Nazi architecture

Nazi architecture was an architectural plan which played a role in the Nazi party's plans to create a cultural and spiritual rebirth in Germany as part of the Third Reich.

Adolf Hitler was an admirer of imperial Rome and believed that some ancient Germans had, over time, become part of its social fabric and exerted influence on it. He considered the Romans an early Aryan empire, and emulated their architecture in an original style inspired by both neoclassicism and art deco, sometimes known as "severe" deco, erecting edifices as cult sites for the Nazi Party. He also ordered construction of a type of Altar of Victory, borrowed from the Greeks, who were, according to Nazi ideology, inseminated with the seed of the Aryan peoples. At the same time, because of his admiration for the Classical cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, he could not isolate and politicize German antiquity, as Benito Mussolini had done with respect to Roman antiquity. Therefore he had to import political symbols into Germany and justify their presence on the grounds of a spurious racial ancestry, the myth that ancient Greeks were among the ancestors of the Germans - linked to the same Aryan peoples.[1]

Hitler's desire to be the founder of a thousand-year Reich were in harmony with the Colosseum being associated with eternity. He envisioned all future Olympic games to be held in Germany in the Deutsches Stadion. He also anticipated that after winning the war, other nations would have no choice but to send their athletes to Germany every time the Olympic games were held. Thus, the architecture foreshadowed Hitler's craving for control of the world long before his aim was put into words.[2] Hitler also seemed to derive satisfaction from seeing world-famous monuments being surpassed in size by German equivalents.

Most regimes, especially new ones, wish to make their mark both physically and emotionally on the places they rule. The most tangible way of doing so is by constructing buildings and monuments. Architecture is considered to be the only art form that can actually physically meld with the world as well as influence the people who inhabit it.[citation needed] Buildings, as autonomous things, must be addressed by the inhabitants as they go about their lives. In this sense, people are "forced" to move in certain ways, or to look at specific things. In so doing, Architecture affects not only the landscape, but also the mood of the populace who are served. The Nazis believed architecture played a key role in creating their new order. Architecture had a special importance to the politicians who sought to influence all aspects of human life.

Architecture falls under cultural landscape, one of the most reflective relics of a culture. The cultural landscape of a nation and era very directly mirror the customs, practices, and ideology of the society in which the landscape is made.

Moreover, not only major cities but also small villages were to express the achievement and the nature of the German people. It seemed as though the basic design of commonly practiced architecture at the time was to be either left in place or modified within Germany's dominion. The new building style may have been intended to give the idea to the rest of the world and to the unconverted Germans that the era of the thousand-year Reich had dawned.

Hitler the architect

Hitler had fostered an appreciation of the fine arts since his youth; his particular interests were in architecture. He was proud of his German heritage, extending this belief into his view of the arts, and often compared Munich to Vienna, two cities in which he resided. In his dictated autobiography Mein Kampf, he commented that Munich was "the metropolis for German art" and stressed the fact that it was a purely German city. However, his critiques of German cities in the interwar period were that they lacked a sense of national community. He criticized the Reichtstag Building as such.

Hitler was quite fond of the numerous theatres built by Hermann and Ferdinand Fellner, who built in the late baroque style. In addition, he appreciated the stricter architects of the 19th century such as Gottfried Semper, who built the Dresden Opera House, the Picture Gallery in Dresden, the court museums in Vienna and Theophil Freiherr von Hansen, who designed several buildings in Athens in 1840. He raved about the Palais Garnier, home of the Paris Opera, and the Law Courts of Brussels by the architect Poelaert.

Ultimately, he was always drawn back to inflated neo-baroque such as Kaiser Wilhelm II had fostered, through his court architect Ernst von Ihne. Fundamentally, it was decadent baroque comparable to the style that accompanied the decline of the Roman Empire. Thus, in the realm of architecture, as in painting and sculpture, Hitler really remained arrested in the world of his youth: the world of 1880 to 1910, which stamped its imprint on his artistic taste as on his political and ideological conceptions.[3]

The Führer did not have one particular style; there was no official architecture of the Reich, only the neoclassical baseline that was enlarged, multiplied, altered and exaggerated. Hitler appreciated the permanent qualities of the classical style as it had a relationship between the Dorians and his own Germanic world.

Three primary roles

Nazi architecture has three primary roles in the creation of its new order: (i) Theatrical; (ii) Symbolic; (iii) Didactic. In addition, the Nazis saw architecture as a method of producing buildings that had a function, but also served a larger purpose. For example, the House of German Art had the function of housing art, but through its form, style and design it had the purpose of being a community structure built using an Aryan style, which acted as a kind of temple to acceptable German art.

Stage

Many Nazi buildings were stages for communal activity, creations of space meant to embody the principles on which Nazi ideology was based. From Albert Speer's use of banners for the May Day celebrations in the Lustgarten, to the Nazi co-option of the Thing tradition, the Nazis wanted to link themselves to a German past.

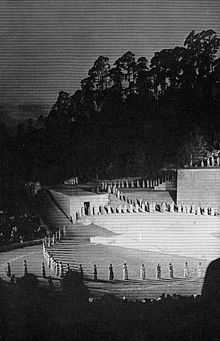

The link could be direct; a Thingplatz (or Thingstätte) was a meeting place near or directly on a site of supposed special historical significance, used for the holding of festivals associated with a Germanic past. This was an attempt to link the German people back to both their history and their land. The use of 'Thing' places was closely associated with the 'blood and soil' part of Nazi ideology, which involved the perceived right of those of German blood to occupy German land. The Thingplatz would contain structures, which often included natural objects like stones and were built in the most natural setting possible. These structures would be built following the pattern of an ancient Greek theatre, following a structure of a historical culture considered to be Aryan. This stressing of a physical link between the past and Nazism aided to legitimatize the Nazi view of history, or even the Nazi regime itself. Still, the 'Thing' movement was not successful.

The link could be indirect; the May Day celebrations of 1936 in Berlin took place in a Lustgarten that had been transformed into a stage. This transformation was not the standard dressing of a specific place but a creation of a new anonymous, pure, cubic space that freed itself from the immediate history of Berlin, the church and the monarchy, yet was still associated with the distant aura of a Hellenic past. This was simply the creation of a new ceremonial place in direct competition with the former Royal Palace and Altes Museum, both even in the 1930s, still symbols of a royal Berlin. The symbolism was clear; any speaker at the event would be standing in front of the Altes Museum, which housed Germany's classical collection that could be seen by the audience only through Nazi banners. There was a link between the new order and the classical past, but the new order was paramount.

