Napier's bones

| Computing devices in |

| Rabdology |

|---|

| Napier's bones |

| Promptuary |

| Location arithmetic |

Napier's bones is a manually-operated calculating device created by John Napier of Merchiston for calculation of products and quotients of numbers. The method was based on Arab mathematics and the lattice multiplication used by Matrakci Nasuh in the Umdet-ul Hisab[1] and Fibonacci's work in his Liber Abaci. The technique was also called Rabdology (from Greek ῥάβδoς [r(h)abdos], "rod" and -λογία [logia], "study"). Napier published his version in 1617 in Rabdologiæ, printed in Edinburgh, Scotland, dedicated to his patron Alexander Seton.[2]

Using the multiplication tables embedded in the rods, multiplication can be reduced to addition operations and division to subtractions. More advanced use of the rods can even extract square roots. Note that Napier's bones are not the same as logarithms, with which Napier's name is also associated.

.png)

The complete device usually includes a base board with a rim; the user places Napier's rods inside the rim to conduct multiplication or division. The board's left edge is divided into 9 squares, holding the numbers 1 to 9. The Napier's rods consist of strips of wood, metal or heavy cardboard. Napier's bones are three dimensional, square in cross section, with four different rods engraved on each one. A set of such bones might be enclosed in a convenient carrying case.

A rod's surface comprises 9 squares, and each square, except for the top one, comprises two halves divided by a diagonal line. The first square of each rod holds a single digit, and the other squares hold this number's double, triple, quadruple, quintuple, and so on until the last square contains nine times the number in the top square. The digits of each product are written one to each side of the diagonal; numbers less than 10 occupy the lower triangle, with a zero in the top half.

A set consists of 10 rods corresponding to digits 0 to 9. The rod 0, although it may look unnecessary, is needed for multipliers or multiplicands having 0 in them.

Multiplication

To demonstrate how to use Napier’s Bones for multiplication, three examples of increasing difficulty are explained below.

Example 1

Problem: Multiply 425 by 6 (425 x 6 = ?)

Start by placing the bones corresponding to the leading number of the problem into the board. If a 0 is used in this number, a space is left between the bones corresponding to where the 0 digit would be. In this example, the bones 4, 2, and 5 are placed in the correct order as shown below.

Looking at the first column, choose the number wishing to multiply by. In this example, that number is 6. The row this number is located in is the only row needed to perform the remaining calculations and thus the rest of the board is cleared below to allow more clarity in the remaining steps.

Starting at the right side of the row, evaluate the diagonal columns by adding the numbers that share the same diagonal column. Single numbers simply remain that number.

Once the diagonal columns have been evaluated, one must simply read from left to right the numbers calculated for each diagonal column. For this example, reading the results of the summations from left to right produces the final answer of 2550.

Therefore: The solution to multiplying 425 by 6 is 2550. (425 x 6 = 2550)

Example 2

When multiplying by larger single digits, it is common that upon adding a diagonal column, the sum of the numbers result in a number that is 10 or greater. The following example demonstrates how to properly carry over the tens place when this occurs.

Problem: Multiply 6785 by 8 (6785x8=?)

Begin just as in Example 1 above and place in the board the corresponding bones to the leading number of the problem. For this example, the bones 6, 7, 8, and 5 are placed in the proper order as shown below.

In the first column, find the number wishing to multiply by. In this example, that number is 8. With only needing to use the row 8 is located in for the remaining calculations, the rest of the board below has been cleared for clarity in explaining the remaining steps.

Just as before, start at the right side of the row and evaluate each diagonal column. If the sum of a diagonal column equals 10 or greater, the tens place of this sum must be carried over and added along with the numbers in the diagonal column to the immediate left as demonstrated below.

After each diagonal column has been evaluated, the calculated numbers can be read from left to right to produce a final answer. Reading the results of the summations from left to right, in this example, produces a final answer of 54280.

Therefore: The solution to multiplying 6785 by 8 is 54280. (6785 x 8 = 54280)

Example 3

Problem: Multiply 825 by 913 (825 x 913 = ?)

Begin once again by placing the corresponding bones to the leading number into the board. For this example the bones 8, 2, and 5 are placed in the proper order as shown below.

When the number wishing to multiply by contains multiple digits, multiple rows must be reviewed. For the sake of this example, the rows for 9, 1, and 3 have been removed from the board, as seen below, for easier evaluation.

