Mumia Abu-Jamal

| Mumia Abu-Jamal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Wesley Cook April 24, 1954 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment without parole |

Criminal status | Incarcerated |

| Conviction(s) | First degree murder |

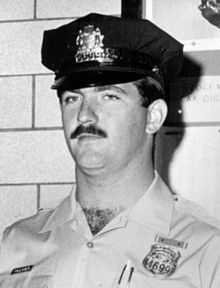

Mumia Abu-Jamal (born Wesley Cook[2] on April 24, 1954) is an American radical convicted for the 1981 murder of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner.[3] His original sentence of death, handed down at his first trial in July 1982, was commuted to life imprisonment without parole in 2012.[4] Described as "perhaps the world's best known death-row inmate" by The New York Times,[5] supporters and detractors have disagreed on his guilt, whether he received a fair trial, and the appropriateness of the death penalty.[6][7][8]

Born in Philadelphia, Abu-Jamal became involved in black nationalism in his youth, and was a member of the Black Panther Party until October 1970. Alongside his political activism, he became a radio journalist, eventually becoming president of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists. On December 9, 1981, Officer Faulkner was shot dead while conducting a traffic stop on Abu-Jamal's brother, William Cook. Abu-Jamal was injured by a shot from Faulkner and when further police arrived on the scene, he was arrested and charged with first degree murder.

Going on trial in 1982, he initially decided to represent himself, but was repeatedly reprimanded for disruptive behavior and given a court-appointed lawyer. Three witnesses testified that they had witnessed Abu-Jamal commit the murder, and he was unanimously convicted by jury and sentenced to death, spending the next 30 years on death row. In 2008, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the murder conviction but ordered a new capital sentencing hearing because the jury was improperly instructed.[9] Subsequently, the United States Supreme Court also allowed his conviction to stand,[9] but ordered the appeals court to reconsider its decision as to the sentence.[10] In 2011, the Third Circuit again affirmed the conviction as well as its decision to vacate the death sentence,[11] and the District Attorney of Philadelphia announced that prosecutors would no longer seek the death penalty.[12] He was removed from death row in January 2012, and in March 2012 the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled that all claims of new evidence put on his behalf did not warrant conducting a retrial.

During his imprisonment he has published several books and other commentaries, notably Live from Death Row (1995), in which he dealt with social and political issues.

Early life and activism

Abu-Jamal was given the name Mumia in 1968 by his high school teacher, a Kenyan instructing a class on African cultures in which students took African classroom names.[13] According to Abu-Jamal, 'Mumia' means "Prince" and was the name of Kenyan anti-colonial African nationalists who fought against the British before Kenyan independence.[14] He adopted the surname Abu-Jamal ("father of Jamal" in Arabic) after the birth of his son Jamal on July 18, 1971.[13][15] His first marriage at age 19, to Jamal's mother, Biba, was short-lived.[16] Their daughter, Lateefa, was born shortly after the wedding.[17] Abu-Jamal married his second wife, Marilyn (known as "Peachie"),[15] in 1977.[18] Their son, Mazi, was born in early 1978.[19] By 1981, Abu-Jamal was living with his third and current wife, Wadiya.[18]

Involvement with the Black Panthers

In his own writings, Abu-Jamal describes his adolescent experience of being "kicked ... into the Black Panther Party" after suffering a beating from "white racists" and a policeman for his efforts to disrupt a George Wallace for President rally in 1968.[20] From the age of 14, he helped form the Philadelphia branch of the Black Panther Party,[21] taking appointment, in his own words, as the chapter's "Lieutenant of Information", exercising a responsibility for writing information and news communications. In one of the interviews he gave at the time he quoted Mao Zedong, saying that "political power grows out of the barrel of a gun".[22] That same year, he dropped out of Benjamin Franklin High School and took up residence in the branch's headquarters.[21] He spent late 1969 in New York City and early 1970 in Oakland, living and working with BPP colleagues in those cities.[23] He was a party member from May 1969 until October 1970 and was subject to Federal Bureau of Investigation COINTELPRO surveillance, with which the Philadelphia police cooperated,[24] from then until about 1974.[25]

Education and journalism career

After leaving the Panthers he returned to his old high school, but was suspended for distributing literature calling for "black revolutionary student power".[26] He also led unsuccessful protests to change the school name to Malcolm X High.[26] After attaining his GED, he studied briefly at Goddard College in rural Vermont.[27]

By 1975 he was pursuing a vocation in radio newscasting, first at Temple University's WRTI and then at commercial enterprises.[26] In 1975, he was employed at radio station WHAT and he became host of a weekly feature program of WCAU-FM in 1978.[28] He was also employed for brief periods at radio station WPEN, and became active in the local chapter of the Marijuana Users Association of America.[28] From 1979 he worked at National Public Radio-affiliate WUHY until 1981 when he was asked to submit his resignation after a dispute about the requirements of objective focus in his presentation of news.[28] As a radio journalist he earned the moniker "the voice of the voiceless" and was renowned for identifying with and giving exposure to the MOVE anarcho-primitivist commune in Philadelphia's Powelton Village neighborhood, including reportage of the 1979–80 trial of certain of its members (the "MOVE Nine") charged with the murder of police officer James Ramp.[28] During his broadcasting career, his high-profile interviews included Julius Erving, Bob Marley and Alex Haley, and he was elected president of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists.[29]

