Naphthalene

| Naphthalene | |

|---|---|

|

|

| |

| |

| IUPAC name bicyclo[4.4.0]deca-1,3,5,7,9-pentene | |

| Systematic name

| |

| Other names white tar, mothballs, naphthalin, moth flakes, camphor tar, tar camphor, naphthaline, antimite, albocarbon | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 91-20-3 |

| PubChem | 931 |

| ChemSpider | 906 |

| UNII | 2166IN72UN |

| EC number | 202-049-5 |

| KEGG | C00829 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:16482 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL16293 |

| RTECS number | QJ0525000 |

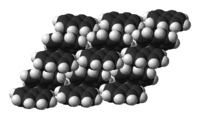

| Jmol-3D images | Image 1 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C10H8 |

| Molar mass | 128.17 g mol−1 |

| Appearance | White solid crystals/flakes, strong odor of coal tar |

| Density | 1.14 g/cm³ |

| Melting point | 80.26 °C; 176.47 °F; 353.41 K |

| Boiling point | 218 °C; 424 °F; 491 K |

| Solubility in water | Approximately 30 mg/L |

| Hazards | |

| R-phrases | R22, R40, R50/53 |

| S-phrases | (S2), S36/37, S46, S60, S61 |

| Main hazards | Flammable, sensitizer, possible carcinogen. Dust can form explosive mixtures with air |

| NFPA 704 |

2

2

0

|

| Flash point | 79 to 87 °C; 174 to 189 °F; 352 to 360 K |

| Autoignition temperature | 525 °C; 977 °F; 798 K |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| Infobox references | |

Naphthalene is an organic compound with formula C

10H

8. It is the simplest polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, and is a white crystalline solid with a characteristic odor that is detectable at concentrations as low as 0.08 ppm by mass.[1] As an aromatic hydrocarbon, naphthalene's structure consists of a fused pair of benzene rings. It is best known as the main ingredient of traditional mothballs.

History

In early 1820, two chemists, in two separate reports, described a white solid with a pungent odor derived from the distillation of coal tar. In 1821, John Kidd cited these two disclosures and then described many of this substance's properties and the means of its production. He proposed the name naphthaline, as it had been derived from a kind of naphtha (a broad term encompassing any volatile, flammable liquid hydrocarbon mixture, including coal tar).[2] Naphthalene's chemical formula was determined by Michael Faraday in 1826. The structure of two fused benzene rings was proposed by Emil Erlenmeyer in 1866,[3] and confirmed by Carl Gräbe three years later.

Structure and reactivity

A naphthalene molecule can be viewed as the fusion of a pair of benzene rings. (In organic chemistry, rings are fused if they share two or more atoms.) As such, naphthalene is classified as a benzenoid polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH). There are two sets of equivalent hydrogen atoms: the alpha positions are positions 1, 4, 5, and 8 on the drawing below, and the beta positions are positions 2, 3, 6, and 7.

Unlike benzene, the carbon–carbon bonds in naphthalene are not of the same length. The bonds C1–C2, C3–C4, C5–C6 and C7–C8 are about 1.36 Å (136 pm) in length, whereas the other carbon–carbon bonds are about 1.42 Å (142 pm) long. This difference, which was established by X-ray diffraction[citation needed], is consistent with the valence bond model of bonding in naphthalene that involves three resonance structures (as shown below); whereas the bonds C1–C2, C3–C4, C5–C6 and C7–C8 are double in two of the three structures, the others are double in only one.

Like benzene, naphthalene can undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution. For many electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions, naphthalene reacts under milder conditions than does benzene. For example, whereas both benzene and naphthalene react with chlorine in the presence of a ferric chloride or aluminium chloride catalyst, naphthalene and chlorine can react to form 1-chloronaphthalene even without a catalyst. Likewise, whereas both benzene and naphthalene can be alkylated using Friedel–Crafts reactions, naphthalene can also be alkylated by reaction with alkenes or alcohols, with sulfuric or phosphoric acid as the catalyst.