The Nazis would bring the community together using architecture, creating a stage for the community experience. These buildings were also solely for the German people, the great hall in Berlin was not a supranational People's House like those being built in the Soviet Union, but the stage where tens of thousands of recharged citizens would enter into a solemn mystic union with the Supreme Leader of the German Nation. The sheer size of the stage itself would magnify the importance of what was being said.

How these stages were set was also an issue, from the most mundane building to the grandest, the form and style used in their construction tell a great deal about and are symbols of those who created them, when they were created and why they were created. Designs of this kind occasionally occur by accident; however, the architectural styles speak to the tastes of those who constructed the building or paid for its construction. It also speaks to the tastes of the general architectural movements of the time and the regional variants that influenced them. Nazi buildings were an expression of the essence of the movement, built as a National Socialist building should be, regardless of the style used.

Symbolic

Determining what National Socialists saw as the concept of Nazi Architecture is problematic. Various members of the leadership had differing views and tastes and commentators see the same style in different ways. Roger Eatwell sees the format used at the Nuremberg rallies as a mixture of Catholic ceremony and left-wing Expressionist form and lighting, while Sir Nevile Henderson saw a cathedral of ice. Still, if a building was designed and built using the Nazi version of what was German, it was considered Nazi Architecture.

In general, there were two primary National Socialist styles of architecture. Nazi Architecture in its crudest sense was either a squared-off version of neoclassical architecture, or a mimicry of völkisch and national romanticism in buildings and structures. The most notable example of this is the Wewelsburg castle complex redesigned in a very mythological way as a cult site for the SS. Especially in the North Tower of the castle medieval Romanesque and Gothic architecture was imitated. The Wewelsburg was to become "centre of the world".

The neoclassical style was primarily used for urban state buildings or party buildings such as the Zeppelin Field in Nuremberg, the planned Volkshalle for Berlin and the Dietrich Eckart Stage in Berlin. This style was not just used for physical construction, but on the ordered columns of searchlights that formed Speer's "cathedral of light" used at the Nuremberg Party Rallies.

The völkish style was primarily used in rural settings for accommodation or community structures like the Ordensburg in Krössinsee, the walls and watchtowers of KL Flossenbürg and KL Mauthausen. It was also to be applied to rural new towns as it represented a mythical medieval time when Germany was free of foreign and cosmopolitan influences. This style was also used in a limited way for buildings with modern uses like weather service broadcasting and the administration building for the federal post office.

Most Nazi Architecture was novel neither in style nor concept; it was not supposed to be. Even a cursory inspection of what was intended for Berlin finds analogies all over the world. Long boulevards with important buildings along them can be found in the grid pattern road structures of Washington and New York, the Mall and Whitehall in London, and the boulevards of Paris. Large domes can be found on the buildings of the Mughal Empire of India, the Capitol in Washington, the Pantheon and Basilica di San Pietro in Rome. Even the "Kraft durch Freude" ("Strength through Joy") resort at Prora is not wholly unlike the buildings envisaged by Le Corbusier in his "City of Three Million Inhabitants". The building of a formal governmental zone outside the centre of an old city or totally on its own had become commonplace by the 1930s. This is not to say their plans were simply an attempt to copy others, but that they were following a pattern already established in human society. The forms used may have been inspired by other city redevelopment plans like Edwin Lutyens' Delhi, Burnham's Chicago or even Walter Burley Griffin's Canberra.

National Socialism is often viewed as anti-modern and romantic or having a pragmatic willingness to use modern means in pursuit of anti-modern purposes. This confuses the Nazi dislike of certain styles like the Bauhaus with a blanket dislike of all modern styles. This was based mainly on what the Bauhaus and others were seen as representing, like foreign influences or the decadence of the Weimar Republic. The lack of any human scale details or plain exteriors may have produced an overwhelming effect, but this style was common from the 1910s onwards. This modern approach was not limited to the neo-classical buildings for city centres, but was also used for völkisch buildings like Ordensburgs and Autobahn garages.

The neo-classical style used was not novel for the time; it was firmly anchored in time. Speer's style was assimilating the international 1930s style of public architecture, which was then being pursued as a modernising classicism. This is in direct contrast to Peter Adams's attempts to separate Nazi art from the Zeitgeist and present it as something that can be looked at through only the lens of Auschwitz. This is trying to establish by default a thesis that ugly regimes must produce ugly buildings and such regimes are so evil that everything they produce must be evil or third-rate. The reality was that destroying to build anew was a standard polemical gesture of the Modernist movement and the styles chosen were not unlike the ones being used at the time. To criticize Speer's architectural style is to criticise buildings being built at the same time all over the world. Ultimately, Nazi Architecture was not supposed to be pleasing; its purpose was to fulfil its task.

Hitler saw the buildings of the past as direct representations of the culture that created them and how they were created. Hitler believed they could be used by man to transmit his time and its spirit to posterity and that in his time, ultimately, all that remained to remind men of the great epochs of history was their monumental architecture. Nazi Architecture should speak to the conscience of a future Germany centuries from now. As Hitler said in a speech, "The purpose of Nazi architecture and technology should be to create ruins that would last a thousand years and thereby overcome the transience of the market".[4]

Central to this was Albert Speer's Theory of Ruin Value, in which the Nazis would build structures which even in a state of decay, after hundreds or thousands of years would more or less resemble Roman models. Speer intended to produce this result by avoiding elements of modern construction such as steel girders and reinforced concrete which are subject to weathering and by designing his buildings to withstand the impact of the wind even if the roofs and ceilings were so neglected that they no longer braced the walls. In this respect, it can be seen that by going back to the materials of the past and by the proper engineering of buildings it was possible to create a permanence that was impossible with contemporary building materials and styles. It has been suggested that the use of stone was more a result of economic necessity or the product of an attempt by the SS to build up a stable position within the German economy, but both are at most secondary to the desire for the permanence stone gives. To Hitler, only the great cultural documents of humanity made of granite and marble could symbolize his new order.

