Néstor Kirchner

| Néstor Kirchner | |

|---|---|

| |

| president Néstor Kirchner in March 2007 | |

| 51st President of Argentina | |

| In office 25 May 2003 – 10 December 2007 | |

| Vice President | Daniel Scioli |

| Preceded by | Eduardo Duhalde |

| Succeeded by | Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

| Secretary General of the Union of South American Nations | |

| In office 4 May 2010 – 27 October 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | María Emma Mejía Vélez |

| Deputy of Argentina For Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office 3 December 2009 – 27 October 2010 | |

| Governor of Santa Cruz | |

| In office 10 December 1991 – 25 May 2003 | |

| Vice Governor | Eduardo Arnold (1991–1999) Héctor Icazuriaga (1999–2003) |

| Preceded by | Ricardo del Val |

| Succeeded by | Héctor Icazuriaga |

| Mayor of Río Gallegos | |

| In office 1987–1991 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Néstor Carlos Kirchner 25 February 1950 Río Gallegos, Santa Cruz, Argentina |

| Died | 27 October 2010 (aged 60) El Calafate, Santa Cruz, Argentina |

| Resting place | Río Gallegos |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party | Justicialist Party |

| Other political affiliations |

Front for Victory (2003-present) |

| Spouse(s) | Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (1975–2010) |

| Children | Máximo Kirchner Florencia Kirchner |

| Alma mater | National University of La Plata |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |  |

Néstor Carlos Kirchner (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈnestoɾ ˈkaɾlos ˈkiɾʃneɾ ˈostoitʃ]; 25 February 1950 – 27 October 2010) was an Argentine politician who served as President of Argentina from 25 May 2003 until 10 December 2007. Previously, he was Governor of Santa Cruz Province since 10 December 1991. He briefly served as Secretary General of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and as a National Deputy of Argentina for Buenos Aires Province. Kirchner's four-year presidency was notable for presiding over a dramatic fall in poverty and unemployment, following the economic crisis of 2001,[1][2] together with an extension of social security coverage, a major expansion in housing and infrastructure, higher spending on scientific research and education, and substantial increases in real wage levels.[3]

A Justicialist, Kirchner was little-known internationally and even domestically before his election to the Presidency, which he won by default with only 22.2 percent of the vote in the first round, when former president Carlos Menem (24.4%) withdrew from the ballotage. Soon after taking office in May 2003, Kirchner surprised some Argentinians by standing down powerful military and police officials. Stressing the need to increase accountability and transparency in government, Kirchner overturned amnesty laws for military officers accused of torture and assassinations during the 1976–1983 "Dirty War" under military rule.[4]

On 28 October 2007, his wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was elected to succeed him as President of Argentina. Thus, Kirchner then became the First Gentleman of Argentina. In 2009, he was elected a National Deputy for Buenos Aires Province. He was also appointed Secretary General of the Union of South American Nations on 4 May 2010.[5]

Kirchner, who had been operated on twice in 2010 for cardiovascular problems, died at his home in El Calafate, Santa Cruz Province, on 27 October 2010, after reportedly suffering a heart attack.[6] For more than 24 hours, hundreds of thousands of people filed past Kirchner's body lying in state,[7] in a state funeral at the Casa Rosada attended by several Argentine personalities and eight South American leaders.[8] On the afternoon of 29 October, a funeral procession accompanied Kirchner's body from Casa Rosada to the metropolitan airport[9] and then from the airport of Río Gallegos to the cemetery where he was buried.[9]

Early life

Kirchner was born in Río Gallegos, in the Patagonian province of Santa Cruz.[10] His mother, María Juana Ostoić Dragnić, is Chilean of Croatian descent and his father, also named Néstor, a post office official, was of Swiss-German descent. He received his primary and secondary education at local public schools, and his high-school diploma from the Argentine school Colegio Nacional República de Guatemala.

He was part of the third generation of the family living in Río Gallegos.

He moved to La Plata to study law in 1969 at the National University there, joining the political student unions of peronist ideology. He promoted the return of Juan Domingo Perón to the country and was present at the Ezeiza massacre.[11] He graduated as juris doctor in 1976. That year he met Cristina Fernández, marrying her six months later.

