Mount Rushmore

| Mount Rushmore National Memorial | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

-3_new.jpg) Sculptures of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln (left to right) represent the first 130 years of the history of the United States. | |

| |

| Location | Pennington County, South Dakota, United States |

| Nearest city | Keystone, South Dakota |

| Coordinates | 43°52′44.21″N 103°27′35.37″W / 43.8789472°N 103.4598250°WCoordinates: 43°52′44.21″N 103°27′35.37″W / 43.8789472°N 103.4598250°W |

| Area | 1,278.45 acres (5.17 km2) |

| Established | March 3, 1925 |

| Visitors | 2,185,447 (in 2012)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

The Mount Rushmore National Memorial is a sculpture carved into the granite face of Mount Rushmore (Lakota Sioux name: Six Grandfathers) near Keystone, South Dakota, in the United States. Sculpted by Danish-American Gutzon Borglum and his son, Lincoln Borglum, Mount Rushmore features 60-foot (18 m) sculptures of the heads of four United States presidents: George Washington (1732–1799), Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) and Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865).[4] The entire memorial covers 1,278.45 acres (5.17 km2)[5] and is 5,725 feet (1,745 m) above sea level.[6]

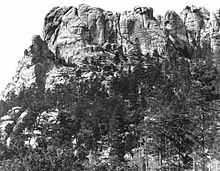

South Dakota historian Doane Robinson is credited with conceiving the idea of carving the likenesses of famous people into the Black Hills region of South Dakota in order to promote tourism in the region. Robinson's initial idea was to sculpt the Needles; however, Gutzon Borglum rejected the Needles site because of the poor quality of the granite and strong opposition from Native American groups. They settled on the Mount Rushmore location, which also has the advantage of facing southeast for maximum sun exposure. Robinson wanted it to feature western heroes like Lewis and Clark, Red Cloud,[7] and Buffalo Bill Cody,[8] but Borglum decided the sculpture should have a more national focus and chose the four presidents whose likenesses would be carved into the mountain. After securing federal funding through the enthusiastic sponsorship of "Mount Rushmore's great political patron," U.S. Senator Peter Norbeck,[9] construction on the memorial began in 1927, and the presidents' faces were completed between 1934 and 1939. Upon Gutzon Borglum's death in March 1941, his son Lincoln Borglum took over construction. Although the initial concept called for each president to be depicted from head to waist, lack of funding forced construction to end in late October 1941.

Mount Rushmore has become an iconic symbol of presidential greatness and has appeared in works of fiction, and has been discussed or depicted in other popular works. It attracts nearly three million people annually.[10]

History

Originally known to the Lakota Sioux as Six Grandfathers, the mountain was renamed after Charles E. Rushmore, a prominent New York lawyer, during an expedition in 1885.[11] At first, the project of carving Rushmore was undertaken to increase tourism in the Black Hills region of South Dakota. After long negotiations involving a Congressional delegation and President Calvin Coolidge, the project received Congressional approval. The carving started in 1927, and ended in 1941 with no fatalities.[12]

As Six Grandfathers, the mountain was part of the route that Lakota leader Black Elk took in a spiritual journey that culminated at Harney Peak. Following a series of military campaigns from 1876 to 1878, the United States asserted control over the area, a claim that is still disputed on the basis of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie (see section "Controversy" below). Among American settlers, the peak was known variously as Cougar Mountain, Sugarloaf Mountain, Slaughterhouse Mountain, and Keystone Cliffs. It was named Mount Rushmore during a prospecting expedition by Charles Rushmore, David Swanzey (husband of Carrie Ingalls), and Bill Challis.[13]

Historian Doane Robinson conceived the idea for Mount Rushmore in 1923 to promote tourism in South Dakota. In 1924, Robinson persuaded sculptor Gutzon Borglum to travel to the Black Hills region to ensure the carving could be accomplished. Borglum had been involved in sculpting the Confederate Memorial Carving, a massive bas-relief memorial to Confederate leaders on Stone Mountain in Georgia, but was in disagreement with the officials there.[14] The original plan was to perform the carvings in granite pillars known as the Needles. However, Borglum realized that the eroded Needles were too thin to support sculpting. He chose Mount Rushmore, a grander location, partly because it faced southeast and enjoyed maximum exposure to the sun. Borglum said upon seeing Mount Rushmore, "America will march along that skyline."[15] Congress authorized the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission on March 3, 1925.[15] President Coolidge insisted that, along with Washington, two Republicans and one Democrat be portrayed.[16]