The theory of ruin value could be seen as a backward looking concept; however, what it actually does is look at the types of buildings that survive from the past, understand why they survived, and attempt to build the new buildings of the Reich based on such understanding. In addition, the infrastructure and organization behind the provision of building material was purely of the time. Hitler was not like Shelley's Ozymandias, a leader boasting about his power to the future, but rather a builder of symbolic expressions of the Nazi movement and of the new Germany they would create.

Nazi buildings were not to be like the Reichstag, seen as a grandiose monument conjuring up historical reminiscences, but as symbols of a new Germany. The buildings had to be suitable for their intended role. An example of this is the rebuilt Reichskanzlei that was planned as a symbol of the Greater German Reich, which included Austria even though at the time of planning the Anschluss was still three years away. So important was the symbolism of the buildings that their form was decided on long before their construction and in some cases, even before the events they were to symbolize. Speer himself remarked that many of the buildings Hitler asked him to construct were glorifying the victories he didn't yet have in his pocket. Hitler drew sketches of buildings he hoped to build as early as the 1920s, when there was not a shred of hope that they could ever be built. The buildings had to look the part: the Reichskanzlei must look like the centre of the Reich, not the headquarters of a soap company. Nazi buildings would be the great cultural documents that the new order would create in their stronger, protected community.

Symbolic architecture need not be built as it often already existed. In 1941 the SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps published an essay by Heinrich Himmler entitled "German Castles in the East", in which he wrote, "When people are silent, stones speak. By means of the stone, great epochs speak to the present so that fellow citizens; are able to uplift themselves through the beauty of self-made buildings. Proud and self-assured, they should be able to look upon these works erected by their own community". Himmler continues by creating a cyclical process linking the people, their blood and their buildings, "Buildings are always erected by people. People are children of their blood, are members or their race. As blood speaks, so the people build".

Where buildings held important cultural items, they would either be remodelled like Brunswick Cathedral, which was the burial place of Henry the Lion, co-opted like Strasbourg Cathedral as the monument to Germany's unknown soldier, or moved to a more appropriate position, like the Victory Column in Berlin.

Like the Sacré-Coeur basilica in Montmartre or the Flavian Amphitheatre in Rome, the new buildings of the National Socialists would replace the commercial buildings that were signs of the cultural decay and general break-up of the Berlin of the 1930s. To express their true Aryan nature, the Nazis had to destroy the creations of non-Germans and the decadent past and accept Hitler's judgment as to which way German art must go in order to fulfil its task as the expression of German character. The new Berlin, like the new National Socialist Germany, would superimpose itself onto the decadence of the old. The Nazi vision of a city would replace the visions of the past, they would replace the twilight, or the past, with clarity, cleanliness, and pure, distinct lines.

Symbols were not just limited to permanent buildings; familiar symbols of the north European past were used regularly in the decorations for Nazi festivals. An example of this is the use of the Maypole at the May Day celebrations. It is the traditional symbol throughout northern Europe of the end of winter and of the reawakening of nature and the focus of community events. At the doors of the German Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exhibition were two sets of seven meter high statues that symbolized family and community. The pavilion that was designed as a blatant symbol of Nazi Germany was planned by a German, Albert Speer and built solely out of German materials shipped from within Germany.Symbolism, graphic art and hortatory inscriptions were prominent in all forms of Nazi-approved architecture. The eagle with the wreathed swastikas, heroic friezes and free-standing sculpture were common. Often mottoes or quotations from Mein Kampf or Hitler's speeches were placed over doorways or carved into walls. The Nazi message was conveyed in friezes, which extolled labour, motherhood, the agrarian life and other values. Muscular nudes, symbolic of military and political strength, guarded the entrance to the Berlin Chancellery[5]

The Ordensburgen are the schools at which the ideology of National Socialism is taught to a picked group of youths who desire to dedicate their lives to political service. The Ordensburgen's architectural form derives from the fortresslike castles built by the Teutonic Knights whose mission it was to civilise and colonise the lands east of the Elbe. Since it is the mission of the Ordensburg to train and develop a new order of leaders who are to take with them into practical life the ideals of the movement which they serve, this form represents an appropriate architectural symbol.[6]

The three NSDAP-Ordensburgen were Ordensburg Krössinsee, Ordensburg Sonthofen and Ordensburg Vogelsang.

Didactic

Hitler saw architecture as "The Word In Stone," a method of imparting a message. This is not regime architecture primarily for general propaganda purposes as argued by Benton, but is work meant to impart a specific message. This would be a message that all decent Germans would understand, like the lessons of events at the Degenerate Art exhibition staged in Munich in 1937. They would not understand it because they were told to; they would understand it simply because of who they were.

The Nazis chose new versions of past styles for most of their architecture. This should not be viewed simply as an attempt to reconstruct the past, but rather an effort to use aspects of the past to create a new present. Most buildings are copies in some form or other, but for the Nazis, copying the past not only linked them to the past in general but also specifically to an Aryan past. Neo-classical architecture and Renaissance architecture were direct representations of Aryan culture. Völkish architecture was also Aryan but of a Germanic nature. Still, these analogues were not part of an attempt to recreate an actual past, but were meant to emphasize the importance of Aryan culture as a justification for the actions of the present. Many other nations from the Austro Hungarian Empire to the United States have constructed major government buildings in historical styles to get across a specific message.

While Hitler saw the architecture of the Weimar Republic as an object lesson in cultural decline, the new buildings he would build would teach a different lesson, that of national rebirth. The size of the buildings proposed for Berlin would be among the largest in the world, meant to instill in each individual German citizen the insignificance of individuals in relation to the community as a whole. The distinct lack of any detailing at a human scale in the urban neo-classical building would have simply overawed, imparting the message without any subtlety. If the message was not understood it would be drummed in by making people go in straight lines to predetermined positions. The message of community would even affect holidays. Clemens Klotz's Prora would not only have a Festhalle in which people would hear speeches and get involved in communal events but also give everyone the same view of the sea.

