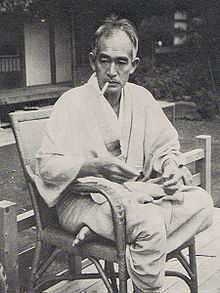

Naoya Shiga

| Naoya Shiga | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

20 February 1883 Ishinomaki, Miyagi, Japan |

| Died |

21 October 1971 (aged 88) Atami, Shizuoka, Japan |

| Occupation | writer |

| Genres | short story, novel |

| Literary movement | I Novel |

Naoya Shiga (志賀 直哉 Shiga Naoya, 20 February 1883 – 21 October 1971) was a Japanese novelist and short story writer active during the Taishō and Shōwa periods of Japan.

Early life

Shiga was born in Ishinomaki city, Miyagi prefecture. His father, the son of a samurai in the service of Sōma Domain, was a successful banker. The family moved to Tokyo when Shiga was three, to live with his grandparents, who were largely responsible for raising him. Shiga's mother died when he was thirteen and his father remarried not long after. Shiga’s relationship with his father became increasingly strained after the former was converted to Christianity by Uchimura Kanzō[citation needed], began advocating social causes and attempted to participate in protests in 1901 over the Ashio Copper Mine, which polluted an adjacent river and poisoned local inhabitants. Shiga’s father, whose bank was part owner of the mine, managed to forbid his participation in the protest, but another crisis arose when Shiga declared his intention to marry one of the family’s maids, with whom he was having an affair. The maid was removed from the household, and Shiga was severely criticized for what his father felt was an irresponsible and aimless lifestyle. Shiga graduated from the Gakushuin Peer's Elementary School and attended Tokyo Imperial University from 1906. However, he was a mediocre student and left university in 1910 without graduating.

Literary career

While Shiga was at the Gakushuin he became friends with Saneatsu Mushanokōji and Kinoshita Rigen. His literary career began with a handwritten literary magazine Boya ("Perspective"), which was circulated within their literary group at the school. In 1910 Shiga contributed the story Abashiri made ("To Abashiri") to the first issue of the literary magazine Shirakaba, which he helped to create. To the dismay of his family, Shiga announced his intention to become a professional writer. In 1912, he published Otsu Junkichi, a thinly-veiled autobiography of his affair with the family maid. The family was so scandalized by the novella that Shiga was forced to move out of the family home. The work was also a forerunner of Shiga’s adherence to the indigenous I Novel literary form, which uses the author's subjective recollection of his own experiences. During this period, Shiga established his reputation as a writer of short stories, including Kamisori ("The Razor", 1910), Seibei to hyotan ("Seibei’s Gourd", 1913) and Manazuru (1920). After Shiga married the cousin of Saneatsu Mushanokōji, who was a widow already with a child, in 1914, the break in relations with his father became complete, and he renounced his inheritance. However, after the birth of his second daughter in 1917, he was reconciled with his father, and related the story in his novel Wakai ("Reconciliation", 1917). This was followed by his major work, An'ya Koro (A Dark Night's Passing, 1921–1937), which was serialized in the socialist magazine Kaizō.

Shiga's terse style influenced many later writers, and was praised by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa and Agawa Hiroyuki. However, other contemporaries, notably Dazai Osamu, were strongly critical of this "sincere" style.

During his lifetime Shiga moved house an estimated 28 times in various locations around Japan. He wrote stories connected with most of the places he lived in, including Kinosaki ni te ("At Cape Kinosaki") and Sasaki no bai ("In the case of Sasaki"). One of his longer stays was in Nara, where he lived in a house facing Nara Park from 1925-1938. Due to frequent visitors from the literary world, the house was dubbed the "Takabatake Salon" from the name of its neighborhood. The house has been preserved, and is open to the public as a memorial museum. After Nara, Shiga moved to Kamakura, and from there he moved to the hot spring resort town of Atami, Shizuoka from the war years onwards. Frequent visitors to his house included the writer Hirotsu Kazuo and the film director Yasujirō Ozu.

Later life

Shiga was awarded the Order of Culture by the Japanese government in 1949.

Shiga suffered the fate of many authors who are successful in their early years, combined with the fatal weakness of authors specializing in the autobiographical novel – after a while there is little or nothing left to write about. During the last 35 years of his life he occasionally appeared as a guest writer in various literary journals, where he reminisced about his early association with various Shirakaba school writers, or his former interest in Christianity, but he produced very little new work. He died of pneumonia, after a long illness, at the age of 88. His grave is at the Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo.

See also

- Japanese literature

- List of Japanese authors

Translations

- McClellan, Edwin, A Dark Night's Passing, Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd, 1976. ISBN 0-87011-279-1

- Dunlop, Lane, The Paper Door and Other Stories by Shiga Naoya, San Francisco: North Point, 1987. ISBN 0-86547-419-2

References

- Agawa, Hiroyuki. Shiga Naoya. Iwanami Shoten (1994). ISBN 4-00-002940-1

- Kohl, Stephen William. Shiga Naoya: A Critical Biography. UMI Dissertation Services (1974). ASIN: B000C8QIWE

- Starrs, Roy An Artless Art - The Zen Aesthetic of Shiga Naoya: A Critical Study with Selected Translations. RoutledgeCurzon (1998). ISBN 1-873410-64-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naoya Shiga. |

- Shiga Naoya's former residence in Nara

- National Diet Library biography

- Prominent people of Minato City

- Shiga Naoya’s former residence in Onomichi

- J'Lit | Authors : Naoya Shiga | Books from Japan (English)

|