Between October 4, 1927, and October 31, 1941, Gutzon Borglum and 400 workers[17] sculpted the colossal 60 foot (18 m) high carvings of U.S. presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln to represent the first 130 years of American history. These presidents were selected by Borglum because of their role in preserving the Republic and expanding its territory.[15][18] The image of Thomas Jefferson was originally intended to appear in the area at Washington's right, but after the work there was begun, the rock was found to be unsuitable, so the work on the Jefferson figure was dynamited, and a new figure was sculpted to Washington's left.[15]

In 1933, the National Park Service took Mount Rushmore under its jurisdiction. Julian Spotts helped with the project by improving its infrastructure. For example, he had the tram upgraded so it could reach the top of Mount Rushmore for the ease of workers. By July 4, 1934, Washington's face had been completed and was dedicated. The face of Thomas Jefferson was dedicated in 1936, and the face of Abraham Lincoln was dedicated on September 17, 1937. In 1937, a bill was introduced in Congress to add the head of civil-rights leader Susan B. Anthony, but a rider was passed on an appropriations bill requiring federal funds be used to finish only those heads that had already been started at that time.[19] In 1939, the face of Theodore Roosevelt was dedicated.

The Sculptor's Studio — a display of unique plaster models and tools related to the sculpting — was built in 1939 under the direction of Borglum. Borglum died from an embolism in March 1941. His son, Lincoln Borglum, continued the project. Originally, it was planned that the figures would be carved from head to waist,[20] but insufficient funding forced the carving to end. Borglum had also planned a massive panel in the shape of the Louisiana Purchase commemorating in eight-foot-tall gilded letters the Declaration of Independence, U.S. Constitution, Louisiana Purchase, and seven other territorial acquisitions from Alaska to Texas to the Panama Canal Zone.[18]

The entire project cost US$989,992.32.[21] Notable for a project of such size, no workers died during the carving.[22]

On October 15, 1966, Mount Rushmore was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A 500-word essay giving the history of the United States by Nebraska student William Andrew Burkett was selected as the college-age group winner in a 1934 competition, and that essay was placed on the Entablature on a bronze plate in 1973.[19] In 1991, President George H. W. Bush officially dedicated Mount Rushmore.[23]

In a canyon behind the carved faces is a chamber, cut only 70 feet (21 m) into the rock, containing a vault with sixteen porcelain enamel panels. The panels include the text of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, biographies of the four presidents and Borglum, and the history of the U.S. The chamber was created as the entrance-way to a planned "Hall of Records"; the vault was installed in 1998.[24]

Ten years of redevelopment work culminated with the completion of extensive visitor facilities and sidewalks in 1998, such as a Visitor Center, the Lincoln Borglum Museum, and the Presidential Trail. Maintenance of the memorial requires mountain climbers to monitor and seal cracks annually. Due to budget constraints, the memorial is not regularly cleaned to remove lichens. However, on July 8, 2005, Alfred Kärcher GmbH, a German manufacturer of pressure washing and steam cleaning machines, conducted a free cleanup operation which lasted several weeks, using pressurized water at over 200 °F (93 °C).[25]

Ecology

The flora and fauna of Mount Rushmore are similar to those of the rest of the Black Hills region of South Dakota. Birds including the turkey vulture, bald eagle, hawk, and meadowlark fly around Mount Rushmore, occasionally making nesting spots in the ledges of the mountain. Smaller birds, including songbirds, nuthatches, and woodpeckers, inhabit the surrounding pine forests.[26] Terrestrial mammals include the mouse, least chipmunk, red squirrel, skunk, porcupine, raccoon, beaver, badger, coyote, bighorn sheep, bobcat, elk, mule deer, yellow-bellied marmot, and American bison.[26][27] The striped chorus frog, western chorus frog, and northern leopard frog also inhabit the area.[28] In addition, several species of snakes inhabit the region. Grizzly Bear Brook and Starling Basin Brook, the two streams in the memorial, support fish such as the longnose dace and the brook trout.[citation needed] Mountain goats are not indigenous to the area but can also be found here. They are descended from goats which were a gift from Canada to Custer State Park in 1924 but later escaped.[26][29][30]

At lower elevations, coniferous trees, mainly the Ponderosa pine, surround most of the monument, providing shade from the sun. Other trees include the bur oak, the Black Hills spruce, and the cottonwood. Nine species of shrubs grow near Mount Rushmore. There is also a wide variety of wildflowers, including especially the snapdragon, sunflower, and violet. Towards higher elevations, plant life becomes sparser.[30] However, only approximately five percent of the plant species found in the Black Hills are indigenous to the region.[31]

