Saint Naum

| Saint Naum | |

|---|---|

Icon of Saint Naum | |

| Wonderworker, Apostle of the Slavs | |

| Born | ca. 830 |

| Died |

December 23, 910 Ohrid, Bulgarian Empire, (present-day Republic of Macedonia) |

| Honored in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Monastery of Saint Naum in Ohrid (Sveti Naum) |

| Feast | 5 January and 3 July (Julian calendar), 20 May and 23 December (Revised Julian calendar) |

| Patronage | People with mental disorders and/or other illnesses |

Saint Naum (Bulgarian: Свети Наум, Sveti Naum), also known as Naum of Ohrid or Naum of Preslav (c. 830 – December 23, 910) was a medieval missionary among the Slavs, who became later an Bulgarian enlightener.[1][2][3][4][5] He was among the disciples of Saints Cyril and Methodius and is associated with the creation of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts. Naum was among the founders of the Pliska Literary School and is venerated as a saint in the Orthodox Church.

Biography

Information about his early life is scarce. According to the hagiography of Saint Cyril and Methodius by Clement of Ohrid, Naum took part in the historic mission to Great Moravia together with Cyril, Methodius, Clement, Angelarius, Gorazd and other Slavic missionaries in 863.[6]

Great Moravia and Lower Panonia

For the next 22 years, he worked with Cyril and Methodius and other missionaries in translating the Bible into Old Church Slavonic and promoted it in Great Moravia and Principality of Lower Pannonia. In 867 or 868 he became a priest in Rome. For the purpose of the mission to Moravia, the missionaries devised the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet to match the specific features of the Slavic language. Its descendant script, Cyrillic, is still used by many languages today. The missionaries also wrote the first Slavic Civil Code, which was used in Great Moravia. However, the missionary work ran into opposition from German clerics who opposed their efforts to create a Slavic liturgy. By 885, the two main patrons for the missionaries, Rastislav of Moravia of Great Moravia and Prince Koceľ of Pannonia, as well as Cyril and Methodius had died, and the pressure from the German church became increasingly more hostile. After a brief period of imprisonment due to the ongoing conflict with the German clerics, Naum, together with some of the missionaries headed to Bulgaria.

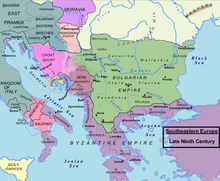

Bulgaria

In 886 the governor of Belgrade, then in Bulgaria, welcomed the disciples of Cyril and Methodius. The kingdom was ruled then by Tsar Boris, who converted to Christianity in 864. After the christianization the religious ceremonies were conducted in Greek by a Byzantine clergy. Fearing growing Byzantine influence Boris viewed the adoption of the Old Church Slavonic as a way to preserve the political independence of Bulgaria. With a such views Boris made arrangements for the establishment of two literary academies where theology was to be taught in the Slavonic language. The first of the schools was founded in the capital, Pliska, and the second in Ohid, in the region of Kutmichevitsa. The development of Old Church Slavonic literacy had the effect of preventing the assimilation into the neighboring cultures and promoted the formation of a distinct Bulgarian identity.[7][8] Naum moved initially to the capital Pliska together with Clement, Angelarius and possibly Gorazd (according to other sources, Gorazd was already dead by that time). In Bulgaria he spent the next 25 years from his life. Naum was one of the founders of the Pliska Literary School where he worked between 886 and 893. The most reliable first-hand account of the activities at the time in Pliska is "An Account of Letters" (O pismenech), a treatise on Slavic literacy written in Old Church Slavonic, thought to be composed shortly after 893. The piece calls for the creation of a common Slavic alphabet. In 893, shortly after his rise to power, the new Bulgarian ruler Simeon the Great, summoned an ecclesiastical council in the new capital Preslav, where Clement was ordained bishop of Drembica and Velika. To replace Clement in Ohrid, Simeon sent Naum, who until then had been active in Preslav. Afterwards Naum continued Clement's work at Ohrid, another important centre of Slavic learning. In this years the Cyrillic script was created in the Preslav literrary school,[9] and was adopted in Bulgaria, possibly following Naum's initiative.[10] In 905 Naum founded a monastery on the shores of Lake Ohrid, which later received his name. He died there in 910 and Clement initiated the process of his canonization.[11] In this way Naum became the first “native” saint of Bulgaria.[12]

Legacy

St. Naum Peak on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named for Saint Naum.

External links

Житие на Свети Наум; Жития на светиите. Синодално издателство, София, 1991 година, под редакцията на Партений, епископ Левкийски и архимандрит д-р Атанасий (Бончев). In English: Life of St. Naum, Vitaes of the Saints. St. Synod Publishing, Sofia, 1991, edited by Parthenios, Bishop Levkiyski and Archimndrite Dr. Athanasios (Bonchev).

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Naum. |

References

- ↑ The early medieval Balkans: a critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century, John Van Antwerp Fine, University of Michigan Press, 1991, ISBN 0-472-08149-7, p. 128.

- ↑ Obolensky, Dimitri (1994). Byzantium and the Slavs. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 0-88141-008-X.

- ↑ Monks and Laymen in Byzantium, 843-1118, Rosemary Morris, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-31950-1, p. 25.

- ↑ Historical dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, imitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0-8108-5565-8, p. 159.

- ↑ The national question in Yugoslavia: origins, history, politics, Cornell Paperbacks: Slavic studies, history, political science, Ivo Banac, Cornell University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-8014-9493-1, p. 309.

- ↑ Kantor, Marvin (1983). Medieval Slavic Lives of Saints and Princes. The University of Michigan Press. p. 65.

- ↑ Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1-85065-534-0, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ A short history of modern Bulgaria, R. J. Crampton, CUP Archive, 1987, ISBN 0521273234, p. 5.

- ↑ Curta, Florin, Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521815398, pp. 221–222.

- ↑ The A to Z of the Orthodox Church, Michael Prokurat, Alexander Golitzin, Michael D. Peterson, Rowman & Littlefield, 2010, ISBN 0810876027 p. 91.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Byzantium, John H. Rosser, Scarecrow Press, 2012, ISBN 0810875675, p. 342.

- ↑ Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250, Florin Curta,Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521815398, p. 214.