Evaluate each row individually, adding each diagonal column as explained in the previous examples. Reading these sums from left to right will produce the numbers needed for the long hand addition calculations to follow. For this example, Row 9, Row 1, and Row 3 were evaluated separately to produce the results shown below.

For the final step of the solution, begin by writing the numbers being multiplied one over the other, drawing a line under the second number.

825 x 913

Starting with the right most digit of the second number, place the results from the rows in sequential order as seen from right to left under each other while utilizing a 0 for place holders.

825 x 913 2475 8250 742500

The rows and place holders can then be summed to produce a final answer.

825 x 913 2475 8250 +742500 753225

In this example, the final answer produced is 753225.

Therefore: The solution to multiplying 825 by 913 is 753225. (825 x 913 = 753225)

Division

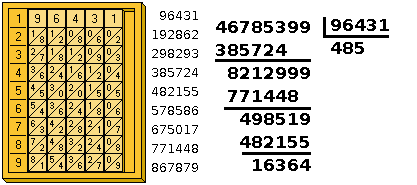

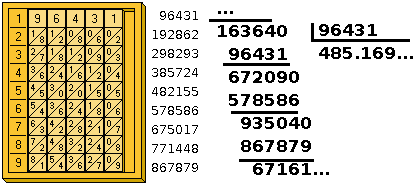

Division can be performed in a similar fashion. Let's divide 46785399 by 96431, the two numbers we used in the earlier example. Put the bars for the divisor (96431) on the board, as shown in the graphic below. Using the abacus, find all the products of the divisor from 1 to 9 by reading the displayed numbers. Note that the dividend has eight digits, whereas the partial products (save for the first one) all have six. So you must temporarily ignore the final two digits of 46785399, namely the '99', leaving the number 467853. Next, look for the greatest partial product that is less than the truncated dividend. In this case, it's 385724. You must mark down two things, as seen in the diagram: since 385724 is in the '4' row of the abacus, mark down a '4' as the left-most digit of the quotient; also write the partial product, left-aligned, under the original dividend, and subtract the two terms. You get the difference as 8212999. Repeat the same steps as above: truncate the number to six digits, chose the partial product immediately less than the truncated number, write the row number as the next digit of the quotient, and subtract the partial product from the difference found in the first repetition. Following the diagram should clarify this. Repeat this cycle until the result of subtraction is less than the divisor. The number left is the remainder.

So in this example, we get a quotient of 485 with a remainder of 16364. We can just stop here and

use the fractional form of the answer  .

.

If you prefer, we can also find as many decimal points as we need by continuing the cycle as in standard long division. Mark a decimal point after the last digit of the quotient and append a zero to the remainder so we now have 163640. Continue the cycle, but each time appending a zero to the result after the subtraction.

Let's work through a couple of digits. The first digit after the decimal point is 1, because the biggest partial product less than 163640 is 96431, from row 1. Subtracting 96431 from 163640, we're left with 67209. Appending a zero, we have 672090 to consider for the next cycle (with the partial result 485.1) The second digit after the decimal point is 6, as the biggest partial product less than 672090 is 578586 from row 6. The partial result is now 485.16, and so on.

Extracting square roots

Extracting the square root uses an additional bone which looks a bit different from the others as it has three columns on it. The first column has the first nine squares 1, 4, 9, ... 64, 81, the second column has the even numbers 2 through 18, and the last column just has the numbers 1 through 9.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | √ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/3 | 0/4 | 0/5 | 0/6 | 0/7 | 0/8 | 0/9 | 0/1 2 1 |

| 2 | 0/2 | 0/4 | 0/6 | 0/8 | 1/0 | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/6 | 1/8 | 0/4 4 2 |

| 3 | 0/3 | 0/6 | 0/9 | 1/2 | 1/5 | 1/8 | 2/1 | 2/4 | 2/7 | 0/9 6 3 |

| 4 | 0/4 | 0/8 | 1/2 | 1/6 | 2/0 | 2/4 | 2/8 | 3/2 | 3/6 | 1/6 8 4 |

| 5 | 0/5 | 1/0 | 1/5 | 2/0 | 2/5 | 3/0 | 3/5 | 4/0 | 4/5 | 2/5 10 5 |

| 6 | 0/6 | 1/2 | 1/8 | 2/4 | 3/0 | 3/6 | 4/2 | 4/8 | 5/4 | 3/6 12 6 |

| 7 | 0/7 | 1/4 | 2/1 | 2/8 | 3/5 | 4/2 | 4/9 | 5/6 | 6/3 | 4/9 14 7 |

| 8 | 0/8 | 1/6 | 2/4 | 3/2 | 4/0 | 4/8 | 5/6 | 6/4 | 7/2 | 6/4 16 8 |

| 9 | 0/9 | 1/8 | 2/7 | 3/6 | 4/5 | 5/4 | 6/3 | 7/2 | 8/1 | 8/1 18 9 |

Let's find the square root of 46785399 with the bones.

