Napoleon points

In geometry, Napoleon points are a pair of special points associated with a plane triangle. It is generally believed that the existence of these points was discovered by Napoleon Bonaparte, the Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815, but many have questioned this belief.[1] The Napoleon points are triangle centers and they are listed as the points X(17) and X(18) in Clark Kimberling's Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers.

The name "Napoleon points" has also been applied to a different pair of triangle centers, better known as the isodynamic points.[2]

Definition of the points

First Napoleon point

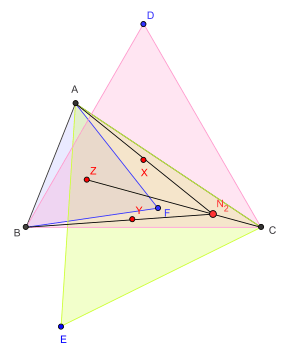

Let ABC be any given plane triangle. On the sides BC, CA, AB of the triangle, construct outwardly drawn equilateral triangles DBC, ECA and FAB respectively. Let the centroids of these triangles be X, Y and Z respectively. Then the lines AX, BY and CZ are concurrent. The point of concurrence N1 is the first Napoleon point, or the outer Napoleon point, of the triangle ABC.

The triangle XYZ is called the outer Napoleon triangle of the triangle ABC. Napoleon's theorem asserts that this triangle is an equilateral triangle.

In Clark Kimberling's Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers, the first Napoleon point is denoted by X(17).[3]

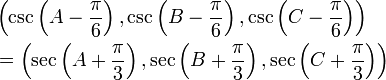

- The trilinear coordinates of N1:

- The barycentric coordinates of N1:

Second Napoleon point

Let ABC be any given plane triangle. On the sides BC, CA, AB of the triangle, construct inwardly drawn equilateral triangles DBC, ECA and FAB respectively. Let the centroids of these triangles be X, Y and Z respectively. Then the lines AX, BY and CZ are concurrent. The point of concurrence N2 is the second Napoleon point, or the inner Napoleon point, of the triangle ABC.

The triangle XYZ is called the inner Napoleon triangle of the triangle ABC. Napoleon's theorem asserts that this triangle is an equilateral triangle.

In Clark Kimberling's Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers, the second Napoleon point is denoted by X(18).[3]

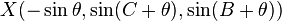

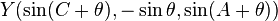

- The trilinear coordinates of N2:

- The barycentric coordinates of N2:

Generalizations

The results regarding the existence of the Napoleon points can be generalized in different ways. In defining the Napoleon points we begin with equilateral triangles drawn on the sides of the triangle ABC and then consider the centers X, Y, and Z of these triangles. These centers can be thought as the vertices of isosceles triangles erected on the sides of triangle ABC with the base angles equal to π/6 (30 degrees). The generalizations seek to determine triangles with less restrictive conditions which, when erected over the sides of the triangle ABC, are such that the lines joining their external vertices and the vertices of triangle ABC are concurrent.[citation needed]

Generalization to isosceles triangles

This generalization asserts the following:[4]

- If the three triangles XBC, YCA and ZAB, constructed on the sides of the given triangle ABC as bases, are similar, isosceles and similarly situated, then the lines AX, BY, CZ concur at a point N.

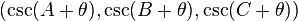

If the common base angle is  , then the vertices of the three triangles have the following trilinear coordinates.

, then the vertices of the three triangles have the following trilinear coordinates.

The trilinear coordinates of N

A few special cases are interesting.

Value of

The point

0 G, the centroid of triangle ABC π /2 ( or, – π /2 ) O, the orthocenter of triangle ABC π /3 N1, the first Napoleon point – π /3 N2, the second Napoleon point – A ( if A < π /2 )

π – A ( if A > π /2 )The vertex A – B ( if B < π /2 )

π – B ( if B > π /2 )The vertex B – C ( if C < π /2 )

π – C ( if C > π /2 )The vertex C

Moreover, the locus of N as the base angle  varies between -π/2 and π/2 is the conic

varies between -π/2 and π/2 is the conic

This conic is a rectangular hyperbola and it is called the Kiepert hyperbola in honor of Ludwig Kiepert (1846–1934), the mathematician who discovered this result.[4] This hyperbola is the unique conic which passes through the five points A, B, C, G and O.