Engineering could be coupled with architecture to teach lessons too. It is clear that the Autobahn was seen as a way of creating a community, which was both physically and symbolically linked. When Carl Theoder Protzen entitled his painting of the Autobahn bridge at Leipheim, "Clear the forest - dynamite the rock; conquer the valley; overcome the distance; stretch the road through the German land," he was linking clear connections between what should be done and what it was to accomplish. Building the Autobahn would not only teach the German people that they were linked together but also would show that it had been accomplished by Germans working together. It would be an inspiration for the construction of the community of the German People. The effort that went into the styling of Autobahn bridges and garages shows plainly that it was more than just a motorway. In some circumstances, the design used for the Autobahn actually affects the functioning of its supposed purpose.

The role the Nazis hoped architecture would play in the creation of a new order was like that of a book: to provide a place to hold the message, the symbols to impart it and a teacher to read it. Architecture, like every other art form, would be produced to serve the new Nazi order. For them, if this meant following existing architectural styles or providing analogues of other buildings, then so it is.

Cult of victory

The Nazis planned and built many military trophies and memorials (Gr Mahnmäler), on the eastern borders of the Reich. In the same way, the Romans had built celebratory trophies on the borders of their empire to commemorate victories and warn off would-be attackers. One of the most prominent memorial buildings intended to commemorate Germany's past and anticipated military glory was Wilhelm Kreis's Soldatenhalle. This was to be yet another cult centre to promote the regime's glorification of war, patriotic self-sacrifice and virtutes militares. The main architectural features of this building were overtly Roman.[8] A groin-vaulted crypt (picture) beneath the main barrel-vaulted hall was intended as a pantheon of generals exhibited here in effigy. In addition, it functioned as a herõon, since the bones of Frederick the Great were to be placed in the building.[9]

Flags and insignia played an important part in Nazi ceremonial and in the decoration of buildings. The eagle-topped standards carried by the SA at Nuremberg rallies were reminiscent of Roman legionary standards, the uniformity of which Hitler admired.[10] There can be little doubt that Hitler's state architecture, even when seen today in photographs of architectural models, conveys a sense of "Power and Force" (Gr Macht und Gewalt), which of course Hitler wanted it to embody.[11]

Inevitably, after Hitler's defeat, the colossal dimensions of his buildings tended to be seen, as they were by Speer in his memoirs, as symbols of Hitler's megalomania. This is perhaps a valid view point, but it is also something of an oversimplification, since at the time the buildings were planned and erected, they were valid symbols of Germany's rapidly rising power and expressed the optimism generated by Hitler's spectacular initial victories. The vast public buildings of ancient Rome have rarely been explained as symptoms of imperial megalomania, except perhaps for the Domus Aurea, since Roman imperialism, which generated money and labour necessary for the erection of Rome's monumental buildings, was supremely successful and long-lived. Hitler's architecture is sometimes misjudged because he was building for the future in anticipation of a greatly enlarged Reich. Here it is worth noting that Vitruvius perceived that Augustus was building on a large scale for future greatness. Hitler's optimistic expectations were frustrated and in the aftermath of catastrophe his architectural plans seemed by many to be those of a madman. However difficult it may be to view these plans objectively, it would be a mistake to regard his buildings as either psychologically ineffective or symbolically impotent. This is certainly not the impression given by Speer or Giesler at the time they were articulating Hitler's architectural plans.[12]

Had Hitler achieved all his political and military aims and had his successors consolidated and perhaps even expanded his territorial gains, the art and architecture of Germany would undoubtedly have reflected the sentiment that pervaded much of Rome's art in the Augustan period, that is, a confidently assumed right to dominate others, which Virgil elegantly, if brutally, expressed in Aeneid 6.851-53: "Remember, Roman, to exercise dominion over nations. These will be your skills: to impose culture on peace, to spare the conquered and to war down the proud". This passage, so much in tune with Nazi aspirations is repeatedly referred to in the political literature of Germany at the time.

Berlin's reshaping

In Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler states that industrialized German cities of his day lacked dominating public monuments and a central focus for community life. In fact, criticism of the rapid industrialization of German cities after 1870 had already been voiced.[13]

The ideal Nazi city was not to be too large, since it was to reflect pre-industrial values and its state monuments, the products and symbols of collective effort (Gr.Gemeinschaftsarbeiten), were to be given maximum prominence by being centrally situated in the new and reshaped cities of the enlarged Reich.

Hitler's comments in Mein Kampf indicated that he saw buildings such as the Colosseum and the Circus Maximus as symbols of the political might and power of the Roman people. Hitler stated, "Architecture is not only the spoken word in stone, but also is the expression of the faith and conviction of a community, or else it signifies the power, greatness and fame of a great man or ruler". In Hitler's cultural address, "The Buildings of the Third Reich," delivered in September 1937, in Nuremberg, he affirmed that the new buildings of the Reich were to reinforce the authority of the Nazi party and the state and at the same time provide "gigantic evidence of the community" (Gr. gigantischen Zeugen unserer Gemeinschaft). The architectural evidence of this authority could already be seen in Nuremberg, Munich and Berlin and would become still more evident when more plans had been put into effect.

On September 19, 1933, Hitler told the mayor of Berlin that his city was "unsystematic", but it was not until January 30, 1937, that Speer was officially put in charge of plans for the reshaping of Berlin, although he had been working on them unofficially in 1936.

.jpg)

The plan that Speer coordinated as 'Inspector General of Construction' (GBI) for the centre of Berlin was based on Roman, not Greek, planning principles, which might or might not have been influenced by Roman-derived town plans in Fascist Italy. Speer's plan was to create a central north-south axis, which was to intersect the major east-west axis at right angles. On the north side of the junction a massive forum of about 350,000 square metres was planned, around which were to be situated buildings of the greatest political and physical dimensions: a vast domed Volkshalle on the north side, Hitler's vast new palace and chancellery on the west side and part of the south side, and on the east side the new High Command of the German armed forces and the now-dwarfed pre-Nazi Reichstag. These buildings were to be placed in strong axial relationship around the forum designed to contain one million people, and were collectively to represent the "maiestas imperii" (The Majesty of the Empire) and make the new world capital, Germania, outshine its only avowed rival, Rome.

The plan for the centre of Berlin differed only in its dimensions from the plans drawn up for the reshaping of smaller German cities and for the establishment of new towns in conquered territories. The order for the reshaping of other German cities was signed by Hitler on October 4, 1937.