First, group its digits in twos starting from the right so it looks like this:

- 46 78 53 99

- Note: A number like 85399 would be grouped as 8 53 99

Start with the leftmost group 46. Pick the largest square on the square root bone less than 46, which is 36 from the sixth row.

Because we picked the sixth row, the first digit of the solution is 6.

Now read the second column from the sixth row on the square root bone, 12, and set 12 on the board.

Then subtract the value in the first column of the sixth row, 36, from 46.

Append to this the next group of digits in the number 78, to get the remainder 1078.

At the end of this step, the board and intermediate calculations should look like this:

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 6

-36

--

10 78 |

Now, "read" the numbers in each row, ignoring the second and third columns from the square root bone and record these. (For example, read the sixth row as : 0/6 1/2 3/6 → 756)

Find the largest number less than the current remainder, 1078. You should find that 1024 from the eighth row is the largest value less than 1078.

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 68

-36

--

10 78

-10 24

-----

54 |

As before, append 8 to get the next digit of the square root and subtract the value of the eighth row 1024 from the current remainder 1078 to get 54. Read the second column of the eighth row on the square root bone, 16, and set the number on the board as follows.

The current number on the board is 12. Add to it the first digit of 16, and append the second digit of 16 to the result. So you should set the board to

- 12 + 1 = 13 → append 6 → 136

- Note: If the second column of the square root bone has only one digit, just append it to the current number on board.

The board and intermediate calculations now look like this.

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 68

-36

--

10 78

-10 24

-----

54 53 |

Once again, find the row with the largest value less than the current partial remainder 5453. This time, it is the third row with 4089.

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 683

-36

–-

10 78

-10 24

-----

54 53

-40 89

-----

13 64 |

The next digit of the square root is 3. Repeat the same steps as before and subtract 4089 from the current remainder 5453 to get 1364 as the next remainder. When you rearrange the board, notice that the second column of the square root bone is 6, a single digit. So just append 6 to the current number on the board 136

- 136 → append 6 → 1366

to set 1366 on the board.

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 683

-36

--

10 78

-10 24

-----

54 53

-40 89

-----

13 64 99 |

Repeat these operations once more. Now the largest value on the board smaller than the current remainder 136499 is 123021 from the ninth row.

In practice, you often don't need to find the value of every row to get the answer. You may be able to guess which row has the answer by looking at the number on the first few bones on the board and comparing it with the first few digits of the remainder. But in these diagrams, we show the values of all rows to make it easier to understand.

As usual, append a 9 to the result and subtract 123021 from the current remainder.

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 6839

-36

--

10 78

-10 24

-----

54 53

-40 89

-----

13 64 99

-12 30 21

--------

1 34 78 |

You've now "used up" all the digits of our number, and you still have a remainder. This means you've got the integer portion of the square root but there's some fractional bit still left.

Notice that if we've really got the integer part of the square root, the current result squared (6839² = 46771921) must be the largest perfect square smaller than 46785899. Why? The square root of 46785399 is going to be something like 6839.xxxx... This means 6839² is smaller than 46785399, but 6840² is bigger than 46785399—the same thing as saying that 6839² is the largest perfect square smaller than 46785399.

This idea is used later on to understand how the technique works, but for now let's continue to generate more digits of the square root.

Similar to finding the fractional portion of the answer in long division, append two zeros to the remainder to get the new remainder 1347800. The second column of the ninth row of the square root bone is 18 and the current number on the board is 1366. So compute

- 1366 + 1 → 1367 → append 8 → 13678

to set 13678 on the board.

The board and intermediate computations now look like this.

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 6839.

-36

--

10 78

-10 24

-----

54 53

-40 89

-----

13 64 99

-12 30 21

--------

1 34 78 00 |

The ninth row with 1231101 is the largest value smaller than the remainder, so the first digit of the fractional part of the square root is 9.