Kirchner returned immediately with his wife to Río Gallegos, to escape from the Dirty War and the 1976 Argentine coup d'état.[12] He established a law firm with the lawyer Domingo Ortiz de Zarate. Cristina Fernández joined the firm in 1979, when she got her own law degree.[13] The firm worked for banks and financial groups that filled eviction lawsuits, as the 1050 ruling of the Central Bank had increased the price of the mortgage loan's interests.[13] They also defended the police officer Gomez Ruoco, accused of violation of human rights during the Dirty War.[13]

After the downfall of the military dictatorship and restoration of democracy in 1983, Kirchner became a public officer in the provincial government. The following year, he was briefly president of the Río Gallegos social welfare fund, but was forced out by the governor because of a dispute over financial policy. The affair made him a local celebrity and laid the foundation for his career.[14]

By 1986, Kirchner had developed sufficient political capital to be put forward as the PJ's candidate for mayor of Río Gallegos. He won the 1987 elections for this post by a slim margin of about 100 votes. Fellow PJ member Ricardo del Val became governor, keeping Santa Cruz firmly within the hands of the PJ.[citation needed] Kirchner's performance as mayor from 1987 to 1991 was satisfactory enough to the electorate and to the party to enable him to run for governor in 1991, where he won with 61% of the vote. By this time his wife was also a member of the provincial congress.[citation needed]

Governor of Santa Cruz

When Kirchner assumed the governorship, the province of Santa Cruz was being battered by the then ongoing economic crisis, with high unemployment and a budget deficit equal to US$1.2 billion.[15]

In 1994 and 1998, Kirchner introduced amendments to the provincial constitution, to enable him to run for re-election indefinitely. As a member of the 1994 Constitutional Assembly organized by Menem and former president Raúl Alfonsín, Kirchner participated in the drafting of a new national constitution which allowed the president to be re-elected for a second four-year term.

In 1995, with his constitutional changes in place, Kirchner was easily re-elected to a second term as governor, with 66.5% of the votes. But by now, Kirchner was distancing himself from the charismatic and controversial Menem, who was also the nominal head of the PJ; this was made particularly apparent with the launch of Corriente Peronista, an initiative supported by Kirchner to create an alternative space within the Justicialist Party, outside of Menem's influence.[16]

Although Menem was not allowed by the Constitution to run for a third term, he attempted to do so with an ad-hoc interpretation of it. This project was resisted by most other politicians of the PJ, who even threatened to impeach any judge that allowed such interpretation. Public polls were against a third presidency of Menem as well. The most influential politician opposing Menem was Eduardo Duhalde, governor of the populous Buenos Aires Province. No other major politician of the PJ opposed the candidacy of Duhalde, who run for the 1999 presidential election without primary elections. Still, Menem made many controversial actions, in order to undermine the chances of Duhalde in the election.[17] Néstor Kirchner was aligned with Duhalde during this dispute.

Menem did not run, and the PJ nominated Duhalde, who was in turn defeated during the October 1999 elections by Buenos Aires Mayor Fernando de la Rúa, the Alliance candidate, and the party lost its majority in Congress. Although the Alianza also made headway in Santa Cruz, Kirchner managed to be re-elected to a third term as governor in May 1999 with 45.7% of the vote. De la Rúa's victory was in part a rejection of Menem's perceived flamboyance and corruption during his last term. De la Rúa instituted austerity measures and reforms to improve the economy; taxes were increased to reduce the deficit, the government bureaucracy was trimmed, and legal restrictions on union negotiations were eased.

These moves did not prevent a deepening of the Argentine economic crisis, however, and a crisis of confidence ensued by November 2001, as domestic depositors began a run on the banks, resulting in the highly unpopular corralito, a limit, and subsequently a full ban, on withdrawals. These developments led to the December 2001 riots, and to president de la Rúa's resignation on 21 December.

A series of interim presidents and renewed demonstrations ended with the appointment of Eduardo Duhalde as interim president in January 2002. Duhalde abolished the fixed exchange rate regime that had been in place since 1991, and the Argentine peso quickly devalued by more than two thirds of its value, diminishing middle-class savings and sinking the heavily import-dependent Argentine economy even deeper, but giving a significant profit boost to Argentinian exports. Amid strong public rejection of the entire political class, characterized by the pithy slogan que se vayan todos ("away with them all"), Duhalde brought elections forward by six months.