At the time of Daniel Faulkner's murder, Abu-Jamal was working as a taxicab driver in Philadelphia two nights a week to supplement his income.[29] He had been working part-time as a reporter for WDAS,[28] then an African-American-oriented and minority-owned radio station.[30]

Arrest for murder and trial

On December 9, 1981, in Philadelphia, close to the intersection at 13th and Locust Streets, Philadelphia Police Department officer Daniel Faulkner conducted a traffic stop on a vehicle belonging to William Cook, Abu-Jamal's younger brother. During the traffic stop, Abu-Jamal's taxi was parked across the street, and Abu-Jamal ran across the street towards the traffic stop. At the traffic stop, there was an exchange of fire. Both Officer Faulkner and Abu-Jamal were wounded, and Faulkner died. Police arrived on the scene and arrested Abu-Jamal, who was found wearing a shoulder holster. A revolver, which had five spent cartridges, was beside him. He was taken directly from the scene of the shooting to Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, where he received treatment for his wound, the result of a shot from Faulkner.[31]

Abu-Jamal was charged with the first-degree murder of Daniel Faulkner. The case went to trial in June 1982 in Philadelphia. Judge Albert F. Sabo initially agreed to Abu-Jamal's request to represent himself, with criminal defense attorney Anthony Jackson acting as his legal advisor. During the first day of the trial, Judge Sabo warned Abu-Jamal that he would forfeit his legal right to self-representation if he kept being intentionally disruptive in a fashion that was unbecoming under the law. Due to Abu-Jamal's continued disruptive behavior, Judge Sabo ruled that Abu-Jamal forfeited his right to self-representation.[32]

Prosecution case at trial

The prosecution presented four witnesses to the court. Robert Chobert, a cab driver who testified he was parked behind Faulkner, identified Abu-Jamal as the shooter.[33] Cynthia White, a prostitute, testified that Abu-Jamal emerged from a nearby parking lot and shot Faulkner.[34] Michael Scanlan, a motorist, testified that from two car lengths away, he saw a man, matching Abu-Jamal's description, run across the street from a parking lot and shoot Faulkner.[35] Albert Magilton, a pedestrian who did not see the actual murder, testified to witnessing Faulkner pull over Cook's car. At the point of seeing Abu-Jamal start to cross the street toward them from the parking lot, Magilton turned away and lost sight of what happened next.[36]

The prosecution also presented two witnesses who were at the hospital after the altercation. Hospital security guard Priscilla Durham and police officer Garry Bell testified that Abu-Jamal confessed in the hospital by saying, "I shot the motherfucker, and I hope the motherfucker dies."[37]

A .38 caliber Charter Arms revolver, belonging to Abu-Jamal, with five spent cartridges was retrieved beside him at the scene. He was wearing a shoulder holster, and Anthony Paul, the Supervisor of the Philadelphia Police Department's firearms identification unit, testified at trial that the cartridge cases and rifling characteristics of the weapon were consistent with bullet fragments taken from Faulkner's body.[38] Tests to confirm that Abu-Jamal had handled and fired the weapon were not performed, as contact with arresting police and other surfaces at the scene could have compromised the forensic value of such tests.[39][40]

Defense case at trial

The defense maintained that Abu-Jamal was innocent and that the prosecution witnesses were unreliable. The defense presented nine character witnesses, including poet Sonia Sanchez, who testified that Abu-Jamal was "viewed by the black community as a creative, articulate, peaceful, genial man".[41] Another defense witness, Dessie Hightower, testified that he saw a man running along the street shortly after the shooting although he did not see the actual shooting itself.[42] His testimony contributed to the development of a "running man theory", based on the possibility that a "running man" may have been the actual shooter. Veronica Jones also testified for the defense, but she did not see anyone running.[43] Other potential defense witnesses refused to appear in court.[44] Abu-Jamal did not testify in his own defense. Nor did his brother, William Cook, who told investigators at the crime scene: "I ain't got nothing to do with this."[45]

Verdict and sentence

The jury delivered a unanimous guilty verdict after three hours of deliberations.