The area receives about 18 inches (460 mm) of precipitation on average per year, enough to support abundant animal and plant life. Trees and other plants help to control surface runoff. Dikes, seeps, and springs help to dam up water that is flowing downhill, providing watering spots for animals. In addition, stones like sandstone and limestone help to hold groundwater, creating aquifers.[32]

Through the study of tree rings, it has been determined that forest fires have occurred in the Ponderosa forests surrounding Mount Rushmore around every 27 years based on evidence of fire scars found within tree core samples. Large conflagrations are not common. Most events have been ground fires that serve to clear forest debris.[33] The area is a climax community. Recent pine beetle infestations have threatened the forest.[27]

Geography

Climate

Mount Rushmore is inside a USDA Plant Hardiness Zone of 5a, meaning certain plant life in the area can withstand a low temperature of no more than −20 °F (−29 °C).[34]

The two wettest months of the year are May and June. Orographic lift causes brief but strong afternoon thunderstorms during the summer.[35]

| Climate data for Mount Rushmore National Memorial, 1981-2011 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

68 (20) |

78 (26) |

85 (29) |

93 (34) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

99 (37) |

97 (36) |

86 (30) |

75 (24) |

67 (19) |

100 (38) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 36 (2) |

37 (3) |

43 (6) |

51 (11) |

61 (16) |

71 (22) |

79 (26) |

78 (26) |

68 (20) |

55 (13) |

43 (6) |

35 (2) |

54.8 (12.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 28 (−2) |

28 (−2) |

34 (1) |

42 (6) |

52 (11) |

61 (16) |

69 (21) |

68 (20) |

58 (14) |

46 (8) |

35 (2) |

27 (−3) |

45.7 (7.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 19 (−7) |

19 (−7) |

25 (−4) |

32 (0) |

42 (6) |

51 (11) |

59 (15) |

58 (14) |

48 (9) |

37 (3) |

26 (−3) |

18 (−8) |

36.2 (2.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −38 (−39) |

−29 (−34) |

−12 (−24) |

1 (−17) |

14 (−10) |

27 (−3) |

35 (2) |

33 (1) |

19 (−7) |

1 (−17) |

−12 (−24) |

−31 (−35) |

−38 (−39) |

| Precipitation inches (mm) | 0.38 (9.7) |

0.70 (17.8) |

1.19 (30.2) |

2.23 (56.6) |

4.22 (107.2) |

3.41 (86.6) |

2.90 (73.7) |

1.99 (50.5) |

1.81 (46) |

1.68 (42.7) |

0.62 (15.7) |

0.43 (10.9) |

21.56 (547.6) |

| Snowfall inches (cm) | 5.8 (14.7) |

7.9 (20.1) |

10.4 (26.4) |

10.8 (27.4) |

1.2 (3) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

3.6 (9.1) |

6.2 (15.7) |

5.8 (14.7) |

52.4 (132.9) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.01) | 4.3 | 4.7 | 6.3 | 8.2 | 11.9 | 12.6 | 11.4 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 91.5 |

| Avg. snowy days (≥ 0.1) | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 23.1 |

| Source #1: [36] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: [37] | |||||||||||||

Geology

Mount Rushmore is largely composed of granite. The memorial is carved on the northwest margin of the Harney Peak granite batholith in the Black Hills of South Dakota, so the geologic formations of the heart of the Black Hills region are also evident at Mount Rushmore. The batholith magma intruded into the pre-existing mica schist rocks during the Proterozoic, roughly 1.6 billion years ago.[38] Coarse grained pegmatite dikes are associated with the granite intrusion of Harney Peak and are visibly lighter in color, thus explaining the light-colored streaks on the foreheads of the presidents.

The Black Hills granites were exposed to erosion during the Neoproterozoic, but were later buried by sandstone and other sediments during the Cambrian. Remaining buried throughout the Paleozoic, they were re-exposed again during the Laramide orogeny around 70 million years ago.[38] The Black Hills area was uplifted as an elongated geologic dome.[39] Subsequent erosion stripped the granite of the overlying sediments and the softer adjacent schist. Some schist does remain and can be seen as the darker material just below the sculpture of Washington.