Substituted derivatives

Two isomers are possible for mono-substituted naphthalenes, corresponding to substitution at an alpha or beta position. Usually, electrophiles attack at the alpha position. The selectivity for alpha over beta substitution can be rationalized in terms of the resonance structures of the intermediate: for the alpha substitution intermediate, seven resonance structures can be drawn, of which four preserve an aromatic ring. For beta substitution, the intermediate has only six resonance structures, and only two of these are aromatic. Sulfonation, however, gives a mixture of the "alpha" product 1-naphthalenesulfonic acid and the "beta" product 2-naphthalenesulfonic acid, with the ratio dependent on reaction conditions. The 1-isomer forms predominantly at 25 °C, and the 2-isomer at 160 °C.

Naphthalene can be hydrogenated under high pressure in the presence of metal catalysts to give 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene or tetralin (C

10H

12). Further hydrogenation yields decahydronaphthalene or decalin (C

10H

18). Oxidation with chromate or permanganate, or catalytic oxidation with O

2 and a vanadium catalyst, gives phthalic acid.

Production

Most naphthalene is derived from coal tar. From the 1960s until the 1990s, significant amounts of naphthalene were also produced from heavy petroleum fractions during petroleum refining, but today petroleum-derived naphthalene represents only a minor component of naphthalene production.

Naphthalene is the most abundant single component of coal tar. Although the composition of coal tar varies with the coal from which it is produced, typical coal tar is about 10% naphthalene by weight. In industrial practice, distillation of coal tar yields an oil containing about 50% naphthalene, along with a variety of other aromatic compounds. This oil, after being washed with aqueous sodium hydroxide to remove acidic components (chiefly various phenols), and with sulfuric acid to remove basic components, undergoes fractional distillation to isolate naphthalene. The crude naphthalene resulting from this process is about 95% naphthalene by weight. The chief impurities are the sulfur-containing aromatic compound benzothiophene (<2%), indane (0.2%), indene (<2%), and methylnaphthalene (<2%). Petroleum-derived naphthalene is usually purer than that derived from coal tar. Where required, crude naphthalene can be further purified by recrystallization from any of a variety of solvents, resulting in 99% naphthalene by weight, referred to as 80 °C (melting point). Approximately 1.3M tons are produced annually.[4]

In North America, coal tar producers are Koppers Inc. and Recochem Inc., and petroleum-derived producer is Advanced Aromatics, L.P. In Western Europe most known producers are Koppers, Ruetgers and Deza. In Eastern Europe, - variety of integrated metallurgy complexes (Severstal, Evraz, Mechel, MMK) in Russia. Dedicated naphthalene and phenol maker INKOR and Yenakievsky Metallurgy plant in Ukraine, and ArcelorMittal Temirtau in Kazakhstan.

Natural occurrence

Trace amounts of naphthalene are produced by magnolias and specific types of deer, as well as the Formosan subterranean termite, possibly produced by the termite as a repellant against "ants, poisonous fungi and nematode worms."[5] Some strains of the endophytic fungus Muscodor albus produce naphthalene among a range of volatile organic compounds, while Muscodor vitigenus produces naphthalene almost exclusively.[6]

Naphthalene has been found in meteorites. It has also been discovered in the interstellar medium in the direction of the star Cernis 52 in the constellation Perseus.[7]

Gaseous naphthalene

Protonated cations of naphthalene are the source of part of the spectrum of the unidentified interstellar bands (UIBs). The gaseous naphthalene found in space is different from the crystalline form typically used in mothballs in that it has an additional hydrogen atom, with the empirical formula: C

10H+

9. The UIBs have been observed by astronomers and there has been research directed at identifying the compounds responsible for them. This research has been publicized as "mothballs in space."[8]

Uses

As a chemical intermediate

Naphthalene is used mainly as a precursor to other chemicals. The single largest use of naphthalene is the industrial production of phthalic anhydride, although more phthalic anhydride is made from o-xylene. Other naphthalene-derived chemicals include alkyl naphthalene sulfonate surfactants, and the insecticide 1-naphthyl-N-methylcarbamate (carbaryl). Naphthalenes substituted with combinations of strongly electron-donating functional groups, such as alcohols and amines, and strongly electron-withdrawing groups, especially sulfonic acids, are intermediates in the preparation of many synthetic dyes. The hydrogenated naphthalenes tetrahydronaphthalene (tetralin) and decahydronaphthalene (decalin) are used as low-volatility solvents. Naphthalene is also used in the synthesis of 2-naphthol, a precursor for various dyestuffs, pigments, rubber processing chemicals and other miscellaneous chemicals and pharmaceuticals.[4]

Naphthalene sulfonic acids are used in the manufacture of naphthalene sulfonate polymer plasticizers (dispersants), which are used to produce concrete and plasterboard (wallboard or drywall). They are also used as dispersants in synthetic and natural rubbers, and as tanning agents (syntans) in leather industries, agricultural formulations (dispersants for pesticides), dyes and as a dispersant in lead–acid battery plates.