In the sentencing phase of the trial, Abu-Jamal read to the jury from a prepared statement. He was then cross-examined about issues relevant to the assessment of his character by Joseph McGill, the prosecuting attorney.[46]

In his statement Abu-Jamal criticized his attorney as a "legal trained lawyer" who was imposed on him against his will and who "knew he was inadequate to the task and chose to follow the directions of this black-robed conspirator, [Judge] Albert Sabo, even if it meant ignoring my directions". He claimed that his rights had been "deceitfully stolen" from him by Sabo, particularly focusing on the denial of his request to receive defense assistance from non-attorney John Africa and being prevented from proceeding pro se. He quoted remarks of John Africa, and said:

Does it matter whether a white man is charged with killing a black man or a black man is charged with killing a white man? As for justice when the prosecutor represents the Commonwealth the Judge represents the Commonwealth and the court-appointed lawyer is paid and supported by the Commonwealth, who follows the wishes of the defendant, the man charged with the crime? If the court-appointed lawyer ignores, or goes against the wishes of the man he is charged with representing, whose wishes does he follow? Who does he truly represent or work for? ... I am innocent of these charges that I have been charged of and convicted of and despite the connivance of Sabo, McGill and Jackson to deny me my so-called rights to represent myself, to assistance of my choice, to personally select a jury who is totally of my peers, to cross-examine witnesses, and to make both opening and closing arguments, I am still innocent of these charges.[47]

Abu-Jamal was subsequently sentenced to death by the unanimous decision of the jury.[48]

Appeals and review

State appeals

Direct appeal of his conviction was considered and denied by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on March 6, 1989,[49] subsequently denying rehearing.[50] The Supreme Court of the United States denied his petition for writ of certiorari on October 1, 1990,[51] and denied his petition for rehearing twice up to June 10, 1991.[52][53]

On June 1, 1995, his death warrant was signed by Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge.[53] Its execution was suspended while Abu-Jamal pursued state post-conviction review. At the post-conviction review hearings, new witnesses were called. William "Dales" Singletary testified that he saw the shooting and that the gunman was the passenger in Cook's car.[54] Singletary's account contained discrepancies which rendered it "not credible" in the opinion of the court.[53][55] William Harmon, a convicted fraudster, testified that Faulkner's murderer fled in a car which pulled up at the crime scene, and could not have been Abu-Jamal.[56] However, Robert Harkins testified that he had witnessed a man stand over Faulkner as the latter lay wounded on the ground, who shot him point-blank in the face and then "walked and sat down on the curb".[57][58]

The six judges of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled unanimously that all issues raised by Abu-Jamal, including the claim of ineffective assistance of counsel, were without merit.[59] The Supreme Court of the United States denied a petition for certiorari against that decision on October 4, 1999, enabling Ridge to sign a second death warrant on October 13, 1999. Its execution in turn was stayed as Abu-Jamal commenced his pursuit of federal habeas corpus review.[53]

In 1999, Arnold Beverly claimed that he and an unnamed assailant, not Mumia Abu-Jamal, shot Daniel Faulkner as part of a contract killing because Faulkner was interfering with graft and payoff to corrupt police.[60] The Beverly affidavit became an item of division for Mumia's defense team, as some thought it usable and others rejected Beverly's story as "not credible".[61]

Private investigator George Newman claimed in 2001 that Chobert had recanted his testimony.[62] Commentators also noted that police and news photographs of the crime scene did not show Chobert's taxi, and that Cynthia White, the only witness at the trial to testify to seeing the taxi, had previously provided crime scene descriptions that omitted it.[63] Cynthia White was declared to be dead by the state of New Jersey in 1992 although Pamela Jenkins claimed that she saw White alive as late as 1997.[64] Mumia supporters often claim that White was a police informant and that she falsified her testimony against Abu-Jamal.[65] Priscilla Durham's step-brother, Kenneth Pate, who was imprisoned with Abu-Jamal on other charges, has since claimed that Durham admitted to not hearing the hospital confession.[66] The hospital doctors stated that Abu-Jamal was "on the verge of fainting" when brought in and they did not overhear a confession.[67] In 2008, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rejected a further request from Abu-Jamal for a hearing into claims that the trial witnesses perjured themselves on the grounds that he had waited too long before filing the appeal.[68]

On March 26, 2012 the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rejected his most recent appeal for retrial asserted on the basis that a 2009 report by the National Academy of Science demonstrated that forensic evidence put by the prosecution and accepted into evidence in the original trial was unreliable.[69][70] It was reported to be the former death row inmate's last legal appeal. [71]

Federal ruling directing resentencing

Abu-Jamal did not make any public statements about Faulkner's murder until May 2001. In his version of events, he claimed that he was sitting in his cab across the street when he heard shouting, then saw a police vehicle, then heard the sound of gunshots. Upon seeing his brother appearing disoriented across the street, Abu-Jamal ran to him from the parking lot and was shot by a police officer.[72] The driver originally stopped by police officer Faulkner, Abu-Jamal's brother William Cook, did not testify or make any statement until April 29, 2001, when he claimed that he had not seen who had shot Faulkner.[73]

Judge William H. Yohn Jr. of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania upheld the conviction but vacated the sentence of death on December 18, 2001, citing irregularities in the original process of sentencing.[53] Particularly,... the jury instructions and verdict sheet in this case involved an unreasonable application of federal law. The charge and verdict form created a reasonable likelihood that the jury believed it was precluded from considering any mitigating circumstance that had not been found unanimously to exist.[53]He ordered the State of Pennsylvania to commence new sentencing proceedings within 180 days[74] and ruled that it was unconstitutional to require that a jury's finding of circumstances mitigating against determining a sentence of death be unanimous.[75] Eliot Grossman and Marlene Kamish, attorneys for Abu-Jamal, criticized the ruling on the grounds that it denied the possibility of a trial de novo at which they could introduce evidence that their client had been framed.[76] Prosecutors also criticized the ruling; Officer Faulkner's widow Maureen described Abu-Jamal as a "remorseless, hate-filled killer" who would "be permitted to enjoy the pleasures that come from simply being alive" on the basis of the judgment.[77] Both parties appealed.