The tallest mountain in the region is Harney Peak (7,242 ft or 2,207 m). Borglum selected Mount Rushmore as the site for several reasons. The rock of the mountain is composed of smooth, fine-grained granite. The durable granite erodes only 1 inch (25 mm) every 10,000 years, thus was more than sturdy enough to support the sculpture and its long-term exposure.[15] The mountain's height of 5,725 feet (1,745 m) above sea level[6] made it suitable, and because it faces the southeast, the workers also had the advantage of sunlight for most of the day.

Conservation

The ongoing conservation of the site is overseen by the US National Park Service.[40] Physical efforts to conserve the monument have included replacement of the sealant applied originally by Gutzon Borglum, which had proved ineffective at providing water resistance (components include linseed oil, granite dust and white lead). A modern silicone replacement was used, disguised with granite dust.

In 1998, electronic monitoring devices were installed to track movement in the topology of the sculpture to an accuracy of 3 mm. The site has been subsequently digitally recorded using a terrestrial laser scanning methodology in 2009 as part of the international Scottish Ten project, providing a record of unprecedented resolution and accuracy to inform the conservation of the site. This data was made accessible online to be freely used by the wider community to aid further interpretation and public access.[41]

Tourism

Tourism is South Dakota's second-largest industry, and Mount Rushmore is the state's top tourist attraction.[12] The memorial hosts nearly three million visitors a year.[10] In 2012, 2,185,447 people visited the park.[3] The site attracts many visitors over the week of the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally.[citation needed]

Controversy

Mount Rushmore is controversial among Native Americans because the United States seized the area from the Lakota tribe after the Great Sioux War of 1876. The Treaty of Fort Laramie from 1868 had previously granted the Black Hills to the Lakota in perpetuity. Members of the American Indian Movement led an occupation of the monument in 1971, naming it "Mount Crazy Horse". Among the participants were young activists, grandparents, children and Lakota holy man John Fire Lame Deer, who planted a prayer staff atop the mountain. Lame Deer said the staff formed a symbolic shroud over the presidents' faces "which shall remain dirty until the treaties concerning the Black Hills are fulfilled."[42]

In 2004, the first Native American superintendent of the park was appointed. Gerard Baker has stated that he will open up more "avenues of interpretation", and that the four presidents are "only one avenue and only one focus."[43]

The Crazy Horse Memorial is being constructed elsewhere in the Black Hills to commemorate the famous Native American leader and as a response to Mount Rushmore. It is intended to be larger than Mount Rushmore and has the support of Lakota chiefs; the Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation has rejected offers of federal funds. However, this memorial is likewise the subject of controversy, even within the Native American community.[44]

The monument also provokes controversy because some allege that underlying it is the theme of racial superiority legitimized by the idea of Manifest Destiny. The four presidents chosen by Borglum were all active during the period when the United States was annexing Native American land. Gutzon Borglum himself excites controversy, because he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.[14][45]

In May 2012 James Anaya, a United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, conducted the United Nations’ first-ever investigation into the plight of Native Americans living in the United States. Anaya’s recommendations include advising the U.S. to return some land to Native American tribes, including South Dakota’s Black Hills.[46]

In popular culture

.jpg)

Because of its fame as a monument, Mount Rushmore is frequently discussed or depicted in media, film and popular culture. The memorial was iconically used as the location of the climactic chase scene in Alfred Hitchcock's 1959 movie North by Northwest. Scriptwriter Ernest Lehman recalled that in the course of screenwriting, Hitchcock "murmured wistfully, 'I always wanted to do a chase across the faces of Mount Rushmore.'"[47] The scene was not actually filmed at the monument, since permission to shoot an attempted killing on the face of a national monument was refused by the National Park Service. In the movie, the villain's house is located on a fictitious forested plateau behind the monument.[48]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ "Honeycombing process explained from". nps.gov. June 14, 2004. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Geology Fieldnotes". nps.gov. January 4, 2005. Retrieved Oct 22, 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Park Statistics". National Park Service. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Mount Rushmore National Memorial. December 6, 2005.60 SD Web Traveler, Inc. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ↑ McGeveran, William A. Jr. et al. (2004). The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2004. New York: World Almanac Education Group, Inc. ISBN 0-88687-910-8.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mount Rushmore, South Dakota (November 1, 2004). Peakbagger.com. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- ↑ Penn & Teller: Bullshit!, episode 5x08 "Mount Rushmore", May 10, 2007

- ↑ "Making Mount Rushmore | Mount Rushmore". Oh, Ranger!. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ↑ "Biography:Senator Peter Norbeck". American Experience: Mount Rushmore. PBS. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Mount Rushmore Park Home". National Park Service. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ↑ Belanger, Ian A. et al. "Mt. Rushmore — presidents on the rocks" at the Wayback Machine (archived May 14, 2006)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Mount Rushmore National Memorial Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ↑ Keystone Area Historical Society Keystone Characters. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "People & Events: The Carving of Stone Mountain". American Experience. PBS. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Carving History (October 2, 2004). National Park Service.