Naphthalene sulfonate polymers are produced by reacting naphthalene with sulfuric acid and then polymerizing with formaldehyde, followed by neutralization with sodium hydroxide or calcium hydroxide. These products are commercially sold in solution (water) or dry powder form.

- Sulfonation Step (sulfuric acid plus naphthalene):

- H

2SO

4 + C

10H

8 → C

10H

7-SO

3H + H

2O

- Polymerization Step (naphthalenesulfonic acid plus formaldehyde):

- C

10H

7-SO

3H + CH

2=O → SO

3H-C

10H

7-(-CH

2-C

10H

7-SO

3H)

n + H

2SO

4

- Neutralization Step (naphthalene sulfonic acid condensate plus sodium hydroxide):

- C

10H

7-SO

3H-(C

10H

7-SO

3H)

n + NaOH → C

10H

7-SO

3Na-(C

10H

7-SO

3Na)

n + H

2O + Na

2SO

4

Wetting agent and surfactant

Alkyl naphthalene sulfonates (ANS) are used in many industrial applications as nondetergent wetting agents that effectively disperse colloidal systems in aqueous media. The major commercial applications are in the agricultural chemical industry, which uses ANS for wettable powder and wettable granular (dry-flowable) formulations, and the textile and fabric industry, which utilizes the wetting and defoaming properties of ANS for bleaching and dyeing operations.

As a fumigant

Naphthalene has been used as a household fumigant. It was once the primary ingredient in mothballs, though its use has largely been replaced in favor of alternatives such as 1,4-dichlorobenzene. In a sealed container containing naphthalene pellets, naphthalene vapors build up to levels toxic to both the adult and larval forms of many moths that attack textiles. Other fumigant uses of naphthalene include use in soil as a fumigant pesticide, in attic spaces to repel animals and insects, and in museum storage-drawers and cupboards to protect the contents from attack by insect pests.

Naphthalene is a repellent to opossums and could be used to deter them from taking up residency in people's homes.[9][10]

Niche applications

It is used in pyrotechnic special effects such as the generation of black smoke and simulated explosions. In the past, naphthalene was administered orally to kill parasitic worms in livestock. Naphthalene and its alkyl homologs are the major constituents of creosote. Naphthalene is used in engineering to study heat transfer using mass sublimation.

Health effects

Exposure to large amounts of naphthalene may damage or destroy red blood cells. Humans, in particular children, have developed this condition, known as hemolytic anemia, after ingesting mothballs or deodorant blocks containing naphthalene. Symptoms include fatigue, lack of appetite, restlessness, and pale skin. Exposure to large amounts of naphthalene may cause confusion, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, blood in the urine, and jaundice (yellow coloration of the skin).[11] Over 400 million people have an inherited condition called glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Exposure to naphthalene is more harmful for these people and may cause hemolytic anemia at lower doses.[12]

When the US National Toxicology Program (NTP) exposed male and female rats and mice to naphthalene vapors on weekdays for two years,[13] male and female rats exhibited evidence of carcinogenic activity based on increased incidences of adenoma and neuroblastoma of the nose, female mice exhibited some evidence of carcinogenic activity based on increased incidences of alveolar and bronchiolar adenomas of the lung, and male mice exhibited no evidence of carcinogenic activity.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)[14] classifies naphthalene as possibly carcinogenic to humans and animals (Group 2B). The IARC also points out that acute exposure causes cataracts in humans, rats, rabbits, and mice; and that hemolytic anemia, described above, can occur in children and infants after oral or inhalation exposure or after maternal exposure during pregnancy. Under California's Proposition 65, naphthalene is listed as "known to the State to cause cancer".[15]