In each town, the new community buildings were not to be sited randomly, but were to have prominent (usually central) positions within the town plan. The clarity, order and objectivity that Hitler aimed at in the layout of his towns and buildings were to be achieved in conquered territories in the East by founding new colonies and in Germany itself by reshaping the centres of already established towns and cities.[14] In order to provide a town with centrally located community centres, principles of town planning reminiscent of Greek, but more especially Roman, methods were revived.[15]

Nazi architecture was, both in appearance and symbolically, intimidating, an instrument of conquest. Total architecture was an extension of total war.[16] Speer wrote in 1978 "My architecture represented an intimidating display of power".

The airport halls of Tempelhof International Airport built by Nazi architect Ernst Sagebiel are still known as the largest built entities worldwide.[citation needed] The colossal dimensions of Roman and Nazi buildings also served to emphasize the insignificance of the individual engulfed in the architectural vastness of a state building. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau's reactions on visiting the Pont du Gard in 1737 produced in him the response that Hitler hoped for Berlin, to impress with its grandeur.

Architecture as religion

A major difference between the neoclassical state architecture of Nazi Germany and neoclassical architecture in other modern countries in Europe and America is that in Germany it was but one facet of a severely authoritarian state. Its dictator aimed to establish architectural order; gridiron town plans, axial symmetry, hierarchical placement of state structure within urban space on a scale intended to reinforce the social and political order desired by the Nazi state, which anticipated the displacement of Christian religion and ethical values by a new kind of worship based on the cult of Nazi martyrs and leaders and with a value system close to that of pre-Christian Rome.

The first Nazi forum, Königsplatz in Munich, was planned in 1931-32 by Hitler and his architect Paul Ludwig Troost, whom Speer says Hitler regarded as the greatest German architect since Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Troost had already redecorated the interior of the so-called Brown House on Brienner Strasse in 1930 after its acquisition by the Nazi party (Lehmann-Haupt 113). Troost, who like his successor, Speer, aimed to revive an early classical or Doric architecture, could not have found a more encouraging context for his endeavours than the neo classical architectural setting of Königsplatz. However, like Hitler, he found Bauhaus architecture distasteful, the Ehrentempel he designed was not uninfluenced by modernist tendencies, in no respect were his temples conventionally Doric. In the summer of 1931 Troost prepared drawings for four party buildings that were to be erected at the east end of the forum, symmetrically placed along Arcisstrasse. The Nazi literature of the period leaves little doubt that this new forum was regarded as a sacred cult centre, which was even referred to as "Acropolis Germainiae".

Koenigsplatz was labeled the "Forum of the Movement" in reference to the birthplace of the Nazi Party. Hitler had then believed that the German cities "lacked the monumental urban spaces and structures required to build and maintain a sense of community," and therefore moulded Koenigsplatz according to rectify these shortcomings. Previous to the redesign, Koenigsplatz lacked an eastern wall, which contradicted the ideas of community and solidarity. The eastern wall was added by the Party, and thus the new square was deemed a completion of the old square instead of a complete re-establishment.

Priority was given to the erection of two "martyrs" temples of identical shape named the Ehrentempel, placed just to either side of the square's long axis. The Ehrentempel were demolished by the US Army in 1947.

In 1935, Hitler said the martyrs' bodies were not to be buried out of sight in crypts, but should be placed in the open air, to act as eternal sentinels for the German nation. Hitler later insisted on this detail when Hermann Giesler planned the Volkshalle for Weimar's forum. He asked his architect to ensure that the two crypts, which were to contain the bodies of Brown Shirts SA killed in Thuringia, which were to placed at the entrance to the Volksahlle, be lit by open oculi.[17] It is interesting too that later still 1940 Hitler asked Giesler to plan his own mausoleum in Munich in such a way that his sarcophagus would be exposed to sun and rain.[18] It is worth noting that in Hitler's will of May 2, 1938, written the day before he left Germany for his state visit to Rome, Hitler instructed that his body was to be put in a coffin similar to that of the other martyrs and placed in the Ehrentempel next to the Führerbau.

Troost's temples in Königsplatz were thus regarded as guard posts, a notion reinforced by the presence of SS sentinels who stood guard at the entrance of each temple. A year earlier Hitler had said that the blood of the martyrs was to be the baptismal water (Gr.Taufwasser) of the Third Reich. Such imagery perhaps disturbed devout Christians, yet it left no doubt that the cult of Nazi heroes was to replace the worship of Christian martyrs. This objective was demonstrated in another way: No Nazi forum planned for any German city was to incorporate a new church. Indeed, a cathedral (Gr.Quedlinburg) was turned into a shrine by the SS, who planned to treat the cathedrals of Brunswick and Strasbourg in the same way; in Munich a church was demolished to make way for new Nazi buildings.[19] Yet, overseas the impression was created that the building of new churches was an integral part of the new Nazi building program. Temples for martyrs were given pride of place, as at Königsplatz or, as at the Weimar forum, martyrs' crypts at the entrance of the Volkshalle were given prominence.[20]

On September 6, 1938, Hitler made his position clear about the attitude of the Nazis toward religion. He said that in its purpose National Socialism had no mystic cult, only the care and leadership of a people defined by a common blood relationship. He continued with the remark that Nazis had no rooms for worship but only halls for the people (that is, no churches, but Volkshallen) no open spaces for worship, but spaces for assemblies and parades (Gr.Aufmarschplätze). Nazis had no religious retreats, only sports arenas and playing fields (Gr.Stadia) and the characteristic feature of Nazi places of assembly was not the mystical gloom of a cathedral, but the brightness and light of a room or hall that combined beauty with fitness for its purpose. Three days prior to making this statement, which relates precisely to the functions of Nazi state building plans and types, Hitler had stated that worship for Nazis was exclusively the cultivation of the natural (that is, the Dionysiac). In addition, Alfred Rosenberg made it clear that Nazism and the Christian Church were incompatible.