2003 presidential election

Carlos Menem originally ran for a new term as president, and Eduardo Duhalde tried to prevent it. Instead of holding primary elections within the PJ, all the Peronist candidates were allowed to run in the main election, using political parties created for the event. Even though Kirchner ran for the presidency with the support of Eduardo Duhalde, he was not the initial candidate chosen by the president. Trying to prevent a third term of Carlos Menem, he sought to promote a candidate that may defeat him, but Carlos Reutemann (governor of Santa Fe) did not accept and José Manuel de la Sota (governor of Córdoba) did not grow in the polls. He also tried with Mauricio Macri, Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, Felipe Solá and Roberto Lavagna, to no avail. He initially resisted helping Kirchner, fearing that he may ignore Duhalde once in the presidency.[18] As Kirchner was identified with the centre-left, Duhalde boosted his image by appointing Daniel Scioli as his vice-presidential candidate, who was identified with the centre-right.[19]

The general election took place on April 27. Carlos Menem won the election by 24,5%, followed by Néstor Kirchner with 22,2%. This result triggered a runoff election, which was canceled when Menem withdrew. Menem had a negative image, and pre-electoral polls forecasted a victory of Kirchner by more than 60%. The judiciary declined requests to call a new election or to hold a runoff election between Kirchner and Ricardo López Murphy (the third most-voted candidate, who refused to run in the runoff as well). The election was validated by the Congress, and Kirchner became president on May 25, 2003. He is the Argentine president elected with the lowest percentage of the vote.[20]

Presidency

First days

Kirchner came into office on the tail of a deep economic crisis. A country which had once equalled Europe in levels of prosperity and considered itself a bulwark of European culture in South America found itself deeply impoverished, with a depleted middle class and malnutrition appearing in the lower strata of society. The country was burdened with $178 billion in debt, the government strapped for cash. While associated to the clientelist and nearly feudal style of government of many provincial governors and the corruption of the PJ, Kirchner was comparatively unknown to the national public, and he showed himself as a newcomer who had arrived at the Casa Rosada without the usual whiff of scandal about him, trying not to make a point of the fact that he himself had seven times been on the same electoral ballot with Menem.

Supreme Court changes

Shortly after coming into office, Kirchner made changes to the Argentine Supreme Court. He accused certain justices of extortion and pressured them to resign, while also fostering the impeachment of two others. In place of a majority of politically right-wing and religiously conservative justices, he appointed new ones who were ideologically closer to him, including two women (one of them an avowed atheist). Kirchner also retired dozens of generals, admirals, and brigadiers from the armed forces, a few of them with reputations tainted by the atrocities of the Dirty War.[21][22]

Economic policy

Kirchner kept the Duhalde administration's Minister of the Economy, Roberto Lavagna. Lavagna also declared that his first priority now was social problems. Argentina's default was the largest in financial history, and ironically it gave Kirchner and Lavagna significant bargaining power with the IMF, which loathes having bad debts on its books. During his first year of office, Kirchner achieved a difficult agreement to reschedule $84 billion in debts with international organizations, for three years. In the first half of 2005, the government launched a bond exchange to restructure approximately $81 billion of national public debt (an additional $20 billion in past defaulted interest was not recognized). Over 76% of the debt was tendered and restructured for a recovery value of approximately one-third of its nominal value.[14]

On 15 December 2005, following Brazil's initiative, Kirchner announced the cancellation of Argentina's debt to the IMF in full and offered a single payment, in a historic decision that generated controversy at the time (see Argentine debt restructuring). Some commentators, such as Mark Weisbrot of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, suggest that the Argentine experiment has thus far proven successful.[23] Others, such as Michael Mussa, formerly on the staff of the International Monetary Fund and now with the Peterson Institute, question the longer-term sustainability of Pres. Kirchner's approach.[24]

In a meeting with executives of multinational corporations on Wall Street—after which he was the first Argentine president to ring the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange—Kirchner defended his "heterodox economic policy, within the canon of classic economics" and criticized the IMF for its lack of collaboration with the Argentine recovery.[25]