Federal appeal

On December 6, 2005, the Third Circuit Court admitted four issues for appeal of the ruling of the District Court:[78]

- in relation to sentencing, whether the jury verdict form had been flawed and the judge's instructions to the jury had been confusing;

- in relation to conviction and sentencing, whether racial bias in jury selection existed to an extent tending to produce an inherently biased jury and therefore an unfair trial (the Batson claim);

- in relation to conviction, whether the prosecutor improperly attempted to reduce jurors' sense of responsibility by telling them that a guilty verdict would be subsequently vetted and subject to appeal; and

- in relation to post-conviction review hearings in 1995–6, whether the presiding judge, who had also presided at the trial, demonstrated unacceptable bias in his conduct.

The Third Circuit Court heard oral arguments in the appeals on May 17, 2007, at the United States Courthouse in Philadelphia. The appeal panel consisted of Chief Judge Anthony Joseph Scirica, Judge Thomas Ambro, and Judge Robert Cowen. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania sought to reinstate the sentence of death, on the basis that Yohn's ruling was flawed, as he should have deferred to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court which had already ruled on the issue of sentencing, and the Batson claim was invalid because Abu-Jamal made no complaints during the original jury selection. Abu-Jamal's counsel told the Third Circuit Court that Abu-Jamal did not get a fair trial because the jury was both racially-biased and misinformed, and the judge was a racist.[79] The last of those claims was made based on the statement by a Philadelphia court stenographer named Terri Maurer-Carter who, in a 2001 affidavit, stated that Judge Sabo had said "Yeah, and I'm going to help them fry the nigger" in the course of a conversation regarding Abu-Jamal's case.[80] Sabo denied having made any such comment.[81]

On March 27, 2008, the three-judge panel issued a majority 2–1 opinion upholding Yohn's 2001 opinion but rejecting the bias and Batson claims, with Judge Ambro dissenting on the Batson issue. On July 22, 2008, Abu-Jamal's formal petition seeking reconsideration of the decision by the full Third Circuit panel of 12 judges was denied.[82] On April 6, 2009, the United States Supreme Court also refused to hear Abu-Jamal's appeal.[9] On January 19, 2010, the Supreme Court ordered the appeals court to reconsider its decision to rescind the death penalty,[10][83] with the same three-judge panel convening in Philadelphia on November 9, 2010, to hear oral argument.[84][85] On April 26, 2011, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals reaffirmed its prior decision to vacate the death sentence on the grounds that the jury instructions and verdict form were ambiguous and confusing.

Death penalty dropped

On December 7, 2011, Philadelphia District Attorney R. Seth Williams announced that prosecutors would no longer seek the death penalty for Abu-Jamal.[12] Williams said that Abu-Jamal will spend the rest of his life in prison without the possibility of parole,[86] a sentence that was duly reaffirmed by the Superior Court of Pennsylvania on July 9, 2013.[87]

Life as a prisoner

In 1991 Abu-Jamal published an essay in the Yale Law Journal, on the death penalty and his Death Row experience.[88] In May 1994, Abu-Jamal was engaged by National Public Radio's All Things Considered program to deliver a series of monthly three-minute commentaries on crime and punishment.[89] The broadcast plans and commercial arrangement were canceled following condemnations from, among others, the Fraternal Order of Police[90] and US Senator Bob Dole (R-Kan.).[91] Abu-Jamal sued NPR for not airing his work, but a federal judge dismissed the suit.[92] The commentaries later appeared in print in May 1995 as part of Live from Death Row.[93]

In 1999, he was invited to record a keynote address for the graduating class at The Evergreen State College. The event was protested by some.[94] In 2000, he recorded a commencement address for Antioch College.[95] The now defunct New College of California School of Law presented him with an honorary degree "for his struggle to resist the death penalty".[96]

With occasional interruptions due to prison disciplinary actions, Abu-Jamal has for many years been a regular commentator on an online broadcast, sponsored by Prison Radio,[97] as well as a regular columnist for Junge Welt, a Marxist newspaper in Germany. In 1995, he was punished with solitary confinement for engaging in entrepreneurship contrary to prison regulations. Subsequent to the airing of the 1996 HBO documentary Mumia Abu-Jamal: A Case For Reasonable Doubt?, which included footage from visitation interviews conducted with him, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections acted to ban outsiders from using any recording equipment in state prisons.[27] In litigation before the US Court of Appeals in 1998 he successfully established his right to write for financial gain in prison. The same litigation also established that the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections had illegally opened his mail in an attempt to establish whether he was writing for financial gain.[98] When, for a brief time in August 1999, he began delivering his radio commentaries live on the Pacifica Network's Democracy Now! weekday radio newsmagazine, prison staff severed the connecting wires of his telephone from their mounting in mid-performance.[27]

His publications include Death Blossoms: Reflections from a Prisoner of Conscience, in which he explores religious themes, All Things Censored, a political critique examining issues of crime and punishment, Live From Death Row, a diary of life on Pennsylvania's death row, and We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party, which is a history of the Black Panthers drawing on autobiographical material.

