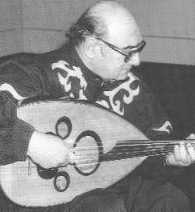

Munir Bashir

| Munir Bashir | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Native name |

منير بشير ܡܘܢܝܪ ܒܫܝܪ |

| Born | 1930[1] |

| Origin | Mosul, Iraq |

| Died |

September 1997 (aged 66–67) Budapest, Hungary |

| Genres | Middle Eastern music |

| Occupations | Musician |

| Instruments | lute, oud |

| Years active | 1953–1997 |

| Notable instruments | |

| Oud | |

Munir Bashir, the King of Oud (Arabic: منير بشير, Syriac: ܡܘܢܝܪ ܒܫܝܪ) (1930 – September 28, 1997) was an Assyrian Iraqi musician and one of the most famous musicians in the Middle East during the 20th century and was considered to be the supreme master of the Arab maqamat scale system.[2]

He created different styles of the Arabian short scaled lute, the oud. He was one of the first middle eastern instrumentalists known to Europe and America. Bashir’s music is distinguished by a novel style of improvisation that reflects his study of Indian and European tonal art in addition to oriental forms.[3] Born in Iraq, he had to deal with numerous disruptions of violent coup attempts and multiple wars that the country went through. He would eventually exile to Europe and become noticeable first in eastern nations such as Hungary and Bulgaria.

Life

Early life

Munir Bashir was born in Mosul, situated in northern Iraq.[4] According to different references he was born in a period of time from 1928 to 1930. Bashir is descended from a family of Assyrian heritage.[5] His father Abd al-Aziz and his brother Jamil had good reputations as oud-soloists and vocalists; Jamil wrote an important textbook for the oud. The family started musically educating young Bashir at his age of five, Bashir's father began to instruct him and his older brother Jamil in the basics of ud. His father, who was also a poet believed that a pure tradition of Arab music had devolved in Baghdad.[3][6] He first learned to play the violoncello, a European instrument that had become a popular bass-instrument in Arabian music during the end of the 19th century. He simultaneously was taught playing the oud. The lute plays a similar role in Arabian music as the piano does in European music: it is the instrument used to impart the most important theoretical aspects in music.

Due to a blend of many different styles and traditions there is a rich musical history in northern Iraq. In this milieu Bashir came in contact with Byzantine, Kurdish, Assyrian, Turkish, Persian, and traditional Abbasidian music.

Moving to Baghdad

At the age of six talented Bashir was sent to the Baghdad Conservatory, founded 1934 by the distinguished Iraqi musicologist Scharif Muhyi ad-Din Haydar Targan (1892 – 1967). Already during his studies, but especially after his degree, Bashir paid his attention to documenting and preserving the traditional musical styles of his country. Due to the turbulent Iraqi history and other reasons these styles were overridden by “Western” ones, especially commercial ones.

In 1951, Bashir took a teaching assignment at the new founded Académie des Beaux-Arts in Baghdad, besides his editorial work for the Iraqi broadcasting.[7]

Exploring outside of Iraq

Bashir always had an ambivalent relationship to his country: On the one side he felt deeply rooted in the rich cultural heritage of Mesopotamia, on the other side the Iraq had no phases of inner stability during the musicians lifetime. Especially the 1950s and 1960s — the last years of the Hashemite monarchy and a time of military coups following the fall of Faisal II. in 1958 — forced Bashir to work abroad.

His reputation had already arrived in Beirut, therefore he was contracted as accompany and "star-soloist" by the legendary Lebanese chanteuse Fairuz immediately when he arrived at the Lebanese capital in 1953. He got to know US and Latino American popular music but intensified his attempts of investigating Middle Eastern musical traditions. Due to his profound musicological knowledge he gained teaching assignments at the musical colleges of Baghdad and Beirut.

The years 1953 and 1954 marked the beginning of Bashir's career as an instrument virtuoso. His first concert as a soloist took place 1953 in Istanbul, in the next year the 24-year-old was featured in Iraqi television. 1957 he started several tours leading him to most of the European countries. The difficult political status of his country and the resulting problematic working parameters for musicians forced him to leave the country permanently.