Foreign policy

Néstor Kirchner took a pragmatic approach towards the Argentine foreign policy.[26] The Argentina–United States relations did not continue the automatic alignment held in the 1990s, but did not become anti-americanist either. Kirchner opposed the Free Trade Area of the Americas. Kirchner mentioned in the UN that, although he firmly opposes terrorism, he did not support the War on Terror.[27]

Kirchner sought an increased integration with other Latin American countries. He relaunched the Mercosur, sought to add new countries to it, and improved the relations with Brazil.[14][28] Still, Argentina did not automatically align with Brazil, the regional power of South America.[29]

2005 midterm elections

Kirchner saw the 2005 parliamentary elections as a means to confirm his political power, since Carlos Menem's defection in the second round of the 2003 presidential elections had not allowed Kirchner to receive the large number of votes that surveys predicted. Kirchner explicitly stated that the 2005 elections would be like a mid-term plebiscite for his administration, and he actively participated in the campaign in most provinces. Due to internal disagreements, the Justicialist Party was not presented as such on the polls but split into several factions. Kirchner's Frente para la Victoria (FPV, Front for Victory) was overwhelmingly the winner (the candidates of the FPV got more than 40% of the national vote), following which many supporters of other factions (mostly those led by former presidents Eduardo Duhalde and Carlos Menem) migrated to the FPV.

On 2 July 2007, Kirchner announced he would not seek re-election in the October elections, despite having the support of 60% of those surveyed in polls.

Kirchner secured the Presidency of the Justicialist Party (to which his FPV belongs), in April 2008.[30] Following the FPV's loss of 4 Senators and over 20 Congressmen in the 28 June 2009 mid-term elections, however, he was replaced by Buenos Aires Province Governor Daniel Scioli.[31]

Post-presidency

Kirchner remained a highly influential politician during the term of his successor and wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. The press developed the term "presidential marriage" to make reference to both of them at once.[32] Some political analysts compared this type of government with a diarchy.[33] He took part in the Operation Emmanuel in Colombia to release a group of FARC hostages, in December 2007.[34] The Colombian politician Íngrid Betancourt was among the group of hostages. Kirchner returned to Argentina after the failure of the negotiations;[35] the hostages were released a year later by a covert operation by Colombian military forces known as "Operacion Jaque" as a result of the reluctance of the guerilla to release the hostages, including Ingrid Betancourt and three Americans.

Néstor Kirchner took active part in the government conflict with the agricultural sector in 2008. During this conflict he became president of the Justicialist Party, and declared full support for Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in the conflict.[36] He accused the agricultural sector of attempting a coup d'état.[37] He was one of the speakers in a demonstration made next to the Argentine National Congress supporting a law project on the matter, that would be voted the following day. Kirchner requested by then to accept the result in the Congress.[38] Many senators who had formerly supported the government's proposal rejected it. The voting ended in a tie with 36 supporting votes and 36 rejecting votes. As a result, vicepresident Julio Cobos, president of the chamber of senators, was required to cast a decisive vote. Cobos voted for the rejection, and the law proposal was rejected.[39]

On June 2009 legislative elections he ran for National Deputy for the Buenos Aires Province district. He was elected along with other 11 Front for Victory candidates, as their ticket arrived close second to the Union PRO peronist-conservative coalition in that district.[40][41]

Néstor Kirchner was proposed by Ecuador as a candidate Secretary General of Unasur, but was rejected by Uruguay, at a time when Uruguay and Argentina were debating the Pulp mill dispute. The dispute was resolved in 2010 and the new Uruguayan president, José Mujica, supported Kirchner's candidacy. Kirchner was unanimously elected the first Secretary General of Unasur, during a Unasur Member States Heads of State summit held in Buenos Aires on 4 May 2010.[42] In that role, he successfully mediated in the 2010 Colombia–Venezuela diplomatic crisis.[43][44]

Personal style and ideology

Néstor Kirchner is considered at times as a left-wing president,[45] but that consideration is relative.[46] Although Kirchner was to the left of previous Argentine presidents, from Raúl Alfonsín to Eduardo Duhalde, and contemporary Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, he was to the right of other Latin American presidents such as Hugo Chávez or Fidel Castro.[46] His strong nationalist approach to the Falkland Islands sovereignty dispute was closer to right-wing politics,[47] and he did not consider classic left-wing policies such as socialization of production or the nationalization of the public services privatized during the presidency of Carlos Menem.[47] He did not attempt either to modify the institutional system, the church–state relations or disestablish the armed forces.[47] His view of the economy was influenced by his government of Santa Cruz, a province rich in oil, gas, fish and tourism and strongly focused on the primary sector of the economy.[29]