At the end of January 2012 he was released into general prison population at State Correctional Institution – Mahanoy.[99]

Popular support and opposition

Labor unions,[100][101][102] politicians,[8][103] advocates,[104] educators,[105] the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,[26] and human rights advocacy organizations such as Human Rights Watch[106] and Amnesty International have expressed concern about the impartiality of the trial of Abu-Jamal,[6] though Amnesty International neither takes a position on the guilt or innocence of Abu-Jamal nor classifies him as a political prisoner.[6] They are opposed by the family of Daniel Faulkner, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the City of Philadelphia,[107] Republican politicians,[107][108] and the Fraternal Order of Police.[109] In August 1999, the Fraternal Order of Police called for an economic boycott against all individuals and organizations that support Abu-Jamal.[110]

Abu-Jamal has been made an honorary citizen of about 25 cities around the world, including Copenhagen, Montreal, Palermo and Paris.[107][111] In 2001, he received the sixth biennial Erich Mühsam Prize, eponymously named after an anarcho-communist essayist, which recognizes activism in line with that of its namesake.[112] In October 2002, he was made an honorary member of the German political organization Society of People Persecuted by the Nazi Regime – Federation of Anti-Fascists (VVN-BdA)[113] which Germany's Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution has considered to be influenced by left-wing extremism.[114]

On April 29, 2006, a newly paved road in the Parisian suburb of Saint-Denis was named Rue Mumia Abu-Jamal in his honor.[115] In protest of the street-naming, US Congressman Michael Fitzpatrick (R-Pa.) and Senator Rick Santorum (R-Pa.) introduced resolutions in both Houses of Congress condemning the decision.[116][117] The House of Representatives voted 368–31 in favor of Fitzpatrick's resolution.[118] In December 2006, the 25th anniversary of the murder, the executive committee of the Republican Party for the 59th Ward of the City of Philadelphia—covering approximately Germantown, Philadelphia—filed two criminal complaints in the French legal system against the city of Paris and the city of Saint-Denis, accusing the municipalities of "glorifying" Abu-Jamal and alleging the offense "apology or denial of crime" in respect of their actions.[107][108]

In 2007, the widow of Officer Faulkner coauthored a book with Philadelphia radio journalist Michael Smerconish entitled Murdered by Mumia: A Life Sentence of Pain, Loss, and Injustice.[119] The book was part memoir of Faulkner's widow, part discussion in which they chronicled Abu-Jamal's trial and discussed evidence for his conviction, and part discussion on supporting the death penalty.[120] J. Patrick O'Connor, editor and publisher of crimemagazine.com, argues in his book The Framing of Mumia Abu-Jamal that the preponderance of evidence establishes that it was not Abu-Jamal but a passenger in Abu-Jamal's brother's car, Kenneth Freeman, who killed Faulkner, and that the Philadelphia Police Department and District Attorney's Office framed Abu-Jamal.[121] His book was criticized in the American Thinker as "replete with selective use of testimony, distortions, unsubstantiated charges, and a theory that has failed Abu-Jamal in the past."[122]

In 2010, investigative journalists Dave Lindorff and Linn Washington reproduced the shooting in tests that produced results they claimed were inconsistent with the case against Abu-Jamal; according to them, shots that missed Faulkner should have produced marks visible on the pavement. An expert photo analyst found no such marks visible in the highest-quality photo of the part of the crime scene where the body was found.[63] A ballistics expert medical examiner said the idea that police could have failed to recognise such marks at the crime scene was "absolute nonsense".[63] Abu-Jamal's lawyer said that the results constituted "extraordinarily important new evidence that establishes clearly that the prosecutor and the Philadelphia Police Department were engaged in presenting knowingly false testimony".[63]

Written works

- We Want Freedom: A Life In The Black Panther Party

- All Things Censored

- Live From Death Row

- Death Blossoms: Reflections From A Prisoner Of Conscience

- Jailhouse Lawyers: Prisoners Defending Prisoners V. The U.S.A

- Faith Of Our Fathers: An Examination Of The Spiritual Life Of African And African-American People

See also

- Alfonzo Giordano

- In Prison My Whole Life – 2008 documentary film

References

- ↑ "Justice For Daniel Faulkner T-Shirts". danielfaulkner.com. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Smith, Laura (October 27, 2007). "'I spend my days preparing for life, not for death'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Commonwealth v. Abu-Jamal, Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District, Philadelphia, Case Nos. 1357–59.