Further generalizations

Generalization to similar (not necessarily isosceles) triangles

The three triangles XBC, YCA, ZAB erected over the sides of the triangle ABC need not be isosceles for the three lines AX, BY, CZ to be concurrent.[5]

- If similar triangles XBC, AYC, ABZ are constructed outwardly on the sides of any triangle ABC then the lines AX, BY and CZ are concurrent.

Generalization to arbitrary (not necessarily similar) triangles

The concurrence of the lines AX, BY, and CZ holds even in much relaxed conditions. The following result states one of the most general conditions for the lines AX, BY, CZ to be concurrent.[5]

- If triangles XBC, YCA, ZAB are constructed outwardly on the sides of any triangle ABC such that

- ∠CBX = ∠ABZ, ∠ACY = ∠BCX, ∠BAZ = ∠CAY,

- then the lines AX, BY and CZ are concurrent.

On the discoverer of Napoleon points

Coxeter and Greitzer state the Napoleon Theorem thus: If equilateral triangles are erected externally on the sides of any triangle, their centers form an equilateral triangle. They observe that Napoleon Bonaparte was a bit of a mathematician with a great interest in geometry. However, they doubt whether Napoleon knew enough geometry to discover the theorem attributed to him.[1]

The earliest recorded appearance of the result embodied in Napoleon's theorem is in an article in The Ladies' Diary appeared in 1825. The Ladies' Diary was an annual periodical which was in circulation in London from 1704 to 1841. The result appeared as part of a question posed by W. Rutherford, Woodburn.

- VII. Quest.(1439); by Mr. W. Rutherford, Woodburn." Describe equilateral triangles (the vertices being either all outward or all inward) upon the three sides of any triangle ABC: then the lines which join the centers of gravity of those three equilateral triangles will constitute an equilateral triangle. Required a demonstration."

However, there is no reference to the existence of the so-called Napoleon points in this question. Christoph J. Scriba, a German historian of mathematics, has studied the problem of attributing the Napoleon points to Napoleon in a paper in Historia Mathematica.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Coxeter, H. S. M.; Greitzer, S. L. (1967). Geometry Revisited. Mathematical Association of America. pp. 61–64.

- ↑ Rigby, J. F. (1988). "Napoleon revisited". Journal of Geometry 33 (1–2): 129–146. doi:10.1007/BF01230612. MR 963992.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kimberling, Clark. "Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers". Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Eddy, R. H.; Fritsch, R. (June 1994). "The Conics of Ludwig Kiepert: A Comprehensive Lesson in the Geometry of the Triangle". Mathematics Magazine 67 (3): 188–205. doi:10.2307/2690610. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 de Villiers, Michael (2009). Some Adventures in Euclidean Geometry. Dynamic Mathematics Learning. pp. 138–140. ISBN 9780557102952.

- ↑ Scriba, Christoph J (1981). "Wie kommt 'Napoleons Satz' zu seinem namen?". Historia Mathematica 8 (4): 458–459. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(81)90054-9.

Further reading

- Stachel, Hellmuth (2002). "Napoleon's Theorem and Generalizations Through Linear Maps". Contributions to Algebra and Geometry 43 (2): 433–444. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Grünbaum, Branko (2001). "A relative of "Napoleon's theorem"". Geombinatorics 10: 116–121. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Katrien Vandermeulen, et al. "Napoleon, a mathematician ?". Maths for Europe. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Bogomolny, Alexander. "Napoleon's Theorem". Cut The Knot! An interactive column using Java applets. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- "Napoleon's Thm and the Napoleon Points". Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Napoleon Points". From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Philip LaFleur. "Napoleon’s Theorem". Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Wetzel, John E. (April 1992). "Converses of Napoleon's Theorem". Retrieved 24 April 2012.