Budapest

After a sojourn in Beirut, Bashir settled down in Budapest in the beginning 1960s, where he established a place of residence until his death. He married a Hungarian, his son Omar bashir was born 1970 in the Hungarian capital.[7] His son went on to be a musician as well.[8] This city was attractive for the Iraqi not only because of its status as European music metropolis, but for giving him the opportunity to study at the Franz Liszt Conservatory under supervision of Zoltán Kodály, where he did his doctorate in musicology in 1965.[3] Kodály had rendered outstanding services to the preservation of traditional Hungarian songs in collaboration with Béla Bartók. This well corresponded to Bashir’s aims and methods concerning his engagement for traditional folk music of his home country.

After Kodály’s death in 1967 Bashir spent some time in Beirut again. But he was repelled by the development of the Arabian music, which was marked by progressive degeneration and commercialisation, due to the incompetent and uncritical dealing with western influences. Considering, that the popular chanters were responsible for these trends, he refused to take engagements from them.

Messenger of Iraqi music

In 1973, the Iraqi ministry of information appointed Bashir to its culture committee;[7] the regime of the Baath party was not well established at that time and made Bashir to a cultural figure of integration of the Christian minority. Also because of his international popularity, Bashir, who rather presented himself apolitical, seemed to be a suited personality for representing the different ethnic, religious, and political groups of his home country. In 1981 — Saddam Hussein was already in power and the actual forces passing over to the Sunnites — the regime also supports the formation of Bashir’s Iraqi Traditional Music Group that dedicates itself to the diversity of the Iraqi culture.

In 1987 — during the Iran–Iraq War — Bashir succeeded in realising a long-cherished project: For the first time the Babylon International Festival of dance, music, and theatre, which Bashir was leading for several years, took place.

But Bashir himself rarely spent his time in Baghdad and finally left the country after the First Gulf War in 1991. Guest performances mainly in Europe offered him a big open-minded audience, and therefore an excellent platform for the presentation of his meanwhile very original and mature style of improvisation and composition. Most of his records were also recorded in Europe. In his last years he aimed at making his son Omar his musical successor. A duo-recording of Bashir and Omar made in February 1994 is considered to be a classic of Bashir’s Œuvre, because of its exemplary combination of traditional – mainly folk – material mixed with improvisation.

Munir Bashir died of heart failure in 1997 in Budapest at the age of 68, a short time before his planned departure to his Mexican tour.[3]

Instrumental style

General characteristics

In the long history of the oud, Munir Bashir is one of the most important players.[9] His style noticeably differs from other oud-players, for example from the urban “showmanship” in the “typical Egyptian” style of Farid Al Attrach, or from the heavily jazz-oriented music of Lebanese Rabih Abou-Khalil, who is very popular in Europe.

Especially in the field of soloistic improvisation (taqsīm) over the common scales (maqām) in Arabian music, his colleagues considered him to be an unsurpassed master.[3] It surely attributes to Bashir’s pioneering work, that nowadays oud-players are able to give solo-concerts all over the world.

But during his musical development he fought against the cliché, that the oud is the oriental equivalent to the condescendingly smiled at western “campfire guitar”.

Tunings

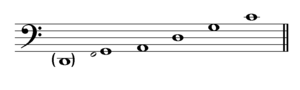

In many musical idioms it belongs to the tradition of stringed instruments to work with different tunings, adapted to the demands of the piece of music. Therefore it is not surprising, that Bashir experimented with a lot of tunings. A common tuning of the Arabian oud — “Arabian” in contrast to the almost identical Turkish instrument, that has a slightly different history — is:

Based on older traditions of the Iraqi oudist-school (for example the one of his older brother) Munir Bashir developed a typical tuning, that is named after him:

Noticeable is the doubling of the actual “highest” course in F by another one, that is higher, but is tuned one octave lower. This trick enables a special full sound of the high melody course and complies with Bashir’s interest in melodic forms.

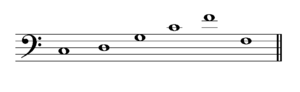

Another tuning of this kind was developed by members of the Bashir family: The player uses an F-course on the bass strings, tuned another octave lower as in the above mentioned example; optional two F-strings can be put on, tuned in an octave-interval. Using this special tuning the melody course in the center of the fingerboard is framed by the bass courses. Tuned this way the oud has a really full sound and enables unusual melodies, but such a complex tuning system makes high demands on the picking and stopping techniques of the musician.