- ↑ "Mumia Abu-Jamal Case Back in Court Today". NBC Philadelphia. Associated Press. November 9, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ↑ Rimer, Sara (December 19, 2001). "Death Sentence Overturned In 1981 Killing of Officer". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "A Life in the Balance: The Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal". Amnesty International. February 17, 2000. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Taylor Jr., Stuart (December 1995). "Guilty and Framed". The American Lawyer. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "European Parliament resolution 9(f) B4-1170/95 (p. 39 of original, 49 of pdf)" (PDF). European Parliament. September 21, 1995. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Supreme Court lets Mumia Abu-Jamal's conviction stand". CNN. April 6, 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "U.S. court sends back Abu-Jamal death penalty case". Reuters.com. January 19, 2010.

- ↑ Dale, Maryclaire (April 26, 2009). "Mumia Abu-Jamal Granted New Sentencing Hearing". NBC. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Death Penalty Dropped Against Mumia Abu-Jamal". Associated Press (NPR). December 7, 2011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Burroughs, Todd Steven (2004). "Prologue: Joining the Party". Ready to Party: Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Black Panther Party. The College of New Jersey. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Abu-Jamal, Mumia (February 7, 2003). "Question for Mumia: Tell Me About Your Name". Mumia Abu-Jamal Radio Broadcast. Prison Radio. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Burroughs, Todd Steven (2004). "Part IV: Leaving the Party". Ready to Party: Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Black Panther Party. The College of New Jersey. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Bisson, p.119 quoted at "The Religious Affiliation of Mumia Abu-Jamal". Adherents.com. September 3, 2005. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Burroughs, Todd Steven (December 2001). "Mumia Abu-Jamal's Family Faces Future While Fighting Fear 20th Anniversary of 1981 Shooting Approaches". NNPA News Service. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Phelps, Christopher. "Abu-Jamal, Mumia". African American National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ See ages given in: Vann, Bill (April 27, 1999). "Tens of thousands rally in Philadelphia for political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal". World Socialist Web Site news. International Committee of the Fourth International. Retrieved 2008-01-22. and Erard, Michael (July 4, 2003). "A Radical in the Family". The Texas Observer. Archived from the original on 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Abu-Jamal, Mumia (1996). Live From Death Row. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-380-72766-7.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Burroughs, Todd Steven (2004). "Part I: "Do Something, Nigger!"". Ready to Party: Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Black Panther Party. The College of New Jersey. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Burroughs, Todd Steven (2004). "Epilogue: The Barrel of a Gun". Ready to Party: Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Black Panther Party. The College of New Jersey. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Burroughs, Todd Steven (2004). "Part II: The Party in Philadelphia". Ready to Party: Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Black Panther Party. The College of New Jersey. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ http://activistdefense.wordpress.com/2012/06/22/thirty-years-since-unfair-trial-of-journalist-and-author-mumia-abu-jamal/

- ↑ Burroughs, Todd Steven (2004). "Part III: 'Armed and Dangerous': Tracked by the FBI". Ready to Party: Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Black Panther Party. The College of New Jersey. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Shaw, Theodore M.; Chachkin, Norman J.; Swarns, Christina A. (July 27, 2007). "Brief of amicus curiae" (PDF). Mumia Abu-Jamal v. Martin Horn, Pennsylvania Director of Corrections, et al. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Archived from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Burroughs, Todd Steven (September 1, 2004). "Mumia's voice: confined to Pennsylvania's death row, Mumia Abu-Jamal remains at the center of debate as he continues to write and options to appeal his police murder conviction dwindle". Black Issues Book Review. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 "The Suspect – One Who Raised His Voice". The Philadelphia Inquirer. December 10, 1981. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 O'Connor, The Framing of Mumia Abu-Jamal, pp. 54–55

- ↑ "Philadelphia AM Radio History". Radio-History.com. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial and Post-Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) hearing transcripts" (PDF). Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript §1.72–§1.73". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 17, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript §3.210–§3.211". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 19, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp.94–95". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 21, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp.5–75". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 25, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp.75 ff.". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 25, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp.29, 31, 34, 137, 162 and 164". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 24, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript p.169". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 23, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Prosecution expert witness Charles Tumosa said such tests were "unreliable...It doesn't work if you grab a piece of metal like this or put your hand on a car or touch a firearm or touch a person who has touched a firearm or if you put your hand on the clean city streets or whatever." "Trial transcript, pp.57–61". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. June 26, 1982. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ↑ Defence expert witness George Fassnacht said "I don't know where he was grasped, but if you are saying that they had contacted his hands, particularly where a great deal of pressure was applied, they could have very well destroyed traces of powder residue if in fact such did exist. That is a possibility." "PCRA hearing transcript, pp.118–122". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 2, 1995. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript p.19". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 30, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript p.127". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 28, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp.99–100". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 29, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Post-Trial Motions transcript p.29". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. May 25, 1983. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Lopez, Steve (July 23, 2000). "Wrong Guy, Good Cause". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Trial transcript, pp.3–34". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia Criminal Trial Division. July 3, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript, pp.10–16". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia Criminal Trial Division. July 3, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript, pp.100–103". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia Criminal Trial Division. July 3, 1982. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Pennsylvania v. Abu-Jamal, 555 A.2d 846 (1989).