- ↑ Fite, Gilbert C. Mount Rushmore (May 2003). ISBN 0-9646798-5-X, the standard scholarly study.

- ↑ "Carving History". National Park Service. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Albert Boime, "Patriarchy Fixed in Stone: Gutzon Borglum's 'Mount Rushmore'," American Art, Vol. 5, No. 1/2. (Winter – Spring, 1991), pp. 142–67.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 American Experience "Timeline: Mount Rushmore" (2002). Retrieved March 20, 2006.

- ↑ Mount Rushmore National Memorial.

- ↑ Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Tourism in South Dakota. Laura R. Ahmann. Retrieved March 19, 2006.

- ↑ Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Outdoorplaces.com. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- ↑ "George Bush: Remarks at the Dedication Ceremony of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota". The American Presidency Project. July 3, 1991. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Hall of Records". Mount Rushmore National Memorial web site. National Park Service. June 14, 2004. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ↑ "For Mount Rushmore, An Overdue Face Wash". Washington Post. July 11, 2005. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "Enjoy Wildlife......Safely.". National Park Service. National Park Service. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Freeman, Mary. "Mount Rushmore, South Dakota for Tourists". USA Today (Tysons Corner, VA: Gannett Company). Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Amphibians". National Park Service. National Park Service. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Nature & Science- Animals". NPS. November 26, 2006. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Mount Rushmore- Flora and Fauna. American Park Network. URL accessed on March 16, 2006. Web archive link Archived March 17, 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Nature & Science – Plants". NPS. December 6, 2006. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ Nature & Science- Groundwater. National Park Service. Retrieved April 1, 2006.

- ↑ Nature & Science- Forests. National Park Service. Retrieved April 1, 2006.

- ↑ "USDA Hardiness Zone Finder". The National Gardening Association. National Gardening Association. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Weather History". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. June 23, 2004. Archived from the original on July 8, 2006. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for Mount Rushmore Natl Memorial, SD". The Weather Channel. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Geologic Activity. National Park Service.

- ↑ Irvin, James R. Great Plains Gallery (2001). Retrieved March 16, 2006.

- ↑ "Caring For A Monumental Sculpture". National Park Service. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Mount Rushmore National Memorial". CyArk. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Matthew Glass, "Producing Patriotic Inspiration at Mount Rushmore," Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 62, No. 2. (Summer, 1994), pp. 265–283.

- ↑ David Melmer (December 13, 2004). "Historic changes for Mount Rushmore". Indiancountrytoday. Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ Lame Deer, John (Fire) and Richard Erdoes. Lame Deer Seeker of Visions. Simon and Schuster, New York, New York, 1972. Paperback ISBN 0-671-55392-5

- ↑ "Gutzon Borglum, The Story of Mount Rushmore". Ralphmag.org. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ "UN Probe: U.S. Should Return Stolen Sacred Land, Including Mt. Rushmore, to Native Americans". Democracy Now!. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ↑ Barbara Straumann, "Rewriting American Foundational Myths in Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest", in Martin Heusser and Gudrun Grabher, American Foundational Myths (2002), p. 201.

- ↑ North by Northwest: Hitchcock’s House on Mt. Rushmore. Hookedonhouses.net. Retrieved on 2011-10-06.

Further reading

- Larner, Jesse. Mount Rushmore: An Icon Reconsidered New York: Nation Books, 2002.

- Taliaferro, John. Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mount Rushmore. New York: PublicAffairs, c2002. ISBN 9781586482053. Puts the creation of the monument into a historical and cultural context.

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: United States Department of the Interior

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mount Rushmore National Memorial. |

- Official website

- "Making Mount Rushmore". Oh, Ranger!. APN Media. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- Dobrzynski, Judith H. (July 15, 2006). "A Monumental Achievement". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- Buckingham, Matthew (Summer 2002). "The Six Grandfathers, Paha Sapa, in the Year 502,002 C.E.". Cabinet Magazine. Immaterial Incorporated. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- "Luigi Del Bianco: chief stone carver on Mount Rushmore, 1933–1940". Lou Del Bianco. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- "Caring For A Monumental Sculpture". National Park Service. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||