Picking technique

As with other instruments of the lute-family (among such different instruments like the mandolin and the sitar) the player makes the sound by picking the strings with a plectrum (pick). The Arabian term for the pick is reesha, which originally was made of a pinfeather of an eagle. One impressive aspect of Bashir was the precision of his risha. His style emphasized a clean risha, while most other oud players have a heavy risha.[10] The reesha is held in the palm of one’s hand, resulting in a difficultly learnable picking technique; furthermore the doubled strings have a less controllable attack than single strings.

Therefore the inevitable rhythmic reliability in fastest, asymmetric accented, melodies is a special trademark of virtuosos. Generalizing: Arabian music is much more interested in rhythmical patterns that are more complex than European ones. Bashir's virtuosity of picking can easily be understood, when he shows his ability to apply the abovementioned scordatura, with its string pairs tuned in octaves, in an improvisation in the fast 10/8 metre, without the immense stopping problems of this method becoming hearable.

Bashir's dealing with foreign musical forms appears also in his experiments with alternative picking techniques. He made the fingerpicking, cultivated on the guitar — especially in flamenco — to an essential attribute of his mature style. But after a few experiments, he gave up using a thumb-plectrum (mizrab) that he got to know during his studies of the Indian sitar.

Ornamentation

Bashir's preferred improvisational type, the taqsim improvisation pulls its attractiveness out of the intelligent and strictly regulated ornamentation of melodies or familiar melodic fragments. Therefore a taqsim evolves out of different, but less artful criteria, than in modern jazz, where an improvisation takes place inside of a relatively strict metric, harmonic, and formal raster. But similar to jazz-improvisation, some distinct patterns can be assigned to their originator. On this note, a connoisseur of Arabian music is able to recognize a lot of “bashirisms”, analogue to a jazz-fan, who undoubtedly identifies the influence of Louis Armstrong or Charlie Parker in special melodic phrases.

Expansion of the ambitus

As mentioned above, the oud belongs to the family of short scale lutes. The widest interval that can be stopped between the open string and the end of the fingerboard is a fifth (quint); though it is possible to play wider intervals on the same string by stopping tones on the top of the corpus. Although Bashir has not invented this slightly unorthodox technique, he has integrated it into his style in an exemplary manner.

Also, before Bashir, the usage of flageolets did not belong to the traditional playing techniques of the oud, even though this technique actually is characteristic for stringed instruments.

Foreign influences

Bashir's occasionally polemic engagement for the authentic means of expression of Arabian music not only resulted from a rigorous inner view. He was a comprehensive educated and interested musician, who showed a notedly open-mindedness for non-Arabian styles in his lifetime; whereas he paid special attention to European and northern Indian (Hindu music.)[11]

This profound knowledge enabled him to incorporate foreign influences into his music not as incoherent quotations, but to include them in a convincing way.

Bashir's working mode is pointed out with an extra spectacular example: His composition Al-Amira al-Andaluciyya (“The Princess of Andalusia”), that can be heard on the duo-recording of Bashir and his son Omar, has an opening motif that is very unusual for its Arabian context.

The C-major arpeggio (motif a) that opens the piece would be an extra banal phrase in European music, but played on the oud it represents a totally unusual musical gesture, because there are no such major triads of that form used in Arabian music. Then the playing around the note C (motif b) points to the musical connotation (Andalusia, for centuries a province of the caliphate, and homeland of the flamenco), that was intended by the composer. With the help of only two notes (Db and Bb) the major triad changes into the Phrygian mode that is very typical for the flamenco, whereas the tremolo-like ornamentation of the leading Db supports this effect. Then the line descending to G (motif c) establishes the key for the further improvisations. This key is called maqam Hijaz Kar Kurd and has the following (simplified) structure:

The asymmetric setup of this scale requires a different leading of the ascending and descending melody lines, and is well suited for flamenco-like improvisations, because the flamenco style is characterized by a typical ambivalent and unstable reference to the major/minor-tonality. The last one naturally is unknown to Arabian music that has no harmony.

During the progressing improvisations Bashir uses another virtuosity effect by playing many chords. These so-called rasgueados are an indispensable element of style of the flamenco guitar. But on the fretless oud it is very difficult to intonate them correctly.