However, Hitler's model was that of a Roman Catholic church. The mysticism of Christianity, created buildings with a mysterious gloom which made men more ready to submit to the renunciation of self.[21] Hitler was deeply impressed by the organization, ritual and architecture of the church. In writing of the spell which an orator can weave over an audience, Hitler stated:

The same purpose is served by the artificial and yet mysterious twilight in Catholic churches.[22]

He might have envied the powerful influence, which the church exerted on the masses, for on one occasion Hitler declared:

the concluding meeting in Nuremberg must be exactly as solemnly and ceremonially performed as a service of the Catholic Church".[23]

Whereas the Nazi buildings should reflect the devout spirit of the movement, there was no place for mysticism in them. Hitler stated once that Nazism was cool-headed and realistic. It "mirrored scientific knowledge". It was "not a religious cult". Hitler noted that the Nazi party had no religious retreats and no rooms for worship with the mystical gloom of the cathedral but rather halls for the Volk[24]

Thus, the huge Volkshalle was to dominate Berlin's new forum and north-south axis, whereas at EUR the new Church of the Saints Paul and Peter dominated the new town's decumanus. Its dome is the second largest in Rome after that of St. Peter's Basilica, whereas the dome of Saint Peter's would have fitted through the oculus in the dome of the Berlin Volkshalle. No two buildings could better illustrate the differences between Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy with respect to Christian worship. Fascist Italy incorporated Rome of the Caesars and of the Popes. Nazi Germany espoused only the values of pagan Rome where Christians who flouted the cult of the emperor were penalized. The globe on the lantern of St. Peter's Basilica is surmounted by a cross. The globe of the world, which was to be placed on the lantern of the Berlin Volkshalle, was firmly gripped in the talons of an imperial eagle, which were also Reichsadler and the attribute of Zeus/Jupiter. The political theme of a globe gripped by an eagle was rendered in bronze by the sculptor Ernst Andreas Rauch for the exhibition of art in the House of German Art in 1940.[20]

Not only were churches excluded from the new fora but also so was the town hall (Gr.Rathaus) since the mayor (Gr.Bürgermeister) yielded to the Führer as the representative of local community and nation. This was an essential feature of the leader principle (Gr.Führerprinzip).[25]

In the Nuremberg Party Rallies, leader and led met together and everyone was filled with wonder at the event, in one of Hitler's Nuremberg speeches he stated, "Not every one of you sees me and I do not see every one of you. But I feel you and you feel me!".[26]

A notable feature of these rallies was that they were often held at night with spectacular light effects, such as powerful search lights, creating pillars of white light many kilometres long around the perimeter of an assembly ground. The effect of such a contrivance was described as a "Cathedral of Light" (Gr. Lichtdom). The term is most appropriate, since Hitler had already stated in Mein Kampf[27] that the Church in its wisdom had studied the psychological appeal made upon worshippers by their surroundings: the use of artificially produced twilight casting its secret spell upon the congregation, as well as incense and burning candles. If the National Socialist speaker were to study the psychology of these effects, it would be beneficial. The lighting effects in Nuremberg, particularly at the Zeppelinfeld stadium, owed nothing to chance. The congregationalizing of Nazi souls in assembly buildings needed a suitable political framework to make it possible.

Theory of Ruin Value

The "Theory of Ruin Value" (Gr. Ruinenwerttheorie) was conceived by Albert Speer, who recommended that, in order to provide a "bridge to tradition" to future generations, modern "anonymous" materials such as steel girders and ferroconcrete should be avoided in the construction of monumental party buildings wherever possible, since such materials would not produce aesthetically acceptable ruins. Thus the most politically significant buildings of the Reich would to some extent, even after falling into ruins after thousands of years, resemble their Roman models. The quarries of the Reich could not supply enough granite and marble to build Hitler's monuments for posterity. Consequently, vast quantities of granite and marble were ordered from quarries in Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Norway, France and Italy.[28][29]

In Mein Kampf,[30] Hitler had stressed the need for increased expenditure on public buildings that in terms of durability and aesthetic appeal would match the opera publica of the ancient world.

After the total collapse of the Third Reich in 1945, one of Speer's major state buildings, the new Chancellery in Berlin, did not become an aesthetic ruin but was treated like the monuments of ancient Rome after its political collapse. For example, the Russians demolished the hated Machtzentrum of the Führer in 1947; the marble that had once decorated the representative rooms of the palace was reused to build a Soviet war memorial in East Berlin's Treptower Park and to construct the Thälmann-Platz[31] and the Mohrenstraße [32] U-Bahn stations .

Hitler's mausoleum

During Hitler's tour of Paris in June 1940 he visited Les Invalides, where he stood silently gazing upon Napoleon's tomb.[33] But it was the classical Pantheon in Rome and its perfect shape that impressed Hitler during his visit in the Italian Capital in 1938.[citation needed] In late 1940, Hitler advised Giesler about the Pantheon and the mausoleum he wanted to build.

"Imagine to yourself, Giesler, if Napoleon's sarcophagus were placed beneath a large oculus, like that of the Pantheon".[34] He goes on to express an almost mystical delight in the thought that the sarcophagus would be exposed to darkness and light, rain and snow and thus be linked directly to the universe.

Thus, Hitler decided on a mausoleum, the design of which was based on that of the Pantheon, not in its original function as a temple but in its later function as a tomb of the famous: the artist Raphael and the kings Victor Emannuel II and Umberto I.[35]

The mausoleum was to be connected to the Halle der Partei at Munich by a bridge over Gabelsbergerstrasse, to become a party-political cult centre in the city regarded by Hitler as the home of the Nazi party. The dimensions were slightly smaller than the Pantheon. The oculus in the centre of the dome was to be one metre wider in diameter than that of the Pantheon (8.92 metres) to admit more light on Hitler's sarcophagus, placed immediately under it on the floor of the rotunda. The modest dimensions of the structure and its lack of rich decoration are at first sight puzzling in light of Hitler's predilection for gigantic dimensions, but in this case the focal point of the building was the Führer's sarcophagus, which was not to be dwarfed by dimension out of all proportion to the size of the sarcophagus itself. Likewise, rich interior decoration would have distracted the attention of "pilgrims". Giesler's scale model of the building apparently pleased Hitler, but the model and plans, kept by Hitler in the Reichskanzlei, are now probably in the hands of the Russians or have been destroyed.[36] It was perhaps because Hitler was so pleased with the design of his own mausoleum that in late autumn 1940 he asked Giesler to design a mausoleum for his parents in Linz. Giesler gives no details of the structure, but it is clear from the photograph of his model that once more Hadrian's Pantheon was the model.