- ↑ Pennsylvania v. Abu-Jamal, 569 A.2d 915 (1990).

- ↑ Abu-Jamal v. Pennsylvania, 498 U.S. 881 (1990).

- ↑ Abu-Jamal v. Pennsylvania, 501 U.S. 1214 (1991).

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 53.5 Yohn, William H., Jr. (December 2001). "Memorandum and Order" (PDF). Mumia Abu-Jamal, Petitioner, vs. Martin Horn, Commissioner, Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, et al., Respondents. US District Court for the Eastern District of Philadelphia. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript pp.204 ff.". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 11, 1995. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript pp.16 ff.". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 14, 1995. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript pp.45 ff.". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 10, 1995. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of the Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trials Division. August 2, 1995. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Faulkner, Maureen (December 8–14, 1999). "Running From The Truth". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Pennsylvania v. Abu-Jamal, 720 A.2d 79 (1998).

- ↑ Beverly, Arnold (June 8, 1999). "Affidavit of Arnold Beverly". Justice for Police Officer Daniel Faulkner. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Lindorff, Dave (June 15, 2001). "Mumia's all-or-nothing gamble". Salon.com. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ↑ Newman, George Michael (September 25, 2001). Affidavit of George Michael Newman (rdf). Labor Action Committee to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 Dave Lindorff and Linn Washington, Jr, CounterPunch, 20 September 2010, Sidewalk Murder Scene Should Have Displayed Vivid Bullet Impact Marks

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript p.144". Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. June 26, 1997. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Williams, Yvette (January 28, 2002). Declaration of Yvette Williams. Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Pate, Kenneth (April 18, 2003). "Declaration of Kenneth Pate". Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Amnesty International The Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal: A Life in the Balance Seven Stories Press 2000 ISBN 158322081X p.25

- ↑ Lounsberry, Emilie (February 20, 2008). "Pa. court rebuffs Abu-Jamal on bid for perjury hearing". The Philadelphia Inquirer: B03.

- ↑ "Abu-Jamal Loses His Final Appeal". Associated Press. April 4, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ↑ "Order of Judgment by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, Eastern District, in Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v Mumia Abu-Jamal [J-44-2010]" (PDF). Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. March 26, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ↑ "Pa. Supreme Court rejects Mumia Abu-Jamal's last appeal". WPVI TV (abclocal.go.com). April 3, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- ↑ Abu-Jamal, Mumia (May 4, 2001). "Declaration of Mumia Abu-Jamal". Justice for Police Officer Daniel Faulkner. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Cook, William (April 29, 2001). "Declaration of William Cook". Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Abu-Jamal's death sentence overturned". BBC News. December 18, 2001. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ See p.70 of the July 2006 appeal brief for Abu-Jamal before the US Court of Appeal citing Yohn's ruling in the US District Court, the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and the United States Supreme Court precedent of Mills v. Maryland, 486 U.S. 367 (1988)

- ↑ Piette, Betsey (March 6, 2003). "Mumia still waiting for due process". International Concerned Family and Friends of Mumia Abu-Jamal. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Rimer, Sara (December 19, 2001). "Death sentence overturned in 1981 killing of officer". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Lindorff, Dave (December 8, 2005). "A victory for Mumia". Salon.com. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Duffy, Shannon P. (May 18, 2007). "Spectators Pack Courtroom as 3rd Circuit Hears Appeal in Mumia Abu-Jamal Case". The Legal Intelligencer. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Maurer-Carter, Terri (August 21, 2001). "Declaration of Terri Maurer-Carter". Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Conroy, Theresa (September 4, 2001). "She's 'scared' by impact of her allegation – Says Mumia judge made a racist remark". Philadelphia Daily News.

- ↑ "Sur Petition for Rehearing Abu-Jamal v. Horn et al." (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. July 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ↑ "''Jeffrey A. Beard, Secretary, Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, et al. v. Mumia Abu-Jamal, case no. 01-9014''". Supremecourt.gov. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ Lindorff, Dave (November 10, 2010). "Mumia: New Lawyer, New Round". Counterpunch.org. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ↑ Audio recording of oral arguments in Abu-Jamal v Beard before US 3rd Circuit Court of Appeal at Philadelphia on 9 November 2010.

- ↑ Williams, Timothy (Decembery 7, 2011). "Execution Case Dropped Against Abu-Jamal". New York Times. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ↑ Decision of Appeal upon Judgment of Sentence in Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v Mumia Abu-Jamal, Superior Court of Pennsylvania (July 9, 2013)

- ↑ 100 Yale L.J. 993 (1990–1991), "Teetering on the Brink: Between Death and Life"; Abu-Jamal, Mumia

- ↑ Carter, Kevin L (May 16, 1994). "A voice of Death Row to be heard on NPR". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Carter, Kevin L (May 17, 1994). "Inmate's broadcasts canceled". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Mumia Abu-Jamal Sues NPR, Claiming Censorship". Court TV. March 26, 1996. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Judge Dismisses Inmate's Suit Against NPR". The Washington Post. 22 August 1997.