Influences and reception

Relevance for Arabian music

Munir Bashir emerged into the scene at a time that was anything but fortunate for Arabian music. Because of his professional experiences he was more conscious of these difficulties than many of his colleagues, who often tended towards retreating into niches or more or less resignedly accepting these conditions. Bernard Lewis, the British historian, refers to the musician as an example of a Middle Eastern, who has understood to meet the influence of the Western culture on the basis of equal collaboration. Bashir sought and found new possibilities of musical expression by standing up for the traditions of “his” music and by dealing with older forms.

On a more technical level, Bashir put his improvisations in the context of maqamat, which were never used outside of Iraq, or which fell into obscurity during the 20th century.

Criticism

Bashir's integration of foreign elements of style led to a lack of understanding and criticism of the traditionalists. As reported by the music journalist Sami Asmar, Bashir was accused of chumming up to his western audience by preferentially making music in extra simple maqamat. It was explicitly stated that Bashir abuses the maqamat Rast and Shadd Araban that way.[7]

Maqam Rast |

Maqam Shadd Araban |

Indeed it is right, that maqam Rast is a very basic scale in Arabian music, comparable to C-Major in western music. For western listeners this tonality — approximately the Dorian scale with quartertone intervals — is anything else but catchy. In Shadd Araban it is the use of two 1½ intervals, that makes the scale abstractly sounding for western ears.

Apart from the sparsely convincing assumptions on which these criticisms are based, those are not supported by Bashir's recordings. In these recordings there are no signs of a preference for the aforementioned scales, and there is no evidence for other behaviour at Bashir's live performances. In contrast it is more easily verifiable that Bashir preferred even such scales, which enabled huge melodic freedom, and which implicate a strong tonal ambivalence for the European ear that is used to harmony – as shown above for the Hijaz Kar Kurd.

Honours

Bashir, especially in his latter years, received international honors for his musical opus and his engagement for the dialog of cultures. Amongst others he was vice president of the UNESCO International Music Council,[12] knight of the French Legion of Honour, and secretary general of the Arabian music academy in Baghdad.

Discography

- Recital – Solo de Luth Oud, Live in Geneva

- Munir Bashir & the Iraqi Traditional Music Group

- Recital; Solo de Luth Oud (Live in Geneva)

- Maqamat

- En Concert a Paris (Live in Paris)

- Meditations

- Flamenco Roots

- Concert in Budapest

- Raga Roots

- Oud Around the Arab World

- The Stockholm Recordings

- Duo de 'Ud (with Omar Bashir)

- L'Art du 'Ud (The Art of the Ud)

Literature

- Sami Asmar: The Musical Legacies Of Sayyid Makkawi, Munir Bashir and Walid Akel. in: Al-Jadid. A Review and Record of Arab culture and arts. Los Angeles 4.1998, H 23.

- Habib Hassan Touma (1996). The Music of the Arabs, trans. Laurie Schwartz. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

References

- ↑ Colors of Enchantment: Theater, Music and the Visual Arts of the Middle East By SHERIFA ZUHUR, ED.- Page 312

- ↑ World Music: The Rough Guide, by Simon Broughton, Mark Ellingham, Richard Trillo, 1999.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Colors of Enchantment: Theater, Music and the Visual Arts of the Middle East, By Sherifa Zuhur, 2001

- ↑ "National Geographic World Music: Munir Bashir". Worldmusic.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ "Munir Bashir : National Geographic World Music". Worldmusic.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ Colors of Enchantment: Theater, Music and the Visual Arts of the Middle East By SHERIFA ZUHUR, ED.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 The Musical Legacies Of Sayyid Makkawi, Munir Bashir and Walid Akel, by Sami Asmar

- ↑ "Omar Bashir Musician Website v2.1". Omarbashir.hu. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ http://www.rahimalhaj.com/about.htm

- ↑ Julien Weiss Discusses Traditional and Contemporary Arab Music, by Sami Asmar

- ↑ "New Releases 10/5/2001". Downtownmusicgallery.com. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ "International Music Council". Unesco.org. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

External links

Music theory, biography

- Munir Bashir International Foundation

- Munir Bashir Discography & Music

- Website of the oud-expert Dr. David Parfitt

- Comprehensive website about the oud

- Excellent, easy to understand introduction of Arabian music theory

- Encyclopedia of the Orient

- Saramusik

- Painting of swiss artist Otto Kohler

Audio samples

|