Néstor Kirchner was a Peronist, and managed the political power as the historical Peronist leaders have traditionally done.[48] One of the characteristics of his political style was the constant generation of controversies with other political or social forces, and the polarization of public opinion.[49] This strategy was used against financial sectors, military, police, foreign countries, international bodies, newspapers, and even Duhalde himself, with varying levels of success.[50] Kirchner sought to generate an image contrasting that of former presidents Carlos Menem and Fernando de la Rúa. Menem was seen as frivolous, and De la Rúa as doubtful, so Kirchner worked to be seen as serious and determined.[51]

Kirchner was a critic of IMF structural adjustment programs. His criticisms were supported in part by former World Bank economist Joseph Stiglitz, who opposes the IMF's measures as recessionary and urged Argentina to take an independent path. According to some commentators, Kirchner was seen as part of a spectrum of new South American leaders, including Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil and Tabaré Vázquez in Uruguay, who see the Washington consensus as an unsuccessful model for economic development in the region.

Kirchner's increasing alignment with Hugo Chávez became evident when during a visit to Venezuela on July 2006 he attended a military parade alongside Bolivian president Evo Morales. On that occasion Mr. Chávez called for a defensive military pact between the armies of the region with a common doctrine and organization. Kirchner stated in a speech to the Venezuela national assembly that Venezuela represented a true democracy fighting for the dignity of its people.[52]

Kirchner emphasised holding businesses accountable to Argentine institutions, laws prompting environmental standards, and contractual obligations. He pledged to not open his administration to the influence of interests that "benefited from inadmissible privileges in the last decade" during Carlos Menem's presidency. These groups, according to Kirchner, were privileged by an economic model that favored "financial speculation and political subordination" of politicians to well-connected elites.[53] For instance, in 2006, citing the alleged failure of Aguas Argentinas, a company partly owned by the French utility group Suez, to meet its contractual obligation to improve the quality of water, Kirchner terminated the company's contract with Argentina to provide drinking water to Buenos Aires.[54]

His preference for a more active role of the state in the economy was underscored with the founding, in 2004, of ENARSA a new state owned energy company. At the June 2007 Mercosur summit, he scolded energy companies for their lack of investment in the sector and for not supporting his strategic vision for the region. He said he was losing patience with energy companies as South America's second-largest economy faced power rationing and shortages during the Southern Hemisphere winter. Price controls on energy rates instituted in 2002 are attributed to have limited investment in Argentina's energy infrastructure, risking more than four years of economic growth greater than 8 percent.[55][56]

Kirchner's collaborators and others who supported him and were politically close to him were known informally as pingüinos ("penguins"), alluding to his birthplace in the cold southern region of Argentina.[57][58] Some media and sectors of society also resorted to using the letter K as a shorthand for Kirchner and his policies (as seen, for example, in the controversial group of supporters self-styled Los Jóvenes K,[59] that is "The K Youth", and in the faction of the Radical Civic Union that supports Kirchner, referred to by the media as Radicales K).[60]

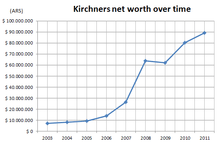

Allegations of embezzlement

Official reports from Argentina's anti-corruption office show that the fortune of the Argentine presidential couple, president Cristina Kirchner and her immediate predecessor and husband, Néstor Kirchner jumped from $7,000,000 to $82,000,000 from 2003 to 2012. Their net worth soared nearly 1172% since they first took office in 2003.[61]

The couple and several of their closest aides have been accused of purchasing from the Santa Cruz province government (their political turf) land at rock bottom farm prices which rapidly were converted into urban and suburban districts in exclusive resort areas valued in millions of dollars.[62]

Opponents of Kirchner claim that US$600m of assets belonging to Santa Cruz were not fully accounted for. The provincial government says the money was invested in public works.[63]

Death

Néstor Kirchner died of heart failure on 27 October 2010.[64] He had been expected to run for president in 2011.[65]

