaking Approach to Earth". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Yahoo News – 20090302 – Asteroid Flies Past Earth

- ↑ Small Asteroid 2010 AL30 Will Fly Past The Earth. NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program, January 12, 2010.

- ↑ Near-Earth Object 2010 AL30. NASA Earth Science Picture of the Day March 06, 2010.

- ↑ "Asteroid soars over Atlantic Ocean". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. June 28, 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-03.

- ↑ "Asteroid makes near-miss fly-by". British Broadcasting Corporation. 27 January 2012. Retrieved 2012-01-28.

- ↑ "JPL Close-Approach Data: 89959 (2002 NT7)". 2011-09-12 last obs (arc=57 years). Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ Giorgini, J. D.; Ostro, S. J.; Benner, L. A. M.; Chodas, P. W.; Chesley, S. R.; Hudson, R. S.; Nolan, M. C.; Klemola, A. R. et al. (April 5, 2002). "Asteroid 1950 DA's Encounter with Earth in 2880: Physical Limits of Collision Probability Prediction" (PDF). Science 296 (5565): 132–136. Bibcode:2002Sci...296..132G. doi:10.1126/science.1068191. PMID 11935024. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ↑ Giorgini, J. D.; Ostro, S. J; Benner, L. A. M.; Chodas, P.W.; Chesley, S.R.; et al. (2002). "Asteroid 1950 DA's Encounter With Earth in 2880: Physical Limits of Collision Probability Prediction". Science 296 (5565): 132–136. Bibcode:2002Sci...296..132G. doi:10.1126/science.1068191. PMID 11935024.

- ↑ Public Law 109–155, Section 321 (d).

- ↑ Belgian RAdio Meteor Stations

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Near-Earth asteroids. |

- Near earth object program — Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Observable Near-Earth Asteroids — Lowell Observatory

- Sormano Astronomical Observatory: Table of Asteroids Next Closest Approaches to the Earth — Sormano Astronomical Observatory

- Asher, D.J.; Bailey, M.; Emel’yanenko, V.; Napier, B. (2005), "Earth In The Cosmic Shooting Gallery", The Observatory 125: 319–322, Bibcode:2005Obs...125..319A

- Catalogue of the Solar System Small Bodies Orbital Evolution — Samara State Technical University

- NASA Space Telescope Finds Fewer Asteroids Near Earth — NASA

- Current Map Of The Solar System — Armagh Observatory

| |||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||