Sculpture

Sculpture was used as part of, and in conjunction with, Nazi architecture to embody the "German Spirit" of divine destiny. Sculpture expressed the National Socialist obsession with the ideal body and espoused nationalistic, state approved values like loyalty, work, and family. Josef Thorak and Arno Breker were the most famous sculptors of the Nazi regime.

Arno Breker was in a certain sense both the best and the worst of the Nazi artists. Nominated as official state sculptor on Hitler's birthday in 1937, his technique was excellent, and his choice of subject, poses, theme were outstanding. Breker uses his numerous "naked men with swords" to unite the notions of health, strength, competition, collective action and willingness to sacrifice the self for the common good seen in many other Nazi works with explicit glorification of militarism.[citation needed]

Labour and plunder

The number of skilled and unskilled workers required to erect Hitler's increasingly gigantic buildings created a labour problem. When he assumed power in 1933, there were still many unemployed workers in Germany, some of whom were given work on public building schemes that Hitler thought would stimulate a sluggish German economy and at the same time provided him with popular propaganda "Hitler Creates Jobs" (Gr Hitler schafft Arbeit). The majority of the unemployed were quickly absorbed by the armaments factories and not by the construction industry, as Nazi propaganda suggested.[37]

However, the unemployed did not always thank Hitler for their employment; German workers employed on the building of the autobahns repeatedly went on strike from 1934 onward because of their atrocious working conditions, which led to graffiti such as "Adolf Hitler's roads are built with the blood of German workers". The Gestapo was ruthlessly used for strike-breaking and recalcitrant workers were sent to concentration camps on the assumption that they were communists.[38]

As preparations for war and later as the demands of war absorbed increasingly larger quantities of steel, concrete and manpower, the state building program slowed down to the point where in 1943 all work virtually came to a halt at the Nuremberg rally grounds.[39]

New quarries within Germany and Austria were established by the SS, who set up concentration camps such as Mauthausen, Flossenbürg, Natzweiler and Gross-Rosen,[28] where inmates were forced to quarry stone for Hitler's buildings. The inmates were to be given minimal, low-cost diets, in which Himmler took a special interest. On March 23, 1942, Himmler asked Oswald Pohl "to gradually develop a diet which, like that of Roman soldiers or Egyptian slaves, contains all the vitamins and is simple and cheap".

Plans were also made to import three million slavic peoples into Germany to work for twenty years on the Reich's building sites.[40] By May 1941 more than three million people were being forced to work in Germany and of these a third were prisoners of war and the rest of the people forcibly removed from conquered territories.[41]

This use of forced slave labour and the massive expenditure of funds on buildings commissioned by an autocrat under no constraint to disclose or justify such an expenditure, invites comparison with Roman methods of paying for and erecting the opera publica.[42]

Rome's vast state buildings, admired and envied by Hitler, could be built only because Roman imperialism over a period of centuries generated the wealth and made available the manpower to pay for and erect the structures that enhanced the "sovereign power of the Roman people or the emperor" (Lt Maiestas) and spread the propaganda of the emperor. In Rome public buildings were customarily paid for out of plunder (Lt Manubiae) derived from foreign wars. For example, Trajan's vast forum was financed from booty derived from his Dacian wars. Julius Caesar's grandiose building plans, partly put into effect after his death by Augustus, were made possible thanks to the plunder he had gained from his wars in Gaul. The acquisition of works of art for the embellishment of private and public buildings was also frequently based on plunder. Here one can point to the aftermath of the sack of Corinth by Lucius Mummius Achaicus in 146 B.C., when shiploads of art treasures were sent to Rome. So too Hitler "collected" works of art from all conquered territories for eventual exhibition in the vast gallery that was to have been built in Linz.[43]

The use of forced labour on building sites both in Rome and in the provinces was a normal Roman practice. Thus, buildings like the Congress Hall in Nuremberg and the Volkshalle in Berlin, inspired by the Colosseum and the Pantheon, respectively, were not merely symbols of tradition, order and reliability, but signaled a far more sinister intention on the part of the autocrat who commissioned them: a return to Roman ethics, which recognized the natural right of a conqueror to enslave conquered peoples in the most literal sense of the word, a right already made manifest even within the sphere of architecture by the creation of concentration camps, whose inmates were forced to quarry the stone for the Reich's buildings.[44]

Thus, it seems clear that Hitler's grandiose plans for the architectural embellishment of Berlin and Germany's regional capitals could have been achieved only by using the same methods as those employed by the Romans: forcible acquisition of funds and forced labour.[42]

See also

General

Nazi construction

|

|

|

Hitler's builders

References

- ↑ Scobie 92

- ↑ Scobie 80

- ↑ Speer, Third Reich, 75-76

- ↑ Speer, pp. 93-4

- ↑ Taylor 13

- ↑ Schmitz

- ↑ Scobie 133-134

- ↑ Petsch 112

- ↑ Scobie 134

- ↑ Hitler, Table Talk, 146

- ↑ Taylor

- ↑ Scobie 136

- ↑ Krier 219

- ↑ Taylor 250-269

- ↑ Scobie 41

- ↑ Lehmann-Haupt 111

- ↑ Giesler 121

- ↑ Giesler 116-117

- ↑ Thies, Hitlers Stadte, 60

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Scobie 65

- ↑ Baynes 577

- ↑ Mein Kampf p. 475

- ↑ Zoller 193

- ↑ Taylor 33

- ↑ Petsch 82

- ↑ Baynes 197

- ↑ Mein Kampf pg. 532

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Thies, Weltherrschaft, 100

- ↑ Scobie 94

- ↑ Mein Kampf 1.10

- ↑ Scobie 95-96

- ↑ Roland Harder: Reichskanzlei

- ↑ Spotts 327

- ↑ Giesler 31

- ↑ Scobie 116

- ↑ Giesler 35

- ↑ Lärmer 52-55

- ↑ Lärmer 54

- ↑ Schönberger 164-166

- ↑ Thies, Nazi Architecture, 58

- ↑ Homze 68

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Scobie 131

- ↑ De Jaeger 52-56

- ↑ Scobie 137

Further reading

Books

- Baynes, Norman H. The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, April 1922-August 1939, V1 & V2. London: Oxford University Press, 1942. V1 - ISBN 0-598-75893-3 V2 - ISBN 0-598-75894-1

- Cowdery, Ray and Josephine. The New German Reichschancellery in Berlin 1938-1945

- De Jaeger, Charles. The Linz File, New York: Henry Holt & Co, 1982. ISBN 0-03-061463-5.