A wake was held from 28 October at the Casa Rosada presidential palace in Buenos Aires with the attendance of Latin American leaders.[8] For more than 24 hours, hundreds of thousands of people filed past Kirchner's body lying in state,[7] at the Casa Rosada. Starting on the afternoon of 29 October a large procession accompanied the remains of Néstor Kirchner from Casa Rosada to the metropolitan airport,[9] and another from the airport of Río Gallegos to the cemetery.[9] Cristina Fernández de Kirchner presided over the funeral, making her first public appearance since Néstor's death.[66]

Argentina declared three days of national mourning.[67] Condolences came from the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon,[68] the European Union,[68] the OAS,[69] The Union of South American Nations declared three days of national mourning in all South American countries.[70][71] Eight South American heads of state traveled to Buenos Aires for the funeral[72] and many others offered condolences.

Bibliography

- Alberto Amato (28 October 2010). "1950–2010 / Néstor Kirchner, ex presidente de la Nación". In Facundo Landívar. Clarín (in Spanish) (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Special edition (23.293). ISSN 1514-965X.

- Epstein, Edward (2006). Broken promises? The Argentine crisis and Argentine democracy. United Kingdom: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0928-1. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- Fraga, Rosendo (2010). Fin de ciKlo: ascenso, apogeo y declinación del poder kirchnerista (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Ediciones B. ISBN 978-987-627-167-7.

- Hedges, Jill (2011). Argentina: A modern history. United States: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-654-7. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- Mendelevich, Pablo (2010). El Final (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Ediciones B. ISBN 978-987-627-166-0.

References

- ↑ "Elections in Argentina: Cristina's Low-Income Voter Support Base". Upsidedownworld.org. 24 October 2007.

- ↑ "Latin American Program". Wilson Center.

- ↑ http://www.columbia.edu/~mm2140/Publications%20in%20English_files/JOD08.pdf

- ↑ Human Rights Watch. January 2004. Overview of human rights issues in Argentina.

- ↑ "Nestor Kirchner to Head South American Bloc" The New York Times

- ↑ Consternación por la muerte del ex presidente Néstor Kirchner (Spanish)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Masiva despedida al ex presidente Néstor Kirchner". lanacion.com. 29 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Restos de Néstor Kirchner serán velados en la Casa Rosada". Telesurtv. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "La larga despedida unió la Capital con el Sur". lanacion.com. 29 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ↑ "Argentine ex-leader Kirchner dies". Al-Jazeera. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ↑ Amato, p.4-5

- ↑ Amato, p. 5

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Mariela Arias (September 28, 2012). "Cómo fueron los "exitosos años" de Cristina Kirchner como abogada en Santa Cruz" [How were the "successful years" of Cristina Kirchner in Santa Cruz] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Council on Hemispheric Affairs, 27 January 2006. Argentina's Néstor Kirchner: Peronism Without the Tears

- ↑ Epstein, p. 13

- ↑ La Nación, 28 April 2003. "El patagónico que pegó el gran salto".

- ↑ Hedges, pp. 267-268

- ↑ Fraga, p. 19-20

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 21-23

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 27-31

- ↑ Washington Times. 22 July 2003. Argentine leader defies pessimism.

- ↑ BBC News. 25 May 2004. Argentine revival marks Kirchner first year.

- ↑ Weisbrot, Mark, "Doing it their own way", International Herald Tribune, 28 December 2006

- ↑ "Global Economic Prospects 2006/2007" (PDF). Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ La Nación, 21 September 2006. "El Presidente tuvo 45 minutos para convencer a los inversores"

- ↑ Fraga, p. 36

- ↑ "Argentina's Kirchner Calls at UN for "New Financial Architecture"" (in Spanish). Executive Intelligence Review. September 29, 2006. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ↑ Worldpress.org. September 2003. "Kirchner Reorients Foreign Policy". Translated from article in La Nación, 15 June 2006.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Fraga, p. 37

- ↑ "La Justicia confirmó a Néstor Kirchner como presidente del Partido Justicialista" (in Spanish). Infobae. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Scioli estrenó su liderazgo peronista". Clarín (in Spanish). 30 June 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ Mendelevich, p. 279

- ↑ Mendelevich, p. 280

- ↑ Sarkozy le pidió "ayuda" a Kirchner en el conflicto con las FARC (Spanish)

- ↑ Tras fracasar el rescate de los tres rehenes, volvió Kirchner (Spanish)

- ↑ Contraataque de Kirchner: sumará al PJ a la pelea (Spanish)

- ↑ El PJ acusó al campo de agorero y golpista y respaldó a Cristina (Spanish)

- ↑ Kirchner reforzó los ataques al campo en su última apuesta antes del debate (Spanish)

- ↑ Argentine Senate rejects farm tax, BBC News, 17 July 2008.

