Mycobacterium tuberculosis sRNA

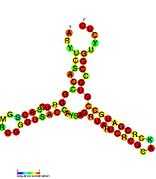

Mycobactierum tuberculosis contains at least nine small RNA families in its genome.[1] The small RNA (sRNA) families were identified through RNomics - the direct analysis of RNA molecules isolated from cultures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[2][3] The sRNAs were characterised through RACE mapping and Northern blot experiments.[1] Secondary structures of the sRNAs were predicted using Mfold.[4]

sRNAPredict2 - a bioinformatics tool - suggested 56 putative sRNAs in M. tuberculosis, though these have yet to be verified experimentally.[5] Hfq protein homologues have yet to be found in M. tuberculosis;[6] an alternative pathway - potentially involving conserved C-rich motifs - has been theorised to enable trans-acting sRNA functionality.[1]

sRNAs were shown to have important physiological roles in M. tuberculosis. Overexpression of G2 sRNA, for example, prevented growth of M. tuberculosis and greatly reduced the growth of M. smegmatis; ASdes sRNA is thought to be a cis-acting regulator of a fatty acid desaturase (desA2) while ASpks is found with the open reading frame for Polyketide synthase-12 (pks12) and is an antisense regulator of pks12 mRNA.[1]

The sRNA ncrMT1302 was found to be flanked by the MT1302 and MT1303 open reading frames. MT1302 encodes an adenylyl cyclase that converts ATP to cAMP, the expression of ncrMT1302 is regulated by cAMP and pH.[7]

See also

- Bacterial small RNA

- Caenorhabditis elegans sRNA

- Bacillus subtilis sRNAs

- Escherichia coli sRNA

- Pseudomonaa sRNA

| ||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Arnvig KB, Young DB (August 2009). "Identification of small RNAs in Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Mol. Microbiol. 73 (3): 397–408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06777.x. PMC 2764107. PMID 19555452. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Vogel J, Bartels V, Tang TH, et al. (November 2003). "RNomics in Escherichia coli detects new sRNA species and indicates parallel transcriptional output in bacteria". Nucleic Acids Res. 31 (22): 6435–43. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg867. PMC 275561. PMID 14602901. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Kawano M, Reynolds AA, Miranda-Rios J, Storz G (2005). "Detection of 5′- and 3′-UTR-derived small RNAs and cis-encoded antisense RNAs in Escherichia coli". Nucleic Acids Res. 33 (3): 1040–50. doi:10.1093/nar/gki256. PMC 549416. PMID 15718303. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Zuker M (July 2003). "Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction". Nucleic Acids Res. 31 (13): 3406–15. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg595. PMC 169194. PMID 12824337. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Livny J, Brencic A, Lory S, Waldor MK (2006). "Identification of 17 Pseudomonas aeruginosa sRNAs and prediction of sRNA-encoding genes in 10 diverse pathogens using the bioinformatic tool sRNAPredict2". Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (12): 3484–93. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl453. PMC 1524904. PMID 16870723. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Sun X, Zhulin I, Wartell RM (September 2002). "Predicted structure and phyletic distribution of the RNA-binding protein Hfq". Nucleic Acids Res. 30 (17): 3662–71. doi:10.1093/nar/gkf508. PMC 137430. PMID 12202750. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- ↑ Pelly S, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G (2012). "A screen for non-coding RNA in Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals a cAMP-responsive RNA that is expressed during infection.". Gene 500 (1): 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2012.03.044. PMC 3340464. PMID 22446041.

Further reading

- Pánek J, Bobek J, Mikulík K, Basler M, Vohradský J (2008). "Biocomputational prediction of small non-coding RNAs in Streptomyces". BMC Genomics 9: 217. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-217. PMC 2422843. PMID 18477385. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- Livny J, Waldor MK (April 2007). "Identification of small RNAs in diverse bacterial species". Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10 (2): 96–101. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.005. PMID 17383222. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, et al. (June 1998). "Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence". Nature 393 (6685): 537–44. doi:10.1038/31159. PMID 9634230.

- Arnvig KB, Gopal B, Papavinasasundaram KG, Cox RA, Colston MJ (February 2005). "The mechanism of upstream activation in the rrnB operon of Mycobacterium smegmatis is different from the Escherichia coli paradigm". Microbiology (Reading, Engl.) 151 (Pt 2): 467–73. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27597-0. PMID 15699196.

- Matsunaga I, Bhatt A, Young DC, et al. (December 2004). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis pks12 Produces a Novel Polyketide Presented by CD1c to T Cells". J. Exp. Med. 200 (12): 1559–69. doi:10.1084/jem.20041429. PMC 2211992. PMID 15611286. Retrieved 2010-09-01.