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 6839.9

-36

--

10 78

-10 24

-----

54 53

-40 89

-----

13 64 99

-12 30 21

--------

1 34 78 00

-1 23 11 01

----------

11 66 99 |

Subtract the value of the ninth row from the remainder and append a couple more zeros to get the new remainder 11669900. The second column on the ninth row is 18 with 13678 on the board, so compute

- 13678 + 1 → 13679 → append 8 → 136798

and set 136798 on the board.

|

_____________

√46 78 53 99 = 6839.9

-36

--

10 78

-10 24

-----

54 53

-40 89

-----

13 64 99

-12 30 21

--------

1 34 78 00

-1 23 11 01

----------

11 66 99 00 |

You can continue these steps to find as many digits as you need and you stop when you have the precision you want, or if you find that the reminder becomes zero which means you have the exact square root.

Having found the desired number of digits, you can easily determine whether or not you need to round up; i.e., increment the last digit. You don't need to find another digit to see if it is equal to or greater than five. Simply append 25 to the root and compare that to the remainder; if it is less than or equal to the remainder, then the next digit will be at least five and round up is needed. In the example above, we see that 6839925 is less than 11669900, so we need to round up the root to 6840.0.

There's only one more trick left to describe. If you want to find the square root of a number that isn't an integer, say 54782.917. Everything is the same, except you start out by grouping the digits to the left and right of the decimal point in groups of two.

That is, group 54782.917 as

- 5 47 82 . 91 7

and proceed to extract the square root from these groups of digits.

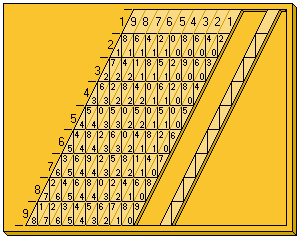

Diagonal modification

During the 19th century, Napier's bones underwent a transformation to make them easier to read. The rods began to be made with an angle of about 65° so that the triangles that had to be added were aligned vertically. In this case, in each square of the rod the unit is to the right and the ten (or the zero) to the left.

The rods were made such that the vertical and horizontal lines were more visible than the line where the rods touched, making the two components of each digit of the result much easier to read. Thus, in the picture it is immediately clear that:

- 987654321 × 5 = 4938271605

Genaille–Lucas rulers

In 1891, Henri Genaille invented a variant of Napier's bones which became known as Genaille–Lucas rulers. By representing the carry graphically, the user can read off the results of simple multiplication problems directly, with no intermediate mental calculations.

The following example is calculating 52749 × 4 = 210996.

Card abacus

_01.jpg)

In addition to the previously-described "bones" abacus, Napier also constructed a card abacus. Both devices are reunited in a piece held by the National Archaeological Museum of Spain in Madrid.

The apparatus is a box of wood with inlays of bone. In the top section it contains the "bones" abacus, and in the bottom section is the card abacus. This card abacus consists of 300 stored cards in 30 drawers. One hundred of these cards are covered with numbers (referred to as the "number cards"). The remaining two hundred cards contain small triangular holes, which, when laid on top of the number cards, allow the user to see only certain numbers. By the capable positioning of these cards, multiplications can be made up to the limit of a number 100 digits in length, by another number 200 digits in length.

In addition, the doors of the box contain the first powers of the digits, the coefficients of the terms of the first powers of the binomial and the numeric data of the regular polyhedra.[3]

It is not known who was the author of this piece, nor if it is of Spanish origin or came from a foreigner, although it is probable that it originally belonged to the Spanish Academy of Mathematics (which was created by Philip II) or was a gift from the Prince of Wales. The only thing that is sure is that it was conserved in the Palace, whence it was passed to the National library and later to the National Archaeological Museum, where it is still conserved.

In 1876, the Spanish government sent the apparatus to the exhibition of scientific instruments in Kensington, where it received so much attention that several societies consulted the Spanish representation about the origin and use of the apparatus.

See also

References

- ↑ Corlu, M. S.; Burlbaw, L. M.; Capraro, R. M.; Corlu, M. A.; Han, S. (2010). "The Ottoman Palace School Enderun and The Man with Multiple Talents, Matrakçı Nasuh". Journal of the Korea Society of Mathematical Education Series D: Research in Mathematical Education 14 (1): 19–31.

- ↑ Seton, George, Memoir of Alexander Seton, William Blackwood (1882), pp. 121-123

- ↑ Diccionario Enciclopédico Hispano-Americano, Mountainer y Simón Editores, Barcelona, 1887, Tomo I, pp. 19–20.

External links

- Java implementation of Napier bones in various number systems at cut-the-knot

- Napier and other bones and many calculators