- ↑ "Inmate's commentaries, dropped by NPR, will appear in print". The Philadelphia Inquirer. March 6, 1995. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Mumia Abu-Jamal to Speak at College Graduation Ceremonies" (Press release). Peter Bohmer of Evergreen State College, Washington. May 26, 1999. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Reynolds, Mark (June 2, 2004). "Whatever Happened to Mumia Abu-Jamal?". PopMatters. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Honorary Degrees". New College of California School of Law. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Abu-Jamal, Mumia. "Mumia Abu-Jamal's Radio Broadcasts – essay transcripts and archived mp3". PrisonRadio.org. Archived from the original on 2007-10-27. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (August 25, 1998). Opinion in Mumia Abu-Jamal v. James Price, Martin Horn, and Thomas Fulcomer, No. 96-3756 (txt). Villanova University School of Law. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Kummer, Frank (2012-01-29). "Abu-Jamal moved into general prison population for first time". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 2012-04-26.

- ↑ "San Francisco ILWU Local 10 Executive Board Resolution – Support for April 24, 1999 demonstrations in favor of the cause of Mumia Abu-Jamal (also describing support of other named labor union groups)" (Press release). ILWU. February 9, 1999. Archived from the original on 2009-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Service Employees International Union (SEIU) voted without dissent to demand justice for Mumia Abu-Jamal" (Press release). International Convention of the SEIU. 1999. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "Formal resolution "support(ing) a new, fair trial for activist Mumia Abu-Jamal"" (Press release). APWU. July 26, 2000. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Cynthia McKinney (June 19, 2009). "Mumia Abu-Jamal: Grave injustice". GlobalResearch.ca. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- ↑ Elijah, Jill Soffiyah (July 26, 2006). Brief of Amici Curiae National Lawyers Guild, National Conference of Black Lawyers, International Association of Democratic Lawyers et al. in support of Mumia Abu-Jamal in the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (PDF). National Lawyers Guild. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ "Educators for Mumia Abu-Jamal website". Educators for Mumia Abu-Jamal. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch (1996). United States 1996 country report – citing advocacy on behalf of Mumia Abu-Jamal to the Governor of Pennsylvania and the Superintendent of Waynesburg State Correctional Institution in 1995. From World Report 1996. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 107.3 Ceïbe, Cathy; Patrick Bolland (translator) (November 13, 2006). "USA Sues Paris: From Death Row, Mumia Stirs Up More Controversy". L'Humanité. Archived from the original on 2009-06-07. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 "59th Republican Ward Executive Committee Files Criminal Charges Against Cities of Paris and Suburb for 'Glorifying' Infamous Philadelphia Cop-Killer". 59th Republican Ward Executive Committee – City of Philadelphia. December 11, 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ "The Danny Faulkner Story – Related Information". Fraternal Order of Police. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "FOP attacks supporters of convicted cop killer" (Press release). Fraternal Order of Police. August 11, 1999. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ O'Connor, J. Patrick, The Framing of Mumia Abu-Jamal, page 199

- ↑ "Chief page for the prize at the Web site of the Erich Mühsam Society (in German)". Erich-muehsam-gesellschaft.de. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ "With United Power Forward" (in German). junge Welt. October 7, 2002. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ "Annual Report on the Protection of the Constitution 2005". Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution. 2006. p. 168. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- ↑ Simons, Stefan (June 29, 2006). "Paris Street for Mumia Abu-Jamal Sparks Trans-Atlantic Row". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "HR 407, 109th US Congress". GovTrack.us. May 19, 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "SR 102, 109th US Congress". GovTrack.us. June 15, 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ "HR 1082, 109th US Congress". GovTrack.us. December 6, 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ Celizic, Mike (December 6, 2007). "Officer's widow speaks out on Mumia case". Today. MSNBC. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ Faulkner, Maureen; Smerconish, Michael A. (2007). Murdered by Mumia: A Life Sentence of Loss, Pain, and Injustice. Lyons Press. ISBN 1-59921-376-1.

- ↑ Review in Independent Publishers Group of The Framing of Mumia Abu-Jamal May, 2008.

- ↑ Wickham Jr, Henry P. (May 17, 2008). "Mumia Abu-Jamal: Still Guilty!". American Thinker.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mumia Abu-Jamal. |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Mumia Abu-Jamal |

Video

- 1996 video of death row visitation interview with Mumia Abu-Jamal

- Competing Films Offer Differing Views – video report by Democracy Now!

Supporter groups

- Free Mumia Abu-Jamal Coalition (New York City)

- Partisan Defense Committee

- Journalists for Mumia

- Educators for Mumia Abu-Jamal

Opponent groups

- Summary of the prosecution's case

- Fraternal Order of Police news, press releases, and communications relating to Mumia Abu-Jamal

- Justice For Daniel Faulkner

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|