- ↑ "República Argentina". Elecciones. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Clarín, 2009 Legislative Election Results, published 28 June 2009". Clarin. 28 June 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Kirchner to head Americas bloc". Al Jazeera. 5 May 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ "Kirchner: "We Latin Americans have proved we can solve our own problems"". english.telam.com.ar. 11 August 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ "Hillary Clinton praises Argentina's role in Venezuela-Colombia conflict". /www.buenosairesherald.com. 12 August 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ BBC News. 18 April 2006. Analysis: Latin America's new left axis.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Fraga, p. 33

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Fraga, p. 34

- ↑ Fraga, p. 38

- ↑ Fraga, p. 40

- ↑ Fraga, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Fraga, p. 52

- ↑ (Spanish) La Nación. 5 July 2006. "Kirchner dejó un fuerte apoyo a Chávez y se llevó un gesto por Malvinas".

- ↑ "The Argentine Presidential Election: Is Political Renewal Possible?". Americas IRC Online. 5 June 2003. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "Argentina severs Suez water deal". BBC. 21 March 2006. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ (Spanish) La Nación 30 June 2007. "Duras críticas a empresas energéticas"

- ↑ Bloomberg 29 June 2007 "Argentina's Kirchner Says Patience Is Wearing Thin"

- ↑ Buenos Aires Herald. "March of the Penguins"

- ↑ (Spanish) Clarín. 18 January 2006. "Un combate entre "pingüinos" por la estratégica secretaría de Agricultura"

- ↑ (Spanish) Jóvenes K — Official website.

- ↑ (Spanish) Clarín. 12 August 2006. "Los radicales K respaldaron las políticas del gobierno y se distancian de la UCR"

- ↑ Maia Jastreblansky (December 11, 2012). "El crecimiento de los bienes de los Kirchner: de 7 a 89 millones de pesos" [The net worth growth of the Kirchner: from 7 to 89 millions of pesos] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ↑ Lucio Fernández Moores. "Hoteles, mansiones y lotes de los Kirchner y sus amigos en El Calafate". Clarín.

- ↑ "Argentina under the Kirchners: Socialism for foes, capitalism for friends". The Economist. 25 February 2010. Retrieved 2012-02-23.

- ↑ "Murió el ex presidente Néstor Kirchner" [Former president Néstor Kirchner has died]. Clarín (in Spanish). Buenos Aires. 27 October 2010.

- ↑ "Argentine ex-leader Kirchner dies". Al Jazeera. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "Argentine president presides over Kirchner's funeral". Xinhua. 29 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ↑ "Tres días de duelo". Pagina12. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Líderes de todo el mundo lamentan el fallecimiento de Kirchner". El País. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "El recuerdo de Sudamérica y del mundo". página12.com.ar. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "Unasur declaró tres días duelo sudamericano por la muerte de Kirchner". ambitoweb.com. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ↑ "Unasur: Kirchner "fue un convencido de la unidad de los pueblos latinoamericanos", Telesur". Telesurtv.net. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "Elocuente apoyo de los presidentes latinoamericanos". Lanacion.com.ar. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Néstor Kirchner. |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Néstor Kirchner |

- Official website for the 2011 presidential campaign

- (Spanish) Biography by CIDOB Foundation

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by position created |

Secretary General of Unasur 2010 |

Succeeded by María Emma Mejía Vélez |

| Preceded by Eduardo Duhalde |

President of Argentina 2003–2007 |

Succeeded by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

| Preceded by Héctor Marcelino García |

Governor of Santa Cruz 1991–2003 |

Succeeded by Héctor Icazuriaga |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

First Gentleman of Argentina 2007–2010 |

Succeeded by Vacant |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|