- Giesler, Hermann. Ein Anderer Hitler: Bericht Seines Architekten Erlebnisse, Gesprache, Reflexionen, 2nd Edition (Illustrated), Druffel, 1977. ISBN 3-8061-0820-X.

- Helmer, Stephen. Hitler's Berlin: The Speer Plans for Reshaping the Central City (Illustrated). Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1985. ISBN 0-8357-1682-1.

- Hitler, Adolf. Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944: His Private Conversations, 3rd Edition. New York: Enigma Books, 2000. ISBN 1-929631-05-7.

- Homze, Edward L. Foreign Labor in Nazi Germany. New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1967. ISBN 0-691-05118-6.

- Jaskot, Paul. The Architecture of Oppression: The SS, Forced Labor and the Nazi Monumental Building Economy. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Krier, Leon. Albert Speer Architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1989. ISBN 2-87143-006-3.

- Lärmer, Karl. Autobahnbau in Deutschland 1933 bis 1945. Berlin: 1975.

- Lehmann-Haupt, Hellmut. Art under a Dictatorship (Illustrated). New York: Octagon Books, 1973. ISBN 0-374-94896-8.

- Lehrer, Steven. The Reich Chancellery and Fuhrerbunker Complex

- Petsch, Joachim. Baukunst Und Stadtplanung Im Dritten Reich: Herleitung, Bestandsaufnahme, Entwicklung, Nachfolge (Illustrated). C. Hanser, 1976. ISBN 3-446-12279-6.

- Rittich, Werner, Architektur und Bauplastik der Gegenwart, published by Rembrandt-Verlag G.M.B.H., Berlin, 1938

- Schönberger, Angela. Die Neue Reichskanzlei Von Albert Speer, Berlin: Mann, 1981. ISBN 3-7861-1263-0.

- Scobie, Alexander. Hitler's State Architecture: The Impact of Classical Antiquity. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-271-00691-9.

- Schmitz, Matthias. A Nation Builds: Contemporary German Architecture. New York: German Library of Information, 1940.

- Speer, Albert. Inside The Third Reich. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970. ISBN 0-02-037500-X.

- Spotts, Frederic. Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58567-345-5

- Taylor, Robert. Word in Stone: The Role of Architecture in the National Socialist Ideology. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974. ISBN 0-520-02193-2.

- Thies, Jochen. Hitlers Stadte: Baupolitik Im Dritten Reich E. Dokumentation (Illustrated). Wird verschickt aus, Germany: Böhlau Köln, 1978. ISBN 3-412-03477-0.

- Thies, Jochen. Architekt der Weltherrschaft. Die Endziele Hitlers. 1982. ISBN 3-7700-0425-6.

- Zoller, Albert von. Hitler privat, 1949. ISBN B0000BPY63.

Documentaries

- Adams,R.J. Ruins of the Reich, History Quest Video 2006.

- This film takes viewers on a then and now tour of the various Nazi sites such as Tannenberg Memorial, Hindenburg's Neudeck Estate, Maginot Line, big guns batteries of The Atlantic Wall, U-boat Submarine pens, Hitler's campaign headquarters of Wolfsschanze and Wolfsschlucht 2, Obersalzberg, Nazi party rally grounds, D-Day landing beaches of the Normandy campaign, Ardennes, scene of the infamous battle of the Bulge. Archival film is 1st generation 35mm film from the Nazi Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, as well as current footage of each site as they appear today. English, DVD, 4 discs, 232 minutes.

- Adams,R.J.. Order Castles of the Third Reich, History Quest Video, 2006.

- this production captures the mystic Teutonic fortresses of Nazi Germany. The inside look at the Third Reich's secretive Order Castles of Hitler's political soldiers, Hitler Youth and SS. DVD, English, 60 minutes

- Goebbels, Joseph. Hitler's Constructions/Die Bauten von Adolf Hitler (propaganda film), International Historic Films, 1938.

- This propaganda film shows the varieties of National Socialist constructions: youth hostels and party schools, bridge projects and the Autobahn, ministries and party buildings, as well as the famous monumental works, such as the Zeppelinfeld at Nuremberg. German language, English subtitles; , 17 minutes.

- This film analyzes the aesthetics created and envisioned by Adolf Hitler and the top echelon of the Third Reich. Using never-before-seen footage, the film attempts to shed light on the Nazis obsession with concepts of order and stability borrowed from ancient Greece and Rome. The film also attempts to show how the Nazi aesthetic led to the banning of such modern artists as Picasso. This disturbing film documents the Nazi philosophy of beauty through violence, highlighting Hitler's views on culture, art and architecture. Includes exclusive archival footage of the last days of the Third Reich, with film shot inside Hitler's bunker.

- Kiefer, Kent. Ruins of the Third Reich, Kiefer Entertainment, 2005.

- This film was shot in 1947 by an American industrialist and covers the destruction of the Third Reich in World War II. Many of the Nazi Party's most sacred and important sites appear in this film in total ruins. Included is rare and never before seen footage of Hitler's bunker, the Reich Chancellery, Hitler's office, Nuremberg rally sites and much more. Included is footage of Goebbels residence after being partially destroyed by Russian gunfire, Luftwaffe Administrative Headquarters (Post War American Military Government H.Q.), the Reichstag and the Berlin Victory Column that Hitler had raised by 30 feet (9 meters). Also seen is the Olympic Stadium where the 1936 Summer Olympics took place, the Krupp Steelworks in Essen, the former Krupp Estate (British Administrative H.Q.), the ruins of Cologne, a trip up the Rhine, the Nuremberg Palace of Justice and the Munich beer garden Burger Brau Keller where Hitler's career began. This film is a fascinating historical document and time capsule depicting the aftermath of Germany's destruction in World War II.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nazi architecture. |

Articles

- A Theory of Ruin-value , Cornelius Holtorf, last updated on 21 December 2004.

Graphics

Misc

- Axis History Forum: Architecture

- Third Reich In Ruins

- Flaktuerme

- NS-Architektur at Lebendiges Museum Online. (German)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)