US government agencies have set occupational exposure limits to napthalene exposure. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set a permissible exposure limit at 10 ppm (50 mg/m3) over an eight hour time-weighted average. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has set a recommended exposure limit at 10 ppm (50mg/m3) over an eight hour time-weighted average, as well as a short-term exposure limit at 15 ppm (75 mg/m3).[16]

Research at the University of Colorado at Boulder revealed a probable mechanism for the carcinogenic effects of mothballs and some types of air fresheners containing naphthalene.[17][18]

Mothballs and other products containing naphthalene have been banned within the EU since 2008.[19][20]

In China, the use of naphthalene in mothballs is forbidden.[21] It is due partly to the health effects as well as the wide use of natural camphor as replacement. However naphthalene is widely produced for moth balls and currently exported from China.[22]

See also

- Decalin

- Camphor

- Mothballs

- Naphthol

- Classic naphthalene synthesis: the Wagner-Jauregg reaction

- Sodium naphthalenide

References

- ↑ Amoore J E and Hautala E (1983). "Odor as an aid to chemical safety: Odor thresholds compared with threshold limit values and volatiles for 214 industrial chemicals in air and water dilution". J Appl Toxicology 3 (6): 272–290. doi:10.1002/jat.2550030603.

- ↑ John Kidd (1821). "Observations on Naphthalene, a peculiar substance resembling a concrete essential oil, which is produced during the decomposition of coal tar, by exposure to a red heat". Philosophical Transactions 111: 209–221. doi:10.1098/rstl.1821.0017.

- ↑ Emil Erlenmeyer (1866). "Studien über die s. g. aromatischen Säuren". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie 137 (3): 327–359. doi:10.1002/jlac.18661370309.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gerd Collin, Hartmut Höke, Helmut Greim "Naphthalene and Hydronaphthalenes" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2003. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_001.pub2. Article Online Posting Date: March 15, 2003.

- ↑ "Termite 'mothball' keep insects at bay". Sci/Tech (BBC News). April 8, 1998.

- ↑ Daisy BH, Strobel GA, Castillo U, et al. (November 2002). "Naphthalene, an insect repellent, is produced by Muscodor vitigenus, a novel endophytic fungus". Microbiology (Reading, Engl.) 148 (Pt 11): 3737–41. PMID 12427963.

- ↑ "Interstellar Space Molecules That Help Form Basic Life Structures Identified". Science Daily. September 2008.

- ↑ "Mothballs in Space". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Summary of Possum Repellent Study".

- ↑ "Removing a possums from your roof", NSW Department of the Environment and Heritage, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/animals/RemovingAPossumFromYourRoof.htm

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Naphthalene poisoning

- ↑ Santucci K, Shah B. Association of naphthalene with acute hemolytic anemia. Acad Emerg Med. 2000 Jan;7(1):42–7.

- ↑ "NTP Technical Reports 410 and 500". NTP Technical Reports 410 and 500, available from NTP: Long-Term Abstracts & Reports. Retrieved March 6, 2005.

- ↑ "IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans". Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Some Traditional Herbal Medicines, Some Mycotoxins, Naphthalene and Styrene, Vol. 82 (2002) (p. 367). Retrieved December 25, 2008.

- ↑ Proposition 65, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

- ↑ CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- ↑ "Scientists May Have Solved Mystery Of Carcinogenic Mothballs", Physorg.com, June 20, 2006.

- ↑ "Mothballs, air fresheners and cancer". Environmental Health Association of Nova Scotia. Environmental Health Association of Nova Scotia. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ Alderson, Andrew (15 Nov 2008). "Holy straight bananas – now the Eurocrats are banning moth balls". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- ↑ Gray, Kerrina (17 November 2013). "Council warned against use of poisonous moth balls". Your Local Guardian (Newsquest (London) Ltd.). Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- ↑ 国务院经贸办、卫生部关于停止生产和销售萘丸提倡使用樟脑制品的通知(国经贸调(1993)64号)

- ↑ Search of Chinese online shop

- CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 87th edition

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naphthalene. |

- Mothballs Case Profile—National Pesticide Information Center

- Naphthalene—EPA Air Toxics Web Site

- Naphthalene (PIM 363)—mostly on toxicity of naphthalene

- Naphthalene—CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

| |||||||||||||||||